Copyright © EJMAS 2000. All rights reserved.

INTRODUCTION

In 1890, the Brazilian government enacted a law that prohibited the immigration of African and Asian peoples. In 1907 the United States enacted laws restricting Japanese immigration, so, wanting agricultural labor, in 1909 Brazil amended its definition of "Asian" to exclude Japanese. As a result, about 200,000 Japanese emigrated to Brazil before 1941.

Brazil

Many of these immigrants were Okinawan, so surely there were some who practiced karate. But, unlike judo, sumo, and kendo, karate was a little-known art until the 1920s, even in Japan. Furthermore, there weren't karate competitions outside university clubs until the 1950s. As a result, there aren't many clues about its practice in the old days.

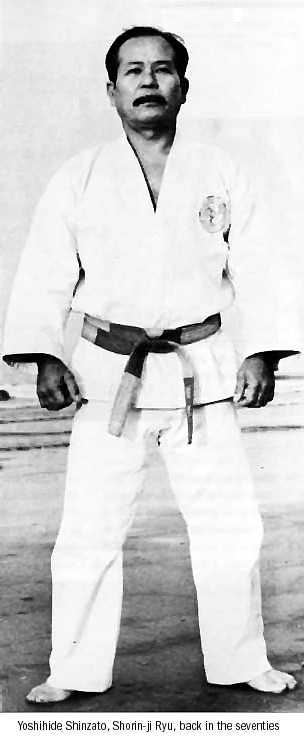

The first person believed to have taught karate in Brazil is Yoshihide Shinzato. Shinzato was born on Okinawa on March 15, 1927 and at the age of 12 he began studying karate with Choshin Chibana. Chibana was a direct student of Anko Itosu, and during the 1920s he started calling his style of karate "Shorin-ryu". His kanji meant "Small Wood" rather than "Pine Forest," so did not necessarily refer to the Shaolin Temple in China, and as a result the system is sometimes known as Kobayashi Shorin-ryu.

Anyway, Chibana had a dojo in the courtyard of Baron Naijin's estate in Shuri, and he taught there until the US invasion of Okinawa in 1945. Following the battle for Okinawa, he relocated first to the Chinen Peninsula and then to Naha. Probably Shinzato trained with him during most of this time.

In January 1954 Shinzato came to Brazil as part of a group participating in a celebration of the 400th anniversary of the founding of the city of São Paulo, and after the show he decided to stay. According to the official story, in September 1954 he began training one day a week with some youths from the Japanese colony at his rented house in the city of Santos. However, he did not officially open a dojo until 1962, and by then others were already teaching in Brazil, including some fairly high-graded people.

Another early karateka was Koji Takamatsu of Wado Ryu. According to some sources, he came to Brazil in 1955; according to others, it was early 1956. Anyway, his students have claimed he began immediately to teach karate. However, no accurate documentation has been found and so the matter remains subject to dispute.

Therefore Mitsuke Harada is the first Brazilian karate pioneer whose rank and influence are both documented and undisputed. Born in Manchuria in 1928, Harada was the son of a Japanese army officer. When he was nine his father was transferred to Tokyo, and of course his family followed. In 1943, when he was fifteen, Harada met Yoshitaka "Gigo" Funakoshi, who was the son of Gichin Funakoshi, and as a result started to train at Funakoshi's Shotokan Dojo. His first instructor was Motonobu Hironishi.

In 1945 Gigo Funakoshi died of a lung disease and so Harada began training under other Shotokan seniors. Once a week, at Hironishi's request, he received instruction in kata from Gichin Funakoshi. His friends included Tsutomu Ohshima, who later pioneered Shotokan karate in California. Ohshima has written that many of the young men in those days didn't like practicing their kata, but their seniors made learning it a requirement.

