by Don Angier

First published in Aikido Journal, 119, 27:1 (2000), 16-23. Copyright © Aikido Journal, 2000. Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

I was born in 1933 in Utica, New York. My father was of French extraction, but always claimed to be Irish because my paternal grandfather had emigrated from Ireland where the family had lived for generations, descended from the Earl of Balfour. My mother was Mohawk Indian.

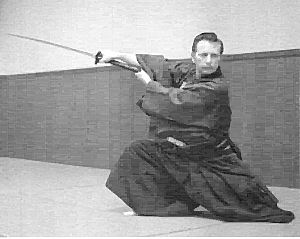

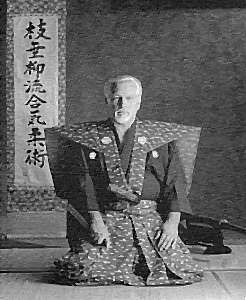

Angier at the Lynwood, California, dojo, 1969

Looking back, I can see now that we were poor, but I never realized it while I was growing up. We always had clean clothes, a clean if not fancy flat, and food on the table. Our neighborhood was what would be known today as a ghetto. Most of our neighbors were, like us, strictly blue collar, and most had just emigrated from Europe. World War II was on in Europe, and they luckily escaped before Hitler and his gang got to them.

Most were German or Austrian, plus a few Polish, Italians, and French. Names like Weiss, Schleicher, Eichler, Bick, Carbone, and La Fleur come to mind. Never did I see an argument or an act of intolerance among them.

The movies and the news broadcasts kept telling us how much we should hate the Germans, yet I was living in the midst of a large, mainly German colony who did nothing more sinister than brew beer in one of several breweries. Consequently, I was not a propaganda convert. I include this information because it was important for my attitude when I met my teacher.

When Japan bombed Pearl Harbor, I remember someone suggesting that we tear out all of the cherry trees in Washington, DC, because they were a gift from Japan. I remember thinking that it was stupid because trees are obviously apolitical. Perhaps that is why I did not reject out-of-hand the first Japanese (or Asian for that matter) that I ever saw in the flesh. A man who was to become the biggest influence in my life: Kenji Yoshida.

Kenji Yoshida (ca. 1903-1954) during his later years.

Just before the Pearl Harbor attack, and again for a short time after the war, movie theaters showed a series of movies featuring a character named "Mister Moto" based on a series of books by John P. Marquand.

Although Moto was Japanese, his loyalty was to justice rather than to any government. He worked in an "Interpol" type capacity. At least once in every movie he was forced to use jiu-jitsu on his opponents, who were always much larger than he. When someone would comment, "Wow, judo!" Moto was always quick to say, "So sorry! Jiu-jitsu please, not judo!"

Well, he was short, I was short, and he handled his enemies with ease, as I would have liked to be able to do. He was my hero and I wanted to be him, just as kids today want to be Batman or the Terminator. I scoured the library for books on jiu-jitsu, but during the war, any book that glorified anything Japanese had been removed from the shelves. I did, however, come across an old magazine at a relative’s home that depicted two judoka doing a seionage (shoulder throw). The uke (partner) was upside down, right over the tori’s (thrower’s) head. I spent weeks studying that picture to try to figure out how it was done, but to no avail.

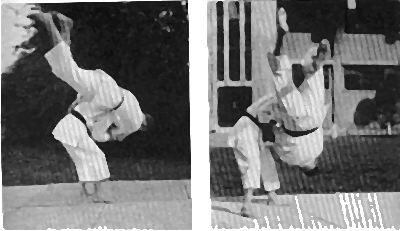

Shoulder throw (Seionage). From Gunji Koizumi, Twelve Judo Throws

and Tsukuri (London: The Budokwai, 1948). The thrower (tori)

is Koizumi; the person being thrown (uke) is Trevor Leggett. Copyright

© The Budokwai 2001. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Later, when I was 15 or 16, I was playing volleyball at Butler playground when I looked over at a bench near the fence. I was immediately flooded by mixed emotions: excitement, fear, disbelief, and others I cannot describe.

