Although immigrant Japanese had boxed in the United States since at least the 1880s, Seattle's James Yoshinori Sakamoto (1903-1955) was among the first Nisei (second generation Japanese Americans) to box professionally.

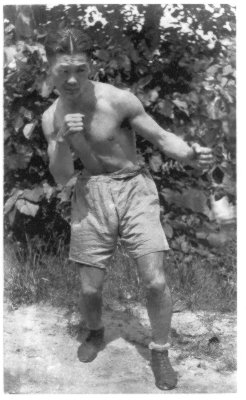

James Sakamoto, ca. 1925. Courtesy the Sakamoto Family.

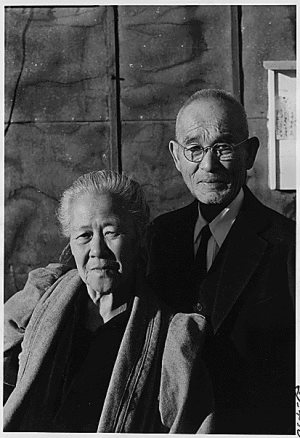

Sakamoto's father Osamu came to Washington State in March 1894. Osamu Sakamoto's first jobs were the usual immigrant jobs--working at a restaurant in Tacoma, working on a farm in Puyallup, sweeping sawdust at the Port Blakely lumber mill on Bainbridge Island. In 1897, having grown tired of working for other people, he opened his own restaurant in Seattle. Soon after, he gave up the restaurant for a hotel. "During his business career," said Osamu Sakamoto's obituary published in the Seattle Times on April 1, 1954, "he operated four hotels, three furniture stores, a small trucking business and vegetable stands. He retired in 1930, and his wife, Tsuchi, died in 1952."

Osamu Sakamoto, 80, and Tsuchi Sakamoto, 80, on their golden wedding anniversary, December 11, 1943. A War Relocation Authority photographer took this picture at Minidoka Relocation Center in Idaho. National Archives and Record Administration photo, ARC Identifier 539530.

Osamu and Tsuchi's son Yoshinori was born in Seattle on March 22, 1903. Yoshinori Sakamoto liked athletics, and so, around 1910, he took up judo at the recently organized Seattle Dojo. According to Frank Chin (2002: 109), the club's senior instructor, Tokugoro Ito, "told young Sakamoto he would do better boxing."

During high school, Jimmie, as his American schoolteachers called him, played varsity football, and during his senior year, the Franklin High School yearbook (Tolo, 1921: 153) described him as the "best line player ever seen in Seattle high school football." His friends at Franklin included Eitaro Suzuki, a judo black belt who wrestled for Japan during the 1932 Olympics.

Although some sources say that Sakamoto graduated from high school in 1920, the Franklin High School yearbook includes him in the graduating class of 1921. In any event, between 1920 and 1923, Sakamoto was active in the Japanese community's efforts aimed at blocking new anti-Asian legislation in Washington State. This was a losing cause. As Matthew Klingle has noted (1997), "The 1889 state constitution, in Section 33 of Article II, already prohibited resident aliens from owning land. In 1921 and 1922, the rule was extended to leasing, renting, and sharecropping of land."

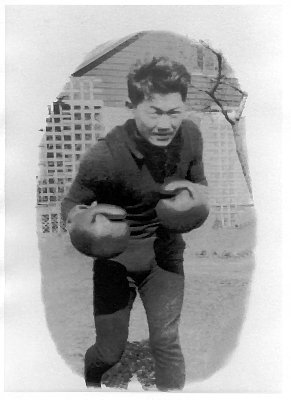

In 1923, Sakamoto moved to Princeton, New Jersey, where he attended college and worked as English-language editor for a Japanese newspaper called Nichibei shuho ("Japanese-American Commercial Weekly"). He also boxed, both with a university club and at the Japanese Christian Institute.

Around October 1925, Sakamoto started boxing professionally. His first known opponent was Gene Martini, and the result was a win for Sakamoto, via knockout in the first.

