Copyright © Jonathan de’ Claire 2002. All rights reserved.

Introduction

Surely not, you say -- isn’t Harada Sensei the principal instructor to the Karate-Do Shotokai (KDS) organisation, and therefore a teacher of the Shotokai tradition? Of course Harada Sensei is Shotokai. However, he is insistent that he teaches orthodox Shotokan karate. A contradiction, you say? Well, not if you delve a little deeper and unravel his long and illustrious trip along "the way of Shoto."

Harada’s kamae

When Mitsusuke Harada, then aged 15, entered the Shotokan dojo in Zoshigaya, Toshima Ward in 1943, Gichin Funakoshi was the undisputed leading light of the Shotokan movement. However, he was not the primary day-to-day instructor. For example, this first class was taught by the formidable 4th dan, Genshin Hironishi, and other notable Shotokan instructors of the day included Wado Uemura and Yoshiaki Hayashi.

Training consisted of practise in kata, kihon, kumite, and ten-no kata. The lessons were for two hours at a time. Because Japan was at war, in the evenings the blackout curtains were always kept drawn and the lights kept low in case of an air attack.

After his first lesson the young Harada was hooked.

More background

The Shotokan was of course the first purpose-built karate dojo in Japan. The money to build it had been raised by Funakoshi’s students, and to manage this venture a group known as the Shotokai ("Shoto’s Association," with Shoto referring to Funakoshi’s pen-name) had been formed.

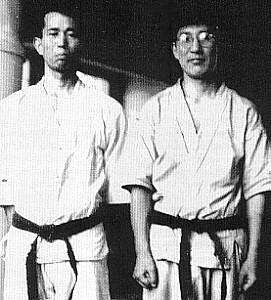

It was whilst training at the Shotokan that Harada first saw the legendary Yoshitaka Funakoshi. The rumour that Waka (Young) Sensei was coming went before him; a buzz of expectancy spread. Yoshitaka was Gichin Funakoshi’s third son, and he had taken over as Chief Instructor the Shotokan and first assistant to his father after the sudden death of Takeshi Shimoda in 1934. Yoshitaka had been awarded the rank of Renshi (an instructor’s grade) from the Butokukai. He lived next door to the dojo with his wife and family. Harada recollected that when Waka Sensei entered the room the atmosphere changed, becoming "charged with energy." He had the reputation of having awesome ability. At this time Yoshitaka Funakoshi was 36 years old and stood 5ft 5ins, he was stockier than his father; had a crew cut, large eyes and a prominent hara. Harada recalled Yoshitaka would select black belts and accept any attack, standing in a deep fudo-dachi posture (his favourite) with an open handed kamae. He also welcomed forceful attacks with bokken (wooden swords) and bo (quarterstaffs). Unfortunately, even though he looked fit and strong he was indeed very ill and in 1945 he died of gangrene of the lungs. This was a truly massive loss, not only to his father, but also a disaster to Shotokan karate; as Yoshitaka was indeed a very special individual who was always researching and developing his father’s karate, he was innovative, dynamic and creative. He searched for and made much progress in the development of Shotokan karate.

Gigo (left) and Gichin Funakoshi

On April 29, 1945, an air raid on Tokyo caused the famous Shotokan dojo to be destroyed by fire. After the demise of the Shotokan, Harada wrote a letter to Gichin Funakoshi asking if it would be possible to continue training. Funakoshi, who was living with his eldest son Yoshihide in Tokyo’s Koishikawa district, replied to Harada welcoming him to train at his son’s house on a private basis.

Upon entering the prestigious Waseda University in 1948 (as his father had done) to study for a Bachelors degree in Commerce, Harada continued his training at the Waseda karate club. Once he had let slip that he had trained at the Shotokan, Harada said that he was "a marked man," as every black belt wanted to test him. Whilst at Waseda he attended training camps and weeklong courses. Initially Toshio Kamata (Watanabe) would teach. In Harada’s year there was also another name that was to become well known – Tsutomu Ohshima. Harada at this time would frequently collect Funakoshi by taxi and escort him to the Waseda dojo, in order for Funakoshi to teach there.

