Preface

The first portion of this article appears at http://ejmas.com/jalt/jaltart_noble_0502.htm. Along with my articles on Yukio Tani and Youssuf Ishmaelo, these are chapters from the book I’m trying to put together on turn of the (nineteenth) century jujutsu and professional wrestling. I never intended to write a book, but the interest of the subject took hold, and it somehow seems that the book itself wants to be written. At any rate, when I began to write on these subjects, help and material began to flow my way from some excellent historians and researchers.

I want to acknowledge my use of material from Joseph Alter’s historical essays on Gama, as they were an invaluable source for Gama’s pre-England career. Grateful thanks also go to Robert W. Smith, who first stirred my interest in Gama with his 1963 Black Belt article, who supplied me, just at the right time, with a copy of Muzumdar’s Strong Men Over the Years, and who allowed me to quote extensively from his Stanislaus Zbyszko letters; to wrestling historian Mark Hewitt; to Michael Murphy, who has been amazingly generous in sharing material from his collection; to John Spokes, for the loan of his old editions of Health and Strength; to Joseph Svinth for sending me copies of Ernest Sodergren’s clippings on the Great Gama (which he in turn received from Nadeem S. Haroon); and to the British Library and British Newspaper Library. Thanks are also due to Joe Roark, for obituary material relating to Hackenschmidt and Zbyszko, and Balbir Singh Kanwal, for Indian newspaper accounts relating to Gama and Zbyszko.

Hopefully that’s included everyone, and if anyone has further information on Gama and the other great Indian wrestlers of the early twentieth century, please contact the editor at jsvinth@ejmas.com.

IV

To prepare for his match with Gama, Stanislaus Zbyszko went into training

at Rottingdean, under the supervision of Bill Klein. He rose at six, worked

out for an hour with his younger brother Ladislaus (Wladek, I presume),

then went for a walk and a swim before breakfast at nine. After an hour’s

rest he took a long walk over the hills ("ten to fifteen miles") and the

rest of his practice consisted of wrestling, skipping, boxing, and working

out with the medicine ball. A thorough massage ended the day’s training.

Supper was at eight, and bed at nine.

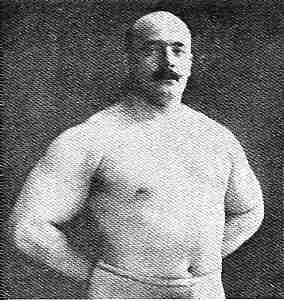

Stanislaus Zbyszko, ca. 1909

Zbyszko trained at Prinn’s, the local Rottingdean blacksmith, who had a well-fitted out gymnasium, but a lot of his training was done in the open air, and since the weather was good, he had acquired a tan and looked fit and in good condition. Klein had watched his diet, so that Zbyszko’s weight was reported as down to 17 stone (238 pounds), and he may even have gone down below that. In contrast to the match with Poddubny, where weight and strength would have been vital factors (and where Zbyszko pushed his weight over 250 pounds), in a match with Gama, quickness and conditioning would be more important, and so Zbyszko was working on reducing his weight. The weights for the Gama-Zbyszko match were never announced, although it is generally stated that the Pole was up to 4 stone (56 pounds) heavier. I doubt that: the photos of the two men shaking hands for the match show little apparent difference in size, although clothing hides their true physical condition. Zbyszko’s face does look lean, so he may well have been as low as 230 pounds, maybe a bit more. Gama’s weight is usually given as 200 pounds, but if he was more than that, then the weight difference would fall well below the 50-pounds-plus usually quoted. Zbyszko told Robert W. Smith that the difference was only ten pounds. I would guess between 20 and 30.

Gama was training at Surbiton, going through his usual routine of thousands of dands and bethaks and wrestling with his compatriots. Around this time the Indians were showing at the Alhambra Theatre, doing some exhibition work, and on August 23, 1910, the report of their appearance read:

That was an interesting point about Gama’s ability on the ground, especially considering what was to follow, and a similar comment was made in The Sporting Life’s preview of the upcoming bout with Zbyszko. "As Gama has not had to wrestle much on the ground, it may be that in ground wrestling he is not such an accomplished exponent as in an upright position." One point mentioned several times in the contemporary papers was that in India one shoulder down counted as a fall, so this variation in rules may have made a big difference to Gama when he came to wrestle in Western arenas.

