By Joseph R. Svinth

An earlier version of this paper appeared in Occasional Papers,

A Publication of the Korean American Historical Society, 4 (1998-1999),

111-132. Copyright © Joseph R. Svinth 2001. All rights reserved.

Introduction

From 1910 to 1945, Japan ruled Korea, and from 1919 until 1945, the Imperial Japanese government did its best to fit the Korean people into a Japanese mold. Because many Japanese viewed Koreans as inferior, part of this molding process involved introducing "character-building" sports into Korean public schools and universities. Koreans excelled at the new games, and by the 1930s some of Japan’s finest athletes were ethnically Korean. For example, Kitei Sun (Ki Jung Sohn) established a world record in the marathon in 1935 and won Olympic gold in 1936. [EN1] In October 1938, a fifth-degree black belt named Senkichi Ri won a national judo championship in Tokyo. In October 1939, a freestyle wrestler named Kin took second in the welterweight division of an international competition held in Tokyo. And in October 1940, three Koreans -- Juitsu Nan, Seiichi Kin, and Turitsu Boku -- set world weightlifting records.

From the mid-1920s, Koreans also took up American-style gloved boxing, and again they excelled. Korean amateur boxers earned berths on Imperial Japanese squads participating in the Far Eastern Championship Games and the Berlin Olympics, and during the mid-1930s the Korean Teiken Jo was arguably Japan’s best professional boxer. [EN2]

Because Korea was a colony of Japan from 1910 until 1945, Korean boxing of the period 1926-1945 is best understood as part of the history of Japanese boxing. [EN3] Since amateur and professional boxers were recruited and trained differently, they need to be examined separately. Conclusions are presented at the end of the paper.

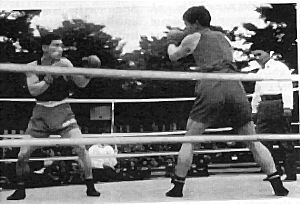

A member of Chuo University’s boxing team in the ring against a student

from Hosei, ca. 1936. From Arthur E. Grix, Japans Sport in Bild und

Wort (Berlin: Wilhelm Limpert, 1937).

Amateur Boxing

Although there was professional boxing in Japan as early as June 1887, the amateur game did not make much headway until 1923. During the 1920s, patrons included the Japanese Army, various universities, and Yujiro Watanabe of the Japan Boxing Club. [EN4] Originally Japanese amateurs fought according to rules similar to those used in US professional boxing, the chief exception being that the goal of the amateur game was scoring points rather than knockouts. Additionally, Japanese amateur matches:

Unfortunately, this bloodless style of fighting did not attract paying customers. As Arthur Suzuki of the Japanese-American Courier put it on March 25, 1933:

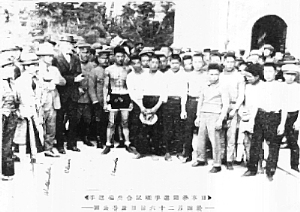

Captain Warren J. Clear, US Army, with Japanese boxers. To Clear’s left is Yujiro Watanabe, while the boxer in the center is Kintaro Usuda. Clear pioneered boxing at the Toyama Military Academy during the 1923-1924 season. Photo courtesy John Thompson.

Although relatively few Koreans attended Japanese colleges and universities during the 1930s, surprising numbers of those who did turned out for the boxing teams. I suspect that one reason was that the Koreans wanted to earn letters in some "manly" varsity sport, but feared discrimination from right-wing Japanese in judo or kendo classes. [EN5] Another reason was of course that every boy of the 1930s wanted to fight like the cowboys and gangsters he saw on the big silver screen. [EN6] Finally, many Koreans had previous experience with head-banging athletic games. While the Japanese called Korean traditional games old-fashioned, they couldn’t say anything bad about an Army-approved sport such as boxing.

Evangelical Christianity also played a role. From the 1870s until the 1930s, the philosophy called "Muscular Christianity" was quite popular in the English-speaking world, and the YMCA, which opened a gym in Tokyo in 1917 and in Seoul soon after, was a leader in this movement. Although basketball, volleyball, and swimming were the chief attractions in most YMCA gyms, boxing and wrestling were also popular with muscular Christians of the 1920s. [EN7]

The Keijo Imperial University YMCA was no exception to this generalization. Established in Seoul in 1926, Keijo Imperial University, the future Seoul National, was a notorious hotbed of anti-Japanese politics and activity. Now, I have no idea whether this radicalism bled over into the university boxing program. However, at the level of the individual boxers, probably it didn’t. For one thing, the boxers were all quite young. (Most Japanese professional boxers were 17-22 years old, and Korean amateurs were frequently even younger.) For another thing, had their politics been radical, then the youths would have spent more time in jail than in the gym. Finally, socialist organizations of the period generally encouraged members to participate in traditional wrestling styles rather than consumer-oriented Western spectator sports. So probably most of these early Korean boxers were simply tough kids who liked (or learned to like) fighting with their fists. [EN8]

In 1934, the Keijo Imperial University boxing coach was Yeijutsu Kin. Coach Kin was good, too, as his teams did unusually well during tournaments. For example, in October 1933, a Keijo team defeated two Japanese collegiate teams and tied a third. In September 1935, another Keijo team defeated a mostly Russian team at Dairen. And in November 1939 a Keijo team defeated a team from California’s San Jose State University. According to the Japan Times, fight fans considered the Koreans to be clean fighters, and much better sportsmen than the average Japanese professional.

Koreans boxed for Japanese colleges, too. For example, in 1936 the five-man Chuo University varsity boasted two members surnamed Ri while the rival Hosei University varsity included a Ri and a Kin. In 1937, three of the ten semi-finalists in an Osaka tournament had Korean surnames. In 1938, Waseda University’s Ri defeated Meiji University’s Kin, and in 1939, members of an All-Japan team that beat San Jose State University team included Sensho University’s Kisho Ri, Nihon University’s Heigoku Kin, Rikkyo University’s Ginshaku Ko, and Waseda University’s Keikan Ri. In fact, the only member of this All-Kanto squad to bear a Japanese surname was Katsuye Mori!

A few Korean amateurs boxed in overseas competition. For example, Keijo’s Shoba Kin and Ryushin Boku comprised half the Japanese squad during Manila’s Far Eastern Championship Games of 1934. In December 1934, Boku won the All-Japan featherweight crown, and in February 1935 he returned to Manila to win bouts against members of the José Rizal University team. Additionally, Keikan Ri, who started at Keijo and then went to Waseda, boxed for Japan in the 1936 Olympics.

A Korean also has the dubious distinction of being Japan’s first known amateur ring fatality. According to the Japan Times of November 16, 1940:

Professional Boxing

In June 1887, Shokichi Hamada staged a boxing exhibition between two Westerners in Tokyo, and from the 1890s until the 1920s, a kind of boxing versus jujutsu known as "Merikan" [American] was seen across the Pacific Rim. In 1922, a former US naval boxer named Harvey "Heinie" Miller described a typical "Merikan" bout staged in Manila circa 1909. [EN10]

The gong rang. Quicker’n you can say ‘Sap,’ the Jap grabbed ye scribe by the right arm, twisted and pitched us on our ear in a neutral corner some fifteen feet away. One fall for the Jap. After we got the resin well out of our ear we arose only to find the little brown brother right on top of us again. But this time we beat him to it with a sweet right hand, inside and up. The little rascal only weighed 98 pounds while we displaced some 124 at that time. So we take no credit for the fact that the gent from [Tokyo] folded his tent like an Arab and silently stole out of the ring. He forfeited the third trip to the canvas, explaining that he did not expect to get hit, being under the impression that the gloves were only used as a handicap for the difference in weight.