On May 1, 1949, when the Nippon Karate Kyokai, or Japan Karate Association (JKA) was formed, Harada was asked by dojo Captain Joji Takeda to pick up Gichin Funakoshi and take him to the Iomiuri Shimbum Hall. Genshin Hironishi had been instrumental in bringing this meeting together as a way of uniting karateka after the disruption of the Pacific War. It had been Yoshitaka’s last request to Hironishi to try to keep "the way of Shoto" alive, if it was at all possible. At the demonstration that day, it was the first time Harada saw Gichin Funakoshi perform an individual kata – Kanku Dai. Harada subsequently saw Funakoshi demonstrate this form on other occasions and remembers one particularly fine performance at the Japanese Budo Sai. At this time, Funakoshi was trying to reverse the decline in the level of technique and spiritual void that had become dominant as a result of the war. With his son Yoshitaka and main hope for the future of karate now gone, his task had become even more difficult.

Now that Harada had entered University, Funakoshi was more communicative towards him and would often joke, and reflect about Okinawa, his karate teachers and his youth. When asked about the old master’s methods, Harada said Funakoshi’s techniques were "soft, relaxed and unfocussed."

Whilst at Waseda from 1949-1952, Harada trained directly under Funakoshi. Classes were generally on Saturday between noon to 1.30pm. As was his custom, Funakoshi would teach mostly kata, as he believed that kata was the soul of karate. Unfortunately his students wanted kumite and attendance at Funakoshi’s classes was low. Harada later explained, "We didn’t realise the importance of kata then and Funakoshi didn’t explain and that’s where he made the mistake. We, the students, were concerned with the second dimension, he (Funakoshi) spoke in the third. If a senior grade taught kumite whilst O’Sensei was present he would no longer take an interest in the class and look out of the window. This is how we knew O’Sensei disapproved."

Although in his seventies, Funakoshi was "very agile and he had indomitable spirit," and during the first winter’s course of 1949 the frail looking old master engaged Toshio Kamata in kumite. Kamata was very strict with himself and generated great power, and he attacked Funakoshi with an oizuki (a front punch). The old master performed his favourite technique, gedan-barai (a low block), simultaneously grabbing the attacking arm and countering, and Kamata fell to the ground. This caused a great impression all around. Harada’s faith had been restored – Master Funakoshi could still do it and do it well! Those years of kata had done more than allow him to stay active: they even allowed him to continue in kumite despite his advanced age.

At Waseda, Harada also came under the influence of two other extremely outstanding karate masters, both of whom deeply affected his life. These were Shigeru Egami and Tadao Okuyama.

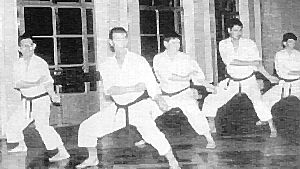

Shigeru Egami and Mitsusuke Harada, 1954

In middle school, Egami trained in judo and kendo, as was customary in those days. He had attended Waseda University to read for a Bachelors degree in Commerce, same as Harada, and while there he had also studied some aikido (though it was not yet called that). In 1931, Egami helped form the Waseda University karate club. His principal teachers were Gichin Funakoshi and Funakoshi’s assistant, Takeshi Shimoda, but he also engaged in a great deal of "special practise" with Yoshitaka, his senior, whom he described as being of excellent character and highly skilled. Egami was an outstanding karateka, generally being regarded as having the finest punch in the Shotokan style – he was an oizuke specialist. During World War II, he was also a teacher at the Nakano School, which was a training school for Japanese commandos and spies. [EN1]

After a chance meeting at the Waseda dojo where Harada was practising individually (as he often did), Egami commended his efforts to improve himself, and offered to help him. So during the next 18 months, the two men generally trained seven days a week, and it marked the start of a friendship that would last many years.

The timing was fortuitous, as this was a time of great innovation and research for Egami. He was developing his already formidable punch into a more relaxed, fluid and more penetrative technique. [EN2] So together the pair researched, spending three hours each day practising, and many more talking about karate, especially theory. Harada improved dramatically as a result of his private tuition.