The man came back on several occasions. I made up my mind that I had to talk to him. I dug up that old judo picture and brought it with me. After all, the word during the war was that all Japanese were jiu-jitsu masters and could toss you with ease in a second.

I took a break from the game one day and pretended to rest against the fence a few feet from the man. I took out the photo and slowly, and I thought inconspicuously, edged towards the man. Finally, I got enough courage and thrust the picture under his nose and blurted, "Can you do this?" He was quite surprised, but finally looked at the picture and nodded yes. Well, the silence was broken and he had not attacked me, so I said, "Will you teach me how to do that?" He said no, got up, and walked away.

He was absent for several weeks. I had screwed up my chance to be Mr. Moto. Then one day I looked over and he was back. After the ball game was over, he motioned me over and asked if I still wanted to learn to do the shoulder throw. I said yes, of course. He said it would take a long time, would be very difficult, and no one was to know. I was on my way to becoming Mister Moto!

About three-quarters of a mile west of the playground were the city limits. Half a mile farther was a series of bridges that spanned the Mohawk River, Erie Canal, and Barge Canal. We took the footpath along the Barge Canal and came to a brick building that, in days gone by, had been a way station for changing mules that pulled the barges along the canal. Yoshida Sensei was temporarily staying there until a loft that had been promised him by one of his customers became available. It was sturdy, Sensei had cleaned it up, and power and water was still hooked up to it. Sensei lived in what had been the office area, and one of the other rooms became the dojo. We covered the floor with large flattened cardboard boxes we obtained from the Durr Packing Company, a nearby slaughterhouse. I knew about the boxes because we kids used to take them and slide down the hills in the snow. The boxes were covered with wax to prevent the cow blood from leaking out, and working on them soon made them too slippery to work out on. We next built a two-by-four frame and covered it with planks and old rugs that we procured from the nearby dump. This was our mat for the next few months. The roof over the mat area leaked when it rained, so classes were more academic; learning how to pass swords back and forth, cleaning the sword, etiquette, Japanese language for me and English for him, and other such things were explored.

Of course we did not have a real sword, but Yoshida had carved each us each a good bokken [wooden sword], and he had a hakama [traditional trousers] which he had been given in the camp. Kendo was allowed in the camp ["relocation center" where Japanese Americans were sent during World War II] after awhile, and most with a martial arts background participated, although Sensei stated that many were afraid to play for fear of being placed under suspicion of being a militarist by the guards.

Finally the loft became available. In the rear of a house just half a block away from my house, there was a three-garage outbuilding with storage lofts above each garage. The lofts were not divided by solid walls, just two-by-four framing. No one else was using the lofts, so Sensei actually had the whole space for himself.

Yoshida Sensei worked as a handyman. In the summer he cut lawns, cleaned out attics and garages, ran errands for the elderly, did minor repairs, and was quite a good small tree pruner. The winter was very busy. Shoveling snow from driveways and walkways, cleaning and hauling ashes out of the coal furnaces, shoveling out the trains snowed in at the station, etc. To his many customers, he was simply known as "Ken."

In the summer it was easier to attend classes because there was no school, the days were long, and Sensei finished his work early because I often helped him. I remember one incident that showed me a side of his character that I had never seen. We were cleaning out a backyard for some people who had recently moved into the house. The man came out and told Sensei that he wanted the small shed cleaned out so his son could use it as a playhouse. He punctuated his instruction with, "Make sure you don’t get any Jap smell on it." I was furious and was about to go after him, but Sensei stopped me. He said that the man was sick, and that we do not harm sick people. I did not understand, but cooled off. When we finished cleaning out the shed, the man came out to inspect the work. Of course it was spotless. Sensei then said to him, "You will notice that I was very careful not to get any Jap smell on it." The man became embarrassed and apologized.

There was no regularly scheduled class time. Whenever the mood struck, we practiced, and I was always in the mood. I skipped school so often to practice that I had to repeat one semester in high school to make up the work. The first thing that he taught me was the seionage that was depicted in the photo I had shoved under his nose. Then he said, "Now you know seionage. Now forget that stuff and start learning jiu-jitsu."

