By Joseph R. Svinth

Text copyright © EJMAS 2002. Photos copyright © the Paul Lou Collection 2002. All rights reserved.

Acknowledgments: Unless otherwise acknowledged, quotations come from

the Harold Hoshino Scrapbook, Japanese American National Museum archives

number 86.21.1. Funding sources for the research involved in the preparation

of this article included the Japanese American National Museum and King

County Landmarks and Heritage Commission. The assistance of the following

people is also gratefully acknowledged: Terry Abraham, George Hoshino,

Misa Kondo Hoshino, Chuck Johnston, Larry Kobayashi, Paul Lou, Frank Y.

Morimoto, Curtis Narimatsu, Brian Niiya, John Ochs, and Homer Yasui.

Introduction

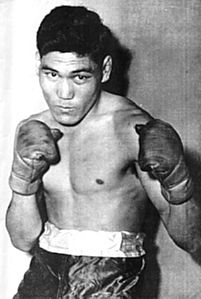

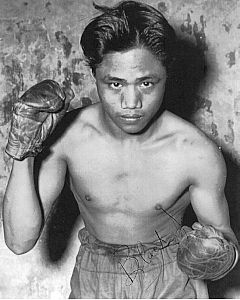

Before World War II, Harold Hoshino was arguably the best known (and certainly best documented) boxer of Japanese descent to fight in the mainland United States. A Seattle Golden Gloves champion in 1937, Hoshino fought professionally 42 times. Of the 41 bouts for which results are known, his record is 36 wins, 3 losses, and 2 draws. Because 29 of these victories were by knockout, Hoshino became known as the Japanese Sandman or Homicide Hal, and a hero to the Nisei of the Pacific Coast.

Harold Hoshino. Courtesy the Paul Lou collection.

Background

Harold Hoshino’s father Katsunosuke Hoshino came to the United States in August 1906. He eventually settled near Pendleton, Oregon, where he became a truck farmer, and by 1913 he was successful enough to send home for his wife Yoshi, who arrived in May 1914. Eldest son Shoji, the future Harold, was born in Pendleton on April 22, 1916.

A former high school math teacher and baseball coach, Katsunosuke Hoshino

insisted his six children (four boys and two girls) excel in whatever they

attempted. As a result son George was valedictorian of his class in 1936,

daughter Helen graduated from the University of Washington, and even the

athletically inclined Harold belonged to the National Honor Society.

Amateur Boxing Career

As a high school senior in 1933, Harold Hoshino stood about 5’4" tall, and weighed about 125 pounds. In high school he played on the varsity football and track teams, so following graduation he naturally took to boxing and wrestling in local smokers. Early boxing opponents included Hank Merriman, Bud Hiatt, Peter Hanley, and Art Chamness.

Because three of Hoshino’s first five boxing matches ended with wins by knockout, a Pendleton sportswriter named Bob Cronin wrote the Seattle boxing trainer Lonnie Austin to tell him that he needed to check this kid out. So, in the fall of 1935, while returning to Seattle from a trip to California, Austin stopped in Pendleton to talk to Hoshino.

While not impressed with Hoshino’s awkward style, Austin saw enough potential to make a second trip to Pendleton in December to watch Hoshino fight a Portland club fighter named Al Mustola. "Mustola hasn’t been knocked down many times during his fighting career," explained a writer for the Pendleton East Oregonian on January 2, 1936, "and perhaps Hoshino hit him just a little bit harder than he’s ever been clipped before. On all three knockdown occasions Mustola was coming in and Hoshino had a square shot at an unprotected jaw. The Japanese lad undoubtedly swung from his toenails on every one of those punches and the fact that Mustola didn’t fold for the 10 count was no fault of Harold’s."

Impressed with Hoshino’s knockout power (something few featherweights have), Austin invited the young man to train with him in Seattle.

Lonnie Austin was born in Wisconsin in 1880 and came to Seattle with his parents in 1887. He started in athletics as a gymnast, and during a meet held as part of the 1905 Lewis and Clark Exposition in Portland, he took second place. About the same time, sportswriter Ed Hughes of the Seattle Times convinced him to take up boxing, a recommendation that panned out, with Austin winning the Northwest amateur welterweight championship in 1906 and 1907. After that he turned pro. He had a total of four professional bouts -- two wins by knockout and two draws.

