By Joseph R. Svinth

Copyright © Joseph R. Svinth 2001. All rights reserved.

The assistance of Andrew Dale, Aaron Fields, Kregg P.J. Jorgenson, Bernie Lau, Renee Mulier Lau, Curtis Narimatsu, Doug Walker, and Neil Yamamoto is gratefully acknowledged.

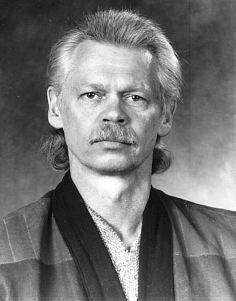

In 1955, at the age of 14, Bernie Lau began training in aikido under Koichi Tohei. During the 1960s, Lau was a pioneer aikido instructor in Seattle, and during the 1970s and 1980s, he helped develop aikido-based police defensive tactics. A retired undercover detective, he continues to teach seminars and his nephew.

Bernie Lau, June 1996

Bernard Mulier was born in Lille, France, on June 8, 1941. His mother was not married to his father, and so to avoid scandal he was sent to the country to be raised by relatives. He remembers growing up in a two-story brick house, and spending a lot of time in the cellar during Allied air raids. It was dark down there, and what little light there was glittered on the luminescent trails left by slugs. The food was monotonous, too: rabbit, bread spread with a little lard, and wine mixed with water. But it was wartime, and that was the way the world was.

In 1947, his mother, Renee Mulier, received a letter from a US Air Force lieutenant she had met during the war; he wanted to know if she would marry him. She said yes, so off they went to America, a picture bride and her son. Bernie remembers crossing the English Channel because he was sick the whole time. Mother and son met the former airman, Reginald Karn Fong Lau, in New York. Because he was Chinese and they were white, they had to stay in a third-class hotel because no first-class hotel would accept mixed-race couples. [EN1]

From New York they traveled to Hilo, Hawaii, where Reginald Lau’s family ran a store called Hilo Dry Goods. In Hawaii, Bernie attended Riverside Elementary, Hilo Intermediate, and Hilo High School. He says he didn’t wear shoes to school until junior high; in those days, most kids didn’t, probably because it rains a lot in Hilo and kids like puddles.

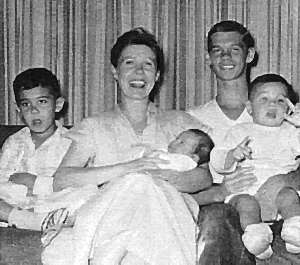

Lau with his mother, Renee, and her other three children, Craig, Mark, and Lance.

To Reginald Lau’s disgust, Bernie never got good grades. He did so poorly, in fact, that he had to repeat third grade and he says he owes graduation in 1960 to a tsunami causing finals to be cancelled. Part of this he attributes to having been a natural left-hander converted to a right-hander (being left-handed wasn’t acceptable back then), but as an adult, he also discovered that he had an attention deficit disorder. Truth be told, he always preferred taking hikes to Rainbow Falls to sitting in classrooms.

Lau began his study of aikido in 1955, at age 14. One day he was walking along the beach at Hapuna when he saw a group of people practicing martial arts. What they were doing looked interesting, so he stopped to watch. A man noticed him and said, "Here, try and punch me." So Lau tried and something weird happened: he couldn’t hit the man. Now that Lau knows how the tricks are done, what the man did was nothing miraculous, but then it seemed like magic. Anyway, the magical man was aikido teacher Koichi Tohei, and with his father’s approval (discipline was good for a boy), Lau signed up for lessons immediately after.

Lau and Tohei, 1955.

Tohei was from Japan, and this was his second visit to Hawaii. Highly graded in both judo and aikido, he had established an aikido club in Hilo in 1953. The local instructor was Kiyoshi Nagata, and his assistants included Takashi Nonaka, a former kendoka who still heads the Hilo Ki-Aikido Club today. They were really nice men, says Lau, and liked by his parents, too. (His mother knew Nonaka well, as he delivered orchids to the place where she worked.)

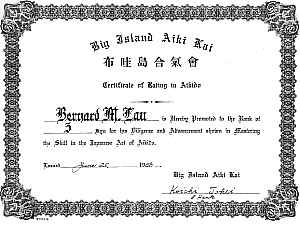

There were very few white kids in the Hilo aikido class. Michael Frenz was one of them, and another was a fellow who had done karate on Oahu, probably with Bobby Lowe. Lau’s first grading came on June 25, 1958. The grade awarded was 3-kyu, and the signature is that of Koichi Tohei, 8-dan.