Egami’s goal at this time was to modify the stiff rigid training that he had undergone for the past 25 years. He realised that this type of technique was seriously flawed. His new technique was a radical concept for Shotokan karate, as it was his theory that the relaxation of the joints and loss of undue tension allowed for the release of true power and penetration. He had a point, too, as even through four cushions that they used as focus pads, Harada could still feel the sickening power. Egami’s blocks were equally devastating: each time Harada attacked his blows would be parried and he would be knocked to the floor.

The result of this research was a softer, faster and more fluid karate, which made Egami’s techniques more powerful than the typical Shotokan karate technique of the day. Since Egami worked closely with Gichin Funakoshi until the old master died, he always considered that the development and direction of his research was in line with his teacher’s wishes. However, tragedy struck as Egami fell ill before he could physically pass on his new found body condition to his students. Fortunately, Harada had already experienced it, and so it turned out that Egami had indeed passed it onto his pupil.

At the first Waseda summer camp that Harada attended (this was probably 1949), he was introduced to an outstanding 3rd dan named Tadao Okuyama. Harada trained under him every afternoon for two years. However, after an angry disagreement with Kamata over technique, Okuyama suddenly disappeared from the summer camp. He left and went into the Tsukuba Mountains 50 miles northeast of Tokyo in search for the truth. A couple of years later he re-appeared in Tokyo to resume private training with Egami. One day Egami told Harada of this, and he used the prospect of a meeting with Okuyama as motivation whilst he practised. In 1955, when Harada was due to leave Waseda, the day of the meeting came. As soon as Harada saw the kimono-clad Okuyama with his long flowing hair, he recalled, "I knew I couldn’t win the encounter. There was something special about him." Harada faced him all the same, but as soon as it had begun it was over. "It was truly incredible," Harada recalled. "So fast!" Okuyama had attacked Harada’s head with an open palm. Okuyama had not even physically touched Harada "but I felt the power, such power, I had never felt that before anywhere." The memory still haunts Harada to this day. Okuyama had not been locked in the past as many of his contemporaries were; he was concerned with the future…how to improve, how to evolve! A long-time partner of the gifted Renshi Yoshitaka, Egami later admitted to Harada that Okuyama’s level was even higher than that of Yoshitaka; so high, in fact, that no one could follow him.

After completing his Bachelor of Commerce degree in 1953, Harada then undertook a Masters degree, which he successfully completed in 1955. Whilst at graduate school, he assisted Hiroshi Noguchi at Waseda and also helped Masatoshi Nakayama teach karate to American servicemen. It was during this time at Waseda that Harada first witnessed the founder of aikido, Morihei Ueshiba, whom Harada later described as "tremendous." Harada was also fortunate enough to see Ueshiba’s final demonstration at the Kodokan in 1969, only months before he died. Harada once spoke of Ueshiba’s apparent ability to throw opponents without touching them to his teacher, Shigeru Egami. Egami told Harada about his own encounter with Ueshiba many years before as a student, likewise finding himself flying through the air without any noticeable physical contact. He then told his student something that would affect his life for the next 40 years: he said, "You must endeavour to produce this effect with karate technique."

In 1955, Harada took a position with the Japanese-owned Bank of South America in São Paulo, Brazil. He was to set sail on the Africa Maru. Egami (whom he had trained with the night before), Motohiro Yanisagawa (a student of Egami from Chuo University) and Yanisagawa’s son Daisuke saw Harada off. (His parents and sister had said their farewells earlier, as requested by their departing son.) During the journey, the ship docked in Los Angeles, and Harada had an opportunity to visit his old friend from Waseda, Tsutomu Ohshima, who was now based in California.

Upon arrival in Brazil, Harada settled into his new job at the bank. The manager, on learning of his newest employee’s karate expertise, asked Harada to do a demonstration for the bank staff. After the demonstration, a young employee approached him and asked to be taken on as a student; but there was nowhere to train! The prospective student was determined, however, and so found a judo dojo that they could use, and the pair began training in October 1955. Soon the student’s nephew joined and then some of his friends came, and in no time the club expanded to some 30-40 students. This was arguably the first public karate school in the whole of South America. Thus Harada, as his instructor Gichin Funakoshi had been before him, was a pioneer of karate. [EN3]

Harada wanted to affiliate his Brazilian club with Japan, and so he wrote to Gichin Funakoshi. When the latter responded, Harada was shocked by the contents of the letter: Funakoshi firmly stated that Harada should start up a separate Brazilian organisation. The reason was that he thought that the art that he had introduced to mainland Japan had been largely spoiled and corrupted. So, by starting a new organisation, he thought that there was a chance for karate to start afresh, away from the squabbling and bureaucracy that had become so commonplace in Japan. Hence the Karate-do Shotokan Brasileo was born.