Some of the initial enthusiasm for Gama’s victory over Roller seemed

to have worn off, particularly because it now seemed that he had had to

work hard to pin a man who was suffering from two broken ribs. It has to

be said, though, that apart from one instance when Roller winced from a

Gama waisthold, "The Doc" showed little sign of his injury during the match.

And I may be unfair and too cynical, but when you read the background of

Benjamin Franklin Roller, you begin to question whether he actually had

any ribs broken at all.

Benjamin F. Roller

Joseph Svinth sent me some research he had done on Doc Roller. Several clippings from that era refer to the Doc’s unfortunate habit of being injured in wrestling bouts. In May 1910 his left shoulder was badly wrenched in losing to Zbyszko in Buffalo, and the Seattle Times commented that "Roller has not been making much of a showing in his matches of late. He usually gets hurt and loses, and he puts in the time between various hospitals nursing his hurts and fighting off attacks of blood poisoning." The same paper reported on November 16, 1912: "Dr. Roller has had his ribs broken again. Doc has had ribs broken in London, Seattle, Philadelphia, and several other seaports, both in football and in wrestling, and last night honored Ottawa, the capital of Ontario, by having his slats cracked there. He was wrestling a large, well-fed Belgian named Constant le Marin."

This was the same Doc Roller who was one of the busiest wrestlers in the game, and who told the Seattle Times in December 1910 that he was wrestling every night, and had had 21 matches in November. It’s hard to reconcile that level of activity with someone who was regularly injured (broken ribs take at least 4-6 weeks to heal), and so it sounds like the saga of the broken ribs was a story line Roller regularly trotted out for dramatic effect and to emphasize his gameness.

In the Gama contest he may for once have actually suffered broken ribs, but there is an element of doubt, and that makes any judgment on Gama’s performance problematical. On the whole, experts seemed to think that Gama would beat Zbyszko in their upcoming match, and some people may have been swayed by Gama’s boastful promise to throw the Pole three times in an hour, but there was still quite a bit of uncertainty about the outcome.

V

The great wrestling match for £250 a side and the John Bull Belt started at four in the afternoon on September 10, 1910. The venue was the 68,000-seat stadium built for the 1908 Olympics at Shepherd’s Bush. The crowd was estimated at 12,000, although they were lost in the huge stadium, most of which looked empty. The referee was the well-known Jack Smith.

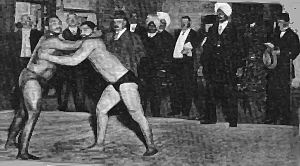

Zbyszko, Jack Smith, and Gama, 1910

Within a minute of the match starting, Zbyszko was taken down, and took up a defensive position, where he remained for the rest of the match. Gama tried a half nelson, and then a wristlock, but Zbyszko seemed too strong, and after a quarter of an hour, the men had hardly moved from their initial positions. After half an hour, there was a brief struggle "like a rugby scrimmage," but nothing resulted and Zbyszko went back to his defensive position, with Gama trying unsuccessfully to turn him over. At intervals Gama would try a waist hold, a quarter nelson, a half nelson, but his efforts were futile and it seemed that, even in these early stages of the match, he had pretty much run out of ideas.

Almost all of the attacking work was done by Gama. He tried hard but he was ineffective against an opponent who wouldn’t wrestle in open play. Zbyszko remained strong, however, and at one point "rearing up from the ground to his hands and knees he momentarily precipitated Gama into the air." But then he again returned to his passive defence and the wrestling stopped once more. As the bout moved into its second hour the pattern remained the same: "At long intervals Zbyszko would wake up, there would be a stiff tussle for a few minutes after the manner of a rugby scrimmage, but the instant the Gallician detected the lightest sign of danger he would return to an entirely prone position." For long periods Zbyszko would simply remain stationary, Gama trying to turn him over, but without achieving any result.