"Big Island Aiki Kai. Certificate of Rating in Aikido. Bernard M. Lau is Hereby Promoted to the Rank of 3 Kyu for his Diligence and Advancement shown in Mastering the Skill in the Japanese Art of Aikido. Issued June 25, 1958. Big Island Aiki Kai, Koichi Tohei, 8 Rank."

During 1957 and 1958, Lau accompanied Tohei on his travels throughout Hawaii. They went to Honolulu, Maui; all over, really. Today he thinks people probably wondered about the teenaged white kid in the middle of all these adult Japanese and Japanese Americans. But anyway, he got to go, in part because his parents knew Nonaka, and so knew that he’d be watched after.

During these travels, Lau got to meet men that later became leaders of Hawaiian aikido. Despite all the talk about how aikido built character, when their wives weren’t around some of these men drank like fish and chased anything in skirts. Indeed, one aikido teacher who worked on a police vice squad went so far as to arrange hookers for the visitors. Several of the older men who didn’t go for such things took Lau elsewhere during these parties, but the hypocrisy was an eye-opener for the teenager from Hilo. "A lot of the time aikido isn’t the ‘Way of Harmony’," says Lau, "but the ‘Way of Disharmony.’ Club leaders used to do things like changing the locks on a member they didn’t like. That was how the guy found out he wasn’t welcome to train there any more. It wasn’t even as polite as ‘my way or the highway.’"

After graduating from high school, Lau enlisted in the US Navy. (It was either that or continue working at Hilo Dry Goods for 75¢ an hour.) He chose the Navy rather than some other service because he had a list of things he wanted to do with his life: he wanted to go to Japan, he wanted to be a submariner and a diver, and he wanted to be a policeman. "I remember writing that down on a piece of paper," he says. "Plain as day, that’s what I wrote down because I’d heard that there was power in writing down plans."

Unlike most people who write down plans, he then set about achieving them.

Following naval recruit training in San Diego, Lau trained as an electrician. Partially colorblind, he was unable to distinguish the differences between the colored spots on the eye charts. However, he could distinguish the colors on the yarn used in another color acuity test, and so he passed the course and ended up assigned to the Gato-class submarine USS Bluegill, SSK-242, for four years. After that, he re-enlisted to be a hard-hat diver, and he did that for another four years.

Seaman Lau, circa 1960.

At sea, he didn’t do much aikido because there wasn’t room for that sort of thing on World War II diesel submarines. But the Bluegill was assigned to Pearl Harbor, and of course there were aikido dojo in Honolulu.

The head instructor at the Hawaii Aiki Kai in Honolulu was Yukiso Yamamoto. An Issei who came to Hawaii in 1923, Yamamoto enjoyed hurting haoles. As a result, there weren’t many white people in his classes. However, being from Hilo and having traveled with Tohei, Lau didn’t really count as a haole. Furthermore, he had friends at the Hawaii Aiki Kai, and of course that helped, too. One of these friends was Meyer Goo, who had helped pioneer aikido in New York a few years before, and another was Alex Tripp.

Yukiso Yamamoto, early 1960s.

Yamamoto’s aikido wasn’t the touchy-feely stuff often seen today. Instead it was more like jujutsu, which isn’t surprising since Yamamoto was ranked 5-dan in judo before he met Tohei and switched to aikido. Thus there was lots of sweaty hard work, and very little talk about the magical powers of ki (intrinsic energy).

Meyer Goo, mid-1960s.

Once a month, on a Sunday, Lau attended a misogi, or discipline session, in which members did things such as sit under waterfalls. Although Ueshiba and Tohei practiced misogi for religious reasons, Lau did it mostly because it was "kind of neat, kind of exotic, you know?" They’d walk half an hour through the trees to Manoa Falls, train a bit, and then walk back to their cars where they’d drink coffee and eat doughnuts, which really tasted good when you were so cold.