In 1907 Austin took a job as boxing instructor at the Seattle Athletic Club, but two years later he quit that job to become a trainer and promoter of professional boxers. (Although prizefighting was illegal in Washington State, 4-round exhibitions between members of athletic clubs done for the amusement of other club members were not. Furthermore, the promoters didn’t pay the fighters, but the fighters’ managers, and, as boxing impresario Biddy Bishop told a Seattle judge in January 1930, how managers subsequently distributed the money was none of his business. The reason that such thin fictions worked was that Seattle boxing fans included Seattle Times publisher Alden Blethen and his friends.)

Austin’s first card was held at the Pike Street Theatre in 1909, and his best boxers included Pete Muldoon, Steve Reynolds, and Johnny O’Leary. His best-known boxer, though, was probably Nate Druxman, who later became Seattle’s leading boxing promoter.

In 1911, Austin went into partnership with Dan Salt. The way it worked was that Austin did the training while Salt did the promoting. Dode Bercot was the most famous fighter to develop from this relationship. The Salt-Austin partnership ended with the death of Salt in 1925. George W. ("Biddy") Bishop then took over Mrs. Salt’s interest in the firm.

In January 1931, Washington State enacted legislation that legalized six and eight-round fights. Meanwhile, Austin and Bishop weren’t getting along well, and in part due to their squabbling, Nate Druxman became Seattle’s leading fight promoter. This led to additional problems, and so on January 8, 1933, Austin and Bishop dissolved their partnership. Austin then affiliated with Ed Bremer of Bremerton and Frank Smithers of Yakima, and began staging fights at the Seattle Civic Auditorium on Fridays. The big selling feature of the Austin-Bremer-Smithers fights was that they were cheaper than the fights promoted by Druxman at the Crystal Pool on Tuesdays. However, Seattle wasn’t big enough to support two fight cards a week, and eventually Druxman won the promotional war. Therefore in November 1935, Austin decided to devote his future attention solely to training amateurs. [EN1]

Hoshino was not Austin’s first Japanese amateur boxer. That was probably Fred Hanagato, an Issei judoka whom Austin had taught to box in 1912. But Hoshino was certainly his most successful Japanese amateur boxer. "Harold has taken two lessons," Austin wrote his friend J.W. "Bud" Forrester, Jr., in December 1935.

He is quick to learn and I’m sure that you will note a big change when you see him fight again… However, he should not be over-matched by someone who thinks he is better than he actually is now. If the kid takes a licking at this stage of his training it might have a tendency to make him shy.

He wants me to work with him every day and I’m surely willing to do it. I feel that he will be a great fighter if handled right. In time he will be GOOD!

After three weeks in Seattle, Hoshino returned to Pendleton to help on the farm. "Being the oldest son in a large farm family," his brother George recalled in a letter dated March 18, 1999, "Harold felt a special responsibility for the family and the farm and always considered them his first obligations. He always returned home." But fulfilling his obligations as oldest son didn’t mean he couldn’t dream.

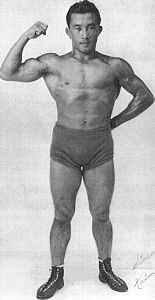

Hoshino’s first thought was that he should become a professional wrestler. Lightweight wrestlers were popular in the Northwest, and Hoshino’s first professional wrestling match took place in Walla Walla, Washington on February 2, 1936. The opponent was Buck Taylor, and the agreement was that Taylor had to pin Hoshino twice in 30 minutes to win. As Taylor proved capable of pinning Hoshino only once, Hoshino was judged the winner. In other wrestling exhibitions staged at Pendleton during 1936, Hoshino also defeated Lonnie Dall, Handsome John, and Young Reed. Then Hoshino met Kaimon Kudo, a Japanese heavyweight wrestler who had grown up in Seattle. "I’ll never forget Kudo," Hoshino told McGuire. "He told me to run at him. I did -- and found myself about 20 feet in the air with aches and pains all over my body. But the fans loved it. That’s when I decided to become a boxer."