At the same time, Funakoshi endorsed his faith in Harada, awarding him his godan, or 5th dan, at the very young age of 28. Harada has never sought any subsequent grade beyond 5th dan, feeling it meaningless. After all, how could he grade above his own teacher, who was himself ranked just 5th dan? As a result, this level remains the highest grade attainable in Harada’s subsequent karate organisation the KDS.

In April 1957, Harada received a telegram from Egami informing him of that Funakoshi Sensei had passed away quietly in hospital on the 26th of that month. He had been at his old teacher’s bedside when he took his last breath. Egami had taken on the role of looking after the Old Master and he had learnt much from him, but when Egami fell ill, no one could fulfil his duties. Problems then arose. Specifically, Funakoshi’s family objected to a particularly well-known association (and one bureaucrat of that organisation in particular) arranging the funeral. Therefore a group was formed to attend to the funeral, with Yoshihide, O’Sensei’s oldest son, as Chairman. This group was known as the Shotokai. At this time the Shotokai had no karate significance, but of course many of its members did, among them Hironishi, Egami, and Yanisagawa. Anyway, members of the Shotokai were executors to the estate and trusted by the Funakoshi family. Under the direction of Dr. Nobumoto Ohama, the President of Waseda University, the Waseda Shotokan club joined the Shotokai, too. After the funeral, the Shotokai was not dissolved and the universities of Chuo, Senshu, Toho, Gakushuin and Tokyo Noko joined. At this point, however, there were no technical differences in their karate: all were practising Shotokan.

Egami described all of this in letters to Harada. Harada with his close ties to Funakoshi and Egami, subsequently became a member of the Shotokai. Meanwhile, Funakoshi’s students began squabbling about the direction the founder’s style should take. The Shotokai were dedicated to preserving the orthodox teachings of Gichin Funakoshi, and Egami believed that future development should lead along the path the old master had intended. Certainly it could be said that Funakoshi did not approve of the direction certain senior karateka were taking his Shotokan karate.

During his stay in São Paulo, Harada also discovered the Brazilian fighting art of capoeira. One day, a supposed friend brought a senior practitioner to Harada’s dojo. Unbeknown to Harada, this was to be a challenge. Luckily, one of Harada’s students had overheard the two men’s intentions, and informed Harada of them. Harada, now aware of the situation, stepped up the intensity of the practice, which was being watched by his potential challenger. Then, at the end of the lesson applied a little more psychology, approaching the capoeirista saying he would accept a challenge at anytime when offered. But the professor of capoeira declined and never returned.

On another occasion, however, a challenge was offered. This was at the University of Rio de Janeiro, and this time it was accepted. Harada later explained that his opponent used the tempo of the music to breathe, so Harada advanced each time he inhaled, eventually driving the capoerista into a corner. Then he showed a technique that clearly would have ended matters, but did not go through with it so that the man did not lose face. Nevertheless, these encounters with that energetic and acrobatic Brazilian art, with its wide-ranging sweeping and spinning leg movements, led Harada to revise his own practice. For one thing, he thought it necessary to become far more mobile and adaptable than he had previously deemed acceptable. Harada Sensei was beginning to develop his own "way," shaped by his experiences.

Whilst working for the bank, Harada Sensei was asked to act as a bodyguard to Japanese Royal Family -- Prince Mikasa and his wife Princess Yuriko – during their visit to Brazil in June 1958. In case of any attempts at their safety, it was decided to appoint Japanese bodyguards in order to avoid any diplomatic incidents. Amongst the all -Japanese bodyguards, were also three senior judoka – Mr. Kihara, 7th dan, Mr. Katayama, 6th dan, Mr. Fukaya, 4th dan, and of course Harada Sensei. The work lasted approximately two weeks, the duration of the state visit.