The two times that his ship was in Japan, Lau trained at the Aikikai Hombu in Tokyo. One visit was for a couple weeks in 1962 while the other was for a similar period during late 1963 or early 1964. During the second visit Lau met Morihei Ueshiba,

Although he rarely assisted with instruction, Ueshiba was often in the dojo. He always had a twinkle in his eye, and he was funny to watch, too, as he was the only person Lau knew who practiced aikido while wearing long johns under his keikogi (practice clothes). Lau had a bottle of whisky that Yukiso Yamamoto had given him to deliver to Ueshiba, so when Ueshiba made his appearance at the dojo, Lau got out the bottle out and gave it to him. Ueshiba liked that, so Lau figured what the heck and brought out some pictures for Ueshiba to sign, too. The hangers-on around Ueshiba were appalled that some gaijin would simply walk up to The Founder and ask him to sign a photograph, but Ueshiba just beamed, and happily signed away. Lau also has Ueshiba’s autograph on his 1-dan and 2-dan certificates. Interestingly, the first certificate, issued in 1962, is in the old-fashioned trifold style.

The foreign student that Lau best remembers from his visits to the Aikikai Hombu is Virginia Mayhew. Mayhew was one of the first American women to study aikido in Japan, and later she was the first woman to teach aikido in Hong Kong. Her married name was Bailey, and today she lives in San Francisco. Lau remembers Mayhew fondly because she invited him to her house, and then fed him toast, coffee, and eggs. That may not sound very special, but in those days, it was almost impossible to get toast, coffee, and eggs in Tokyo. She also told riotous stories heard in the Women’s Section, ribald tales about famous masters whose ki did not extend nearly as well on the futon as on the tatami.

Following his discharge from the Navy in 1968, Lau moved to Seattle, where he took a job working as a policeman for the University of Washington. While there, he started a university-based aikido club that was affiliated with the Hawaii Aiki Kai. This made him the first yudansha to teach aikido in Seattle. (Tom Katsuyoshi started teaching aikido in Seattle in 1967, but at the time Katsuyoshi was only ranked ikkyu, or first brown. Katsuyoshi’s early students included John Kanetomi, Nat Steiger, and Doug Tsuboi. The next yudansha to teach aikido in Seattle was Yoshihiko Hirata, a Tohei-trained 4-dan who started a club in late 1969.) [EN2]

In 1970 Lau accepted a better-paying job with the Seattle Police Department. Since this meant he no longer had free access to the University of Washington gym, he began teaching at the Washington Karate Association dojo located at 85th and 15th. However, Washington Karate Association owner Julius Thiry hadn’t mentioned that he was locking students in using long-term contracts that they couldn’t get out of, and when he discovered that, then Lau was out of there. So that his students could leave, too, Lau bought their contracts from Thiry. Contracts may be good business, says Lau, but they aren’t good budo.

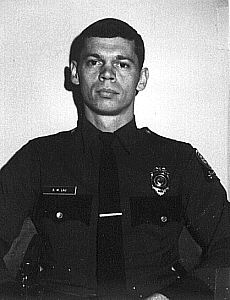

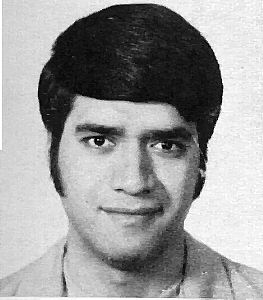

Seattle Police Officer Bernie Lau, 1970.

Lau resumed teaching aikido at the Seattle Buddhist Temple, at 1427 South Main. John Kanetomi and Doug Tsuboi were also teaching aikido, first at the Jefferson Park community center and then at the Washington Budokan, which was then at 301 Main Street. It was at the latter location that Lau, who was then unaffiliated, first met Yoshihiko Hirata.

Hirata was from Japan, and although he was ranked 4-dan in aikido, he made his living as a violin teacher. He had trained directly under Tohei, and so when Tohei visited the US in 1973, he made a trip to Seattle to see Hirata. The visit was in June, and demonstration sites included the Queen Anne Community Center and the University of Washington. Many people think that aikido’s philosophy is inherent in the techniques. While true in an absolute sense, no one teaches well enough, is skilled enough, or lives by the philosophy so well that he or she can convey the meaning behind the technical skill solely through hands-on experience. Recognizing this, important parts of Tohei’s instruction took place during discussions in the restaurant after class. During these discussions, Tohei would drink anything anyone put in front of him. One evening, Hirata tried keeping up, drink for drink, and the next morning he arrived for training in horrible condition. Tohei walked in clear eyed, fresh shaven and showered. He took one look at Hirata and said, "If you can’t handle your alcohol, you should not drink."

Shortly after Tohei’s visit, Lau began cross-training in Goju Kai karate. His instructors included Bill Reuter and Dick Daley. He decided to train with them based on their performance during the Goju Kai Internationals held in Seattle in 1973: Reuter’s wife Judy had dominated the women’s division while Daley took third place in men’s black belt fighting, which was the highest placement of any non-Japanese male. And besides, Reuter was from Hawaii, too.

