Copyright © Joseph R. Svinth 2002. All rights reserved.

An earlier version of this article appeared in Columbia: The Magazine of Pacific Northwest History, 13:2 (Summer 1999), pages 7-14. Financial supporters for the research involved included the Japanese American National Museum and King County Landmarks and Heritage Commission.

Although Commodore Perry’s men watched a Japanese sumo tournament in 1854, sumo’s first exhibition outside Japan was probably the contest staged for King David Kalakaua of Hawai’i in February 1885. (The barrels of rice wine that the king awarded as prizes also provide the first mention of sake outside Japan.) By June 1896, there was a full-fledged basho, or tournament, held in Honolulu, and shortly after the turn of the century, Japanese immigrants were busily organizing exhibitions and tournaments throughout the Pacific Northwest. For example, there was mention of Issei sourdoughs demonstrating sumo in Alaska during the winter of 1904-1905, and on Tuesday, January 3, 1905, the expatriate Japanese of Vancouver, British Columbia celebrated the fall of Port Arthur with a sumo tournament staged at Vancouver City Hall.

According to the Vancouver Daily Province of January 4, 1905, in sumo:

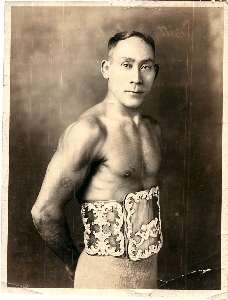

Matty Matsuda, 1920s, at which time he was part of Ed "Strangler"

Lewis’s troupe and billed as the "Lightweight Champion of the World." Courtesy

William Baxter.

There were sumo tournaments in nearby Steveston, British Columbia, too, as during the 1970s, an elderly Japanese Canadian named Hideo Kokubo told interviewer Daphne Marlatt about the sumo ring that had been built in Steveston during his childhood. "A few people who did sumo in Japan and liked it taught it here," said Kokubo, who added that the Steveston tournaments were generally timed to coincide with Japanese New Year’s celebrations.

Sumo began to be mentioned in Seattle newspapers about the same time. For example, a steamship carrying the Japanese national sumo champion Hitachiyama docked in Seattle on Thursday, August 22, 1907. Said an unsympathetic reporter for the Seattle Times afterwards:

Tokugoro Ito, ca. 1910.

Copyright © Dan Deaver 2001. All rights reserved.

The venue for the tournament was the basement of the Adams Hotel, at 513 Maynard Street. The finals started at 9:00 p.m., and were not done until well after the last streetcars had quit running. Besides Inglis and his friends, the audience included several hundred men and perhaps thirty well-dressed women, most of whom were Japanese. The following day, a Post-Intelligencer reporter (probably sports editor Portus Baxter) told his readers:

A gaslight – the one modern intrusion – was swung over the center of the ring. At each end there were posts. On each post hung a rice-straw basket filled with salt and under the baskets were buckets of water with quaint drinking cups. Their use was seen later…

When it was time for hostilities to start, a little dried-up Japanese, dressed in gorgeous kimono and carrying a gorgeous fan, clack-clacked out to the platform and in a high-pitched voice intoned what sounded like a cross between a Methodist prayer and the Merry Widow waltz song. The sing-song gent was the announcer…

Then another official came through with some remarks. He talked in a guttural voice, pulling his words out in dying death-rattles. This was the gioji, or umpire, who corresponds to the American referee. He carries a lacquered baton.

It takes a Japanese wrestler longer to get ready for combat than it did [professional wrestlers Ben] Roller and Bert Warner to get together. [EN2] First each man goes to his own corner. He spits thoughtfully, takes a sip of water, tastes the salt, and then, after a couple of repetitions, goes back to the center of the ring. When the two sumo-tori, as the wrestlers are called, finally face each other, they squat down while the gioji mutters strange words over them. They make a few gestures, rise with humped backs and watch each other like cocks before a fight…

To win a bout, the wrestler must either push his adversary beyond the line of the ring or else throw him so that some part of his body above the knee touches the ground. Seldom do the bouts go more than a minute.

Shouts of encouragement rent the air while the men struggled. At the end of the brief battle each returned to his corner to wait the second bout. Each man’s second gave him a sip of water and a taste of salt. The water is symbolic of the wrestler’s willingness to sacrifice his life in the combat if necessary; the salt is symbolic of fair play; and as the men returned for the second bout salt was tossed upon their brown backs by each second…

Often one of the spectators would toss a hat into the ring at the conclusion of a particularly hard-fought and exciting match. The hat was picked up by a wrestler or his second, and later the owner of the hat redeemed it by paying the wrestler a sum of money approximately what the hat was worth. It’s another way of tossing money into the ring.