Kaimon Kudo. Courtesy the Paul Lou collection.

Hoshino’s return to boxing took place in Hermiston, Oregon, on July 4, 1936. The opponent was Bud Hiatt, and the ring was erected between Safeway and John S. Burnham’s store. The fight was scheduled for six rounds but only lasted five, as Hiatt was unable to answer the bell for the final round.

Upon hearing this news, Austin got hot on Hoshino’s trail. As Malcolm Bauer wrote in Pendleton’s Eastern Oregonian in September 1936, Austin "has been keeping in close touch with Harold, and, in a recent letter sent to his friend, Bud Forrester, he writes:"

During the fall of 1936, Hoshino’s goal was to train for the Seattle Golden Gloves. In preparation, he fought and beat Don Melendy on October 30. Ten days later he lost to Ray Price. On November 18, he fought an exhibition with Jimmy Johnson and on November 23, he lost to Ray Beeson.

During the Golden Gloves tournament, sponsored by the Post-Intelligencer and held in December 1936, Hoshino drew a bye in the first round and the University of Idaho’s Patsy Fitzpatrick in the second. Hoshino and Fitzpatrick entered the ring about 4:00 p.m. on December 8. Said the Post-Intelligencer the following day:

Hoshino decided to take this slow, careful route because he was in no hurry to turn into what he called "a mush-brained punch-drunk ex-pug." The plan worked, too, as on November 15, 1937 Hoshino dropped Al Sloan in the first to advance to the finals. The following night Hoshino fought Ray Smart of Spokane. Hoshino stopped Smart in the second to win the championship, and the day after that, a photo of the knockout was featured in the Post-Intelligencer.

Hoshino’s prizes for this championship included a zippered bathrobe,

a pair of Golden Gloves trunks, a gold-plated medal made in the shape of

two golden gloves, and an all-expense paid trip to the Pacific Coast Golden

Gloves Championship in Los Angeles. Unfortunately Austin didn’t accompany

Hoshino to the Pacific Coast championships. Unescorted, the young man was

quickly distracted by the sights, which included a visit to the Warner

Brothers studio in Hollywood, and as a result Hoshino dropped a decision

to the eventual featherweight champion, Eddie Marcus.

Professional Boxing Career

Upon returning to Seattle, Hoshino turned pro, and his first professional fight took place at the Crystal Pool on December 14, 1937. The opponent was a Filipino veteran named Frankie Villa, and the result was a win by decision for Hoshino. In his second fight, which took place at the Crystal Pool on January 24, 1938, Hoshino won another four-round decision. This time the loser was the Canadian boxer Ernie Schwartz.

On February 1, Hoshino was scheduled for a rematch with Schwartz. The main event featured a Korean boxer named Umio Gen, and as a promotional gag the Seattle Times’ Alex Shults "stunted a picture showing Gen and Hoshino training together."

But no…

‘I’m sorry, sir,’ said Hoshino. ‘I neither speak nor write Japanese.’

Most of the time, however, both Austin and Hoshino kept their ambition in check. As Austin told Budd Fukei of the Great Northern Daily News (January 26, 1938):

He didn’t waste any time getting back into the ring, either. His first fight of the tour was in Seattle on November 15. The opponent was Young Nationalista II. As usual, Hoshino started slowly, but by the fourth he had found his pace, and in the fifth the Filipino put his face in front of a tremendous right that ended the fight.

On December 2, Hoshino was at Al Morse’s Coliseum in Spokane, where he floored Chink Chamberlain in the first. Hoshino returned to Spokane on January 12, 1939. This time his opponent was Al Mustola. Said the papers afterward:

On January 31, Hoshino knocked out Harry Marshall in the first. Two weeks later, he defeated Al Ford in eight. On March 14, in a fight many Pendleton fans listened to on the radio, he stopped Robert "Little Dempsey" Hilado in the fifth. Then, on May 11, Hoshino once again shocked his fans by losing a 10-round decision to the globetrotting Joe Mendiola. Knocked down in the first, Hoshino responded as expected by knocking Mendiola down in the second, but then spent the rest of the fight backing up. As a result the judges gave the fight to the more aggressive Filipino.