On the two-hour mark, Zbyszko sprang to his feet and managed to get a reverse waist hold on Gama. He lifted him slightly and both went down together, but then Gama was back on top and the monotony continued. A little later the two men were on their feet for a few seconds as Zbyszko tried for a waist hold, but Gama was "strong and nimble" and evaded the attack. Gama attempted a crotch hold but Zbyszko was too heavy for him.

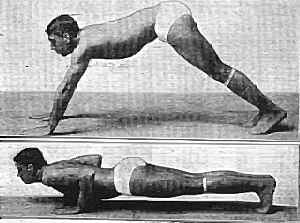

Indian wrestlers preparing for a throw.

A halt was called after 2 hours 35 minutes, with Zbyszko in that defensive position on all fours, and Gama on top trying to work some kind of a hold, the positions they had held for most of the bout. Since, under the terms of the match, there had to be a result, it was announced that the men would wrestle to a finish at the Stadium the next Saturday, September 17. The Sporting Life estimated that in the whole two-and-a-half hours, there had been maybe one and a half minutes of wrestling. It headlined its report, "Fiasco at the Stadium," and described the bout as "a miserable farce." It went on to say:

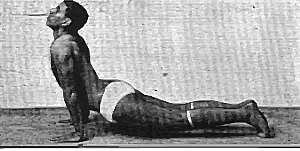

Gama

But Gama did not escape criticism. Everyone recognised that, throughout the two and a half hours, he had tried honestly to overturn Zbyszko: it was just that his efforts had been ineffective ("wholly useless," as Percy Longhurst later recalled). "Gama was frankly disappointing," said The Sporting Life. "He evinced a woeful ignorance of the technicalities of ground wrestling. His attack was all of one kind, and continued in spite of its non-success." There was general agreement that, although Gama was quick, he lacked skill and variety in groundwork, and Zbyszko was just too strong for him. In a letter to The Sporting Life, Henry Werner wrote that "Gama’s knowledge of the mat is not far above that of a novice and his holds were broken with the greatest ease. Imam Bux would be a far superior opponent to Zbyszko than Gama as a match would very quickly prove."

So the reaction to the match was almost wholly critical, and yet there was a handful of people who were able to look at it from a different perspective.

Moses Rigg, a wrestler himself presumably, wrote that he was sorry to have missed a genuine wrestling bout – he had been expecting an arranged match and had therefore given it a miss. He thought that the abilities of each man had neutralised the other. He wrote, "I want to know from wrestlers – for no one else who has not gone through the mill can tell me – what could these heavyweight men do, in their fashion, that they did not do? …As for Mr. Zbyszko, I believe he did all that such a fat man could do or be expected to do – ‘Make it a draw’."

Similar comments came from the magnificently named Baron Helmuth von Knobelsdorf-Brenkenhoff, who was fairly well known in wrestling circles of the time. "When I bought my ticket," he wrote, "I expected to see no ‘wrestling’ as I knew that it was a straight match. People who know only a little of wrestling know too well that they can never expect exciting bouts in straight heavyweight wrestling. Certainly in fake wrestling and exhibition bouts both competitors try to bring themselves into most impossible positions and come out of even more impossible ones, thanks to the previous ‘arrangement’. I do not want to mention names, but I have witnessed two well known champions wrestling for three-quarters of an hour and going six times over the footlights among the audience, taking the referee with them on one occasion. The audience took this game as most serious." The Baron said that both Gama and Zbyszko had "tried their best in their own way" and pointed out the irony that, although it was the sporting papers who had called so loudly for straight wrestling, now that such a contest had taken place, they called it "disgusting."

Indian wrestlers demonstrating leg throw from inside

Anyway, the two men still had to wrestle to a conclusion the following Saturday, September 17th. At the appointed time, Gama turned up with his entourage, but – no Zbyszko. His name was called several times, but he had already left the country, supposedly because his mother was seriously ill, although there was a rumour that he was wrestling in Vienna. Again he was vilified, and there were demands that he never be allowed to wrestle in England again. Anyway, Gama was declared the winner by default, and Horatio Bottomley, the owner of John Bull magazine, presented him with the 100-guinea "John Bull" belt and the £250 stake. Bottomley praised Gama’s sportsmanship and the beneficial influence of the Indians on British wrestling. He said that if Gama were to win two more championship matches the belt would become his personal property.

