Copyright © EJMAS 2003. All rights reserved.

On August 31, 1905, the University of Washington took delivery of the largest wrestling mat on the Pacific Coast. The purchase was due to Dr. Benjamin Franklin Roller, the University’s new professor of physical culture, having convinced the administration that wrestling built character in young men. As Roller told a reporter from the student newspaper (Pacific Wave, October 6, 1905, 1):

The idea that wrestling built character did not originate with Roller. On the contrary, most contemporary physical educators shared the idea. The reason, the US Ambassador to Japan, W. Cameron Forbes, told a Japanese audience (Japan Times, November 27, 1930) was that:

Guts Muths’ ideas gradually spread throughout Germany. In 1811, for example, a Prussian schoolmaster named Friedrich Ludwig Jahn established a Turnverein, or gymnastics club, at Hasenheide, outside Berlin. A strict moralist, Jahn saw Turnen -- the term means more than just gymnastics, and originally included weightlifting and wrestling, too -- as a way of developing character through directed physical activity. In 1833, Adolph Spiess started teaching Guts Muths’ gymnastics in Switzerland. Spiess later developed an entire pedagogical system surrounding these exercises, which he eventually introduced into Darmstadt, Hesse, in 1848. After Germany’s failed 1848 revolution, Turnverein members started emigrating to North America and of course they brought their athletic pedagogy with them.

Nineteenth century Protestant evangelism was another root of the belief that sports built character. Here the Young Men’s Christian Association, or YMCA, played a critical role. The YMCA began in London in 1844 as a social club for shop assistants and other working-class men aspiring to the middle-class. As originally conceived, the YMCA encouraged Bible studies rather than exercise. However, when the organization started opening chapters in the United States and Canada, its leaders found that Bible study classes did not attract nearly as many young men as the gymnasiums of the Swiss and German Turnvereine. Consequently, many YMCA buildings built after 1880 included weight rooms, gymnasiums, and swimming pools.

Although older YMCA leaders were appalled (to their thinking, Christianity was not supposed to be fun), younger leaders replied that theirs was athletic Christianity. "The object of education," said an editorial in a newspaper called Spirit of the Times, "is to make men out of boys. Real live men, not bookworms, not smart fellows, but manly fellows."

While in Britain this philosophy was associated with Charles Kingsley and Thomas Hughes, in the United States its advocates included Catherine Beecher and Dio Lewis. By 1905, the idea was almost universal – even Pragmatist philosopher John Dewey encouraged vigorous athletics -- and increasingly international. The leading Japanese exponent, for example, was judo founder Jigoro Kano.

So, while this explains why the University of Washington administration decided to buy Dr. Roller a wrestling mat, it must be added that the purchase represented one of the few times Roller ever got much support from the University of Washington’s administration. The reason was mostly financial, as both the Washington State legislature and the University administration were notoriously stingy when it came to taking care of their human resources.

Beyond money, however, the administration also objected to a junior professor telling the press what university policy should and should not be. For example, Roller had no use for the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU), partly because the national organization refused to recognize Northwest athletic records and mostly because he disliked its narrow definitions of amateurism. As he wrote in Washington Magazine in June 1906:

In addition, there were conflicting ideas about what an amateur was and should be. For example, sportswriter Caspar Whitney believed that amateurs necessarily came from "the better element," which for Whitney did not include "the great unwashed." Roller, on the other hand, had no trouble rubbing shoulders with working men. Therefore, he preferred the code used by the Washington Interscholastic Athletic Association. Here, the school simply certified that the player had been a student for more than one semester and met academic eligibility, and that was about it. "No attention is paid to the manner in which he [the athlete] ekes out a living," said Roller, "and he is eligible in spite of the fact that in his early childhood he may have run a strenuous pie race to replenish his coffers with a paltry penny."

However, Roller did not control the AAU. Instead, its leaders were men like Whitney. Consequently, when the Multnomah Amateur Athletic Club decided to hold a wrestling tournament in September 1905, the AAU told the Portland club that its wrestlers would have to compete under AAU rules or be barred from future competition. First the leaders of the Multnomah Amateur Athletic Club and then the administrators of the various Northwest universities, colleges, and high schools capitulated to the AAU’s bullying.