In 1947, the US Air Force started a survival school for aircrew, and by 1949 judo and other Japanese martial arts were part of the curriculum. The Japan Karate Association (JKA) contributed instructors, to include Isao Obata and Hidetaka Nishiyama, to these US programs. During this period, Harada was personal assistant to JKA leader Masatoshi Nakayama, and as a result he got experience instructing US military personnel in Japan.

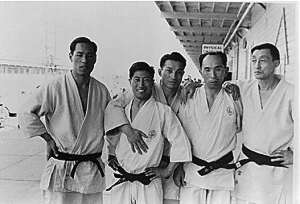

US Air Force martial art instructors, 1953. Left to right: K. Hosokawa (Taiho jutsu), Toshio Kamata (JKA), Tsuyoshi Sato (Kodokan judo), Isao Obata (JKA), Kenji Tomiki (aikido). Photo courtesy Keigi Horiuchi.

In 1948 Harada became a member of the Waseda University karate club, where the chief instructor was Toshio Kamata. In 1953 he entered graduate school at Waseda and meanwhile he studied karate directly under Shigeru Egami.

After getting his master's degree in 1955 Harada went to work for a Japanese bank, which immediately sent him to work at its Brazilian subsidiary, the Banco América do Sul. At the time he was ranked 3-dan, which was very high for those days. (The highest Shotokan grading of the mid-1950s was 5-dan.)

Upon arrival in São Paulo Harada started teaching karate at a judo club run by a famous teacher named Hikari Kurashi. In 1957 Harada gave karate demonstrations in Rio de Janeiro and in 1959 he received his friend Tsutomu Ohshima for a seminar that lasted two weeks. And, due to the high quality of this instruction, Shotokan soon became famous in Brazil. As a result Harada was promoted to 5-dan.

Harada left Brazil in 1963. He went first to France, but due to visa problems he ended up in Britain. In 1967 he established the Karate-Do Shotokai in Cardiff, Wales, and he remains there to this day.

Unfortunately Harada's senior Brazilian student, Tomeji Ito, was not able to hold Harada's organization together and Brazilian karate soon splintered. Part of the problem was, unsurprisingly, political. Gichin Funakoshi had died in 1957. Although Funakoshi had always opposed competitions, once he was dead there was nothing to prevent the JKA from organizing tournaments similar to those already held by Wado Ryu and Goju Kai karate groups. So it did. The Shotokai under Egami opposed this, and the result was a worldwide split. In Brazil, there was interest in competition, so the movement was toward Shotokan (competitive) and away from Shotokai (non-competitive). And, as a result, students of Chile's Humberto Heyden had to reintroduce Shotokai karate to São Paulo during the 1990s.

Meanwhile, Jiro Takaesu opened a Goju Ryu dojo in São Paulo in 1955 and Shikan Akamine opened a school teaching a mixture of Goju Ryu and Shuri-te karate in 1957. Nothing is known of Takaesu today, but Akamine's student Fernando P. Cämara still teaches in São Paulo today.

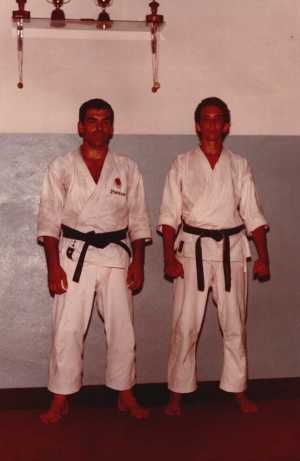

Shikan Akamine, early 1960s

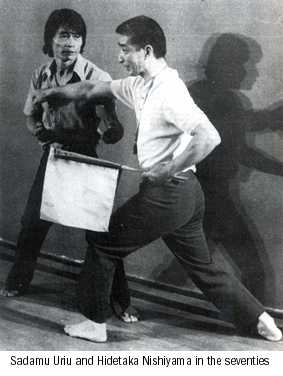

Finally, Yasutaka Tanaka and Sadamu Uriu, both of whom started teaching Shotokan karate in Rio de Janeiro within a month of each other in 1959, have claimed to be the first to teach karate in Brazil. Tanaka and Uriu are widely appreciated for their skill -- both have been coaches of the Brazilian national karate team -- and so there is no need for these exaggerated claims.