Such successes caused the Honolulu Advertiser (December 21, 1925) to describe Sakamoto as "a featherweight boxer, who is making good in New York rings." Unfortunately, Sakamoto's manager regularly matched him against heavier boxers, thereby improving the betting odds. Consequently, Sakamoto took some heavy blows, suffered detached retinas, and started going irreversibly blind following a fight with Clark Anderson in Utica, New York, on December 20, 1927.

Sakamoto's cousin Toshio Yamanaka recalled (letter, September 1997), "I was still in grammar school when James came back from New York and his father went to the Union Station to pick him up. His father told us that James was hanging on to a post weeping as he couldn't see." Osamu Sakamoto took his son to ophthalmologists; eventually, he even took him to Japan to see doctors. There was nothing to be done: Darkness was falling.

James Sakamoto, ca. 1925. Courtesy the Sakamoto Family.

However, Sakamoto was unwilling to stay down for the count. In the words of his daughter Marcia (personal correspondence, January 7, 2004), while he could still see a bit, he blindfolded himself "and learned his way up and down stairs and around the house by counting his steps. He also taught himself to type and learned Braille." Sakamoto also borrowed some money from his father, and on January 1, 1928, he started a four-page weekly newspaper called the Japanese-American Courier. His typesetters included his wife Misao, and during the mid-1930s, his writers included Bill Hosokawa, a future Denver Post editor. As Hosokawa remembered his first newspaper job, "The newspaper was in a very precarious financial situation, and they needed all the help they could get. I went to see Jimmy. I said, 'I want to work here.' … And he said, 'We can't pay you, but you're welcome to work here.'" (Go, 2003)

Although the Courier never really got out of its financial straits, it continued to be published until April 1942. Today, the paper is remembered mostly because it was North America's first Japanese community newspaper to be published exclusively in English. However, by sponsoring baseball and basketball leagues, Sakamoto and the Courier did more than just document community history--they also helped create it. Explained Sakamoto's daughter Marcia (personal correspondence, January 7, 2004), "Dad felt that the young people in the community needed constructive outlets for their energy, and to avoid divisiveness he and the Courier sponsored the athletic leagues which became focal points for the community."

On the editorial pages, Sakamoto took a more controversial stance. "Today," said Bill Hosokawa (1998), "he would be called a community activist; back then, he was preaching militant, unquestioning loyalty to the United States to second-generation Japanese Americans, the offspring of immigrant parents." Toward this end, in 1929, Sakamoto helped create the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL), and from 1936-1938, he served as the organization's national president.

Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, Sakamoto became a leader of the JACL's Emergency Defense Council, which was dedicated to proving through its actions that Japanese Americans were loyal to the US rather than Japan. "We cannot fail America," he wrote in his paper on December 8.

In February 1942, Sakamoto traveled to California to testify against Lieutenant General John L. DeWitt's plan to forcibly relocate Japanese Americans. According to Sakamoto's daughter Marcia (personal communication, January 9, 2004), "He was informed that General DeWitt's orders had already been implemented and that he should return to Seattle."

Three generations of Sakamotos at Minidoka, December 1943. Courtesy Toshio Yamanaka.

Perhaps he feared what would happen to his community if DeWitt's orders were not obeyed. Perhaps he believed, as he testified in California, that "loyalty demands that orders, no matter what, be obeyed, willingly and efficiently" (Hohri, August 1990). Or perhaps he was simply confident that, given time, the panicked American government would return to its senses. In any case, Sakamoto urged acquiescence to relocation rather than resistance, and at the Puyallup Assembly Center, he even accepted a leadership position in the camp administration. Many Japanese and Japanese Americans resented this pro-government stance (Masaoka, 1982; Mudrock, 1997), and so he never again played a significant leadership role in the Japanese American community.

