Interview with Takashi Nonaka, September 2, 2000, conducted by Curtis Narimatsu with input from Eric Nonaka. Edited by Joseph R. Svinth.

Copyright © 2001 EJMAS. All rights reserved.

All photos courtesy Takashi Nonaka.

The oldest of eight children (three boys and four girls), Takashi Nonaka was born on Big Island of Hawaii on May 8, 1925. His grandparents were from Kumamoto Prefecture, Japan, and his father, Satoru Nonaka (1903-1986), was born there as well.

Takashi Nonaka, February 1987

At home, Mr. Nonakaís parents spoke only Japanese, and during the summer, he spent a lot of time at his grandparents, who also spoke only Japanese. As a result, he still speaks Japanese with their southern accent.

Unlike many Japanese Americans, Mr. Nonaka also reads Japanese well. The reason is partly that his fatherís drinking buddy was the principal of the local Japanese language school. Mr. Nonaka didnít want to attend the Japanese school, or even learn to read Japanese. After all, the school was a 2-1/2 mile walk from the Nonaka house, meaning that it would be dark by the time he would get home most nights. But if he skipped or misbehaved, then his father heard about it almost instantly. And, as this was in the days before Child Protective Services, the first thing his father would do upon hearing of his misbehaving was to slap him. Once that detail was out of the way, then Mr. Nonaka got to explain what he had done or not done. If the transgression was no big deal then his father would say, "Donít do that again." But he would never apologize for that first slap. However, if the young man was wrong, well, of course then it was another slap. Not liking the slaps, the young man attended both the American and the Japanese schools and always made sure to behave himself. Or at least avoid getting caught -- being hungry after school, he and his friends would climb mango trees for the fruit, and the farmers didnít like that. Since it took time to climb down, to avoid capture the boys jumped down to the ground, and today Mr. Nonaka wonders if that wasnít a contributing factor to his subsequently requiring two complete knee replacements. "We do things when we are young, not thinking about how they will affect us when we get older," he says.

Iwazo Nonaka with his son Satoru and his daughter-in-law Kiwa Miyazaki Nonaka, 1923; this was their wedding photo.

However, another reason Mr. Nonaka reads Japanese is that his family didnít own a radio and television hadnít come to Hawaii yet, so at night he read. Much of this reading was in Japanese, because those were the only magazines and newspapers his father bought. Mr. Nonaka especially liked the stories of the famous Japanese swordsmen.

Although not an especially large man, Mr. Nonakaís maternal grandfather Tatsuhei Miyazaki had been a sumotori during his youth in Kumamoto. While in Japan during the 1960s, Mr. Nonaka met an elderly man who had known Grandpa, and this man said that every time sumo season came, Grandpa abandoned the farm and headed straight to the ring, that was how much he loved his wrestling.

Meanwhile, paternal grandfather Iwazo Nonaka encouraged his son Satoru to wrestle. (The elder Nonaka never wrestled himself, but was a very enthusiastic sideline coach.) Being comparatively small, Satoruís solution was to train harder than others did and therefore have better technique. As a result Satoru became a Big Island champion, and when he retired he was promoted to oyakata, or trainer of sumotori.

Takashi and Satoru Nonaka, 1928. The latterís ring name was Midorigawa, after a stream near the Nonaka home in Kumamoto Prefecture, Japan.

Tatsuhei Miyazaki and Iwazo Nonaka did not get along at all well, due in large parts to disagreements over sumo. So imagine Grandpa Miyazakiís disgust upon learning that his only daughter Kiwa (1904-1994) wanted to marry Satoru Nonaka! Indeed, the man was so incensed that he refused to give his blessing for the marriage, and as a result the couple ended up getting married at the go-betweenís church rather than the brideís fatherís church. But of course Grandpa Miyazaki eventually forgave his daughter, grew to like his son-in-law, and doted on his grandchildren. Therefore it wasnít until many years later that Mr. Nonaka heard this tale.