KARATE SPREADS THROUGH THE COUNTRY

Karate developed first in São Paulo and Bahia because that was where the most people of Okinawan and Japanese descent lived. During the late 1960s karate spread throughout Brazil and some famous champions of the 1970s were from Rio Grande do Sul and Paraná. Oddly, karate has never fared very well in Rio de Janeiro. Probably this is because Rio is the Gracie family's backyard, and so Gracie Jiu-Jitsu schools are everywhere. Be that as it may, most early developments stem from São Paulo and Bahia, and so our survey will concentrate on those states rather than elsewhere.

São Paulo

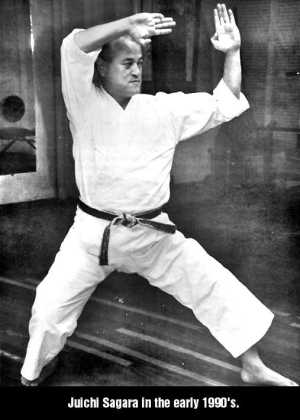

São Paulo's second generation of karate instructors appeared immediately following Harada's departure for Europe in 1963. Prominent examples include Tetsuma Higashino, Yoshizo Machida, Takeo Okuda, Ryuzo Watanabe, and Akio Yokoyama. The most famous, though, was the São Paulo restaurant owner Juichi Sagara; sadly, although an excellent teacher, most of his public reputation was due to his being the cousin of the Japanese professional wrestler Antonio Inoki. For some details of Inoki's career, see Donn Draeger, "Muhammad Ali vs. Antonio Inoki," http://ejmas.com/jcs/jcsdraeger_alivsinoki.htm.

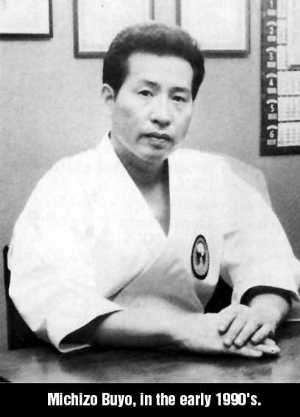

Until 1967, most Brazilian karate academies were Shotokan schools, the chief exceptions being Shinzato's Shorin-ryu, Akamine's Goju Ryu, and Takamatsu's Wado Ryu. Then Goju Ryu stylist Yasunori Yonamine and Wado Ryu stylist Michizo Buyo arrived in São Paulo.

Yonamine's three daughters subsequently became famous kata champions. Meanwhile Takamatsu and Buyo were actively involved in introducing competition into Brazilian collegiate clubs. This was considered innovative because until 1957 Shotokan karate had been non-competitive and therefore Brazilian karate training focused on kata rather than sparring. Wado Ryu, however, had been holding tournaments in Japan since the mid-1930s. The idea of tournaments met with favor in Brazil and by the early 1970s there were regular competitions throughout the country.

Meanwhile a Shotokan stylist named Tsuneyoshi Tanaka (not related to another Shotokan teacher named Yasutaka Tanaka) turned to Kyokushin Kai karate. At first he learned from books but later he went to Japan to study with Mas Oyama. When he returned to Brazil he brought a Kyokushin Kai instructor named Shojiro Ogawa with him, but the latter didn't last long. So in 1972 Tanaka invited another Kyokushin Kai instructor named Seiji Isobe to come to Brazil. The two evidently had a falling out because shortly after Isobe arrived, Tanaka gave up Kyokushin Kai for an offshoot called Seidokan. Isobe on the other hand has been the leader of Kyokushin Kai karate in Brazil ever since.

