More importantly, however, Japanese Americans were encouraged to wrestle by their community. Japanese parents, for example, liked high school and college wrestling because it was not so unlike judo or sumo that they couldn't understand it. Furthermore, Japanese parents believed that the purpose of an education was not just to teach their children to recite facts, but also to teach them how to interact with others. Thus any education that lacked extracurricular activities was only half an education.

Additionally, both Issei (first generation Japanese Americans) and Nisei (second generation Japanese Americans) believed that athletic success was a way to reduce prejudice and discrimination. Although the Pacific Northwest reportedly has fewer racists than other parts of the United States, its history is hardly a stirring paean to civil rights. For example, the Chinese were chased out of Tacoma during the 1880s, the Anti-Alien League and Ku Klux Klan were powerful during the 1920s, and in 1934 the Seattle Tennis Club publicly refused to admit an African American high school player. Neither Boeing Airplane Company nor the Seattle Public Schools hired many non-whites even as janitors until World War II, and in 1935 faculty at the University of Washington pointedly told an African American woman that they had never graduated a colored person in the past and did not anticipate doing so anytime soon.

Finally, the sight of varsity letters on Japanese American chests brought

credit to the Japanese race. (Back then nations and races were often believed

synonymous.) Thus members of the fraternity called the Japanese Students

Club were particularly pressured to participate in athletics.

During the 1910s, the Japanese American wrestlers were Issei. The first

was 125-pound Kichigoro ("Kay") Yamamoto of Fife, who wrestled for the

Tacoma YMCA in a match against Washington held on Thursday, March 2, 1911.

(Without a travel budget, the Washington team's opponents during

the 1910s were usually regional YMCAs rather than distant state colleges.)

Although Washington's captain Glenn Hoover won the scheduled twenty-minute

match by fall in twelve, observers agreed that it was the best wrestling

of the evening. As the Tacoma Daily News put it: "The Jap is as strong

as an ox and as foxy as a tree of owls. On his feet he had it over Hoover,

but when the two got on the mat the Washington wrestler had the advantage."

Hoover and Yamamoto met again on Saturday, February 24, 1912. Yamamoto had been practicing his groundwork, too, as this time he pinned Hoover in 2:47. Then, to rub salt in the wound, Yamamoto stayed on the mat to wrestle (and win) at 135 pounds, too. And this was just a warm-up, as in May 1912 Yamamoto traveled to Portland, Oregon to win the Northwest AAU wrestling title at 125 pounds. Eighty-five years later, his daughter still had the watch he won as a prize.

Washington's first Japanese American wrestler was an Issei named Fred Yamada. The 105-pound Yamada first turned out in 1913, but lost the varsity berth to Gordon Dickson. The following year Dickson had moved to a higher weight class and as a result Yamada made the first team in both 1914 and 1915.

Yamada had learned to wrestle while serving in the Japanese Navy. So this means he probably knew a little judo. Judo is similar to catch-as-catch-can except for one thing: judo has jackets whereas catch-as-catch-can does not, and the jacket makes all the difference in the world. Despite his small size, he also may have done some sumo, as the Japanese military always liked the sport. Either way, Fred Yamada was a powerful young man and in March 1914 the University of Washington Daily had this to say about him:

Yamada lost to King of O.A.C. [Oregon Agricultural College; the future Oregon State] by a decision, after a full ten-minute round. King was on top 3:43. Yamada put up one of the prettiest exhibitions of bridging seen at the meet, in getting out of the holds of his heavier opponent, who was trained down from 120 to 111 pounds.In the same article, the Daily noted that the Washington captain defeated Oregon Agricultural College's Maki Fuji: "He threw Maki off the mat several times and finally the Oregon man quit after a fall." While the Aggie yearbook did not mention any Japanese on either team, this is not too surprising given the fact that many white people disliked Asians, and as late as 1926 a supposed liberal such as former Washington wrestler Glenn Hoover would write that he was being mild in recommending that Japanese Americans should be repatriated to Japan. Said he: "No permanent settlement of whites should be permitted in the Orient, nor of Orientals in the countries now dominated by whites."

Be that as it may, many diehard Washington fans didn't care if Satan himself wrestled for Washington -- at least as long as he won. So by beating Washington State's Bloomberg in 1915 Yamada earned an honorable mention in the Seattle Times. Yamada's chief notoriety, however, was his belief that wrestlers who lost their matches should cut their hair. This sumo-inspired practice, he told reporters, would ensure that "the evil spell would be broken and victory nestle once more on the defeated banner."