Bill Reuter, early 1970s.

Lau’s interest in karate was sparked by two separate incidents in which properly applied aikido joint locks failed to subdue the people he was trying to arrest. "I tried traditional aikido techniques," he says, "and they simply pulled out of them. We’re talking big guys who knew how to street fight." He himself did not get hurt as a result, but both suspects and a partner did. This bothered him. "I felt that if I could have better controlled the situation, then things might have turned out differently." When he mentioned the problem to Sadao Yoshioka, a former aikido instructor from Honolulu, Yoshioka replied that strikes could provide openings for locking techniques that were otherwise impossible to obtain. "But there are no strikes in aikido," protested Lau. "True," replied Yoshioka, "but that is because Ueshiba was working on spiritual development rather than fighting, and so he took them out. Look at old photos and you’ll see what I mean."

So Lau began collecting old photos. This led him to an exchange of letters and ideas with the San Diego-based martial arts instructor Fred Lovret. During the mid-1960s, Meyer Goo had mentioned a turn-of-the-century Japanese martial art teacher named Sokaku Takeda, who was whispered to have been a teacher of Morihei Ueshiba. The Aikikai downplayed this story, but it was persistent. So when Lovret said, "Oh yes, that story is true," and then gave Lau an address for Takeda’s son Tokimune, Lau immediately wrote Takeda a letter. And, via the sneaky policeman’s trick of including a $50 bill in the envelope, he even got a detailed, helpful, response.

His research also led him to Don Angier, an aikijujutsu instructor from Long Beach, California, and to aikido researcher and journalist Stan Pranin. In 1985, Pranin met with Tokimune Takeda in Hokkaido, and there became convinced that there was a connection between aikido and Daito-ryu aikijujutsu. A few years later, Pranin spent several days visiting Lau at his house. After looking at Lau’s pictures of Sokaku Takeda and other turn-of-the-century aikijujutsu practitioners, Pranin said, "Can I get copies of these?" As a result, many of Lau’s pictures have appeared in Aikido Journal over the years.

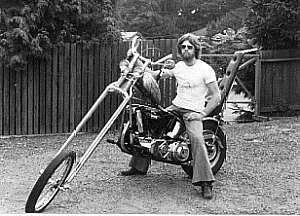

Bernie Lau, spring 1975. "I owned that bike only a couple weeks

before I fell and broke my leg," he says. "So for the next few months I

was doing drug buys as a biker who broke his leg on his motorcycle.

Everybody

understood that story; it worked real well."

Unfortunately, the Seattle aikido community was not doing so nicely. Yoshihiko Hirata was a proud, almost arrogant, man, and his attitude alienated many people. So, when he decided to affiliate with Tohei’s Ki no Kenyukai organization in 1974, Lau and many others, to include Andy Dale, John Kanetomi, Chuck Livingston, Nat Steiger, and Doug Tsuboi, decided to stay with the Aikikai. Since the name "Washington Aikikai" belonged to Kanetomi and Steiger, this forced Hirata to reorganize his club, which he did using the name Seattle Ki Society. Meanwhile, since Hirata owned the lease to the dojo, the Washington Aikikai was forced to look for new training space, which ended up being inside the Seattle judo club known as the Seattle Dojo.

Shortly after all unpleasantness settled itself out, Lau remembered a quote from Morihei Ueshiba that said, "The real purpose of the martial arts must be to purge oneself of petty ambitions and desire, to obtain control of one’s own character." So, with that thought firmly in mind, he decided to build an apolitical dojo in his backyard.

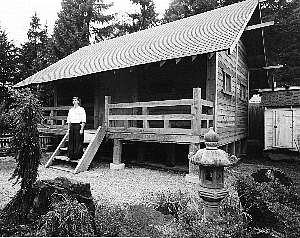

The construction project began with Lau studying books on wood-frame construction and Japanese architecture. [EN3] Once he had a vision, he priced lumber and looked into permits, and did all the other things needed to keep the 360-square foot structure both legal and affordable. Next he had a rock’n’roll party -- he had rocks, and had students come over to roll ‘em. Finally, he started construction. Over a period of about thirty months, the land was cleared and the cedar structure built. Out of pocket cost was about $6,000, including the $600 he paid to obtain the straw tatami from Steve Armstrong’s old karate dojo in Tacoma. [EN4] The structure was featured in The Bujin in August 1981 and Black Belt in October 1986.