In 1978, Ademir Sidney Ferreira da Costa, a direct student of Isobe, became a world champion in Kyokushin Kai karate. This was in a youth division rather than adult, but as he was only sixteen, the feat made da Costa famous in Japan as well as Brazil. Following the death of Mas Oyama in 1994 da Costa started having trouble with Seiji Isobe and various would-be big shots in the Kyokushin Kai organization in Japan, so in 1996 he quit the Kyokushin Kai and started his own Brazilian association called Seiwakai. Seiwakai held its first championships in 1998.

All of these people in one way or another owe their status to the Japanese teachers and styles mentioned before. However, ego gets in the way and sometimes the organizations have feuded -- in São Paulo, a state team actually went on strike against the local federation, and in Bahia, there have been incidents of physical violence between rival schools. This conflict and ill feeling is very sad.

Bahia

Bahia is in the northeast of Brazil, and like many parts of the country it had a Japanese immigrants' colony. And there are also the usual undocumented reports of karate training there during the 1950s. So, during the 1960s a man named Mario Conceição, claiming to have learned from these legendary teachers, began to teach Gracie Jiu-Jitsu, wrestling, and rudiments of karate to students at the Ginásio Acrópole ("Acropolis Gymnasium") in the Bahian capital of Salvador.

Of more importance, however, was the Japanese immigrant colony in Bahia. Masahiro Saito, for example, was a Japanese engineer who came to Bahia as part of an agricultural settlement scheme. Having trained in judo in Japan, in Brazil he began studying karate from Koji Takamatsu, a Wado Ryu 5-dan who worked at the same agricultural project. Later Saito began teaching karate to the security staff of Petrobrás, which is Brazil’s state-owned oil company. In these classes, his students included Múcio Magalhães, and the soon-to-be famous Denilson Caribé.

Masahiro

Saito

Masahiro

Saito

Such teachings were nonetheless sparse and the teachers were not experts. Therefore karate might have vanished like the old rubber boomtowns were it not for a thin and very young (just 16 years old!) Japanese adventurer named Eisuke Oishi. Oishi was from a wealthy family in Japan but after an argument ran away to Brazil to find an uncle. He never found the uncle but was instead introduced to Dr. Ângelo Decânio, who owned the Ginásio Acrópole and was an important patron of sports in Bahia. Oishi wasn't even a black belt in Wado Ryu but he still began to teach a group of ten students who were fascinated by his speed and fighting skills.

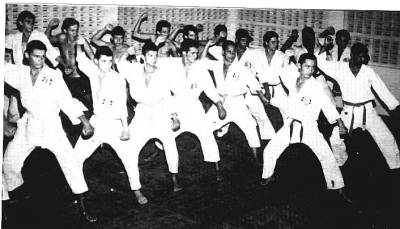

Eisuke Oishi is in the front; Denilson Caribé is first from the left. In the second row, fourth from left, is Ivo Rangel.

And, being young and without much formal instruction, of course he focused mostly on kumite, or free sparring. The young students were enthusiastic, to say the least, and the training at the Acrópole was quite violent and almost without rules. (The same situation occurred in Japan where rules were still in the making and not accepted by all.)

But after a short time, Oishi began to miss many classes and interest began to wane. Curious, one of the original ten, Denilson Caribé, set out to find out why, and soon discovered Oishi, very sick, living under the stairs in a cheap hotel because he couldn't afford to pay for a room. Caribé paid his debts, took him to his own home (unknown to his own father), and generally looked after him until he got better. Once healthy again, Oishi resumed teaching Caribé and other young men, many of whom were security guards for Petrobrás.

These were working class youths, and as said before their training focused on kumite. As a result this first group became very aggressive and combat-oriented.

In 1965, São Paulo hosted the First National Karate Integration Movement and the First Interstate Karate Tournament. Bahia took a team composed of Lazaro Gagliano, Denilson Caribé, Carlos Alberto Costa, Ivo Rangel, Renato D. Filho, and Renato Pereira, with Oishi as the coach. It listed its association as Wado Ryu under Akira Taniguchi of São Paulo, and the Bahia team took the first place trophy.