We practiced rolling, falling, sitting seiza [a formal kneeling position] and moving in shikko [moving from that formal kneeling position]. After that, things were not taught in any particular order, which I hated. I am a very meticulous person and I like things to be in a logical progression. Consequently, I made copious notes after every class and developed categories that made sense to me, placing the forms in these sections as I learned them. This was the beginning of the systemization of the art, and was strictly for my own edification.

Although Yoshida Sensei spoke English poorly, he had a way of getting things across by body language and using simple physics demonstrations. The main thing he stressed was that the forms were only examples of how the principles were to be used. As long as the principle is used correctly, the form itself is of little importance. Only basic moves and forms have names. It would be impossible to name every form. He told me to name them anything I wanted as long as it helped me to remember them.

He said that in the old days, weapons were more important, and that the hand arts were used when you didn’t have a weapon or were in a castle or clan mansion where drawing a weapon was punishable by death unless you were a member of the household guard on duty. To have a weapon and not use it was, in his opinion, stupid. He loved going to movies, and we went often. He was always amazed when the hero tossed away his gun and took on the villain with his bare hands.

Sensei insisted that the sword, spear, naginata [halberd or glaive; a polearm], jo [stick], and the hand arts were all the same. The sword was taught first, then the corresponding hand application. To begin a new technique, he would show me the attack he wanted, then he told me to attack hard. I attacked and found myself either crumpled at his feet or piled in a corner. Then he would ask me to do the same thing. As you would imagine, it was embarrassing to say the least. But finally through infinite repetition I would get it. Something that helped me quite a bit was realizing that by trying to ignore the pain and concentrate on what he was doing to me, my mind became clearer and I could see what he was doing. This also caused my threshold of pain to increase considerably. I realized that "Tension equals pain."

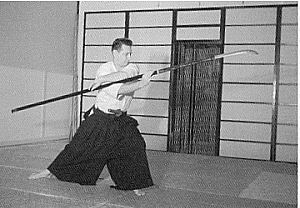

Training in naginata at Westlake Park Dojo, 1955.

Sensei took falls and joint locks in the beginning, but after a couple of years stopped taking hard body falls. In the concentration camp he had contracted silicosis, a lung disease similar to a combination of tuberculosis and emphysema from breathing in the fine dust that filtered through the cracks in the walls and floors. Each time he breathed, the silica in his lungs was tearing them up, and he was getting progressively worse.

I regret that I did not pay more attention to such things as Sensei’s past and his family history. But to understand this, you have to put things in their proper perspective. First, there were no such things as martial arts dojo in those days on the East Coast. Maybe a judo dojo here and there in cities with large Japanese populations, but generally they were non-existent. Maybe one percent of the population had heard of martial arts, and fewer cared. Remember that it was just after the war. Hundreds of thousands of Americans had lost fathers, sons, brothers and sisters, and other relatives to the Japanese.

Pretty much anything Japanese was hated. However, I was learning strictly for myself, and such things were of no importance to me. Who would have dreamed that Japanese martial arts would ever become popular? The mere idea was as ludicrous as crab-racing dojo becoming popular. The idea that I would ever end up teaching was even more farfetched.

Another factor was that in the 1940s and 50s, children did not ask personal questions of adults, even those in your own family. It was considered very rude. There was a definite line between adults and children. Even among adults there was a respect for privacy that we seldom see today.

There were, however, certain things that Sensei felt it necessary for me to know. Among them was that his family had been very prominent in samurai times. With the help of the maps in my high school history books, he showed me that his family had originally come from Satsuma in southern Japan. They had fought in the Satsuma rebellion on the losing side and relocated to Hokkaido in northern Japan, then to the Tokyo area. He never mentioned the Daito-ryu or Sokaku Takeda.