On the Fourth of July, Hoshino fought Portland’s Billy Genova at Echo, Oregon. For most Umatilla-area fans, it was their first opportunity to see Hoshino in action and what they saw pleased them: Genova went down twice in the fourth and for the count in the sixth.

Hoshino returned to Seattle on October 16, 1939. Once more, his training included playing football for the Marmots, but he also acted as a sparring partner for the world welterweight boxing champion, Henry Armstrong. Said the North American Times on October 18:

Hoshino, who is popular with the fans because of his aggressive ability, however, waxed a bit too ambitious. After he had nailed Henry with a half a dozen left jabs and a couple of rights, he ran into trouble.

Armstrong got tired of the bombardment and opened up on the fighting Japanese. Hoshino was forced into retreat and took a pasting the last minute of the round which ended the sparring for the day.

Hoshino then left Seattle for Sacramento, where on December 23, he knocked out Rod Bagley in the second. After that, he fought all across Northern California, knocking out Bobby Johnson (three times), Ernie Roybal, and Canada Lee. [EN3]

Although he didn’t make much money (at most he took home a quarter of the gate, and in Sacramento in 1939 a good gate was $992.28), along the way Hoshino became a Japanese American hero. "We all followed Hal Hoshino in those days and pulled for him in every fight," explained Larry Kobayashi, who was then a Los Angeles teenager. "Boxing and wrestling were really popular among poorer minorities." [EN4] This was hardly an idiosyncratic observation, either. For example, in Sacramento on January 26, 1940, there were still people waiting in line after the seats were filled. When matchmaker Fred Pearl announced the sellout, "The crowd outside tried to break in the doors and exchanged punches with the police." The adulation was widespread, too, as in January 1940 a Japanese American group in Chicago named Hoshino its "Nisei of the Week."

Unlike many young men suddenly thrust into the limelight, Hoshino kept his wits about him, and about this time he wrote the following note to "Old Man, Mr. Harold Hoshino":

When I am old and gray, and my aged limbs totter and shake as they carry the burden of old age, I will not envy the youths on their skates, the principals under the bright lights, the sunshine and wide open spaces, and the laughter of children at play. Instead I will play with them -- of course, only mentally. Through these pages I will receive the physical exercise that my tottering limbs cannot supply.

The key to happiness, they say, is to find joy in the things about us. But nevertheless, our minds seem to revert to ‘The Good Old Days’ no matter how happy we may be.

Men never grow old until their thoughts grow old.

Fortunately his hand healed well, and in October 1940 Hoshino resumed his boxing career in Hawaii. When the ship docked in Honolulu on Sunday, November 6, nine European American reporters, four Japanese American reporters, and two former Seattle girls were there to greet him. This time the sights and attention didn’t distract Hoshino, and on November 22, he knocked out Eddie Salazar in the first. "Feinting a left," said sportswriter Kenneth Hamai:

As soon as Eddie got up again, Hoshino stepped back instead of rushing, waiting for his opponent to come to him. This Salazar did, and he was soon a goner. Hoshino hooked in a right to the midsection, knocking Salazar to the mat again, writhing in pain. At this point Eddie’s handlers threw in the towel.

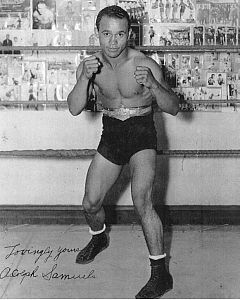

Hoshino’s next fight was with Adolph Samuels. It took place on December 6, and the result was a draw. "Samuels caught the fancy of the crowd as he came off the canvas four times in the second round and gallantly carried the fight to the Japanese boy in the remaining [four] rounds," explained the Honolulu newspapers afterward. "Such was Samuel’s remarkable comeback that the fans were all for him, almost to a man."

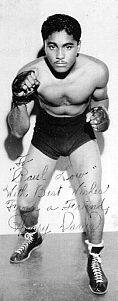

"Lovingly yours, Adolph Samuels." Courtesy the Paul Lou Collection.