Meanwhile, the Washington State legislature began introducing compulsory military drill for incoming college freshmen. While drill had been mandatory at Washington State universities since 1862, it was rarely conducted until Clarence B. Blethen, son of the flag-waving owner of the Seattle Times, restored it to prominence in 1900.

Due to student apathy, drill was effectively discontinued after Blethen graduated in 1903. Outraged, jingoists then convinced the Washington State Legislature to pass a law making drill compulsory for all male university students except aliens (e.g., Japanese and Canadians).

For freshmen, this law went into effect at the beginning of the 1908 academic year, while for sophomores, it took effect at the beginning of the 1909 academic year. Although the newspapers waxed poetic about gray-clad cadets slogging in cadence through the Seattle mud, incoming freshmen were less thrilled. So, after giving the matter some thought, some smart lad spotted a loophole, namely that men trying out for varsity teams might be exempt. Football took care of the fall. Crew, track, and baseball took care of the spring and summer. But what to do during the winter?

Basketball, said some. (Its play dates to 1908 at the University of Washington.) Wrestling, said others. So, when the Multnomah Amateur Athletic Club’s Edgar Frank wrote the University in November 1908 to suggest that the University should join a Northwest wrestling league, the University men were ecstatic. University manager W.R. Rasmussen also supported the idea, telling a reporter from the campus newspaper on November 11, 1908:

Because the alternative was marching through the mud, the prospective wrestlers chipped in for a coach. The man they hired was Frank Vance of the Seattle Athletic Club.

A few words about the Seattle Athletic Club (SAC) are in order. The SAC (which, by the way, is no relation to the present Seattle Athletic Club) was organized in 1897 for the amusement of prominent business and professional men. While the club offered exercise classes, it also provided meals, a bar, and a venue for boxing matches, foot races, and other gambling sports normally banned under city nuisance laws. And, to make sure only the right sort of people applied, the initiation fee was set at $50, with monthly dues of $3.00.

During the 1905-1906 season, Benjamin Franklin Roller was the SAC wrestling instructor. While there, he encouraged University football players such as Polly Grimm to become professional wrestlers. (Back then, pro wrestling paid much better than pro football.)

After Roller left, then Frank Vance became the SAC wrestling coach. While a big talker, Vance was not much of a wrestler, so when he and Portland’s Edgar Frank went to New Jersey for the AAU Nationals in 1909, both were quickly eliminated. He wasn’t much of a coach, either, as when the Washington wrestlers went to Oregon Agricultural College (modern Oregon State) in April 1909, Oregon won 6-0. Rather than accept any responsibility for himself, Vance blamed the loss on biased Oregon officiating.

In January 1910, forty students signed up for wrestling. Vance returned as coach, but only after being promised a salary of $100. (And then grudgingly. While this was as much money as the University of Washington paid a professor each month, Vance said it barely covered his expenses.) Classes took place two afternoons a week, and were arranged so that they did not interfere with Vance’s better paying work at the Seattle Athletic Club.

Following the usual intramural tournaments and smokers, the Washington wrestlers met the wrestlers from Washington State College. The match took place on Saturday, March 19, 1910. Although this was the first intercollegiate wrestling match ever held on the University of Washington campus, the crowd stayed away in droves, preferring instead to go to a school dance. Vance didn’t complain about the officiating this time, perhaps because with Washington officials, Washington won 5-1.

The University’s second meet of 1910 took place in Corvallis on Wednesday, April 6, 1910. Oregon Agricultural College’s Orangemen did almost as well against Washington as they had the year before (the score was 5-1). Oddly, this time Vance made no complaints about the officiating.

Although the season ended at one win and one loss, a victory over Washington State was always reason for Washington to celebrate, and as a result, Washington’s Board of Control decided to make wrestling a minor sport.

What this meant in real terms was that any wrestler who won a match against a wrestler from another school during league competition received a varsity sweater at the end of the season. To eliminate ringers, men (the University did not allow women to compete in "manly" sports in those days) had to have at least 36 accredited hours. Athletes also needed ten passing hours in the previous quarter, and a grade of B or higher in six of those credits.