From January 14 to 16, 1911, Ito staged another sumo tournament at Seattle’s Nippon Kan theater. Unfortunately the results were not published in either the Times or Post-Intelligencer. Five months later, on May 18, 1911, during the preliminaries to a wrestling match between Ito and a British wrestler named Joe Acton, Ito’s students also gave a sumo demonstration that was well-received by the mostly Japanese crowd.

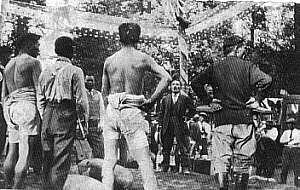

Sumo tournament in Walville,

Washington, ca. 1910. In 1909, the local lumber mill employed 74 Japanese

workmen, and the occasion was probably the Fourth of July or Labor Day.

Note the long johns, probably worn because of the presence of ladies in

the audience. Courtesy the Pacific County Historical Society.

Between 1911 and 1928, English-language documentation of Pacific Northwest sumo is sketchy, and photographs provide most known glimpses of Northwest sumo tournaments of the era. For example, in South Bend, Washington, the Pacific County Historical Society has a photo of a sumo tournament that is dated circa 1910. The participants would have been local logging mill workers. British Columbia’s Cumberland Museum and Archives has photos of some sumo matches held near Cumberland around 1915. The participants in these Canadian matches would have included both loggers and coal miners, and the chief patron was probably the local businessman Eiikichi Kagetsu. From the 1920s, the University of Washington has a photo of a Seattle tournament, and the Oregon Nikkei Legacy Center has a photo of a Portland tournament dated February 13-14, 1926.

Courtesy Oregon Nikkei Legacy Center.

Japanese community newspapers probably provide additional details. Unfortunately, there was not an English-language Japanese community paper in Seattle until 1928. However, on January 11, 1930, this paper, James Sakamoto’s Japanese-American Courier, described Bothell, Washington’s Johnny Funai as the reigning Class B champion, and regretted that Seattle’s Eitaro Suzuki, the reigning Class A champion, had recently moved to New York and as a result was unavailable to defend his crown.

On a smaller scale, there were also many informal sumo contests held during company picnics and family gatherings. For example, the Iseri family of Ontario, Oregon has photographs that show informal wrestling matches staged during White River Valley picnics of the 1920s.

A sumo tournament held during a White River Valley (e.g., Auburn)

picnic of the 1920s. Note star-spangled bunting, suggesting the occasion

is the Fourth of July. The clothed men facing the camera are Sugiyama and

Namba; the clothed man with his back to the camera is Murakami. Courtesy

Mae Iseri Yamada.

Similarly, John E. Davis, who was raised south of Salem, Oregon, during the 1920s, later recalled: [EN3]

The first Puget Sound sumo tournament to be documented by the Japanese-American Courier took place in Seattle on January 25-26, 1930. In preparation, the farmers from White River and Fife trained in their barns while the sawmill workers from National and Selleck trained in their sawdust pits. [EN6] The townsmen from Seattle, however, trained on canvas mats laid out in the basement of the Nippon Kan theater. These mats were open from 7:00 p.m. nightly for several weeks before the competition so that "all those wishing to participate in the coming meet may come there to whip themselves into condition." The tournament itself took place upstairs on the main stage. Unlike judo matches, where the crowds usually sat in relative dignity, the sumo crowd yelled as if watching football or boxing.

During the wrestling, Seattle’s Kaimon Kudo, a judoka and future professional wrestler who stood 5’6" tall and weighed about 160 pounds, lost in the first round to a Portland dentist named Kiyofusa Kayama. In the second, Kayama was himself flattened by Sam Kraetz, the University of Washington’s 207-pound starting center, who had entered the event simply for the novelty.

The Tacoma Buddhist Church’s Seinen Kai, or Youth Organization, hosted a sumo tournament during the weekend of February 8-9, 1930. The communities of Portland, White River, Seattle, Fife, Puyallup, and Tacoma were all represented. Kayama, the Portland dentist, defeated Takido of Seattle to win the grand championship. Seattle’s Henry Yoshitomi won a medal in the junior division. Joe Nishikawa of Puyallup, Frank Takeshita of Kent, and Tom Iseri of White River were also winners, while Johnny Funai, Frank Sugiyama, and Ken Kuniyuki received honorable mention. This is the same Ken Kuniyuki who later became a leader of Southern California judo.