At any rate, the advent of professional boxing in Japan is generally dated to February 1921, and the establishment of the Japan Boxing Club in Tokyo. While announcing the creation of this organization, gym manager Yujiro Watanabe told the Japan Times that his purpose was "to teach boxing to those interested in building up, scientifically, good health and a perfect physique." Furthermore, to distinguish this "scientific bodybuilding" from "Merikan," Watanabe called the sport kunto, or "good fighting." His less famous contemporaries included Kenji Kano (a relative of Jigoro Kano) and "Young Togo" Koriyama, both of whom lived in Kobe.

Watanabe organized his first major card in May 1922. This match was held in Tokyo, and besides Watanabe, participants included three Americans that the California promoter James J. "Moose" Taussig had brought to Japan. To continue generating interest in boxing, Watanabe imported a number of European and Filipino fighters in 1923, accompanied the Japanese Olympic team in 1924, and even took four fighters to California in 1926.

Moose Taussig with Japanese fighters in San Francisco, ca. 1926-27; the arrow points to Taussig. Photo courtesy Patrick Fukuda.

During the early 1920s, Watanabe also organized the Japan Boxing Association. This was essentially a guild, and to belong, gym owners first had to pay ¥20,000 in membership fees. Twenty thousand yen was then worth about US $9,400, and to put this sum in perspective, in East Asia of the 1920s, one could buy a stud horse for ¥70,000, a trained pointer bitch for ¥300, and a Chinese slave girl for ¥30. So, to recoup this enormous investment, promoters had to develop boxers that crowds were willing to pay money to see. Since the fans stayed away from the refined amateur style in droves, Watanabe and the other promoters told prospective boxers that it was their duty to treat the fans to a knockout. And, wanting to please, these earnest young men soon adopted a system of fighting that almost guaranteed somebody getting knocked out. Known as the "piston attack," after the piston-like way that the boxer’s arms kept hammering the opponent without giving any thought to defense, it wasn’t boxing, but it did satisfy fans who, in the words of Japan Times (Jan. 15, 1925) wanted to see boxers "rush madly against each other from the start, punching mechanically and make a quick end of the bout." [EN13]

In return for their efforts, Japanese club fighters were promised a regular salary. From a Japanese standpoint, this method had several advantages over the American system, where fighters received a percentage of the gate. First, as early Japanese gates were small, a percentage wouldn’t have paid much. Second, the method reduced the individual boxer’s risk of being cheated by unscrupulous promoters. Third, the base wages, which averaged between ¥25 and ¥50 per month, weren’t bad, especially as Korean day laborers only earned ¥1.2 per day anyway. And of course most importantly, salaried boxers could always dream of becoming famous champions earning a princely ¥300 per month. Unfortunately, there is reason to believe that promoters expected boxers to pay their own living and training expenses, plus reimburse them for what amounted to indenturing fees. If so, then many, perhaps most, boxers would have been deep in debt upon reaching the end of their careers. [EN14]

At least in English, details of how pre-Pacific War Korean and Japanese boxers trained for their matches are scarce. An exception is the following statement by Alfred E. Pieres that appeared in the Japan Times on April 16, 1925:

In the US, boxers used to attribute great powers to red meat, but Koreans probably ate more ginseng, garlic, and kimchee. Injury treatment was probably different, too. For example, the Koreans of the 1980s drank barley tea as an energizer and used powders made of crushed chrysanthemum roots to treat headaches. So perhaps the Imperial boxers of the 1930s did as well. [EN15]

Ideologically, the emphasis on the piston attack suggests that Japanese martial culture may have influenced Imperial Japanese boxing. After all, bushido, the Way of the Warrior, was a popular concept in Japan during the 1920s and 1930s, and Young Togo Koriyama taught kendo and judo as well as boxing at his Mikage gym. Nevertheless, jingoism knows no boundaries, and in the January 1923 issue of The Ring, Nat Fleischer stated as fact that it was boxing that had "led America on to victory amid the shambles of the Marne and Chateau-Thierry!" So perhaps it would be equally correct to say that parents everywhere wanted manly sons, boys everywhere wanted Jack Dempsey’s tremendous punching power (and income), and promoters everywhere used whatever vocabulary sold the most tickets.

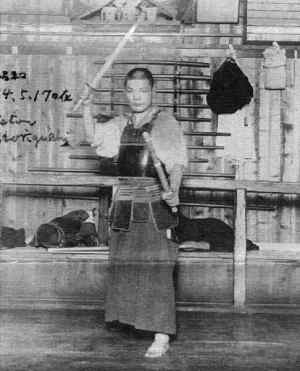

That said, Japanese sometimes took this emphasis on "the spirit of manliness" to extremes. For example, during 1938 the featherweight champion Tsuneo "Piston" Horiguchi suffered from jaundice, and as a result, he started losing speed in his punches. Rather than treating his illness, his trainers told him that his problem was that he lacked sufficient Yamato damashii, or "Japanese spirit," and toward restoring this spirit in their fighter, the trainers then had Horiguchi practice kendo and karate.

Piston Horiguchi practicing kendo ca. 1938. Photo courtesy Dragon

Times.

Korean Professional Boxers

By the 1930s, there was a circuit for Japanese boxers. I do not know its full extent, but main event locations included Tokyo, Manila, and Shanghai, while whistle stops included Dairen, Kobe, Kyoto, Osaka, Seoul, and Yokohama. During the 1930s, several Hawaiian fighters reported being threatened by gangsters while boxing in Japan, so the Japanese gambling syndicates were clearly involved. And, as Japan’s prewar gambling syndicates frequently cooperated with the Japanese secret police, the circuit perhaps served a secondary intelligence gathering function. Reliable information with which to support or refute such conjectures is, however, unsurprisingly lacking. [EN16]

Be that as it may, Ryushoku Ri was the first Korean to become a prominent professional boxer in Japan. Born in Korea on June 11, 1908, Ri started boxing in Shanghai during the late 1920s. His ring name there was "Young Ambition." He relocated to Tokyo in February 1931, and like many Koreans of the day, he changed his name to avoid discrimination. The name chosen was Tetsuro Uemura.

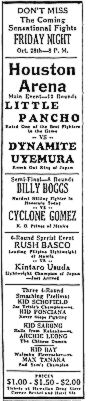

Following a lackluster showing in Tokyo, Ri took a trip to Hawaii. While his most important fight was probably his ten-round loss to Eulogio "Little Pancho" Tingson on October 28, 1932, he also had a six-round loss to Henry Callejo on December 10, 1932. Ri’s manager in Hawaii was a Japanese national named J.I. Fukuoka.

Newspaper advertisement for Uemura’s fight with Little Pancho.