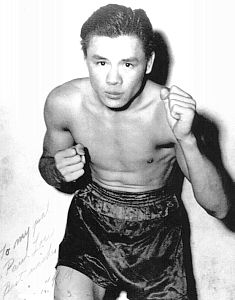

On December 21, Hoshino fought David Kui Kong Young. As Hoshino was a featherweight and Young was a bantamweight, this was technically an exhibition rather than a title fight. Nevertheless Ring Magazine rated Young as the third best bantamweight in the world, and there is no doubt that he was in his prime. Their match took place at Honolulu’s Civic Center, and its gate, about $4,800, was the second highest then on record in Hawaii. To the disgust of the Japanese in the audience, Young had Hoshino backing up for the first seven rounds, and the referee even warned him about stalling. Then, 45 seconds into the eighth, Young made a mistake. As Honolulu Advertiser sports editor Red McQueen put it the following day:

David Kui Kong Young. The inscription reads "To my pal Paul Lou Best wishes K.K. Young." Courtesy the Paul Lou collection.

On February 7, 1941, Hoshino knocked out Cris Crispin in the eighth to win the Hawaiian territorial featherweight championship. Red McQueen wasn’t much impressed by this fight, saying: "Hoshino didn’t beat anybody in Cris Crispin Friday night. I have never seen Crispin show anything that would entitle him to the territorial featherweight championship… Crispin was frightened to death before he entered the ring… And he fell an easy victim. Harold Hoshino, however, did give the best performance of his series of fights here… He showed a nice left hand to go with his devastating right for the first time."

Three weeks later Hoshino scored a technical knockout over the Hawaiian lightweight champion Clever Henry (George Burdett). Although an aging fighter near the end of his career, "Henry didn’t think he’d lose by a knockout," Wallace Hirai wrote in the Hawaii Times.

The Filipino jitterbug outpointed his adversary badly in the first five rounds. In the sixth, however, Hoshino found his range with his looping overhand right. He landed four punches, all squarely on the cheek. It was then that Henry really was beaten. For the first time he realized how much of a socker Hoshino was. He retreated from then on, but the four punches had done the damage.

This victory put the Hawaiian Territorial Boxing Commission into a bind. "As far as the Territorial Boxing Commission is concerned," said boxing commission secretary Tommy Miles, "He [Hoshino] is a double champion. But inasmuch as our commission is affiliated with the National Boxing Association [NBA], Harold is just the lightweight champion. This is according to NBA rules under which a champion cannot hold two titles."

In April 1941, Hoshino returned to Pendleton to help his father on the

farm, but in August he resumed training in Seattle. This time most of his

training took place at Nate Druxman’s gym. Located at 2021 2nd Avenue,

this was the same gym where Harry

"Kid" Matthews, a middleweight from Idaho who would eventually fight

Rocky Marciano for a shot at the

heavyweight title, trained.

On August 26, 1941, Hoshino fought Georgie Hansford. The bout was a double main-event (the other featured Harry "Kid" Matthews), and Hoshino won by technical knockout in the ninth. "Hansford claimed fouls in the third and fourth," said the Post-Intelligencer afterward. "The battle was fierce, with Hoshino receiving part of the punishment in the mouth."

On September 29, Hoshino fought a 20-year old Filipino whose real name was Joe Berje, but who fought as Black Joe, Little Joe, or Little Black Joe. Berje was knocked down three times in the tenth and in the end Hoshino won by technical knockout. It cannot be said to have been an easy win, however, as afterwards Hoshino had to have two front teeth removed.

Five weeks later Hoshino and Berje had a rematch. "It will go down in the record books that Hoshino knocked Little Black Joe out in six rounds," sportswriter Dick Sharp wrote on November 5, "but he didn’t." Explained the Seattle Times’ Vincent O’Keefe:

Joe was already wobbly from hard blows to the head and body when Hoshino caught him with a right flush on the mouth. The Filipino mite wavered like a reed. Referee [Tommy] Clark started counting over him and finished with ‘ten -- and out.’