Tacoma youth sumo tournament (Takoma Seinen Sumo Taikai), February

8-9, 1930.

Courtesy the Tamura Family Collection.

The Ohshu Seinen Kan, or Oregon Youth Association, hosted a sumo tournament in Portland during the weekend of January 31 to February 1, 1931. Forty-eight juniors and sixty-six adults entered this tournament. The venue was the Longshoreman’s Hall on Fourth and Everett Streets. The following Monday, Portland’s Oregonian reported:

The only uniform worn by the athletes was a loin cloth. Previous to entering the ring the contestants each tossed a handful of salt into the arena. This is considered a good luck omen. To start the match the contestants squatted in the center of the ring facing each other with both hands on the ground. At a word from the referee they grabbed each other. Each match was for three falls. When any part of a wrestler’s body touched the ground or when he went outside the ring it constituted a fall.

Sumotori from Auburn and Kent, Washington, probably February 1930.

Back row, left to right: Mr. Iseri, Rev. Takemura, Mr. Togawa, unidentified.

Front row, left to right: Sam Katsura, Tom Marutani, Tom Hirai, Tony Tsujikawa,

D. Kajitani, Frank Takeshita, George Hirai, Mike Iseri, unidentified (perhaps

Senda Gawa), Ted Takeshita, Ted Tsukamaki. Courtesy Mae Iseri Yamada.

The Tacoma Buddhist Church hosted another tournament on the weekend of February 25-26, 1933. Teams were expected from Wapato, White River Valley, Puyallup, Seattle, Tacoma, and Portland. The tournament started at 1:00 p.m. Seattle’s Kaimon Kudo and Fife’s Joe Nishikawa (both of whom became American-style professional wrestlers) were the champions. Don Sugai of Salem, Frank Takeshita of Kent, Nobuo Yoshida of Fife, and Juro Yoshioka of Puyallup also did well.

Wapato’s Yakima Valley Sumo Club organized a regional tournament on Sunday, November 12, 1933. The venue was a potato warehouse, and the instructor was Mr. Hayase. One hundred and ninety pound Frank Iseri of Wapato took first place, but Fife’s Nobuo Yoshida and Auburn’s Tom Hirai also did well. "Tom Hirai was my roommate at Selleck Lumber Mill," recalled Toshio Yamanaka during correspondence with the author:

These tournaments celebrated both tradition and community, and were as memorable to the spectators as the participants. Over sixty years later, Tatsuro Yada of Salem, Oregon, told the author:

… On one occasion when I played a match, my partner was a crewman of a cargo boat from Kobe. As I won too often, the rooters for the crew member got angry… So the sponsor asked me to pretend to lose the match this time, which made my patrons angry, and everything fell apart.

The sponsor paid the hotel accommodations, meals and sake for the wrestlers and manager. But many people came to the city from various places to see the match and dropped money at hotels, restaurants and gambling houses, which meant that all in all Japanese Town in Portland prospered.

The Japanese-American Courier hosted its own regional tournament on March 6-7, 1937. The idea was to assist the physical development of Japanese youth through wholesome recreational activities. To keep the second-generation happy, the promoters said they didn’t want stamping of feet, but wrestling. Indeed, said Courier sportswriter Bill Hosokawa, players were expected to:

Twelve-year old Tak "Big Boy" Sagara of Auburn, who weighed 210 pounds, entered the junior competition in this tournament, and evidently he did well, too, as his father later took him to Japan to train. Although a photographer from the Seattle Star also attended the tournament, the Star’s editor decided that the sight of scantily-clad male Japanese anatomy would offend his readers, and he declined to print them.

The Courier held its next tournament on July 4, 1939. As in 1937, Yosajiro Doi was the tournament director. Invitations were sent to players living in Snoqualmie, Eatonville, Selleck, National, Long Beach, Wapato, Bainbridge Island, Bellevue, Fife, Tacoma, and the White River Valley. The match was scheduled to begin at 7:00 p.m., after all the baseball games were done. The scheduled site was a vacant lot near Main and Maynard. Seattle’s first outdoor sumo tournament, it reminded Yoichi Matsuda of being a kid in Japan, where sand-lot sumo:

The final match of the night featured Mitsuru Yano of Seattle and [Tom] Hirai of National, which the former won after a gruelling struggle.

Harry Yanagimachi, while a football player at the University of

Washington, ca. 1940.

Courtesy Yuki Yanagimachi.