Although a fit and aggressive fighter, Ri’s record suggests that he lost nearly as often as he won. Biased officiating may have had something to do with this, as on April 29, 1931, a Hawaiian Nisei named Leslie Nakashima described Japanese referees as "somewhat pitiful, especially during the preliminary during the course of which a man was permitted to punch at his opponent while he was sitting on the canvas." Mostly, though, his problem seems to have been too much reliance on wild right swings, the kind so beloved by Hollywood film stars.

Following his loss to Piston Horiguchi in September 1933, Ri retired to Korea. I have no idea what happened to him after that.

Teiken Jo was another Korean who boxed in Japan during the early 1930s. Born in Korea around 1913, Jo went to Tokyo around 1930, apparently for the purpose of studying at Meiji University. While in Japan, he took up professional boxing, reportedly to help his family put his two younger brothers through high school.

Jo’s pro debut took place in Tokyo on April 16, 1931. Despite giving up ten pounds to many opponents, the 117-pounder lost none of his first nineteen professional fights, and his six-round victory over Young Pancho Villa (Luis Camposeno) on November 6, 1931 was the highlight of the second professional boxing card ever broadcast over Japanese radio.

But, as the Japanese were not enthusiastic about having a Korean champion, in April 1932 Jo went to California, where boxers were said to earn enormous sums. Sadly, though, he never made Dempsey’s millions. Instead, he probably grossed no more than $15,000. (According to the Los Angeles Times for December 17, 1934, Jo had nine bouts in Hollywood that year for which he earned a total of $4,359.) Furthermore, North American managers and trainers typically took 30-60 percent of a boxer’s purse, and also expected the boxers to pay all taxes and travel and training expenses. Finally, Jo was a man known to enjoy gambling. As a result, he probably left the US as broke as he came. [EN17]

Teiken Jo with manager Frank Tabor, ca. 1933. The inscription reads, "To my pal, Johnny Yasui, from Jo Teiken." From the Johnny Yasui Collection, courtesy Curtis Narimatsu.

Nevertheless Jo was always optimistic about his future, and on August 19, 1933, the Japanese-American Courier quoted the wife of Hollywood matchmaker Charlie McDonald saying this about the man: "I was first attracted by his shy and modest mannerism. He was extremely polite and although unable to speak but very little English, I could see that he had culture and education. I was pleasantly surprised to hear that he was a university graduate in [Tokyo] and was sending his two brothers through the same school."

Jo had his chances, though, and on May 22, 1933 he even got a crack at the California title held by the Filipino bantamweight Diosdado "Speedy Dado" Posadas. Living up to his reputation, Posadas won the first six rounds on speed alone, and in the third, Posadas started a cut to Jo’s left eye that eventually caused it to swell shut. But in those days they didn’t call professional fights for mere bleeding and by the eighth Posadas, whose training for the fight had included considerable partying, was starting to tire. So, in desperation, during the ninth Posadas landed a low blow that under California rules should have caused the match to be awarded to Jo on a foul. However, the Korean was too proud to win sitting down, and so he stood back up to finish the fight. As a result, Posadas won the judges’ decision and thereby retained his title.

In October 1934 Jo participated in a Canadian elimination tournament designed to fill the recently vacated world bantamweight title. Following some trouble getting through Canadian immigrations (his work permit did not extend to Canada), he boxed Carlos "Baby" Quintana in Montreal on November 7, 1934. Although Quintana won the bout by unanimous decision, the following day a sportswriter for the Montreal Gazette wrote that the local promoter "could do worse than match the little Korean on another of his cards... He never stopped throwing punches last night." But by November 1934 Jo’s future was already past. As John Fujii had written in the Japan-California Daily only four months before:

Umio Gen was another Korean who fought in Japan and North America during the 1930s. Born in Korea in 1919, Gen moved to Tokyo at the age of eleven. An industrious young man, he worked by day and went to school at night. And, although he had an unusually witty mind and was good looking, Los Angeles reporter Joe Ishikawa said that Gen had no girlfriends because, "to use his own words, he is going to grow up to be a ‘bachera’ [bachelor]." [EN18]

In November 1935, the 16-year old Gen entered the All-Japan Pro Boxing Championships. Fighting for the Imperial Boxing Club and weighing about 117 pounds, in his debut he earned a four-round decision over the experienced Yukiichi Masumura. Gen continued his winning ways, and in December 1935 he surprised the pundits by winning the Japanese bantamweight title. Unfortunately his jab was weak and his straight right (the overhand punch that most sportswriters call a cross) wasn’t much stronger. So during the summer of 1936 he lost fights to harder-hitting Filipino fighters in Manila, and in September 1936 he lost the Japanese bantamweight title to Seiichi Otsu.

Hoping to improve his skills, Gen went to the United States in August 1937. Although he fought at least seventeen times over the next eighteen months, he does not seem to have won a single fight. However, his list of opponents reads like a Who’s Who of top bantamweights, and so this result is not as awful as it sounds. Indeed, better managed, Gen might have been, in Bud Schulberg’s immortal phrase, a contender. Be that as it may, both promoters and fans adored him. The reason was that no matter how hard the other fellow hit him, Gen kept boring in, fists pumping like pistons. "Many a time Gen was hit hard," said the North American Times said following his loss to Frankie Lembo in Hollywood on February 1, 1938, but "his speed and stamina … carried him through to an excellent finish."

Such crowd-pleasing courage carries a price, of course, and studies have shown that a boxer’s risk of brain and eye injury correlates directly to the number of rounds fought. [EN19] Gen did not beat the odds, and on August 6, 1938, Bill Hosokawa of Seattle’s Japanese-American Courier had this to say about the nineteen-year old Korean:

His name is Umio Gen, the boxer, as willing a fighter as has ever been seen in a Seattle ring. A few months ago, he didn’t need those glasses. And injured optics or no, Gen is signed to go in the ring again on August 9 in Stockton.

The game which has no place for those who can’t stand the pace, needs them to make fodder for some younger fighter testing his fists in his upward climb. The willing boys without the ability are the stepping stones.

Gen returned to Japan in early 1939, and soon after his arrival he fought (and beat) Piston Horiguchi. In January 1940 the two men had a rematch and, while Gen’s footwork still impressed everyone, Horiguchi won this second fight on points. Two months later, on March 7, 1940, Gen lost a ten-round decision to Susumu Tokunaga. Gen’s timing in this fight, said Japan Times, "was something terrible." So probably he was in serious physical decline. Nevertheless, his last two known fights, both in April 1940, ended with wins by knockout.

As with Jo, I do not know what happened to Gen after he retired from the ring.

One final Korean who gained significant reputation as a professional boxer before World War II was Ryushin Boku. After leaving college, Boku joined Yujiro Watanabe’s Japan Boxing Club and during his pro debut in July 1937 he earned a four-round decision over Kikuji Minakawa. Boku continued to win his bouts, and by March 1939 he was fighting main events throughout the Japanese Empire.

Boku won two important victories before the Pacific War put a damper

on Japanese professional boxing for the duration. [EN20]

The first was on October 10, 1939, when, despite a 17-pound weight disadvantage,

he defeated the former Japanese welterweight champion Matsuo Amino. The

second was on October 12, 1940, when he defeated Piston Horiguchi to become

the undisputed featherweight champion of Japan. Nevertheless, Boku was

never a popular champion. The reason was that he rarely used the piston-style

offense or pursued an unnecessary knockout, and was therefore perceived

as lacking fighting spirit.