But Timekeeper [Dean] Effner reached the end of the round and sounded the bell at the count of ‘nine.’ Technically, Little Joe seems to have been counted out after the bell. Actually, he was so far behind Hoshino on points he’d have had a tough time getting anywhere if he had come back -- which he didn’t.

However, Hoshino’s first (and only) fight of the trip took place at the Olympic Auditorium on December 2, 1941. The opponent was a Filipino club fighter named Jimmy Florita, and everyone expected Hoshino to score a victory by knockout. So, said Los Angeles sportswriter Ned Cronin:

As the fighters stepped into the ring I called [Hoshino’s manager Honest Cal] Working over. ‘Tell Hoshino to stay away from this guy for a couple of rounds and then lower the boom on him,’ I cautioned Cal.

‘Never you mind,’ admonished Honest Cal. ‘This kid can knock a horse down. It’ll be a miracle if he doesn’t win.’

That was the night a miracle took place. Florita landed one punch and knocked out three men -- Hoshino, Working, and Cronin.

Ever since then I’ve kept my enthusiasm pretty well in check.

Hoshino routinely visited his friends in the relocation centers, and in early 1943 he donated two pairs of boxing gloves to the recreation center at Hunt, Idaho’s Minidoka Relocation Center. Between farm chores Hoshino also found time to woo and wed Misa Kondo. The Kondo family was from Pasadena, California, and as a result ended up in the Gila River Relocation Center in Arizona. Hoshino met her while visiting Gila, continued writing her after she joined her sister in Michigan in 1943, and married her on February 3, 1944. After the wedding the couple settled in Pendleton, and eventually they had three children. Son Henry, the oldest, served as a helicopter pilot during the Vietnam War and afterward worked for the FBI. Daughter Carol became a schoolteacher while daughter Debbie got a job at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena.

Unfortunately the Hoshino family farm was not so successful. So when offered a lucrative three-fight deal in Hawaii in January 1947, Hoshino accepted. He asked his wife if she wanted to go, and not knowing how tough training and prizefighting were, she and the children went.

Harold Hoshino, 1947. Courtesy the Paul Lou collection.

Hoshino’s first Hawaiian bout took place in Honolulu on April 11, 1947. The opponent was Lefty Quiocho. Before the fight, said the local sportswriter Wilfred Rhinelander, "Hoshino dropped in on us and said he felt as good as ever. Said he knew his wallop was still there, but felt he actually had to get in the ring to make sure." During the fight, said Rhinelander:

In fact, he was making the Pendleton fighter look bad as he counter-punched with sharp precision every time Hal would lead.

Dr. Kimura worked on Quiocho a good 15 minutes before Lefty was able to leave the ring. Even then, supported by a handler on each side, Quiocho appeared plenty wobbly.

Hoshino fought Samuels on May 23, 1947. Although Hoshino won the fight the sportswriters were not impressed. "Little Adolphus is famous for making his opponents look bad," grumbled one of them afterward, "and he did a fair job of making the Pendleton Pulverizer look pretty terrible." The crowd was equally disappointed, as not only had there been no knockout, there had not even been any knockdowns in the fight.

Hoshino’s third opponent was a young African American named Henry Davis. At the time the Advertiser (April 12, 1947) considered Davis, a former AAU champion with twelve professional fights to his credit, "a helluva prospect." And this was a fair assessment, too, as by May 1949 Ring rated Davis third in the world.

Henry Davis. The inscription reads, "To ‘Paul Lou.’ With Best Wishes From a Friend, Henry Davis." Courtesy the Paul Lou collection.

The Hoshino-Davis fight took place in Honolulu on June 15, 1947. Hoshino’s best round was the fifth, as in it he knocked Davis down for a six-count. However, the remainder of the fight was all Davis, with Hoshino going down twice in the sixth round and three times in the seventh, the third time for the count.

Although he left the ring under his own power, Hoshino passed out in

the dressing room afterwards, and as a result he spent the next day in

the hospital under observation. While lying there, he thought about his

goals and objectives. "Some boxers have the reputation of being able to

absorb punches like a sponge absorbs water," Hoshino wrote in a note to

himself. "Now, I wonder if that is a reputation to be proud of and even

less to be gained. Even a sponge has its limits."