Dojo exterior, 1981.

Dojo interior, 1981.

On August 8, 1980, Lau, then ranked 4-dan through Japan, resigned as the chief instructor of the Washington Aikikai, and since then he has received no additional dan gradings. On the other hand, he remained actively involved in teaching, training, and developing police defensive tactics.

Until the 1960s, policemen were taught to throw suspects to the ground by their hair or to choke them into submission using sleeper holds. If that didn’t work, then the policeman simply whacked the suspect alongside the head with a blackjack or nightstick. But with the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s, such actions led to charges of police brutality. So, to avoid lawsuits, departments became interested in teaching uniformed officers different methods. In general, the new methods involved locks of fingers and wrists, or stick strikes aimed at shins and ankles.

While such changes resulted in fewer complaints about police brutality, Lau’s search for personal character development was not doing so well. Much of the reason was that his job had changed. No longer a uniformed officer, Lau now worked undercover in narcotics. "Working undercover," says Lau, "after awhile you forget who you are. Are you an undercover cop playing a drug addict, or a drug addict playing an undercover cop? The roles get all mixed up."

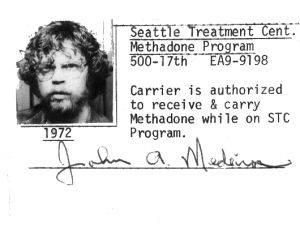

Seattle narcotics detective Lau, 1972. The name was that of a

relative

living in Hawaii. "When undercover, always use something close," says

Lau.

"That way you don’t accidentally forget it." (Lau didn't actually need

methadone, but found having a card made it easier to convince

drug

dealers that he wasn't a cop.)

And, with his roles mixed up, Lau’s personal life began heading downhill fast, and this contributed to a divorce. That happens, says Lau, when you don’t talk to the other person much. Fortunately the split was reasonably amicable – Lau freely admits that the fault was at least half his -- and as a result he was able to keep his dojo.

But that wasn’t the worst of it. As Lau told Kregg Jorgenson in 1994: [EN5]

Then he proceeded to tell me about two elderly Chinese women who were robbed in their homes and murdered. He said the residents of Chinatown were afraid of the man whom they believed did it, and were fearful something worse could happen. He even offered me $25,000 to kill the man who he said was responsible. I was familiar with the name he gave me [Benjamin Ng], and the man was, in fact, a suspect in the murders, only we (the police) didn’t have enough to go on to make a case. There just wasn’t enough evidence.

I told him I would look into it, which I did. And the more I looked into it, the more I realized that maybe the old man was right. It was a gut-level feeling… That’s when I began considering taking the old man up on his offer, only it wasn’t just the idea of the money. I guess I became obsessed with it because I started following him around, studying his routine and habits. It must have been apparent because I was asked to see a psychologist and placed on sick leave. The psychologist thought it was stress related because of the fifteen years on the job, with the last nine years spent working undercover.

… It wasn’t long after that when I got a call asking me where I might find the suspect and a few of his buddies. The call was from one of our detectives in Chinatown, from a place called the Wah Mee Club, a back alley, private, after-hours, Chinese gambling club. The guy and two others had robbed the people who were there that night. Then they tied them up and went down the line shooting the gamblers in the head. They murdered thirteen men and women.

The next morning [February 20, 1983] I walked into the psychologist’s office and threw a newspaper down on his desk. He couldn’t miss the headlines because it was the largest mass murder in Seattle’s history.

In retirement, Lau was interested primarily in getting some balance back into his life. It took four or five years, but one day he realized that "Real life isn’t like the movies, and in spite of our best intentions, we can’t always change the way things happen."

In February 1987, Lau appeared with his student Neil Yamamoto on the cover of Black Belt. After seeing a copy, Lau’s friend Wally Jay telephoned to say, "How come you make da cover, brah? I never make da cover!" Lau replied, "All your pictures show you beating up the white guy. Mine shows it the other way around!"

Black Belt cover, February 1987.

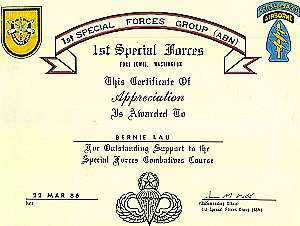

Meanwhile, Lau continued working on his police defensive tactics program. "Through training, research, and further development, we can get better at this," he said. Officers and defensive tactics instructors he worked with included Hawaii’s Julian Shiroma, Montana’s Robert Banis, and Washington’s Bob Bragg, Jon Frantzen, and Scott Wayne. He also taught a 1st Special Forces combatives course at Fort Lewis, Washington, in March 1986. One of his fellow instructors at the Special Forces course was the California aikijujutsu teacher Don Angier, with whom he continues to have a close relationship.