Conclusions

Since boxing only became popular in Japan in the early 1920s, its introduction into Korea probably dates to the same era, or perhaps a few years later. Unlike Japanese, Koreans took to the sport quickly, and by the early 1930s Koreans were leading members of Japanese collegiate and international boxing teams. Indeed, the Koreans sometimes comprised as much as five-sixths of those Japanese teams. Probably this had to do with ethnically Japanese athletes preferring more glamorous sports, thus leaving the boxing to lower-status Koreans.

Koreans also boxed professionally. Well-known Korean professionals included:

Due to my reliance on English-language sources, the economic, political, and social histories presented in this paper are often speculative and rarely presented in any detail. That said, the following patterns emerged.

Imperial Japanese (ergo, Korean) boxing placed more emphasis on courage and endurance (ganbare) than ring generalship. Professional boxers received minimal training, and the few techniques they did learn emphasized the crowd-pleasing "piston" offense. Unsurprisingly, professional careers were short – in June 1933, Japan Times said five years was about average -- and when the fighters were through, they were often physical wrecks.

Although English-language documentation of Japanese boxing injuries is poor, Japanese and Korean amateur boxers probably suffered fewer long-term injuries than did Japanese and Korean boxers. The reasons included shorter rounds, different rules, and heavier gloves. Nevertheless, Japan’s first known amateur boxing fatality involved a Korean. So what happened to the professionals? Evidently they got lucky – Japan’s only known boxing fatality before the Pacific War was Nobuo Kobayashi, who died following a fight with the Filipino Bobby Wills in August 1930.

No pre-World War II Korean boxer appears to have made (or at least retained) much money. Although boxers grossed more than day laborers, by the time promoters’ fees were taken out, their net was similar. Thus many, perhaps most, boxers would have been in debt upon reaching the end of their careers. Boxing in the United States was not any more lucrative, the American promoters simply took their share in different ways.

Both Koreans and Japanese believed that boxing developed gaman, or perseverance. A secondary trait attributed to boxing was Yamato damashii, the spirit that supposedly inspired people of Japanese ethnicity to ignore all obstacles in their quest to accomplish their missions. An interesting phenomenon associated with this is the fact that Japanese fans preferred boxers who lost bravely to boxers who won inelegantly: fighting spirit meant that one strived one’s utmost.

Finally, Korean independence from Japan following World War II does not seem to have had much effect on the way that individual Korean boxers fought. Witness, for example, this July 1948 Ring description of a bout between Hawaii’s Robert Takeshita and Korea’s Bok-Soo Chung:

The fight was a sensational one all the way. Soo rushed out from his corner like a mad bull and started slugging it out at close quarters with Takeshita. For six rounds Soo fought at this fast pace, taking a terrific beating but without yielding an inch of ground. Though the aggressor all the way, Soo, nevertheless, fought a losing battle as he took three or four punches before landing one of his own…

Appendix 1: Career Summary of Jo Teiken

The Japanese track boxing statistics ethnically rather than geographically. Thus they claim a Japanese who died in Guam as a Japanese ring fatality, but do not count two Koreans who died in Tokyo. As a result, Japanese sources frequently list Tsuneo "Piston" Horiguchi as Japan’s greatest prewar boxer – which, ethnically speaking, he probably was. Nonetheless, inasmuch as Korea was then part of Imperial Japan, I’m willing to argue that Jo was Japan’s best pre-Pacific War boxer.

My reasoning is this. Although I’m undoubtedly missing fights, my research shows Jo having 77 fights during his career -- 40 wins, 14 draws, and 23 losses. Many of these losses were to first-rate fighters in their prime, and as a result The Ring ranked Jo sixth in the world in January 1934, as did Everlast Ring Record in 1935. Meanwhile, I show Horiguchi having 61 fights -- 50 wins, 7 draws, and 4 losses. While an impressive record, Horiguchi rarely achieved better than a draw when fighting well-regarded foreign fighters. Furthermore, while visiting Hawaii in 1936, the best Horiguchi could do was two wins and three draws, and one of the wins was disputed. Finally, after losing to everyone in America, Umio Gen beat Horiguchi without too much trouble in 1939. As a result, I suggest that Jo was a better boxer than Horiguchi. Jo’s rating appears in Ring, January 1934, 51 and Everlast Boxing Record (New York: Everlast Sports Publishing Co., 1935), 131. A fuller assessment of Horiguchi’s career appears in Joseph R. Svinth, "The Exemplar of the Piston Attack: The Imperial Japanese Boxer Tsuneo Horiguchi," 2000, Journal of Combative Sport, http://ejmas.com/jcs/jcsart_svinth1_0200.htm.

Jo’s manager in California was Frank Tabor. Ring Record Book 1944

says that he served in the US Army during WWII, but this is probably an

error. He stood 5’2", and weighed between 120 and 130 pounds.