In 1928, the University of Washington formally adopted AAU rules for wrestling. (Before then, it had used a combination of National Collegiate and AAU rules.) Because AAU rules have changed over time, some words about the rules in effect before World War II are in order. Known as catch-as-catch-can, the style authorized was essentially a combination of various British wrestling methods, to include collar-and-elbow, loosehold, and Lancashire. The competitors wore nothing but shorts, supporters, and shoes. Although holds on any part of the body except the throat and genitals were legal, prohibited techniques included hammerlocks, full Nelsons, toeholds, and hair pulls. To win, a wrestler needed to win two of three six-minute bouts. (The rule that matches could not last longer than fifteen minutes was not implemented until 1913.) A win could be by fall, which required the winner to pin both shoulders to the mat, or by points awarded for takedowns, reversals, escapes, and near-falls.

Weight divisions were borrowed from boxing, where they were useful for handicapping fights for bettors. In those pre-metric days, typical wrestling weights included 115, 125, 135, 145, 158, 175 pounds, and heavyweight. Unlike today, when wrestlers sometimes literally kill themselves trying to make weight, in those days visitors received two pounds of leeway, as everyone knew a wrestler could gain that much weight while traveling.

In late 1913, the AAU introduced a new code of athletic conduct. Much stricter than old codes, it was intended to eliminate the curse of paid athleticism. Essentially, this code told athletes that they must

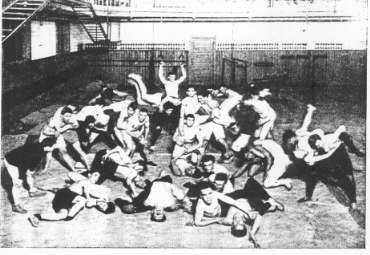

How training was conducted changed every time the University got a new coach. For example, when Frank Vance coached wrestling at Washington, the wrestlers turned out on Mondays from 5:00 to 6:00 p.m. and Thursdays from 4:00 to 6:00 p.m. Under Vance, instruction consisted mostly of the experienced wrestlers practicing their holds on the newcomers. Said the University of Washington Daily in January 1911

Much of this appalling injury rate was owed to inadequate physical preparation. Thus, as late as February 14, 1917, the University of Washington Daily described a track coach’s program of starting training with a series of deep knee bends, flutter kicks, and windmills as "novel…. The exercises make one mighty uncomfortable for several days, the coach declares, but when outdoor work begins there are no more sore muscles and ‘charley horses’ are reduced to a minimum."

Serious injury rates declined during the 1920s and 1930s. The reason was mostly the advent of better-qualified coaches, notably James Arbuthnot and Len Stevens.

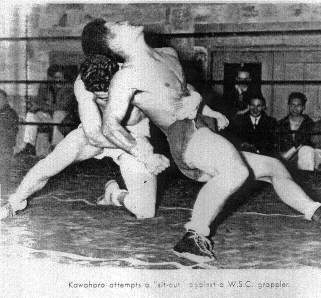

Hippo Kawahara against a Washington State wrestler, 1937. From the

yearbook, Tyee.

During personal communication dated June 20, 1997, former varsity wrestler Irwin Berch described Len Stevens’ program of the mid-1930s.

Intercollegiate matches were generally held in the spring, and during the balance of the year Len fostered intramural competition for conditioning and development. The "Dark Horses" [for which Berch wrestled during intramural competition] was not an actual club, but a small group (including my brother Julian) of mostly Jewish students who met over lunch, who had taken wrestling classes.

Because I was in the 118-pound weight class, and many of the Oriental wrestlers were in the lower weight classes, we regularly competed. Although many of them had martial art training, they were required to comply with AAU and collegiate rules. Still, they were highly regarded as skilled competitors.

I entered UW in 1934, made the freshman team in 1935, and the varsity teams 1936-1938. The major event in the spring of 1936 was the Pacific Northwest regional tryouts for the 1936 Berlin Olympic Games. Mats were set up on the basketball floor, with round robin competition. I entered at the lowest weight (56 kilos), survived all the primary matches, but lost out in the finals, still only 17 years old.