After Boxing

With this thought in mind, Hoshino decided to retire from boxing. From 1947 to 1950 he worked as a Coca-Cola salesman in Honolulu. In 1950 he left Hawaii and Coca-Cola for a job selling insurance in Monrovia, California, and continued in that position until his retirement. Unlike Marlon Brando’s character in On the Waterfront, Hoshino was not unhappy about how things worked out, and a clipping he kept in his scrapbook always reminded him why:

Fame is man-given, be thankful;

Conceit is self-given, be careful.

Career Summary

Amateur

| Date | Opponent | Venue | Result |

| 1934 ? | Hank Merriman | Pendleton, OR | KO2 |

| 1934 ? | Bud Hiatt | Hermiston, OR | D4 |

| 1934 Jul 4 | Bud Hiatt | Echo, OR | L4 |

| 1934 Sep 4 | Peter Hanley | Pendleton, OR | KO4 |

| 1934 ? | Art Chamness | Hermiston, OR | KO1 |

| 1935 Mar 4 | George Woodruff | Pendleton, OR | KO4 |

| 1935 Mar 27 | Pinkey Newmeyer | Pendleton, OR | TKO by 3 |

| 1935 Nov 24 | Al Mustola | Pendleton, OR | L4 |

| 1935 Dec 20 | Al Mustola | Pendleton, OR | W6 |

| 1936 Jul 4 | Bud Hiatt | Hermiston, OR | TKO 3 |

| 1936 Aug 23 | Kent Jackson | Long Creek, OR | KO3 |

| 1936 Oct 30 | Don Melendy | Seattle, WA | TKO4 |

| 1936 Nov 9 | Ray Price | Seattle, WA | L3 |

| 1936 Nov 18 | Jimmy Johnson | Seattle, WA | Exhibition |

| 1936 Nov 23 | Roy Beeson | Tacoma, WA | L5 |

| 1936 Dec 8 | Patsy Fitzpatrick | Seattle, WA | L4 |

| 1937 Feb 15 | Frank Burtis | Seattle, WA | W3 |

| 1937 Mar 10 | Jackie Brown | Seattle, WA | KO3 |

| 1937 Mar 15 | Joe Anderson | Seattle, WA | L5 |

| 1937 Apr 30 | Sammy Blackwell | La Grande, OR | W6 |

| 1937 Jul 3 | Tony Lucharo | Fossil, OR | W6 |

| 1937 Aug 19 | Theo Le Gere | Pendleton, OR | KO2 |

| 1937 Aug 21 | Sammy Blackwell | Long Creek, OR | W6 |

| 1937 Nov 15 | Al Sloan | Seattle, WA | KO1 |

| 1937 Nov 16 | Ray Smart | Seattle, WA | KO2 |

| 1937 Nov 29 | Eddie Marcus | Los Angeles | L4 |

Professional

| Date | Opponent | Venue | Result |

| 1937 Dec 14 | Frankie Villa | Seattle, WA | W4 |

| ? | Rolley Thurman | Spokane, WA | Unk |

| 1938 Jan 25 | Ernie Schwartz | Seattle, WA | W4 |

| 1938 Feb 1 | Ernie Schwartz | Seattle, WA | W4 |

| 1938 Feb 15 | Ray Price | Seattle, WA | L4 |

| 1938 Feb 28 | Ray Price | Seattle, WA | W4 |

| 1938 Jun 11 | Harold Hollister | Long Creek, OR | KO3 |

| 1938 Aug 19 | Larry Tipke | Long Creek, OR | KO2 |

| 1938 Oct 20 | Tony Dominguez | Nyassa, OR | KO1 |

| 1938 Nov 10 | Sammy Blackwell | Nyassa, OR | KO4 |

| 1938 Nov 15 | Young Nationalista II | Seattle, WA | TKO5 |

| 1938 Dec 2 | Chink Chamberlain | Spokane, WA | TKO1 |

| 1939 Jan 12 | Al Mustola | Spokane, WA | W6 |

| 1939 Jan 17 | Eddie Ryan | Portland, OR | KO1 |

| 1939 Jan 31 | Harry Marshall | Portland, OR | KO1 |

| 1939 Feb 14 | Al Ford | Portland, OR | W8 |

| 1939 Mar 14 | Little Dempsey (Robert Hilado) | Portland, OR | KO5 |

| 1939 Mar 28 | Jimmy Chapman | Portland, OR | KO3 |