| Date | Opponent | Venue | Result |

| 1931 Apr 16 | Goro Kashiwamura | Tokyo | KO1 |

| 1931 May 3 | Isamu Ito | Tokyo | W8 |

| 1931 May 23 | Isamu Ito | Tokyo | D8 |

| 1931 Jun 10 | Iwao Kondo | Tokyo | W8 |

| 1931 Jun 18 | Isamu Ito | Tokyo | D8 |

| 1931 Jul 4 | Johnny O'Donnell | Tokyo | W8 |

| 1931 Jul 24 | Goro Kashiwamura | Tokyo | W6 |

| 1931 Sep 16 | Yasu Hara | Tokyo | W10 |

| 1931 Sep 25 | Ryushoku Ri ("Tetsuro Uemura") | Tokyo | TKO5 |

| 1931 Nov 6 | Lou B. Camposano ("Young Pancho Villa") | Tokyo | W6 |

| 1931 Nov 12 | Tadato "K.O." Kuratsu | Tokyo | W10 |

| 1931 Nov 26 | Alfredo "Freddy" Imperial | Tokyo | D10 |

| 1931 Dec 12 | Ryushoku Ri ("Tetsuro Uemura") | Tokyo | W10 |

| 1931 Dec 19 | Kentaro Kobayashi | Tokyo | W6 |

| 1932 Jan 8 | Alfredo "Freddy" Imperial | Tokyo | D6 |

| 1932 Jan 15 | Isamu Ito | Tokyo | W6 |

| 1932 Mar 22 | Mike Luizza | Tokyo | D8 |

| 1932 Apr 2 | Mike Luizza | Tokyo | W6 |

| 1932 Apr 16 | Goro Takata | Tokyo | TKO3 |

| 1932 May 27 | Jack Cavanaugh | San Francisco | W4 |

| 1932 Jun 3 | Vic Perez | San Francisco | TKO1 |

| 1932 Jun 13 | Mike Luizza | San Francisco | TKO2 |

| 1932 Jun 22 | Tuffy Pierpont | San Francisco | KO2 |

| 1932 Jul 2 | Eulogio Tingson ("Little Pancho") | Sacramento | D10 |

| 1932 Jul 25 | Star Frisco | Los Angeles | W10 |

| 1932 Aug 11 | Fernando Opao ("Young Tommy") | Sacramento | L10 |

| 1932 Oct 6 | Billy McLeod | Stockton | D10 |

| 1932 Oct 19 | Eddie Gevesole | Oakland | W6 |

| 1933 Jan 13 | Eugene Huat | Hollywood | W10 |

| 1933 Jan 26 | Fernando Opao ("Young Tommy") | Hollywood | L10 |

| 1933 Feb 17 | Mike Luizza | Stockton | D10 |

| 1933 Feb 17 | Augie Curtis | Hollywood | TKO2 |

| 1933 Mar 3 | Fernando Opao ("Young Tommy") | San Francisco | L10 |

| 1933 Mar 22 | Hubert "Baby" Palmore | Oakland | W10 |

| 1933 Mar 29 | Eulogio Tingson ("Little Pancho") | Oakland | L10 |

| 1933 Apr 7 | Harry Fierro | Hollywood | KO8 |

| 1933 Apr 21 | Cris Peneda | Hollywood | W10 |

| 1933 Apr 28 | Star Frisco | San Diego | W10 |

| 1933 May 22 | Diosdado Posadas ("Speedy Dado") | Hollywood | L10 |

| 1933 May 24 | Frankie Nour | San Francisco | KO3 |

| 1933 Jun 16 | Cris Peneda | Hollywood | W10 |

| 1933 Jul 4 | Felix Ignacio | Pismo Beach | TKO10 |

| 1933 Jul 14 | Diosdado Posadas ("Speedy Dado") | Hollywood | L10 |

| 1933 Aug 4 | Billy McLeod | Hollywood | D10 |

| 1933 Aug 11 | Star Frisco | Hollywood | LF9 |

| 1933 Sep 4 | Eulogio Tingson ("Little Pancho") | Pismo Beach | W10 |

| 1933 Oct 31 | Star Frisco | Portland, OR | L10 |

| 1933 Nov 22 | Lew Farber | San Francisco | W10 |

| 1933 Nov 30 | Chato Laredo | Pismo Beach | W10 |

| 1934 Jan 1 | Pablo Dano | Pismo Beach | L10 |

| 1934 Feb 9 | Eulogio Tingson ("Little Pancho") | Oakland | L10 |

| 1934 Feb 22 | Benjamin Gan ("Small Montana") | Pismo Beach | W10 |

| 1934 Mar 31 | Babe Triscaro | Hollywood | W10 |

| 1934 May 4 | Benjamin Gan ("Small Montana") | Pismo Beach | W10 |

| 1934 May 29 | Matty Matheson | San Jose | D10 |

| 1934 Jun 15 | Fernando Opao ("Young Tommy") | Hollywood | D10 |

| 1934 Jul 13 | Fernando Opao ("Young Tommy") | Hollywood | D10 |

| 1934 Aug 10 | Lou Salica | Hollywood | L10 |

| 1934 Sep 21 | Diosdado Posadas ("Speedy Dado") | San Francisco | TKO3 |

| 1934 Sep 28 | Diosdado Posadas ("Speedy Dado") | San Francisco | L10 |

| 1934 Nov 8 | Carlos "Baby" Quintana | Montreal | L10 |

| 1934 Nov 30 | Carlos "Baby" Quintana | New York City | L8 |

| 1934 Dec 4 | Dick Li Brandi | New York City | W8 |

| 1935 Jan 11 | Charles Zeletes | Barrington, NJ | KO5 |

| 1935 Feb 22 | Fernando Opao ("Young Tommy") | Hollywood | W10 |

| 1935 Mar 8 | Benjamin Gan ("Small Montana") | Sacramento | L10 |

| 1935 May 24 | Benjamin Gan ("Small Montana") | San Francisco | L10 |

| 1935 Jun 14 | Fernando Opao ("Young Tommy") | Watsonville | L10 |

| 1935 Jul 4 | General Padilla | Pismo Beach | D10 |

| 1935 Jul 13 | Pablo Dano | Watsonville | TKO by 5 |

| 1935 Sep 7 | Cris Peneda | Tokyo | L10 |

| 1935 Oct 21 | Rush Joe | Tokyo | TKO6 |

| 1936 Feb 20 | Sai Seki | Tokyo | L10 |

| 1937 Jan 4 | Tsuneo "Piston" Horiguchi | Tokyo | TKO by 4 |

| 1937 Feb 26 | Iwao Kongo | Tokyo | L8 |

Appendix 2: Career Summary of Umio Gen

Umio Gen had courage and good footwork, but little power in his punches. As a result, he had a disappointing career: 14 wins (four by KO, all in Asia), 5 draws, and 21 losses (two by KO). In fairness, though, it must be pointed out that Gen was mismanaged, as in the United States he was immediately put up against the very best featherweights in the world. Nonetheless, he went the distance with all but two, and one of those knockouts came just three days after a ten-round defeat! So, to put it bluntly, he was thrown to the wolves.

His manager in the United States was Jesus "Jes" Cortez.