The Courier’s third sumo tournament was held during the weekend of March 2-3, 1940. As usual, the venue was the Nippon Kan. Yosajiro Doi was tournament director and Heiji ("Henry") Okuda was tournament chairman. Toshio Yoneyama of Sherwood, Oregon, threw Mitsuru Yano of Seattle to win the grand championship. Meanwhile, Masao Kato of Portland won the round-robin individual title while the college and semi-pro football players Roy Nakagawa of Auburn and George Hirai of National were named runners-up.

Three California professionals named Minoru Chikami, Yoshiya Kinjo, and Takayuki Tashima provided pre-match training. The involvement of Californians in Northwest sumo is hardly surprising, as sumo was very popular in the Golden State. [EN8]

Portland’s final prewar sumo tournament took place on the weekend of February 8-9, 1941. Said the Great Northern Daily News afterward:

Mitsuru Yano, one of the best Queen City [e.g., Seattle] judoists, returned home with the largest gold cup available, a sack of rice, a blanket, and five dollars. Jim Kats Yoshida earned three sacks of rice to carry home, and Joe Nakatsu came home plus two barrels of shoyu [soy sauce]. Peter Fujino, Bengal football star, also reached the locals un-emptihanded.

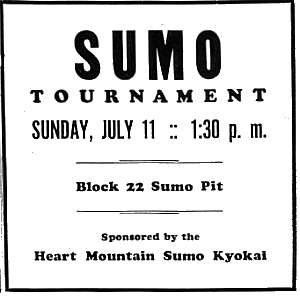

Although the 1942 season was hard hit by the wartime relocation of Pacific Coast Japanese Americans, it was not ruined, as sumo immediately resumed in the camps. For example, there were several tournaments at Puyallup’s euphemistically-named Camp Harmony. Leading players included Harry Yanagimachi, Mitsuro Yano, Mitsuo Mizuki, Tom Hirai, and newcomer Shozo Komorita. There was also a full-scale tournament at Hunt, Idaho’s Minidoka Relocation Center on April 3-4, 1943. The latter tournament started at 1:00 p.m. daily and lasted until it got too dark to see. The ring was built in the warehouse area in Block 22, and as seating capacity was limited, spectators were urged to bring their own chairs. The chairman as usual, was Yosajiro Doi. Winners included Tom Hirai, Harry Yanagimachi, Mitsuo Mizuki, Pete Fujino, Mitsuru Yano, and Shozo Komorita.

Since sumo was very popular in pre-WWII California, during WWII, sumo tournaments were, unsurprisingly, especially popular in relocation centers where there were many Californians. [EN9] Seattle’s Hank Ogawa, for example, learned to do sumo at the Santa Anita Assembly Center in 1942. Ogawa had been a football player and judoka in the Northwest before the war, and after being sent to the assembly center, he started learning sumo from a California champion named Hiroshi "Bud" Mukaye. In the camps, Ogawa preferred sumo to judo because sumo, unlike judo, was a paying proposition. Matches were held every Sunday during the summer and fall, and the fans would put money or ration coupons into a white envelope marked with the names of two players. The winner of the bout would then get the envelope. "I was earning $50 to $75 every Sunday in Santa Anita Camp," Ogawa later told the author. Since laboring for the government only paid $12 to $14 a month, the extra money was important to the Ogawa family, which had three children born in the wartime camps.

A wartime newspaper advertisement for a sumo tournament at Wyoming’s

Heart Mountain Relocation Center. Many Japanese Americans from Eastern

Washington and Oregon ended up at Heart Mountain.

While sumo tournaments did not resume in Washington or Oregon following the war, Fife’s Masato Tamura, by then a well-known judo teacher, won a sumo championship in Chicago in 1954. Since 1977, sumo matches also have been featured in Vancouver, British Columbia’s annual Powell Street Festival, and in June 1998, current Japanese champions held a formal basho (tournament) in Canada.

Dates of Pacific Northwest Sumo Tournaments, 1905-1942

Although a reader of Japanese-language community newspapers could probably double the following listing, the following are the dates of the Pacific Northwest sumo tournaments I’ve found.