After the war, Sakamoto returned with his wife and their children to Seattle, where he eventually found employment as a telephone solicitor for St. Vincent de Paul. He walked to work, crossing streets with the bells, and he died in the street on December 3, 1955, after being struck by a car while crossing Fairview Avenue North.

His last words were, "I heard the bell."

For further reading

Akichika, Yutaka Nishitani. 1979. Nishitani Families in the United States. Tokyo: Self-published.

Chin, Frank, editor. 2002. Born in the USA: A Story of Japanese America, 1889-1947 (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman and Littlefield)

Daniels, Roger. 1997/1998 (Winter). "The Exile and Return of Seattle's Japanese." Pacific Northwest Quarterly 88: 166-173. http://www.washington.edu/uwired/outreach/cspn/html/98winter/article2.html

Go, Kristen. 2003. "Q&A: Bill Hosokawa--Survivor, Pioneer." Maynard Institute for Journalism Education. http://www.maynardije.org/news/features/011109_hosokawa

Hohri, William. 1990 (August). "The Epistolarian." http://ohp.fullerton.edu/Epistolarian/eplhtm/EP9008.htm

Hosokawa, Bill. 1982. JACL in Quest of Justice. New York: William Morrow.

Hosokawa, Bill. 1969. Nisei: The Quiet Americans. New York: William Morrow.

Hosokawa, Bill, with Tom Noel. 1998. Out of the Frying Pan: Reflections of a Japanese American. University Press of Colorado; extract published at http://print.google.com/print/doc?isbn=0870815008

Ichioka, Yuji. 1986/1987. "A Study in Dualism: James Yoshinori Sakamoto and the Japanese American Courier, 1928-1942." Amerasia Journal 13.2: 49-81.

Japanese-American Courier January 1, 1928-April 24, 1942. Microfilm.

Klingle, Matthew W. 1997. "A History Bursting with Telling: Asian Americans in Washington State." Center for the Study of the Pacific Northwest. http://www.washington.edu/uwired/outreach/cspn/curaaw/main.html

Masaoka, Mike Masaru. 1982. "Statement of Mike Masaru Masaoka." Conscience and the Constitution. http://www.pbs.org/itvs/conscience/who_writes_history/looking_back/02_masaoka.html

Mudrock, Theresa. 1997-2003. "Camp Harmony Exhibit." http://www.lib.washington.edu/exhibits/harmony/Exhibit/default.htm

Mullan, Michael L. 1999. "Ethnicity and Sport: The Wapato Nippons and Pre-World War II Japanese American Baseball." Journal of Sport History 26.1: 82-114. http://www.aafla.org/SportsLibrary/JSH/JSH1999/JSH2601/jsh2601e.pdf

Niiya, Brian, editor. 1993. "Sakamoto, James." Japanese American History: An A-to-Z Reference from 1868 to the Present. New York: Facts on File: 300-301.

Regalado, Samuel O. 1995/1996 (Winter). "'Play Ball!': Baseball and Seattle's Japanese-American Courier League, 1928-1941." Pacific Northwest Quarterly 86: 29-37.

Smithsonian Institution. 1990-2001. "A More Perfect Union: Japanese Americans and the U.S. Constitution." http://americanhistory.si.edu/perfectunion/non-flash/removal_process.html

Svinth, Joseph R. 1999 (Summer). "A Celebration of Tradition and Community: Sumo in the Pacific Northwest, 1905-1943." Columbia: The Magazine of Northwest History, 13.2: 7-14. An updated version appears at Journal of Combative Sport, 2002, http://ejmas.com/jcs/jcsart_svinth_0202.htm.

Takami, David A. 1999. "James Sakamoto (1903-1955)," Seattle/King County History Link.org. http://www.historylink.org/_output.CFM?file_ID=2050

University of Washington Special Collections. 2003. "Guide to the James Y. Sakamoto Papers, 1928-1955." http://www.lib.washington.edu/specialcoll/findaids/docs/papersrecords/SakamotoJames1609.xml