| Date | Opponent | Venue | Result |

| 1935 Mar 26 | H. Aoki | Tokyo | D4 |

| 1935 Nov 11 | Yukiichi Masumura | Tokyo | W4 |

| 1935 Nov 25 | Takeshi Makino | Tokyo | W6 |

| 1935 Dec 2 | Masahiro Nozaki | Tokyo | W6 |

| 1935 Dec 16 | Hitoshi Seki | Tokyo | W8 |

| 1936 Jan 5 | Seichi Otsu | Tokyo | W10 |

| 1936 Mar 24 | Saden Fujita | Tokyo | W8 |

| 1936 May 9 | Eulogio Tingson ("Little Pancho") | Manila | L10 |

| 1936 May 23 | Joe Mendiola | Manila | L10 |

| 1936 June 10 | Star Frisco | Manila | W10 |

| 1936 Sep 14 | Seichi Otsu | Tokyo | L12 |

| 1936 Sep 30 | Toshitaka Nagahara | Tokyo | TKO6 |

| 1936 Oct 6 | Kurazo Takami | Tokyo | TKO6 |

| 1936 Dec 1 | Joe Eagle | Tokyo | L10 |

| 1937 Mar 7 | Jitsukazu Koike | Tokyo | W12 |

| 1937 Jul 2 | Tusneo "Piston" Horiguchi | Tokyo | L12 |

| 1937 Aug 8 | Joe Eagle | Tokyo | W10 |

| 1937 | Tomboy Romero | Stockton | L10 |

| 1937 Sep 25 | Pablo Dano | Hollywood | L10 |

| 1937 Oct 5 | Pablo Dano | San Jose | L10 |

| 1937 Nov 2 | Ah Chu Mah | Hollywood | D10 |

| 1937 No v 9 | Richie Fontaine | Hollywood | L10 |

| 1937 Dec 14 | Billy Buxton | Seattle | D10 |

| 1938 Jan 21 | Nick Peters | Hollywood | L10 |

| 1938 Feb 1 | Frankie Lembo | Seattle | D10 |

| 1938 Mar 11 | Johnny Brown | Hollywood | L10 |

| 1938 Apr 1 | Tony Chavez | Hollywood | TKO by 6 |

| 1938 Jul 1 | George Latka | San Francisco | L10 |

| 1938 Aug 23 | Tomboy Romero | Stockton | L10 |

| 1938 Aug 26 | David Kui Kong Young | San Francisco | KO by 2 |

| 1938 Sep 23 | Albert "Baby" Arizmendi | San Diego | L10 |

| 1938 Oct 26 | Kenny Reed | San Diego | L10 |

| 1938 Nov 22 | Pablo Dano | Cleveland | L10 |

| 1938 Dec 20 | Henry Hook | Cleveland | L10 |

| 1939 Jan 24 | Frankie Covelli | NYC | L10 |

| 1939 May 29 | Tsuneo "Piston" Horiguchi | Tokyo | W10 |

| 1940 Jan 5 | Tsuneo "Piston" Horiguchi | Tokyo | L12 |

| 1940 Mar 7 | Susumu Tokunaga | Tokyo | D10 |

| 1940 Apr 17 | Takeshi Kaido | Tokyo | KO6 |

| 1940 Apr 27 | Shintaro Yamada | Seoul | KO5 |

Appendix 3. Career Summaries of Other Fighters Mentioned in the Text

The other fighters mentioned in the text were Ryushoku Ri ("Tetsuro

Uemura") and Ryushin Boku. My tabulations of these men’s bouts are spotty,

and as a result my conclusions may be based on false premises. Readers

with additional information are therefore requested to contact the author

at jsvinth@ejmas.com.

Ryushoku Ri ("Tetsuro Uemura")

Until February 1931, Ri fought in Shanghai, and I have no results of

his career there. In Japan, he probably also fought outside Tokyo. Be that

as it may, the following career summary of 9 wins, 2 draws, 5 losses, and

one unknown is less impressive than it sounds. The reason is that his opponents

were either kids on their way up or journeymen on their way down. Leslie

Nakashima of Japan Times was not much impressed with his technique,

either, which apparently consisted mostly of wild right swings that missed.

Therefore it is probably safe to conclude that there wasn’t much depth

to Japanese professional boxing during the early 1930s.

| Date | Opponent | Venue | Result |

| 1931 Feb 17 | Unknown | Tokyo | W |

| 1931 Jun 18 | Paul Cuneo | Tokyo | TKO1 |

| 1931 Sep 4 | Kaneo Nakamura | Tokyo | TKO2 |

| 1931 Sep 16 | Kazuo Takahashi | Tokyo | W10 |

| 1931 Sep 14 | Yasu Hara | Tokyo | D6 |

| 1931 Sep 25 | Teiken Jo | Tokyo | TKO by 5 |

| 1931 Oct 25 | Alfredo "Freddy" Imperial | Tokyo | D4 |

| 1931 Nov 4 | Alfredo "Freddy" Imperial | Tokyo | W6 |

| 1931 Nov 12 | Alfredo "Freddy" Imperial | Tokyo | W6 |

| 1931 Nov 28 | Battling Kuba | Tokyo | TKO7 |

| 1931 Dec 12 | Teiken Jo | Tokyo | L10 |

| 1931 Dec 19 | T. Noda | Tokyo | W |

| 1932 Jan 8 | Kaneo Nakamura | Tokyo | LTKO4 |

| 1932 Oct 28 | Eugelio Tingson ("Little Pancho") | Honolulu | L10 |

| 1932 Dec 10 | Henry Callejo | Wailuku | L6 |

| 1933 Mar 23 | Fighting Yabu | Tokyo | ? |

| 1933 Oct 3 | Tsuneo "Piston" Horiguchi | Tokyo | KO by 3 |

Ryushin Boku

As an amateur, Boku fought for both Keijo and Meiji Universities. As a professional, he fought for Watanabe’s Japan Boxing Club.

Based on his win/loss ratio, Boku was certainly one of Imperial Japan’s better boxers. However, he was never a crowd-pleaser, for according to Japan Times he did only what it took to win, and this ran contrary to the general belief that fighters owed the crowd a knockout.

Amateur

| Date | Opponent | Venue | Result |

| 1933 Oct 8 | Iwakura | Tokyo | L3 |

| 1933 Oct 15 | Katsuo Kameoka | Tokyo | L3 |

| 1933 Oct 20 | Unknown | Osaka | W3 |

| 1934 Mar 19 | Avalino Cunanan | Manila FECG | L3 |

| 1934 Dec 8 | Unknown | Tokyo | W3 |

| 1934 Dec 16 | Unknown | Tokyo | W4 |

| 1935 Feb 20 | Aricacil | Manila | TKO3 |

| 1935 Mar 3 | Avalino Cunanan | Manila | W3 |

| 1935 May | Unknown | Tokyo | ? |

| 1936 Apr 8 | Unknown | Tokyo | L3 |

| 1936 Sep | Unknown | Tokyo | ? |

| 1937 May | Unknown | Tokyo | W |

Professional

| Date | Opponent | Venue | Result |

| 1939 Mar 15 | Motoyama | Tokyo | W10 |

| 1939 Oct 10 | Matsuo Amino | Tokyo | W8 |

| 1940 Apr 26 | Kid Felipe | Tokyo | W8 |

| 1940 Aug | Paul Lojinkoff | Shanghai? | D10 |

| 1940 Sep 3 | Aoki | Tokyo | W8 |

| 1940 Sep 26 | Ichiro Mitsuyama | Tokyo | W10 |

| 1940 Oct 12 | Tsuneo "Piston"Horiguchi | Tokyo | W10 |

Acknowledgments

Funding sources for the research involved in writing this paper included the Japanese American National Museum, the King County Landmarks and Heritage Commission, and the Korean American Historical Society.

The assistance of the following individuals is also gratefully acknowledged: Pat Baptiste, Matthew Benuska, Janet Bradley, Patrick Fukuda, Charles Johnston, Richard Hayes, William K. Hosokawa, G. Cameron Hurst III, Paul Lou, Michael D. Machado, Eric Madis, Rod Masuoka, Curtis Narimatsu, Brian Niiya, Graham Noble, John Ochs, Charles Payton, Brian Sekiya, Robert W. Smith, Curtis Stanley, John Thompson, Wayne A. Wilson, Thomas Yamaoka, Luckett Davis and George "Horse" Yoshinaga.

Endnotes

EN1. In this paper, Korean and Japanese names have been put into the American name order of personal name, family name. This has been for consistency, something that did not exist in the sports pages of the 1930s. Also, inasmuch as Korea was then part of the Japanese Empire, the contemporary transliterations of Korean family names used here usually show considerable Japanese influence. For example, Jo should be Cho, Kin should be Kim, and Ri should be Lee. As for Boku and Gen, my best guess is that in Korean they are Park and Hyun.

EN2. Jo was known in the USA as Jo Teiken, with most Americans assuming Jo was his personal name rather than his family name. For that matter, Teiken may not be a personal name, but may instead refer to the Teiken Gym in Tokyo.