Tournament scheduling was not random. Instead, most prewar sumo tournaments

took place near the Lunar New Year’s (e.g., the second new moon after the

winter solstice). The reason was that many Japanese believe that a sacrifice

of prodigious human energy is a good way of ensuring good fortune, and

that a sacrifice near the New Year’s offers the greatest return for the

investment. The apparent anomalies only prove the rule -- the tournament

in Wapato in November 1933 was held to celebrate a good harvest while the

Puyallup tournament of August 1935 was done to celebrate the sponsor’s

remission from disease. As for the July 4, 1939, that was a very auspicious

time for everyone to be wishing for good fortune.

| Year | Lunar New Year | Tournament Date | Location |

| 1905 | February 4 | January 3 | Vancouver, BC |

| 1910 | February 10 | March 3-6 | Seattle |

| 1911 | January 30 | January 14-16 | Seattle |

| 1911 | January 30 | March 1 | Victoria, BC |

| 1913 |

|

October 1 | Lulu Island, BC |

| 1926 | February 13 | February 13-14 | Portland |

| 1929 | February 9 | January 25-26 | Seattle |

| 1930 | January 30 | February 8-9 | Tacoma |

| 1931 | February 17 | Jan. 31 – Feb. 1 | Portland |

| 1932 | February 7 | None found | |

| 1933 | January 26 | February 25-26 | Tacoma |

| 1933 | January 26 | November 12 | Wapato |

| 1934 | February 14 | Unknown | Portland |

| 1935 | February 3 | August 25 | Puyallup |

| 1936 | January 24 | None found | |

| 1937 | February 11 | March 6-7 | Seattle |

| 1938 | January 31 | None found | |

| 1939 | February 19 | July 4 | Seattle |

| 1940 | February 8 | March 2-3 | Seattle |

| 1941 | January 28 | February 8-9 | Portland |

| 1941 | January 28 | March 30 | Seattle |

| 1942 | February 16 | July-August | Camp Harmony (Puyallup) |

Endnotes

EN1. William Inglis, "In the Name of Dai-Jingu," Harper’s Weekly, 51:2629 (May 11, 1907), 678-679.

EN2. See Joseph R. Svinth, "Benjamin Franklin Roller -- A Pioneer of Angles and Feuds," InYo: The Journal of Alternative Perspectives on the Martial Arts and Sciences, 2000, http://ejmas.com/jalt/jaltart_svinth_0700.htm.

EN3. Illustrated Memoirs & History of the Livesley-Roberts Community 1840s to 1940s, compiled by Doug Chambers (Salem, OR: Self-published, 1997), 46-47. I am indebted to Kyle Jansson of the Marion County Historical Society for this citation.

EN4. White River Valley Chapter of the Japanese American Citizens League, A Pictorial Album of the History of the Japanese of the White River Valley (Auburn, WA: White River Japanese American Citizens League, 1986), 10.

EN5. Joseph R. Svinth, "Sizing ‘Em Up: Statistical Relationships between Various Combative Sports in the Japanese American Communities of the Pacific Northwest, circa 1910 to circa 1942," InYo: The Journal of Alternative Perspectives on the Martial Arts and Sciences, 2000, http://ejmas.com/jalt/jaltart_svinth1_0300.htm.

EN6. Selleck is located in eastern King County, about ten miles east of Maple Valley. Built during the early 1900s, during the early 1920s its mill, owned by the Pacific States Lumber Company, employed 600 men and cut 150,000 board feet a day. The mill’s approximately 150 Japanese employees lived in long, shed-like barracks having a central bath house and cook house. Meanwhile, National is in southeastern Pierce County, about six miles east of Elbe. The National mill specialized in cutting the very long spars used to make beams for factory ceilings, and at its peak, it employed about 300 men. The Selleck mill closed in 1937 and the National mill closed in 1944, and today both communities are ghost towns. For additional details, see Kenneth A. Erickson, Lumber Ghosts: A Travel Guide to the Historic Lumber Towns of the Pacific Northwest (Boulder, CO: Pruett Publishing Co., 1994), 17-18, 76-77; Morda C. Slauson, One Hundred Years on the Cedar (Renton, WA: King County Library System, 1967), 48-50; and Ed Suguru, Northwest Nikkei, May 1994, 7, 15.

EN7. Kazuo Ito, Issei: A History of Japanese Immigrants in North America, translated by Shinichiro Nakamura and Jean S. Gerard (Seattle: Japanese Community Service, 1973), 835.

EN8. For an introduction to pre-WWII California sumo, see Eiichiro Azuma, "Social History of Kendo and Sumo in Japanese America," in More Than a Game: Sport in the Japanese American Community, edited by Brian Niiya (Los Angeles: Japanese American National Museum, 2000), 78-91.

EN9. For a Jewish anthropologist’s description of

a sumo tournament held on Sunday, June 10, 1944, see Marvin K. Opler, "A

‘Sumo’ Tournament at Tule Lake Center," American Anthropologist,

47 (January 1945), 134-139. Photographs of this tournament appear on the

National Archives website http://www.nara.gov.nail.html;

for your search, try the keywords "Wrestling" and "Sumo."