Oishi and his team returned to Bahia believing they knew all about karate. Then Kazuo Yoshida, the father of Bahia judo, told Caribé that he was living in a dream and presented him to Yasutaka Tanaka, a Shotokan teacher from Rio de Janeiro. Caribé visited Tanaka in Rio and was shocked to discover how little he really knew. So he and Oishi decided to join Tanaka's Shotokan group and it was Tanaka who promoted Oishi to shodan (black belt) and Caribé to color belt. (Until that time everyone in the Bahia group wore a white belt.)

Yasutaka Tanaka visiting Bahia. Seated front row -- Denilson Caribé (looking down), Yasutaka Tanaka, Masahiko Tanaka, and Yochizo Machida. Photo courtesy Raimundo Veiga and Isaías de Brito.

Shortly afterwards, Oishi returned to Japan, where, according to Ivo Rangel, he currently works for Sony. However, under the charismatic leadership of Denilson Caribé, the Bahia organization continued to spread and grow. For example, Caribé established ASKABA, which was the first karate organization in the Brazilian north/northeast. He was also founder of the Bahia Federation of Karate; co-founder of the Brazilian Confederation of Karate (CBK); technical director of the CBK; a pioneer of the teaching of karate to children; and the first to write a permanent column on karate for a Bahia newspaper. Unfortunately he died in late 1985, during a car trip to Vitória da Conquista in Bahia. He was getting ready to take his team to the Pan American championships and his passing was much mourned by the Bahian karate community.

Yasutaka Tanaka (L) and Denilson Caribé. Photo courtesy Raimundo Veiga and Isaías de Brito.

Nevertheless, it must be added that Caribé was also a figure of controversy. For example, he and his brothers acted as henchmen to their Japanese mentors, beating up rivals, invading "enemy dojo," and generally acting like gangsters. He was evidently proud of this behavior, too, as he confirmed those points in an autobiography that he published in the Brazilian magazine Do and in a Bahian newspaper. Furthermore, he was not especially open to compromise. For example, around 1972 or 1973, just as taekwondo was getting established in Bahia, its pioneer Lim Jung Do and his student Ubaldo Alcantara asked about arranging a competition between Shotokan and taekwondo. This would have been a first, but Caribé nixed that by refusing to compromise on rules -- the tournament would be run his way or not at all, and in the end it was run not at all.

A group photo of Bahia's first yudansha (black belt association)

Ivo Rangel da Silva is another important figure in the development of karate in Bahia. A contemporary of Caribé, he was responsible, even more than Caribé, for the strength of the Bahian competition teams. The reason was that as he got more successful, Caribé began concentrating on middle-class students whereas Rangel continued teaching karate to working class youth. So Rangel had the more combative students and they were soon winning all the local karate championships.

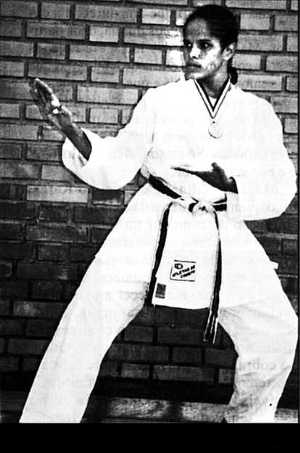

Ivo Rangel

CONTEMPORARY BRAZILIAN KARATE

In 1972, Luiz Tasuke Watanabe of Rio Grande do Sul became the first athlete from a western country to win a world karate championship. This was not a fluke, either, as the following year Watanabe took second.

Luiz Tasuke Watanabe

Five years later, in his book Best Karate, Comprehensive, Masatoshi Nakayama included a photo of the Bahia Karate Association. (It is on page 46 of the Brazilian edition.) The photo was taken at a seminar, and during that seminar Nakayama told the assembled karateka that what he saw in Bahia was at least as good as anything he had seen in the USA.