EN3. Although people with access to the records of the Korean Society for Physical Culture (the predecessor of the Korean Athletic Union) may quibble with 1926 as a starting date and 1945 as an ending date, I selected those dates for a number of reasons. First, they essentially coincide with that portion of Hirohito’s reign that the Japanese call early Showa. Second, Korea regained independence from Japan following World War II, which in turn means that after 1945 Korean sport history becomes separate from Japanese sport history. Third, Western-style gloved boxing only became popular in Japan after 1921. Therefore it seems unlikely that the sport would have been successfully introduced into Korea any sooner. Finally, Keijo Imperial University, an important center of pre-WWII Korean amateur boxing, was established in Seoul in 1926. So for all these reasons, 1926-1945 seemed a logical time frame.

EN4. Although it is traditional to date amateur boxing in Japan to the establishment of Yujiro Watanabe’s Japan Boxing Club in February 1921, that club was dedicated to professional rather than amateur boxing. Furthermore, the only major reference to amateur boxing that I saw in Japan Times between 1921 and 1923 was a photo published on July 23, 1923 that showed Watanabe teaching boxing to the American-educated actress Komako Tokunaga. Thus my saying that amateur boxing really dates to 1923, at which point Watanabe promoted a collegiate tournament and the Toyama Military Academy organized classes. For an introduction to Japanese military support for collegiate boxing, see Joseph R. Svinth, "Amateur Boxing in Pre-World War II Japan: The Military Connection," 2000, Journal of Non-Lethal Combatives, http://ejmas.com/jnc/jncart_svinth2_0100.htm.

EN5. For an example of the type of prejudice Koreans faced on Japanese high school judo teams, see Jim Yoshida with Bill Hosokawa, The Two Worlds of Jim Yoshida (New York: William Morrow, 1972), 55-58.

EN6. "American movies in which the hero knocks men right and left have taken an important part in the training of the Japanese mind for the reception of the savage Western boxing," Kari Yado wrote in Japan Times on February 21, 1931. Movies also influenced Korean minds. For example, Tang Soo Do karate teacher Haeng-ung Lee told Tae Kwon DoTimes (Mar. 1992, 33), "As kids [in Korea during the 1950s], we loved to watch them [film stars] fight, and all of us wanted to be able to fight better. I tried judo when I was nine or ten, but I couldn’t throw the big guy. Then I took up boxing and I got hit too much and got lots of headaches. I looked for something better and found Tang Soo Do."

EN7. Although the Tientsin YMCA introduced basketball to China in January 1896, I haven’t seen anything showing when the Seoul YMCA started a team. That said, Hyozo Omori introduced volleyball and basketball into the Tokyo YMCA in 1908, and on January 7, 1920, the Tokyo YMCA reported that its opponents included Kyoto, Shanghai, and Seoul. As for boxing, what missionaries and the clergy opposed was the gambling and drinking associated with prizefighting rather than pugilism itself, and before World War I, Philadelphia socialite A. J. Drexel Biddle was notorious for using boxing and boxers to illustrate Bible stories. See, for example, Cordelia Drexel Biddle as told to Kyle Crichton, My Philadelphia Father (Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Co., 1955), 21, 24-25, 63, 185-186, 191, 233-236, and Biddle’s article "Why Boxing is Better than the Ball Room" in the Seattle Sunday Times of Apr. 11, 1909, Magazine Section, 4. Of course, Biddle was hardly unique in his love of what he called Athletic Christianity. See, for example, New York World, Jan. 20, 1905, 1; New York World, Feb. 5, 1905, 12; Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Nov. 11, 1909, 9; Japan Times, May 2, 1922, 5; Japan Times, Mar. 27, 1922, 6; and New York World, Aug. 8, 1924, 6S. For elaboration of the originally British doctrine of Muscular Christianity, see Mark Girouard, The Return to Camelot (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1981). For analogous Continental doctrines, see Richard D. Mandell, Sport, A Cultural History (New York: Columbia University Press, 1984). For the attitudes of the early YMCA leaders, see David I. Macleod, Building Character in the American Boy: The Boy Scouts, YMCA, and Their Forerunners, 1870-1920 (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1983). Finally, for an introduction to the role that the YMCA played in East Asia, see Jonathan Kolatch, Sports, Politics and Ideology in China (Middle Village, NY: Jonathan David Publishers, 1972).

EN8. Although the Japanese government was imprisoning socialists as early as 1900, Japanese-language texts extolling the virtues of proletarian sports continued to be published into the 1930s. And, as the Soviet Union did not organize an All-Union amateur boxing championship tournament until 1934, I suspect that most Koreans associated gloved boxing with international capitalism rather than world socialism. For an introduction to the tribulations of socialism in Japan, see Ikuo Abe, Yasuharu Kiyohara, and Ken Nakajima, "Sport and Physical Education under Fascistization in Japan," 2000, InYo: Journal of Alternative Perspectives on the Martial Arts and Sciences, http://ejmas.com/jalt/jaltart_abe_0600.htm. For an introduction to socialist sport, see Robert Edelman, Serious Fun: A History of Spectator Sports in the U.S.S.R. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993); National Folk Sports in the USSR, edited by Yuri Lukashin and translated from the Russian by James Riordan (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1980); and James W. Riordan, "Tsarist Russia and International Sport," Stadion, 14:2 (1988), 222-226. Finally, for a description of the Soviet boxing championships of 1934, see Japan Times, Dec. 12, 1934, 6.

EN9. "Who Is the Grandmaster?" in the Eric Madis collection.

EN10. Heinie Miller, "Now You Tell One!" Ring, Dec. 1922, 5. The occasion was probably the Manila Carnival of 1909. For a photo and a description of a similar match in Tokyo in which the judoka won, see Japan Times, Nov 7, 1913, 1.

EN11. Between the world wars, it was axiomatic in the United States and Britain that boxing was superior to wrestling for personal self-defense. See, for example, J.L. Dorgan, "Wrestling vs. Boxing – Which is the Superior," Ring, Mar. 15, 1922, 5. But, as the Gracies proved during the Ultimate Fighting Championships of the 1980s and 1990s, skilled wrestlers often beat skilled strikers during open competition. As Charles B. Roth wrote in Esquire in June 1949 (page 102): "It all boils down to this: in any kind of a scrap the man with the grab can beat the man with the jab, and -- no matter what the credo of ordinary citizens -- the muscle head [wrestler] always wins!" The standard tactic requires the wrestler to jump in, grasp the boxer by the biceps, and then trip, reap, or cross-buttock him.