Harada as bodyguard to Prince Mikasa and Princess Yuriko, June 1958

Late in 1959, Tsutomo Ohshima, now also a 5th dan, came to Brazil to visit his old friend Harada for a couple weeks, and while there, he taught at his dojo. Whilst he was there the two met up with Masahiko Kimura, a famous judoka from Takushoku University who was then touring South America as a professional wrestler.

By 1963, Harada had some 16-17 black belts under him, all 1st dans. His first black belt was Mr. Yasuda, a fellow bank employee. By now, other instructors had come to Brazil and the usual petty rivalries had begun, and so Harada decided it was time to move on.

Late that same year, Harada was invited to Paris. Karate students there had heard of him and raised sufficient funds to buy an air ticket in order that he could visit them. Harada resigned his position at the bank, with the intention of taking a year out to travel, before returning.

On his arrival in Paris, Harada taught at the dojo of Tetsuji Murakami, a Yoseikan 3rd dan who had come to France at the invitation of Henri Plee. At this time, Harada was teaching orthodox Shotokan karate. Practise mainly consisted of ten-no kata, kihon (basics), and sambon kumite (prearranged sparring).

Whilst researches with Egami had certainly become a part of Harada’s practise, these benefits were being expressed through a university style he had been taught. However, Harada was aware of the rigidity of the Shotokan he had been practising and endeavoured to evolve and progress. And, unlike many of his contemporaries, Harada Sensei always took part in each lesson. That is, instead of standing in the back of the room watching, he would accept each student in turn, thus allowing a strong bond to be built. Another instructor involved with Harada at this time was a Vietnamese named Hoang Nam. But, again, jealousy and politics appeared, and again Harada decided to take his talents elsewhere.

This time it was to Britain, where he had been invited by the famous judoka, Kenshiro Abbe. Abbe was a budoka of high recommendation: not only was he an 8th dan in judo, but he also held a 6th dan in aikido (he studied directly under Morihei Ueshiba) and dan ranks in kyudo (archery), juken-jutsu (rifle-bayonet fighting), and kendo.

Harada’s first public demonstration in Britain was on November 23, 1963. The occasion was the National Judo Championships being held at the Albert Hall in London. A number of martial arts demonstrations were performed aside from the Judo competition, to include kendo (Tomio Otani), aikido (Masashiro Nakazono and Masamichi Noro), and karate (Harada and an assistant). Harada also published an article in Judo News entitled "The Essence of Karate" that provided insight into Harada’s thinking at the time. When considering the dynamics of karate training, Harada thought speed, endurance, and strength were the three chief factors involved. Elements of these that he considered important were correct form of posture, relaxation, concentration, and natural movement. He also commented on karate in Europe, writing that he thought that European karateka could become as proficient as Japanese, once the fundamentals were understood.

After this exposure, and after giving a seminar in karate at the Abbe School of Judo on November 7 and 8, 1963, Harada was asked to give a number of seminars and demonstrations around the U.K. So from early in 1964 until 1968, Harada alternated teaching between the U.K. and Brussels. His organisation was fast growing into a large Anglo-European group.

It was during one of these trips to Brussels, that Harada Sensei met Jotaro Takagi. Takagi, the future chief instructor of the Shotokai in Japan, was a graduate of Chuo University, and he was in Europe on a business trip. Takagi showed Harada new practise developments from Tokyo and so, for six months, towards the end of 1967, Harada returned to Japan to investigate.

Harada Sensei learnt many things on this return to Tokyo, but on the whole felt that it was not a good trip. Harada was unsure of the direction that Shotokai was taking. Indeed, to be blunt, he had grave reservations. He visited his old friend and teacher Shigeru Egami to inquire as to his position – Shotokai or Shinwa Taido. But Egami sat on the fence, not giving an answer one way or the other. This depressed Harada greatly. However, one thing was confirmed; a replacement had been found to take Harada’s place in Brazil – Arinobu Ishibata, a graduate of Chuo University, was to be sent to South America. Thus Harada was now free to stay in Britain.