In 1932, at age 29, Satoru Nonaka lost his arm below the elbow in an accident. He was not totally incapacitated and a local plantation hired him at a low wage, but his wife had to get work as a field hand and she had never had to work outside the home before. Mr. Nonaka was old enough to see how this changed his father, an enormously proud man who always insisted on tying his own shoes, even with his one hand. And he drove the car one-handed, too, despite its having a manual transmission. After his accident his father became bitter and drank a lot of sake whenever he attended a wedding or visited a friend, and from age 13, Mr. Nonaka went along to drive him home.

One day Mr. Nonaka asked his mother how she put up with her husbandís short temper and constant scolding. "We cannot change him," she replied. "So we must change ourselves, and just accept that he is that way."

"I was young and didnít understand her response then," says Mr. Nonaka today. "But now I realize that hers was the principle of aiki, of blending mental and physical energies, and that is what guides my life."

As a teenager, Mr. Nonaka trained in kendo. The dojo was at the Hilo High School gym, and in July 1941, at age 16, he tested for shodan, or first grade. He passed the test, but the certificate had to be sent from Japan. Mail was slowed because of the tensions between the United States and Japan, and before the certificate arrived the Japanese Navy bombed Pearl Harbor. But the lack of a certificate was a good thing, really, because on December 8, 1941, the FBI began questioning all dan-graded kendoka on suspicion of being enemy agents.

There was no judo or kendo in Hilo during the war, but afterwards judo resumed. Mr. Nonaka trained in judo for a time, and it was then that he first learned to do ukemi, or falls.

In 1951 he started a career as the manager of an agricultural and plant tissue analysis laboratory in Hilo. This took much time and mental energy, so he quit training in judo. Then one day in 1955 he attended a lecture given by the Japanese aikidoka Koichi Tohei. "I was impressed with what he had to say, and I signed up that same night," says Mr. Nonaka.

Tohei Sensei first came to Hawaii in 1953, at which time the Hilo aikido club was led by a man named Kiyoshi Nagata. Mr. Nagata left the club during the early 1960s, and Mr. Nonaka doesnít know what happened to him after that.

Most of the members of the club in the early days were teenaged Japanese American boys fascinated by the moves, which, while commonplace now, seemed like magic back then, when nobody understood how they worked. One the youths who stayed with aikido was Clyde Takeguchi, who started an aikido club in Madison, Wisconsin, in 1967 and six years later established the Capital Aikikai in Silver Spring, Maryland. There were a couple European American youths, too, including Bernie Lau, who started an aikido club in Seattle in 1968.

Because he was about the same age as Tohei Sensei (born 1920) and already knew how to fall, Tohei Sensei often selected Mr. Nonaka as his uke, or partner. In those days, techniques didnít have names. Instead Tohei Sensei would merely point to his arm or jacket, say one hand or two, and boom! Over Mr. Nonaka would go. It was hard work, but after awhile he got very good at falling, and better yet, he got to feel the techniques. "You cannot learn totally by watching or hearing or reading," says Mr. Nonaka. "You must feel it."

During subsequent visits to Hawaii, Tohei Sensei sometimes stayed at the Nonaka home. Since Mr. Nonaka spoke Japanese well, this meant that conversations were easy, and as a result he got extra lessons in the philosophy of aikido. On the mats, one just learned waza, or technique, but afterward one learned the philosophy, and that was where aikidoka who only spoke English missed out -- because of how they were taught, they believed technique was everything, when really the philosophy was at least as important.

Of course, Tohei Sensei was also very hands-on, and because a senior aikidoka on Maui, Shinichi Suzuki, was a police captain, he often gave special classes to Hawaiian policemen. Dealing with 230-pound Polynesian policemen was not the same as dealing with 140-pound Japanese college students, and no matter how much Tohei Sensei told the policemen to move from the hips, they always insisted on using their arms and shoulders instead. Furthermore, they asked questions in a blunt way that no one in Japan would ever consider, let alone do. Together, these things made Tohei Sensei spend considerable time thinking about how to transmit his ideas better.