Morimitsu Kitamura was the first Nisei to wrestle for Washington. From Seattle, the 125-pound Kitamura played football for West Seattle and Broadway High Schools from 1914 to 1916. After graduating from high school, Kitamura enrolled at the University of Washington. There he wrestled junior varsity from 1917 to 1919 and varsity in 1920. Technically, he relied more on strength than technique, which meant that 1918 he lost to a former varsity wrestler who was still recovering from a broken wrist. (Masui's 108-pound weight may have been his chief virtue, as he usually won on a bye; as said before, there simply were not that many North American collegiate or YMCA wrestlers who weighed less than 115 pounds.) Therefore Leonard Masui, another Seattle Nisei who was on the Washington varsity from 1918 to 1920, was probably the better technical wrestler.

As the number of second-generation Japanese Americans attending the University of Washington increased during the early 1920s, so did the number of Japanese American wrestlers. In 1924, for instance, a Seattle man named Eitaro ("Kay") Suzuki tried out for the University of Washington team. A judo 3-dan, he expected to do well. Unfortunately, he quickly found that judo and AAU wrestling are two entirely different sports. Not only did he fail to make the Washington varsity, he also failed to make the junior varsity. After transferring to Columbia University's Teachers College in 1929 Suzuki trained with various professional wrestlers including Taro Miyake and Oki Shikina and in 1932 he secured a berth on Japan's Olympic wrestling team. After six minutes and eighteen seconds after starting his first match in Los Angeles, he fell to an arm lock fall applied by C. Karpati of Hungary. [FN1]

Japanese Americans wrestling at the University of Washington during the mid-1920s included Hobei Arai, Roco Okubo, and Tsugo Shinkai. Arai was the probably best wrestler of the three, as he made it into the intramural semifinals. His year ended on Wednesday, January 22, 1925. In the first minute of a match with Loris Gillespie, said the University of Washington Daily:

Arai picked Gillespie up and threw him to the mat rather suddenly, but nothing was thought of it at the time. The two continued to struggle about as before with first one and then the other on top.Arai ended his season with this match.Eventually Gillespie worked into a crotch hold and pinned his opponent for a fall. The minute he was given the decision he asked Referee Jimmy Arbuthnot what was wrong with his shoulder, which hung limply at his side. He refused to believe it was broken, even when Dr. D.C. Hall arrived and took him to the infirmary. Gillespie was going strong for a varsity letter in the 135-pound class.

Gillespie's injury undoubtedly bothered Arai very much, as just two days before the student newspaper had commended him for unusually fine sportsmanship.

Okubo wrestled at 158 pounds in the same 1925 tournament, and advanced to the quarterfinals before being eliminated. The advancement, however, was due more to the weakness of his competition than Okubo's skill. Said the University of Washington Daily on January 16, 1925:

Another interesting bout, from the standpoint of the spectators at any rate, was the match between Byers and Okubo. Neither was in any too good condition and neither cared to use any more exertion than was absolutely necessary. They danced around, facing each other for quite awhile, to the amusement of the onlookers, who urged them to tear into each other.Byers, when he was on top, was quite content to grab his opponent around the waist and wait for the timekeeper to come to his rescue. After some persuasion by Referee Jimmy Arbuthnot he finally got down to wrestling but was thrown in the extra overtime period when his wind gave out.

Nisei wrestlers of the late 1920s included Seattle's Kinji Kanno and Bellevue's Frank Yabuki. Both men wrestled at 125 pounds, and in February 1928 both men advanced to the quarterfinals on byes. Kanno, who held a first-degree black belt ranking in judo, lost in the semi-finals. Yabuki, on the other hand, advanced to the finals before losing.

On May 1, 1929 the University of Washington varsity wrestlers met a Japanese judo team from Tokyo's Waseda University. In this match, said the University of Washington Daily's Jim Hutcheson, Washington "had its athletic conceit knocked into a cocked hat." Which is not surprising, since the Waseda team was a varsity judo squad pitted against what by today's standards was little more than an intramural freestyle wrestling squad.

The Japanese coach was K. Ugiiye and the manager was Ujima. The team captain was Kasahara, 5-dan. Other members included Suwa, 4-dan and Takahata, Endo, Otaki, Yada, and Ozaki, all 3-dan. At Washington the Japanese won two and drew three. In the words of the Daily, at 125 pounds, "Takahata of Waseda choked Cliff Bloom unconscious. Bloom revived, but lost the American style of the bout." At 135 pounds Suwa beat George Douglas in two straight. At 145 Mike Webster earned a draw: he won at catch, lost at judo, and settled for a draw during the third session of catch. At 175 Saigo Ozaki drew with Howard Olson: Olson lost at judo, won at catch, and then failed to successfully strangle Ozaki in the third. Finally, in the heavyweight division, Lester Lev also got a draw. He lost at judo, won at catch, and then settled for a draw in the third session of catch.