A summer school at Grange Farm, ca. 1967-1968

Early summer schools were held in the Spartan conditions of Grange Farm. At this time Harada’s karate group was a part of the International Budo Council (IBC), but when Abbe left to return to Japan in 1966, Harada resigned from the IBC, as he was unhappy with its politics. It was then that he decided to form his own Karate-Do Shotokai (KDS) organisation. Initially, there were ten clubs up and down Great Britain; he himself did most of his training and teaching at Kenneth Williams’ dojo in Hillingdon. During this time, Harada earned a reputation as being an uncompromising instructor, always willing to demonstrate his ideas, at great risk to himself, in the name of progress.

Upon Harada’s return from Japan, many of Harada’s senior students travelled to Japan to experience the new ideas for themselves. But, in 1971 Harada took a definite direction, returning to the more orthodox style he had experienced in his University days, and especially the invaluable year and half under the tutelage of Shigeru Egami. Whilst this was welcomed by many, others wanted to carry on with the way they had been practising. This led to another inevitable split in the organisation. But Harada Sensei was now untethered by the constraints of Japan. Having spent 3-4 years with unsuccessful experimentation, he had drawn the line, effectively breaking technical ties with Japan.

As Harada examined his own background and karate-do itself, slowly but surely changes began to appear in his practise. For example, counting aloud stopped, for this was verbal stimulation, conditioning the student to respond to sound rather than the visuals. Therefore he started using visual perception as the trigger. Similarly, Harada’s practise began to evolve into a relaxed and flowing style with dynamic penetrative power. And along the way, the KDS organisation grew, to a point where there were sometimes three separate courses being held on any one weekend, in different parts of the country.

Due to politics, the KDS suffered another major split in 1988. At this juncture, the organisation halved its numbers, and many senior grades were lost after investing years of intensive training and time on them. Bitterly disappointed, Harada considered returning to Japan. But instead he decided to persevere with his faithful group of KDS students and again invest his time and energy into his karate. The faithful remnants of the KDS would now develop into an organisation free of politics and power chasers. Moreover, those that remained in the KDS were there for the good of karate; they were there to train and improve, with no hidden agendas. So, spurred on by the enthusiasm of his group, Harada continued taking new and innovative approaches to training, thereby pushing the study to new levels.

Harada is a great exponent of the bo

In today’s KDS organisation, Harada teaches body language and perception through the variety of exercises that his research has produced. For example, there are constant practices of movement, exercises designed to teach practitioners to know and keep the correct distance, and generally fine-tuning the students’ bodily reactions in regard to an opponents’ movements. Whilst correct structure and form within movement is adhered to, relaxation is viewed as paramount to facilitating a mobile body. From this natural and relaxed state, Harada can produce dynamic speed and power; even now, in his early seventies, he seems still to be pushing back his own boundaries with each practise. He is a true testament to his own research and life’s work. "Age and size should be no barrier in karate," he says, and this is something that many younger and larger opponents will testify to, as being very true, where Harada Sensei is concerned!

In October 1998, after many years of resistance, Harada received an invitation from Nihon Karate-do Shotokai to demonstrate at the main dojo in Japan. The celebration, which commemorated 60 years since conception of the Shotokan and the 130th anniversary of Gichin Funakoshi’s birth, included an international meeting in Tokyo. Harada took a select group of his KDS students with him, and in his words, they made "a huge impact" at the display attended by all of the Japanese groups plus visitors from Europe and South America. Thus, Harada Sensei had come full circle. After beginning his karate training at the Shotokan back in 1943 and being outside in the cold for many years, he was now back with his own group the KDS, wholly being accepted by the Japanese, and himself recognised as a true Master of Karate by his mentors and peers.

Endnotes

EN1. For more on the Nakano School, see Louis Allen, "The Nakano School," Japan Society Proceedings, 10, 1985, 9-15 and Graham Noble, "Master Funakoshi’s Karate," reprinted in Patrick McCarthy, Karate-do Tanpenshu (Brisbane, Australia: International Ryukyu Karate Research Society, 2001), 111-117.

EN2. Egami’s writings include The Heart of Karate-Do (Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1980). An extract appears online at http://www.shotokai.cl/gallery/beyondpreface.html.

EN3. For more on the development of karate in Brazil,

see Ubaldo Alcantara and Antonio Rodrigues, "Karate in Brazil: An Overview,"

Journal of Combative Sport, December 2000, http://ejmas.com/jcs/jcsart_alcantara1_1200.htm.