After training, the policemen would take Tohei Sensei out for lunch. Lunch in those days meant drinking a lot of beer, and after returning Tohei Sensei would have to take a nap to prepare himself for his evening classes. One day at the restaurant, a fight broke out behind them. As a policeman, Mr. Suzuki stood up to stop the fight. But Tohei Sensei put his hand on his arm and said, "No, wait a minute," and then began moving all the tables and chairs out of the way. Once that was done, Tohei Sensei said, "Okay, go stop the fight." Which Mr. Suzuki did without much fuss, because by then the fighters were tired. After he returned, Mr. Suzuki asked Tohei Sensei why he had delayed him. "Well," said Tohei Sensei, "there were no weapons and no one was beating the other too badly. So the worst that would happen was a black eye or something. But if you stepped into the middle, then someone might be pushed over a table or chair and hurt himself. So first we moved the tables and chairs." Mr. Suzuki recognized that as an important lesson in aikido applied to daily life.

From late February until mid-April 1961, aikido founder Morihei Ueshiba was in Hawaii. While visiting the Big Island, Ueshiba Sensei stayed at the Nonaka home, and as host, Mr. Nonaka took the Founder and Tohei Sensei to see the volcanoes. It is a long, boring drive, and so both passengers soon fell asleep. Ueshiba Sensei sat in the back seat, and his head bobbed like anyone elseís. However, Tohei Sensei in the passenger seat sat bolt upright, swaying from side-to-side like a Daruma doll. Later Mr. Nonaka told Tohei Sensei that at least in sleeping in cars, he was clearly the senior here. Tohei Sensei laughed and said that this was the result of his Zen training. Whenever he returned to Japan from abroad, he always went to a monastery for two weeks to restore his equilibrium. During free time at the monastery, you couldnít lie down, but you could sleep sitting up. So he always went to sit near a waterfall. That way if he swayed too much heíd fall in the pond, and not liking to get wet, he had learned to sleep sitting straight up.

![TOHEI AND NONAKA]](nonaka/ToheiandNonaka.jpg)

Koichi Tohei and Takashi Nonaka

While meditating, Tohei Sensei had also realized the importance of the hara, or center, and to help English-speaking people better understand the idea, he had created the phrase "the one-point." If your mind focuses on the one-point, Tohei Sensei believed, then you were strong; if you let it wander, then you grew weaker. This is an interesting concept, too, because you canít learn it by talking or reading about it, you have to feel it. Toward developing the one-point, Tohei Sensei worked on a throw he called the air-throw (kokyu-nage). It looked like a judo hip throw, but it was not. Instead it was a throw perfected by judoís Kyuzo Mifune that no one else could do. To do this throw, you almost had to read the opponentís mind, as the trick was to make it so that the opponent essentially threw himself. All Tohei Sensei had to do was be in balance, and of course that was no problem for him. And it was just the neatest thing because you hardly even felt him touch you: one minute you were up and the next you were flying through the air, getting ready to practice your breakfalling.

During his 1961 visit to Hawaii, Ueshiba Sensei gave many speeches and demonstrations, and Mr. Nonaka was an official translator. Translating "Good evening and thank you for inviting me to Hawaii" was easy enough, but after that the Founder began his usual rambling esoteric discourse. And, while Mr. Nonaka understood the words, he had no idea what they meant. So he was honest and said, "Iím sorry but my Japanese is too poor to translate what he said. But if I come to be of his age, I hope I become wise enough to understand what he said today." The crowd applauded and Ueshiba Sensei beamed, and after returning to Japan he asked his seniors why they couldnít understand him as well as this nice young man from Hawaii. Tohei Sensei howled when he heard this, thinking it one of the funniest things heíd ever heard.