His father was considered important in martial, political, and literary circles, and was a member of an organization called the Black Dragon Society , a very influential ultra right-wing nationalist organization. The Black Dragon Society changed its name after it completed one goal and adopted another one for good luck. It was known variously as the Ronin Society, the Grass Roots Society, the Cherry Blossom (Sakura) Society, the Amur River Society, and others. At one time, when it was known as the Sakura Society, it met in the old Kobukan Dojo of Morihei Ueshiba, the precursor of the Aikikai Hombu Dojo. It is not known if Ueshiba had knowledge of this meeting, but in my opinion a man of his perception would know everything that went on around him, especially in his own dojo.

They slowly took over the government beginning at the turn of the century and Japan embarked on its expansionist policy which ultimately led to the destruction of the country by the Allied Forces. If you were not totally with them, you were considered an enemy and a risk. Because Kenji Yoshida was vocal in his opinion against the new direction the government was taking and Kotaro Yoshida, his father, was very active in the new government, there was a serious rift between them. So much so that Kenji Yoshida feared that he and some of his close friends had been targeted for removal. Japan had been recruiting people to go to Argentina, Brazil, and other South American countries to form new villages and set up farm communes. Most of these junkets were sponsored by large companies in Japan for the purposes of establishing a source of produce for Japan, which was fast becoming short on land, and to introduce a spy network into the area from which they could fan out across the Western hemisphere. Argentina was a neutral country, and the war was at that time confined to China and Southeast Asia. The Argentine government was friendly with the Axis governments, but kept out of the war actively. During World War II, you could find English, American, German, and Japanese ships docked side-by-side in Argentine ports. It was not difficult for Kenji Yoshida to book passage under a different name on one of the ships bound for Argentina.

A young Kenji Yoshida, taken presumably in his home in Japan sometime

during the 1930s. Notice the hanging scroll, which reads "Yanagi-ryu aiki

bugei."

Once there, he was able to get to Costa Rica. Eventually, with the prearranged help of friends among the Japanese tuna fishermen from Terminal Island, California, Yoshida Sensei was brought into the United States.

In those days, Terminal Island was almost one hundred percent populated by Japanese. The tuna fleet and canneries were there, and non-Japanese hardly ever went there. They had their own doctors, lawyers, and other professional people, and did their own marryin’ and buryin’, and there were groups who were helping Japanese relatives and others enter the country. The tuna fleet would sail down to Costa Rica and other coastal locations and the people they were helping into the country would work their way back on the boats. Since they did not always report deaths in the community to the authorities, they kept identities "alive" and matched the new arrivals with the identification of the deceased.

A short time after his arrival, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. When the FBI began rounding up Japanese Americans and nationals in Southern California, Yoshida Sensei went north to the San Francisco area, but eventually was caught in the dragnet. He and other Japanese were held at the former Tanforan Racetrack and then shipped off to Topaz Relocation Center in central Utah.

Overview of the Topaz site. Figure 12-11, page 266, of Jeffrey F. Burton, Mary M. Farrell, Florence B. Lord, and Richard W. Lord, Confinement and Ethnicity: An Overview of World War II Japanese American Relocation Sites (Tucson, AZ: Western Archeological and Conservation Center, National Park Service, 1999 [2000 update with corrections]).

Upon his release from the camp, he worked his way slowly east until he eventually came to Utica, New York. It was autumn when he arrived and he was struck by the beauty of the foliage in the Mohawk Valley. He said it reminded him so much of Japan that he decided to stay.

Yoshida Sensei never talked much about the camp, and I did not even know that they existed until later. He was also quite concerned about being arrested as an illegal alien, did not like having his picture taken, and was uncomfortable whenever police cars passed.

During my high school years, the United States entered the "Korean Conflict," and soon after my graduation I was inducted into the Army. For two months during basic training I was unable to leave the base, but I got a one-week leave after basic and spent the whole time with Yoshida Sensei. I was never close to my real family. They could never really get a hold on where I was coming from. They began calling me the "old man" when I was ten.

I attended the Small Arms Repair School at Aberdeen Proving Grounds, Maryland, and was able to leave every Friday evening as long as I was back by six in the morning on Monday. Sensei was getting sicker, and we both knew he belonged in the hospital, but stubbornness, pride, lack of funds, and fear of being arrested kept him from going.