EN12. E.J. Harrison, The Fighting Spirit of Japan (Woodstock, NY: Overlook Press, 1982), 46-48; Japan Times, Feb. 9, 1931, 4; Japan Times, Feb. 21, 1931, 4. One difference between "Merikan" and American professional wrestling was that real fights sometimes followed "Merikan" matches. For example, on July 24, 1925, two Hokkaido judo men were stabbed to death after embarrassing some visiting "Merikan" fighters during an advertised free-for-all. (Japan Times, July 25, 1925, 1)

EN13. The Japanese passion for knockouts had various roots. Hollywood films certainly played a role. Jack Dempsey’s knockout of Georges Carpentier (and the fight’s million dollar gate) were big news in Japan in 1921, and from late 1924 until mid-1925 Dempsey’s Fight and Win movies played to enormous audiences in Tokyo. Equally importantly, Imperial Japan had a cult of gaman, or "perseverance." The 47 Ronin who endured all kinds of humiliation before finally avenging the death of their master exemplified gaman, as did boxers who remained standing despite taking a savage beating. Furthermore, in Ian Buruma’s words, in Japan "violence is like sex: not a sin as such, but subject to social restraint." Since boxing was not of Japanese origin, it was not bound by traditional social restraints, and as a result, people who would never have dreamed of saying anything during a judo match felt free to shout "Kill him!" during boxing matches. Finally, there were people who unabashedly enjoyed watching two nearly naked men beating one another bloody. As writer Sadao Togawa put it in Japan Times on May 8, 1933, "I have a friend who is extremely timid but who tells me that after he has seen a boxing match he feels extremely strong." During the 1970s novelist Yukio Mishima also wrote of feeling "purified" after watching exhibitions of stylized violence. For quotes and further analysis, see Japan Times, Jan. 15, 1925, 4; Japan Times, Feb. 21, 1931, 2, Japan Times, May 8, 1933, 8, and Ian Buruma, Behind the Mask (New York: Pantheon Books, 1984), 193.

EN14. On May 8, 1933, Japan Times quoted Shiro Otsuji as saying: "In this country the fighters are handled like a courtesan." For a discussion of how prewar geisha were recruited, see Liza Crihfield Dalby, Geisha (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1983), 222-224. The way in which prostitutes have been recruited in Asia since World War II seems to be similar. See, for example, David E. Kaplan and Alec Dubro, Yakuza: The Explosive Account of Japan’s Criminal Underworld (Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing, 1986), 202-208 and Saundra Pollock Sturdevant and Brenda Stoltzfus, Let the Good Times Roll: Prostitution and the U.S. Military in Asia (New York: New Press, 1992). An alternative is the sumo school model, where the athletes are not indentured servants but instead members of a fictive household. See Yoshihiro Oinuma and Mitsuru Shimpo, "The Social System of the Sumo Training School," International Review of Sport Sociology, 1:18 (1983), 6-19. As for wages, exchange rates varied, but during the 1920s a yen was worth about US $.47, and during October 1925, the average Japanese laborer earned ¥2.15 per day while a Chinese earned ¥1.24 and a Korean earned ¥1.2. Wages dropped, of course, during the Depression. For wages of the 1920s, see Japan Times, Oct. 6, 1925, 4. For Depression-era wages, see Japan Times, June 1, 1931, 1.

EN15. In 1982, the training program of the Korean boxer Duk-Koo Kim included sledgehammering a tire 200 times daily and ingesting vast quantities of garlic and ginseng. Since those aren’t standard American training methods, I assume they are Korean in origin. See Ralph Wiley, Serenity: A Boxing Memoir (New York: Henry Holt, 1989), 116. The various herbal remedies were mentioned in Geoff Crowther and Hyung Pun Choe, Korea: A Travel Survival Kit (Hawthorn, Victoria, Australia: Lonely Planet, 1991), 45.

EN16. For a journalistic introduction to Japanese organized crime, see Kaplan and Dubro, 1986; online, try http://vikingphoenix.com and http://www.newsonjapan.com/html/editorial/0007-Yakuza.shtml. For a similar introduction to the Japanese secret police, see Richard Deacon, Kempei Tai: A History of the Japanese Secret Police (New York: Berkley Books, 1985). The affiliation of the Japanese and American boxing associations was noted in Japan Times, May 23, 1932, 1. The association of gangsters with US boxing is described in Jeffrey T. Sammons, Beyond the Ring: The Role of Boxing in American Society (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois, 1988), 138-183. Front page articles describing a politically motivated assault by a boxer (Susumu Noguchi) on Baron Reijiro Wakatasuki appeared in Japan Times on May 31 and July 1, 1934. An article noting the arrest of former Shanghai boxing champion Paul Lojinkoff on charges of being a Japanese police informer appeared in Japan Times, Nov. 19, 1945, 1. Finally, in "Meeting of Minds: The Grandmasters Speak," Tae Kwon Do Times, Mar. 1992, 34, the Manchurian-born Tang Soo Do teacher Haeng-ung Lee noted that during his youth, Koreans frequently associated martial arts with "gangsters and hoods."

EN17. During the 1990s, US heavyweight boxer Tommy Morrison told journalist Arlene Schulman, "I would fight for an $80,000 or $100,000 purse. My manager would give me 67 percent, and then 40 percent went for taxes. There would be a fight for $100,000, and my end would be about $22,000." And, as another fighter of the 1990s named Tony Tucker reportedly paid 120 percent of his purse to managers and promoters, Morrison’s manager seems to have been comparatively generous. Although the purses of the 1930s were smaller by a factor of 100, managerial greed was not. To give an example, Piston Horiguchi received a guaranteed $1,000 per fight for his five fights in Hawaii in 1936. Fifty percent of the guarantee went to Honolulu fight promoter Steere G. Noda and the rest went to paying Horiguchi’s hotel, training, and travel expenses. (Japan Times, Jan. 9, 1936, 5; Japan Times, June 9, 1936, 5.) See also Japan Times, Jan. 22, 1925, 4, where it is noted that the New York State Athletic Commission allowed main event fighters to receive no more than 50 percent of a fight’s gate, with the rest to be divided among the prelim boys. Morrison’s finances are discussed in Arlene Schulman, The Prizefighters: An Intimate Look at Champions and Contenders (New York: Lyons & Burford, 1994), 59, 70. The Tucker case is cited in Jonathan Rendall, This Bloody Mary is the Last Thing I Own: a journey to the end of boxing (Hopewell, NJ: Ecco Press, 1998), 144-145. Of course, managerial greed was not restricted to North America, and for an example of Japanese promoters cheating the Filipino fighter Don Sacramento, see Japan Times, Feb. 28, 1931, 4.

EN18. Great Northern Daily News, Jan. 6, 1938, 8. It is an adage in Western boxing that a boxer should avoid sexual activity while in training. The theory, which probably has roots in Galenic medical lore, remains popular into the present. See, for example, William Plummer, Buttercups and Strong Boys (New York: Viking, 1989), 91-93. Similar theories also exist in Asia. See, for example, Claude Larre, The Way of Heaven: Neijing suwen chapters 1 and 2 (Cambridge, UK: Monkey Press, 1994), 48.

EN19. See, for example, Andrew Guterman and Robert W. Smith, "Neurological Sequelae of Boxing," Sports Medicine, 4 (1987), 194-208 and Vincent J. Giovinazzo, Lawrence A. Yannuzzi, John A. Sorenson, Daniel J. Delrowe, and Edwin A. Cambell, "The Ocular Complications of Boxing," Opthamology, 94:6 (June 1987), 587-596.

EN20. Although Japan Times did not print sporting

results between December 8, 1941 and August 15, 1945, boxing exhibitions

designed to support the war effort continued throughout the war, and on

March 29, 1944, Dai Ichi Gym’s Kiyoshi Imai died of injuries received while

in the ring. Japan’s first postwar boxing tournament was held at Tokyo’s

Kokugikan Amphitheater on December 29, 1945. Organizers for the latter

event included the Filipino boxer Joe Eagle and the Youth Organization

for the Reconstruction of Korea (Japan Times, Dec. 29, 1945, 2).