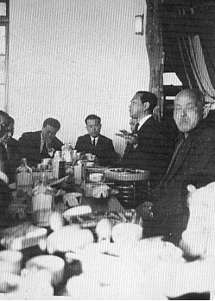

Hilo, 1961. Left to right: Tamura Sensei, Yamamoto Sensei, Tohei Sensei, Ueshiba Sensei, Mr. Nonaka, Uemura Sensei, Mr. Murakane

While traveling with Ueshiba Sensei, Mr. Nonaka asked questions and if the Founder felt like answering, he did. On technical topics, Mr. Nonaka found that Ueshiba Sensei usually gave explanations that were too esoteric to make much sense. However, one part of Ueshibaís philosophy that Mr. Nonaka really liked was this analogy, which compared life to a flowing river: "Human beings are in the river," said Ueshiba Sensei. "Some swim nicely and others are struggling. If you jump in to save the ones who are struggling, you might be drowned. But if you stay on the bank, then maybe you can throw them ropes or warn them of cataracts and waterfalls ahead. The purpose of aikido is to throw ropes to people who are struggling, to give them tools necessary to avoid hazards."

Asked how he got started in aikido, Ueshiba Sensei told Mr. Nonaka that he began training in aikijujutsu after moving to Hokkaido in 1912. His instructor was Sokaku Takeda, who usually didnít trust people, but he liked the young Ueshiba and so let him cook and do other chores for him. In return, Ueshiba learned jujutsu. As he grew older, Ueshiba Sensei began paying more attention to the aiki than the jujutsu, and that was the start of what became aikido. [EN1]

Morihei Ueshiba in Hilo in 1961. The arrows by the basketball backboard point toward Clyde Takeguchi.

So what is aiki? It is hard to translate but it is sort of the coming-together of the mind. There are exercises to develop it, but your mind has to accept it, otherwise you will never get it.

The theories, though, are simple enough. As expressed by Tohei Sensei, they are:

In 1971 Mr. Nonakaís son Eric was graded shodan in aikido. "At the time the Hilo dojo was in need of instructors, so although quite young, the other senior instructors recommended that I take the exam," says Eric, who began studying aikido in 1962, when he was around eight years old. Until Eric earned his shodan, Mr. Nonaka left his training to other instructors, as parents are often too hard on their children. However, once Eric was graded, then Mr. Nonaka took charge of his training.

Part of the training involved waking Eric an hour earlier every school day so that he could practice with his sword. Mrs. Nonaka wasnít too happy about this, but to Mr. Nonaka, this represented shugyo, or "ascetic practices." Lots of people say, "In my class we train real hard, and that is shugyo." But training hard in class isnít real shugyo; real shugyo is what you do outside of class, when no one is looking.

"The waking up early in the morning was small sacrifice for the knowledge gained," says Eric. "My father gave me certain bokken [wooden sword] movements and exercises to learn and over the course of those short years much was gained. I was shown these movements a few times and thereafter I was left alone. My father may not say much but through his guidance, the Hilo dojo instructors are well known for being skilled in doing bokken movements and there are some that can spot his students by how they swing the bokken. I now urge my students to do the same at their homes."

Eric and Takashi Nonaka, 2000

While in college, Eric was graded 2-dan, and as a college senior in July 1976 he went to Japan to participate in the live-in program run by Tohei Sensei. "In Japan," says Eric, "I lived with Koichi Kashiwaya, current chief instructor for the US. [EN2] The honcho in the room, however, was Otsuka Sensei, who is the chief instructor at our headquarters in Tochigi. Also staying there at this time were Yoshigasaki Sensei, chief instructor of Europe and Osaki Sensei, chief instructor in Shizuoka. These young professionals were put in charge of me. As such, we practiced shugyo at all times. This is something I try to stress to my students, that martial art training is not only in the dojo, but at all times."

Since Eric was, physically, the largest member of the group, Tohei Sensei often used him as his uke. After all, it looks better to the audience if the teacher throws some big guy (Eric stood 5í10" and weighed about 205 pounds) than if he throws some guy standing 5í1" and weighing 110 pounds. This was fortunate, too, as Ericís Japanese wasnít as good as his fatherís and so he couldnít have learned except by doing.

Eric received his 3-dan grading from Tohei Sensei in January 1977, the very day he left Japan for home. Today Eric teaches aikido at the Miliani Hongwanji on Oahu, and he was graded 6-dan in early 2000.

Mr. Nonakaís daughter Anne studied aikido while in elementary school and junior high, but gave it up during high school because she had other activities she liked better. Today she lives with her husband and family in West Covina, California.