Auburn's George Terada was Washington's first Japanese American wrestling star of the 1930s. In February 1934 Terada showed plenty of aggressiveness as he took two falls from Cy Braden, thus winning the intramural 129-pound division. The following November Terada entered the 138-pound division of the intramural tournament and made it to the semi-finals before being eliminated. Impressed, the University's varsity wrestling coach Len Stevens invited Terada to join the team, which he did. The highlight of Terada's 1935 season was when he defeated Joe Riker of Washington State College in February 1935. The low point, though, was his loss to Idaho's Stanley Skiles in May.

Sam Hokari was another popular Nisei wrestler of the mid-1930s. An all-round athlete in high school, Hokari wrestled at 118 pounds from 1935 to 1937. In the spring of 1935 Hokari lost to Idaho's Robert Miller in the finals, but the following year he won his matches against the wrestlers from Washington State College and the University of Idaho.

Hokari's local rivals included a Seattle Nisei named Hiroshi ("Squeaky") Kanazawa. In December 1936 Kanazawa beat Bert Knutson for the University of Washington intramural 119-pound championship, but lost the varsity spot to Irwin Berch. This pattern was repeated in February 1938. Undeterred, Kanazawa persevered and despite his losing the varsity berth once again in December 1938, this time to Harold Maddox, his determination impressed Coach Stevens so much that he asked Kanazawa to turn out for the team anyway. Which Kanazawa did, and in February 1939 he beat a 105-pound Tacoma Nisei named Hideo Hoshide to earn a spot on the varsity squad. Three months later he then justified all those years of trying by winning the Pacific Northwest title at 118 pounds. (During the same meet Hoshide won the Pacific Northwest title at 112 pounds, but as he got it through a bye, the accomplishment wasn't quite as impressive as it sounds.)

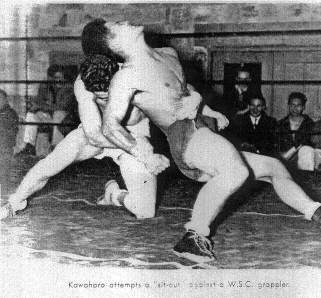

Hitoshi ("Hippo") Kawahara also wrestled for Washington during the mid-1930s. In December 1934 the 129-pound Kawahara advanced to the finals of the annual intramural tournament, then lost to Tom Koeneman of the Dark Horses. This did not reflect badly on Kawahara, however, as Koeneman was a finalist in the 1936 Olympic tryouts. In November 1936 Kawahara was back in the intramural tournament. First he beat the Dark Horses' Irwin Berch, then he went on win the championship and a berth on the 1937 team.

In March 1938 Kawahara had the 128-pound berth to himself. He then proved that he deserved it by taking first place in two separate meets. Following the second victory Coach Stevens acknowledged Kawahara as one of Washington's finest wrestlers and in April 1939 the squad elected Kawahara, a graduating senior, its team captain. Of course, all this acclaim plus a bachelor's degree in fisheries got Kawahara was a job selling tackle at Tokyo Fishing Tackle, but nobody said that success in wrestling helped one get a paying job.

Seattle's Yozo Sato made his Washington wrestling debut during the intramural tournament of 1935, in which he advanced to the semi-finals. In 1936, Sato made the varsity team, where he wrestled at 158 pounds. Sato also wrestled varsity in 1937 and 1938, but due to injuries he did not wrestle varsity after that. In November 1941, however, he did earn second place in Seattle's last important prewar judo tournament.

Of all Washington's pre-World War II Japanese American wrestlers, Takuzo Tsuchiya was probably the most athletically successful. A former judo champion from Auburn, Washington, Tsuchiya won the University of Washington's 1938 intramural championships at 149 pounds despite wrestling eleven pounds over his weight. He then defeated a USS Tennessee wrestler in January 1939 and the Seattle YMCA champion Yeichi Kozu in February, and finished his season by winning his division at the Pacific Northwest championships in March.

The team itself was less successful, however, causing this unkind description in the University's 1939 yearbook: "By way of providing contrast to Washington's many championship teams, Len Stevens' matmen successfully avoided winning a single meet. They were defeated by Washington State 21-3, Oregon State 19-9, Idaho 18-14, and took third place among three teams in the Minor Sports carnival."

During the 1940 season Tsuchiya retained his spot on University of Washington varsity team and once again captured the Northwest championships for his weight. Unfortunately injuries prevented him from repeating the feat in 1941.

Due to the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 there were no Japanese Americans on the University's 1942 team.

FOOTNOTES hit your back button to return to the text.

FN1. The best remembered member of this Japanese Olympic squad was Sumiyuki Kotani, a future judo 10-dan, who placed 5th overall. The team coach was Ray "Pop" Moore.

Photo Credits, Tyee (U.Wash. annual) 1913, 1937.

JCS January 2000