"This Certificate of Appreciation Is Awarded to Bernie Lau for

Outstanding

Support to the Special Forces Combatives Course. 22 Mar 86."

The defensive tactics program culminated in a series of professionally produced videotapes. In these tapes, Lau and his training partners wore traditional Japanese clothing and included historical background so as not to alienate aikidoka, but the techniques themselves emphasized law enforcement tactics. The combination seems to have worked, as the tapes have proved popular with both customers and reviewers.

Whether doing aikido or defensive tactics, Lau stresses that awareness is more important than technique. "With a family fight call," Lau told Seattle Post-Intelligencer reporter Marcia Friedman in 1982, "the officer usually gets hyper and runs right to the door. I teach them to do deep breathing and relaxation exercises on the way there. I stress peripheral vision. A husband could be waiting in the bushes with a shotgun." [EN6]

Toward introducing this concept to his students, Lau would sometimes approach a student from behind, stick a gun barrel into the unwitting trainee’s neck, and then say, "You’ve got three seconds before I pull the trigger." He doesn’t do that any more, though, fearing that somebody will have a heart attack, and several did soil their pants. That said, there were also a couple who pushed the barrel aside and said, "Hi, Bernie."

Such awareness (and sanguinity), says Lau, is an integral part of aiki.

Aiki,

he says, is the act of destroying your opponent’s will to fight. Aikijujutsu

is the art of creating an aiki situation. And finally, aikido

is the practice of aikijujutsu as a way of life.

If interested in organizing a seminar with Bernie Lau, contact Neil

Yamamoto at neil@yamamoto.net

Online

Jorgenson, Kregg P.J. "One-on-One with Aikijujutsu’s Bernie Lau," Full Contact, August 1994, 41-43.

Lau, Bernie. "Aikido For the Modern Samurai," The Bujin, 5:11 (June 1982), 30-33.

-----. "Dojo Plans," The Bujin, 5:1 (August 1981), 18-23.

-----. "The History of Aikijujutsu: The Style of Royalty," Black Belt, 25:2 (February 1987), 20-24.

-----. "An Introduction to Police Defensive Tactics," Journal of Non-Lethal Combatives, November 2001.

Lau, Nit Wan. "Lau King Fai: A successful Hilo merchant," Hawaii Tribune-Herald, October 8, 1989, 15; see also Ashlee Matsui, "Hilo Dry Goods," http://www.k12.hi.us/~kchang/hdgoods.html

McCormick, Gail E. "Lau’s Law: Washington Instructor Initiates a New Training Statute – Realism," M.A. Training, 15:2 (Summer 1988), 30-33.

Nelson, Gail. "Aikijujutsu vs. Aikido: The Transition from Deadly Combat to Gentle Self-Defense," Black Belt, 24:2 (February 1986), 34-38, 102-103.

-----. "The House that Lau Built," The Bujin, 5:1 (August 1981), 14-17.

Stringer, Michael. "What is the Perfect Dojo?" Black Belt,

24:10

(October 1986), 48-52, 83.

To order, Send check or money order to:

For faster service email us to tell us what you just bought!

Endnotes

EN1. From the 1860s until the 1950s, most US states (and not just southern states) had laws prohibiting non-white men from marrying white women, and the federal government had a law (the Mann Act) prohibiting non-white men from transporting white women across state lines. Boxer Jack Johnson is the most famous example of someone convicted under such statutes, but as late as September 1950, a Japanese American wrestler named Don Sugai was prosecuted in Boise for transporting a white woman across the Idaho-Oregon border.

EN2. The Northwest’s first female aikido teacher was probably Fujiko Tamura Gardner, who started a training group in Tacoma’s Fircrest neighborhood in 1973. In Seattle, female pioneers included Mary Heiny, who started a separate training group in the Green Lake neighborhood in 1976.

EN3. Recommended texts include:

EN5. Kregg P.J. Jorgenson, "One-on-One with Aikijujutsu’s Bernie Lau," Full Contact, August 1994, 41-43. Reprinted courtesy Kregg P.J. Jorgenson.

EN6. Marcia Friedman, "Veteran cop finds peace,

harmony

in art of Aikido," Seattle Post-Intelligencer, February 14,

1982,

H1.