From December 1967 to April 1968 Mr. Nonaka visited Japan, and he stayed five days at the home of Tohei Sensei. While there, Mr. Nonaka had the opportunity to speak with Toheiís mother, and of course he heard all about what Tohei Sensei was like as a boy. Those conversations helped him better understand Toheiís philosophy.

To illustrate this to beginners, Tohei Sensei used a routine called "the unbendable arm."

To do the unbendable arm, you make one hand into a fist and hold it in front of your body. Then you have a friend try to move the arm. Next you open your hand and instead of putting strength into the arm, you breathe, relax, and imagine your energy flowing out your middle finger like water from a hose. Your friend will have much more trouble moving your arm.

The visualization helps illustrate the flow of ki to beginners.

During early 1968, Mr. Nonaka spent several days visiting Ueshiba Sensei in Tokyo. They talked a lot, and one question Mr. Nonaka asked was why there were no contests in aikido. Ueshiba Sensei replied, "If there are contests, then there are always losers. Heís not happy, and will want to get back at you later. Or you can trick someone. But a person doesnít forget, and you canít trick him twice. Therefore a better way is to win him over by showing him respect. But you have to show him respect first, and that is a true victory, the kind that comes from the heart."

Mr. Nonaka also asked Ueshiba Sensei about the statement that one should practice with joy. "When you learn something enjoyably," said Ueshiba Sensei, "you grasp more. So if you want to help a student, become the uke, the one being thrown. Uke wa sensei da: the uke is the teacher. First give the students a chance to relax."

In September 1971 Tohei Sensei established the Ki No Kenkyukai, or Ki Society, and in May 1974 he resigned from the Aikikai. The reason for the resignation was strained relations between Tohei Sensei and Ueshiba Senseiís son, who had taken over the Aikikai after his fatherís death in 1969. This caused much consternation in the international aikido community, but since Mr. Nonaka was a direct student of Tohei, it was not a problem for him: he stayed with Tohei Sensei.

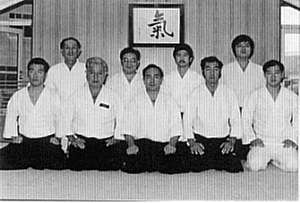

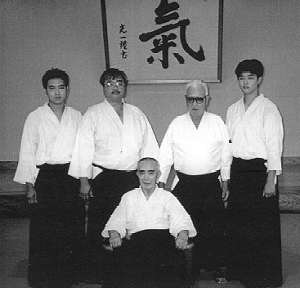

Front row, second from left: Takashi Nonaka. Center: Koichi Tohei. Far right: Eric Nonaka. 1976.

Mr. Nonaka retired from his job in 1986. During his 35 years at the laboratory he hired many people but never fired anyone, and the lab made lots of money. In the seven years following his retirement, the lab went through four managers and fired six people, including a manager. He attributes his success to using aikido principles in his dealings with people: he treated people with respect and let them make the day-to-day decisions, and in return they performed.

In 1992 Mr. Nonaka had both knees replaced. As a result, he can no longer sit seiza, which is the formal Japanese sitting position. At first he was depressed, but then he visited the therapy room at Queenís Hospital in Honolulu and saw people so much worse than himself that he figured he was doing just fine. He stayed with his aikido, too; now he just does his bowing from standing rather than kneeling positions. Some of his students say that his throws have improved, too. The reason, he thinks, is that since he canít use as much muscle, he now does a better job of blending form and mind. Nevertheless, following the second check-up Mr. Nonaka told his surgeon that if he needed another knee replacement, he wanted Japanese rather than American artificial knees. The Japanese didnít make artificial knees in 1992, so the doctor asked him what he meant. "American knees are only good for sitting in chairs," said Mr. Nonaka. "Japanese knees will surely be made for kneeling!"

In 1994 Mr. Nonaka was the subject of an interview published in a martial art magazine called Furyu. Actually this was a second interview, as Furyu editor Wayne Muromoto had interviewed Mr. Nonaka earlier for Hawaii Herald. As Muromoto had studied kendo and iaido in Japan for three years, he understood most of what Mr. Nonaka was trying to convey and as a result Mr. Nonaka thought that the interview came out well.