It was at this time that he finally admitted that he could no longer continue to teach me. But he told me that I had learned most of the principles and that if I built on them, I would be all right and other principles would reveal themselves.

He finally told me that he had agreed to teach me for several reasons. During his absence after our first meeting, he had been watching me to see what kind of a person I was, how much of a temper I might have, and generally how I conducted myself. He realized that he would probably never return to Japan, and he still had an obligation to pass the family art along.

When he started thinking about the odds of finding someone who was not only familiar with what the martial arts were, but had a desire to learn, he was convinced that our meeting was arranged by the gods, and to ignore such a sign would be tempting the wrath of fate.

He said that he considered me a yoshi, an adopted son, such as those adopted by samurai who had no children of their own or those adopted by families who had lost the male heir. My new name was to be "Kensaburo Yoshida." I only use the name when writing to Japan. It usually gets me an answer where a letter from a foreigner most often is ignored and unanswered.

The significance of this responsibility did not become clear to me until much later. I finally realized that I now had the responsibility of finding someone else to train to carry on the art, and I did not feel the least bit confident in my own ability, let alone knowledgeable enough to teach.

I was sent overseas, and shortly thereafter my letters to Sensei began being returned. I finally wrote to the lady who had furnished Sensei the loft. It was then that I learned that Sensei had passed away from pneumonia caused by the silicosis. She had a box of things for me, mostly old pictures that he had brought from Japan. I had my sister collect them for me.

When the Korean Conflict was over, I was assigned to a top-secret project called Operation Castle at Eniwetok Atoll in the Marshall Islands. It was the detonation of the first hydrogen bomb. There were short periods of excitement and around-the-clock sessions followed by longer periods of inactivity and boredom. It was then that I held my first classes for the officers. It kept my skills up and got me out of more than a few unpleasant details.

After Operation Castle I was assigned to Second Army Headquarters at Fort George G. Meade, Maryland. After a brief time as a small arms repairman, I was approached to take over the unarmed combat section of the Officers Leadership Training school. It seems that the former instructor had accidentally killed his assistant and best friend during a training session, then had a nervous breakdown and took his own life. While going through my records as a new arrival, they came across some letters of commendation from officers on Eniwetok mentioning my martial arts classes, so I got the job. I continued in that position until my honorable discharge from the Army.

I could not find work in Utica and decided to go to California, influenced by the fact that there was a large Japanese population there and I would probably find a new jiu-jitsu teacher and could continue my training. What a letdown that was!

I found work almost immediately and set out to find a jiu-jitsu teacher. I discovered the "Little Tokyo" area of Los Angeles and started asking shopkeepers where there was a jiu-jitsu dojo. Most did not even know what jiu-jitsu was, or at least pretended not to know. Finally I found the Little Tokyo Chamber of Commerce. One lady there gave me a list of judo and kendo dojo, and I set out on the rounds.

It was the same thing everywhere I went. Lots of "Japanese only," but mostly that there was no longer any such thing as jiu-jitsu. The best techniques of all jiu-jitsu were incorporated into the sport of judo. After watching a few classes, I knew that judo was not what I was looking for. Finally, I looked in the phone book under "self-defense" instead of jiu-jitsu. There was a school in the Westlake Park (now MacArthur Park) area of Los Angeles that mentioned jiu-jitsu in the ad. I went to see the "Westlake Judo Club."

They taught judo in the first class, then what they called jiu-jitsu in the second. It was quite crude. Kicks to the groin, fingers in the eye type of stuff. I made a deal that I would enroll in the jiu-jitsu class and pay a little extra to rent the mat for personal practice time before the regular classes started. Some of the students saw me practicing and asked what I was doing. When I explained, some asked me to teach them. This angered the teacher and I was asked to leave.

I started my own dojo in a coworker’s garage in Covina, California, and my first students were those from the Westlake Judo Club who had asked me to teach them. About a month later, I received a call from the owner of the Westlake Judo Club. He offered to sell me the dojo. I did not have a job, but he made the offer with very liberal terms, so I accepted and moved into the dojo. That was in 1955.