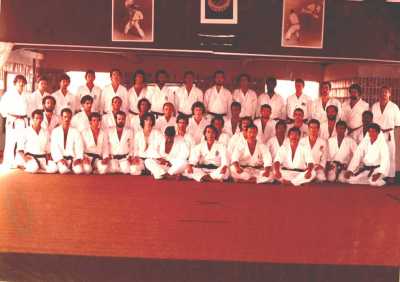

Photo taken during the visit of Masatoshi Nakayama to Bahia in 1977. Kneeling: Raimundo Veiga, Vilobaldo Pedreira, Denilson Caribé, Masatoshi Nakayama, Yoshizo Machida, Ivo Rangel, and Antonio Aderne. Photo courtesy Raimundo Veiga and Isaías de Brito.

The generation of karateka that followed also did well. For example, well-known international-level Brazilian karate champions include:

Ennio Vezzuli (left) with Isaías de Brito

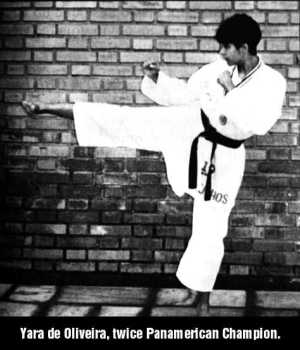

Not all the champions were male, either. For example, in 1999 Maria Cecilia de Almeida Maia became Brazil's first female world karate champion. Other well-known Brazilian female karateka include:

Maria Cecilia de Almeida Maia

And this despite Brazilian karate tournaments generally not being open to women until the 1980s!

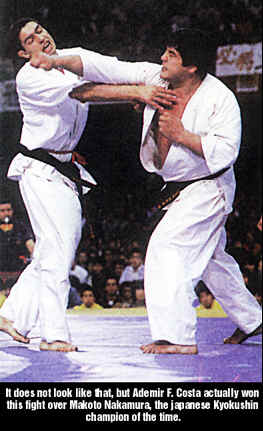

It is fair to acknowledge stylistic champions, too, especially those of Kyokushin Kai. Francisco Feitosa was a famous athlete and competitor who represented Brazil in Japan, and Ademir da Costa, who became famous for beating Japanese champion Makoto Nakamura, despite his not even being a black belt AND giving up sixty pounds. Glauber Feitosa also won some Kyokushin Kai tournaments in Japan, and one of today's greatest stars is Francisco "Chiquinho" Filho, who is a champion in Japan's K-1 style.

As for the future, well, there are some clouds on the horizon. The biggest is that some organizations are not very cooperative and continue to work apart from one another. Hopefully these politics won't affect the individual athletes too badly, but feuding is never good for a country's martial arts.

***

During the research involved in preparing this article one of the authors (Alcantara) interviewed Antonio Souto Aderne, who was one of Caribé's first students. Besides being a cultured, educated man (his profession is engineer), Aderne, who still lives in Bahia, is the founder of the Bahia Federation of Traditional Karate, which in turn is affiliated with Hidetaka Nishiyama's International Traditional Karate Federation.

People present at the founding of the Bahia branch of the International Traditional Karate Federation

Aderne believes that while Oishi was the pioneer of karate in Bahia, Caribé was the person most responsible for its growth, not just in Bahia but also in Brazil. Asked what allows Brazilian karateka to achieve recognition in international fighting competitions, he replied: nothing special, just "very hard training, a strong will and malicious strategy."

Antonio Souto Aderne

However, another reason may be karate's roots in Bahia. As noted above, the early training was very violent and it attracted mostly working class youths. So the interest in culture and kata were minimal, but the interest in kumite was high. And, as these young men lived in violent neighborhoods, they had motivation to excel in fighting.