During August 2000 Mr. Nonaka attended the Ki Society International seminar in Japan with his son Eric and his grandsons Reid (shodan, 1998) and Brad (shodan, 2000). This was the first time that three generations of black belts had attended a Ki Society seminar, and everyone was impressed and treated them like kings. But it was somewhat embarrassing, too, because to his grandsons, Mr. Nonaka was just Grandpa, so of course they were always at his side, carrying bags, opening doors, and generally making him feel ancient.

From left to right, Reid Nonaka, Eric Nonaka, Koichi Tohei, Takashi Nonaka, Brad Nonaka. The occasion was a Ki Society International seminar in Japan commemorating Tohei Senseiís 80th birthday.

While in Japan, the Nonakas attended classes taught by Tohei Sensei.

Tohei Sensei retired from active instruction in 1990 and had a slight stroke

a few years later, so these days he teaches while seated in a chair. But

his mind is as active as ever, and he can see (and correct) improper energy

and center from across the room. It is amazing to see. "He reminds us to

relax," says Mr. Nonaka.

For Further Reading

"Aikido in Hawaii," http://id.mind.net/~aiki/history/aikido_history.htm

Hainline, Forrest, with Mark Matloff. "An Interview with Clyde Takeguchi Sensei," Aikido Today, May/June 2000, http://www.capitalaikikai.org/interviewATMlist.html

"Interview with Curtis Sensei," http://brugere.aub.dk/~rasmush/dvs/curtis_interview.htm

Muromoto, Wayne. "Flow Like a River: Takashi Nonaka and the Hilo Ki-Aikido Club," Furyu 4, http://www.furyu.com/archives/issue4/nonaka.html

Pranin, Stanley. "Aikido News Encyclopedia of Aikido," http://www.aikidojournal.com/reference/encyclopedia/index.htm

"Shinichi Suzuki, Maui Chief Instructor," http://www.maui.net/~cdc/kokyu/Suzuki.html

Tohei, Koichi. Ki in Daily Life (Tokyo: Ki No Kenkyukai HQ, 1990);

see also http://www.aikido2000.com/features/Interviews/ai_Interview_Master%20Koichi%20Tohei.htm

Editorís Notes

EN1. Ueshiba moved to Hokkaido in 1912, but according to Stanley Praninís research he did not meet Takeda until February 1915. And, while Ueshiba attended several 10-day seminars between 1915 and 1919, he was never Takedaís live-in student in Hokkaido. However, from April to September 1922 Takeda invited himself and his family to Ueshibaís house, and so for six months he certainly was Ueshibaís live-in teacher. See Stanley Pranin, "Morihei Ueshiba and Sokaku Takeda," Aiki News, 94 (Winter/Spring 1993), http://omlc.ogi.edu/aikido/talk/osensei/bio/mori1.html.

EN2. Kashiwaya currently lives in Seattle, where his dojo is at 6106 Roosevelt Way NE. For an online biography, see http://ki-aikido.net/KASHIWAYA/Bio.html.

EN3. At age sixteen, Saburo Nakamura (1879-1969; Tempu was an adopted name) joined the Japanese secret service and subsequently spent several years in Mongolia. Following the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905 he went to New York, where he received a degree from Columbia University in 1910. From the United States, he went first to Europe and then India, and in the latter country he studied yoga for three years. Upon returning to Japan, Nakamura entered business, but in 1919 he gave that up to become a lecturer. An advocate of world peace, Nakamura spent World War II under house arrest. The influence of Nakamuraís philosophy on Ki Society aikido is apparent in the following words, which were written by Tohei Sensei on the occasion of his eightieth birthday celebrations in 2000:

ĎBreathe out to the end of the universe and breathe in to the infinitely small point in the lower abdomen.í The true health method is to unify mind and body, which are given by the universe, and to fill the body with the ki of the universe. This is also the basic definition of Breathing Exercise.