I was extremely lucky in finding a wonderful student named William Hepler. It happened that he was as obsessed with the art as I was. Not only that, he had talent as well. We became best friends, so much so that I became the godfather of all his children.

William Hepler at Westlake Park Dojo, 1955.

Bill worked graveyard shift at the main Los Angeles Post Office. For almost nine years he came into the dojo three hours before class. Together we worked on categorizing the basics of the art and how to make them as precise as possible. We worked out pragmatic counters to all of the forms and counters to the counters. It was only with his help that I was able to systematize the art and start listing its scientific principles. If things had gone well, Bill Hepler would have been my "soke dai" [inheritor of the art], but unfortunately he was killed when a driver turned left in front of his motorcycle in October of 1964.

In the 1980s I gave a partial copy of the aiki jujutsu principles to a teacher in Massachusetts for his personal edification. He turned around and made a chart of them which he sells through the mail, and I have heard he now has written a book on them, adding a few of his own to get by the copyright. He represents them as his principles and ineptly tries to demonstrate them on tape. To me this is a betrayal and shows a gross lack of character and ethics. Nowhere does he mention that these are Yanagi-ryu principles.

The 1950s were a wonderful time in my education into other martial arts and artists. There were not many of us in those days, so whenever someone came into town they would look through the phone book and call for an appointment. We were listed under "Gymnasiums." Martial arts were so rare that there was no listing category in the Yellow Pages. I remember one man entering the dojo and observing the class. He was in his thirties, over six feet tall, and his head was shaved. A scar ran from the top of his head to the base of his neck. He looked quite formidable, but after talking to him, he turned out to be quite an interesting fellow. He was well read, played classical guitar, and was a student of an art called "Shinwa Taido," which I had never heard of.

My first impression was right. He was quite a formidable fighter and had been a Marine drill instructor. His name was Walter King. His stepbrother is Dale Jennings, who wrote the books Ronin and The Cowboys, the latter being made into a movie starring John Wayne. We soon became friends. One evening he said that the master of the art was coming from Japan and asked if I would like to meet him. Of course I jumped at the chance. It turned out to be Hoken Inoue Sensei, also known by the name of Yoichiro and Noriaki at different stages. Inoue was a nephew of Morihei Ueshiba.

The group usually practiced in the local teacher’s living room and only a few students would fit in a class at a time, so arrangements were made to have Inoue Sensei’s class and demonstration at the downtown Los Angeles YMCA. We were supposed to use the judo room, but the teacher resented us bringing in another art and he refused to let us have the facility. Instead we used the basketball court.

All during the class the judo teacher, a Filipino named Leo, kept up a steady stream of wisecracks and derogatory remarks to his students, who seemed very interested in what they were doing. The local instructor – I believe his name was Ken Kuniyuki – explained to Inoue what was happening. Inoue Sensei then talked briefly to Mr. Kuniyuki, who nodded and approached the judo teacher. He told Leo that Sensei could tell by his demeanor that he was a highly skilled martial artist and asked if he would serve as uke for him since his students were not up to taking the fall for the next technique. Of course, Leo’s ego would not let him refuse. He sat opposite Inoue Sensei as he was requested and grasped his wrists. Inoue Sensei immediately locked up his arms from wrists to shoulders and sent him flying directly over his head, landing face first with his arms still at his sides. He got up and held his bleeding and broken nose, screaming on his way to the first-aid room.

During the late 1950s, I had an older Chinese man come into my dojo and watch a private lesson, but he left before I could talk to him. He did this several times. Finally, he came in when no student was present and I got a chance to meet him. It turned out to be Ark-Yuey Wong (1898-1987). He was a very famous Chinese martial artist, but I did not know that at the time. No one knew about kung fu in those days. He said he used to do a Chinese version of jujutsu. We would talk about martial arts all the time and he was fascinated with the softness and intricate techniques of Yanagi-ryu.