Aderne Sensei is a tall man, with a strongly combative karate. And he is normally very serious. But then all of a sudden he surprises us with fantastic bits of humor such as this:

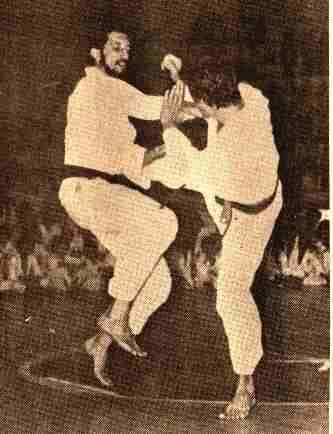

Aderne (left) in Brazilian National Championships

The Bahia team was participating in a tournament in another state. This was expected to be a tourist tour for the Bahia team, since it always won all the medals and trophies. On the day before the championship, the group went to a soccer field to have a last training. When they arrived, another group was waiting to see the Bahians' training. The Bahia coach, Alberto "Little Smoke" Fonseca, said he wouldn't train in front of the audience. Very seriously, Aderne Sensei said: "Nonsense, Little Smoke! We have put on our karate-gi. Now we must train!"

Fonseca Sensei replied, "If it's so important to you, why don't you lead our men?"

Aderne Sensei smiled and said, "Sure!"

He then went on, under the eyes of the other team, and said to his men: "Now, boys! Everyone running like gazelles, softly, and moving the arms, up and down, like butterflies..."

The other team was open-mouthed and couldn't believe their eyes. They left sure that all of Bahia's team was effeminate. And were trampled, next day, by Bahia's juggernaut...

Upon hearing that story, the visitor exclaimed: "Impossible, Sensei! Everybody knows that karate is for real men. There are no effeminates in it!" Aderne Sensei looked at his senior, Isaías de Brito, and said, with another of those soft smiles: "This guy is so deluded, Isaías…"

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Our work has been enriched by the unselfish contributions of Luiz Miele Sabonim (hapkido), Maurício Francischelli (aikido), Gilberto Antonio Silva, Antonio Souto Aderne (karate), Eckener Cardoso (karate), Ivo Rangel (karate), Isaías de Brito (karate) and many others whom we may have unjustly forgotten. Anyway, thanks to you all!

FOR FURTHER READING

Not everyone described in this article has a website, or is even mentioned

on one. For example, Eisuke Oishi was very young when he started teaching

karate in Bahia and today his status-conscious former students are sometimes

reluctant to admit that their first teacher was a teenaged brown belt.

Meanwhile the Japanese immigrants who lead most Brazilian karate associations

don't want to acknowledge the importance of native Brazilians such as Denilson

Caribé. Therefore information about Caribé and Oishi was

gathered mostly through interviews with Antonio Souto Aderne, Ivo Rangel,

Eckener Cardoso, and Isaías de Brito. For other instructors and

organizations named, try these sources.

Shinzato Sensei (Kobayashi Shorin-ryu)

From Bahia, Ubaldo Alcantara began training in jujutsu during the 1950s. "Unhappily," says Alcantara, "I was young and mostly interested in the physical part, so I never learned what his style was, but from what I have since gathered, it was Tenshin Shin'yo Ryu." During the 1960s he studied judo and karate, and then in the early 1970s, he began studying taekwondo and hapkido under Lim Jung Do. He has translated many taekwondo documents from English into Portuguese for the Brazilian associations; he was partially responsible for the Brazilian government recognizing taekwondo as an official sport and was an invited observer to the second World Taekwondo Championships in 1975. Today he is the vice-president of the Bahia Inter-Styles Taekwondo Federation and webmaster of the Portuguese-language aikido site http://www.egroups.com/group/aikido-lingua_portuguesa. Time permitting he also reads; his favorite authors range from Shakespeare to Lovecraft.

From São Paulo, Antonio Rodrigues is a former capoeira player, judoka, and karateka who is now an aikido instructor. He has lots of friends, and he likes reading and writing about the martial arts as much as he enjoys training in them.