| 1939 May 11 | Joe Mendiola | Portland, OR | L10 |

| 1939 Jul 4 | Billy Genova | Echo, OR | KO6 |

| 1939 Aug 14 | Joe Mendiola | Pendleton, OR | D10 |

| 1939 Oct 27 | Santos Hugo | Seattle, WA | TKO1 |

| 1939 Dec 7 | Rod Bagley | Sacramento, CA | KO2 |

| 1939 Dec 28 | Bobby Johnson | Vallejo, CA | TKO4 |

| 1940 Jan 3 | Bobby Johnson | San Francisco, CA | KO2 |

| 1940 Jan 12 | Bobby Johnson | Sacramento, CA | TKO1 |

| 1940 Jan 19 | Ernie Roybal | Sacramento, CA | TKO3 |

| 1940 Jan 26 | Canada Lee | Sacramento, CA | KO? |

| 1940 Mar 1 | Tomboy Romero | Sacramento, CA | TKO by 7 |

| 1940 Nov 22 | Eddie Salazar | Honolulu, HI | KO1 |

| 1940 Nov 29 | Don Ponce | Honolulu, HI | KO3 |

| 1940 Dec 6 | Adolph Samuels | Honolulu, HI | D6 |

| 1940 Dec 21 | David Kui Kong Young | Honolulu, HI | KO8 |

| 1941 Feb 7 | Cris Crispin | Honolulu, HI | KO8 |

| 1941 Mar 1 | George "Clever Henry" Burdett | Honolulu, HI | KO10 |

| 1941 Aug 26 | Georgie Hansford | Seattle, WA | TKO9 |

| 1941 Sep 29 | Joe "Little Black Joe" Berje | Seattle, WA | TKO10 |

| 1941 Nov 4 | Joe "Little Black Joe" Berje | Seattle, WA | KO6 |

| 1941 Dec 2 | Jimmy Florita | Los Angeles, CA | KO by 1 |

| 1947 Apr 11 | Lefty Quiocho | Honolulu, HI | KO4 |

| 1947 May 23 | Adolph Samuels | Honolulu, HI | W10 |

| 1947 Jun 15 | Henry Davis | Honolulu, HI | KO by 7 |

For Further Reading

Niiya, Brian, ed. More Than A Game: Sport in the Japanese American

community (Los Angeles: Japanese American National Museum, 2000)

Endnotes

EN1. Sources for Austin’s life include Seattle Kind Words Club, Annual Excursion 1929 (Seattle: Pigott-Washington Printing Co., 1929), 27 and the Seattle Post-Intelligencer. See particularly the sports pages for January 6, 1930; January 8, 1930; January 15, 1930; January 8, 1933; July 17, 1931; January 8, 1933; December 24, 1933; January 14, 1934; January 18, 1934; April 16, 1950, and April 17, 1950.

EN2. Both D. Dale Fitzpatrick and John Joseph Fitzpatrick attended the University of Idaho during the mid-1930s, and the university yearbooks do not identify which was the boxer Patsy Fitzpatrick. (Letter from Terry Abraham, Head, Special Collections, University of Idaho, March 1, 1999.)

EN3. On the East Coast, Canada Lee was the professional name of an African American welterweight who subsequently became a stage and movie actor. However, this is several years after that Canada Lee's retirement from the ring. Reader Don Koss therefore suggests that Hoshino's opponent may have been an eponymous Canada Lee that Ray M. Todd, writing in the February 1941 issue of The Ring (pages 46-47), described as Pittsburgh's best featherweight.

EN4. For more on the role that boxing played within

Asian-American communities on the Pacific Coast, plus a description of

the reaction of the Japanese and Filipino communities to Hoshino’s loss

to Jimmy Florita in December 1941, see Cornelio M. Pasquil’s 1994 video

documentary called The Great Pinoy Boxing Era.