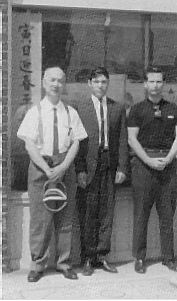

Ark-Yuey Wong, left, with Angier, right, c. 1959

He came up to the Westlake Park area often to visit a friend, Tim Lou, who owned a herb shop a few doors down from the dojo. I would close the dojo and we would sit in Mr. Lou’s back room, have tea, and just visit. However, Mr. Wong’s accent was almost indecipherable when he became excited about a subject, so Mr. Lou would slow him down and let me know what was going on. Slowly, he began showing me some of his skills. It would be very easy to underestimate this mild-looking, elderly man. He was indeed a wonderful man and artist, and I must admit that some of the things he showed me helped me understand my own art more fully.

I had opened a branch dojo in Lynwood, California, in about 1962, closed the Los Angeles dojo in late 1964, and moved to Sherman Oaks, where I opened another dojo. This one did not work out, so I closed it when my one-year lease lapsed. The Lynwood dojo became the main, and only, dojo, and I taught there for thirty years.

For a time I formulated a kyu-dan ranking system because the public expected it. But I finally realized that I spent too much time on trying to appease the students and they were too concerned with the color of the rag they were wearing around their waist.

I finally dropped the ranking system, closed the commercial dojo in 1987, and now teach the way I want them to learn, slowly and precisely.

I take only a few students at a time and have an extensive waiting list of students who wish to study at the dojo. I do not advertise or have a listed phone number and do not pander for students.

The usual time on the waiting list before being interviewed for acceptance is one to three years. I rarely accept anyone under twenty-one years of age and a gut feeling is more important to me than any list of previous dojo and arts they have studied. In fact, a list of various dojo shows me that they do not have dedication or a "stick to it" nature. I call them dojo tramps and won’t waste my time on them when serious students are more deserving of my attention.

I am pretty much a recluse and do not know or care what other people are doing. I am definitely not into politics or associations. I have never seen one that has not turned former friends against each other within six months and ego rears its ugly head to the detriment of the art. I am too busy teaching to bother with such things.

Formal portrait by Toby Threadgill, Dallas, Texas, 1990

Yanagi-ryu is such a complicated and exacting art that it can only be taught in very small groups, usually no larger than six or eight at a time. Basic requirements to enter our dojo include, but are not limited to:

When I began teaching in the fifties and mentioning aiki jujutsu, Kotaro and Kenji Yoshida, and the Daito-ryu, everyone said that I was a phony and there are no such people and no such art as aiki jujutsu. Now aiki jujutsu is the new buzzword, and suddenly we are blessed with a slew of aiki jujutsu teachers. Where did they all come from so suddenly? Where had they been before the name of their art became popular? When you look into their martial arts histyory, they usually turn out to be aikido people who added a few strikes and judo throws, or karate teachers who add in a bunch of throwing techniques.

The same thing happened in the sixties when kung fu became the rage. There was no karate teacher who could get out the paint brush fast enough to write "kung fu" on his windows. Suddenly everyone was a kung fu teacher who had been sworn to secrecy by his teacher whose name could not be revealed under penalty of death. A Hollywood judo teacher even put on a Lone Ranger mask and a judogi and took out ads on the back of comic books and magazines calling himself "Honorable Mister Kung Fu." He wore the mask, so the ad stated, so that he would not be killed by the Chinese Tongs for revealing the secrets to non-Chinese.

I guess I missed out on a lot of money by not falling into that fad. I have always taught the same thing and never pretended to teach anything else. I now do several seminars each year, mostly in Northern California and in the Southwest. I have given seminars at the FBI Academy and the US Embassies in Bangkok and Singapore, and now people in several foreign countries are making overtures for seminars. Seminar arrangements are usually made through Mr. James Williams of the Bugei Trading Company in San Marcos, California.

But my main focus is on my students. After all, a teacher is not a teacher

without students, regardless of titles and regalia. A martial artist is

judged on his character and performance. A teacher is judged on the performance

and character of his students.