A little later Health and Strength carried the comments of the two wrestlers themselves. The editor went to see Gama at his training quarters at the Oak Hotel, Surbiton, and talked to him through an interpreter. Gama, he noted, had taken to wearing a bowler hat occasionally, "and very handsome and dignified he certainly looks." The Indian champion said he was sorry he had to win in such a way, but it was very difficult to deal with someone who just wouldn’t wrestle – and here he compared Zbyszko very unfavourably with John Lemm – and he was sure that he would have beaten Zbyszko if the contest had been continued on the 17th. He felt that Zbyszko knew this, and that was why he had fled London.

"You have no idea," said Gama, "how handicapped I was in my match with Zbyszko by my ignorance of the English language."

I will never, under any circumstances, wrestle Zbyszko for a money match again, but as I am anxious to prove my superiority to him, I’ll tell you what I will do: I’ll wrestle him in London any time that he likes, in the open, and on a green (not on a mat, like a bed that positively tempts a man to go to sleep on it). I’ll wrestle him thus for no stake at all, and without a referee, the proceeds to go to charity.

During my appearance here (Galicia) my name was made so bad in the papers by jealous and lying enemies that I broke off my engagement, and I will probably never wrestle in my native country again.

***

And then, almost before anyone realised, they had gone: packed their bags and returned to India. The reasons for the departure of Gama and the troupe were unclear, but it was said to be due to the problems in making matches and so on. Some reports implied that the Indians had been "driven home," although Herbert Turner was sceptical about that. He had heard that Benjamin, the group’s manager, had accepted an offer of £1,000 for a series of engagements in India, and that he would also be making money from the Eastern rights to the film of the Gama-Zbyszko match. Turner added the information that the gate receipts for that match amounted to £749, that Zbyszko received nothing, and "Gama did not receive a seventh part of this amount."

There was another chapter still to be played out in this story of Indian wrestlers and wrestling. In April 1911 Benjamin brought over another group of wrestlers, including Ahmed Bux, who had been with the 1910 troupe, but who had never wrestled a competitive match on that visit. The usual challenges were thrown out, with Hackenschmidt and Gotch being specifically mentioned. They had no intention of responding, and according to some reports Hackenschmidt was retired anyway, but in May a challenger did come forward, an "unknown" who subsequently turned out to be Maurice Deriaz, one of three famous strongmen brothers.

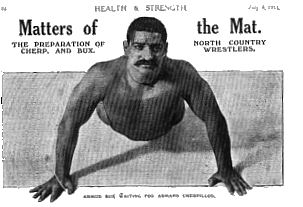

"Ahmud Bux waiting for Armand Cherpillod," Health & Strength,

July 8, 1911

The wrestling season was flat and it seemed that interest in wrestling was dying down, so this match was a welcome boost to the sport. It was, in fact, the first big competitive match since Gama vs. Zbyszko, and to stop any repetition of that "lamentable episode," it was decided that the referee would be given the power to disqualify a man "unduly lying on the mat and refusing to work." It was also decided that there would be no time limit to the match; it would be for the best of three pin-falls, catch-as-catch-can style, fifteen minutes rest between falls; for £50 a side and the best purse offered – 70% to the winner and 30% to the loser.

Maurice Deriaz was 25 years old and a real pocket Hercules: a heavyweight who stood only 5 foot 4-1/2 inches, a shorter version of Hackenschmidt in physique, and if anything even more densely muscled. Although probably better known in England as a weightlifter, he told Vivian Hollender (in 1911, when he arrived in England for the Ahmed Bux match), that he had been wrestling for eight years. Most of that was on the Continent in the Greco-Roman style, although recently he had been wrestling in America in the catch-as-catch-can style, and had beaten John Lemm, drawn with Zbyszko, and stood an hour with the bigger and heavier Hackenschmidt before going down to a fall. Deriaz was tough. He had a knife scar on his left side from a time he had wrestled in Madrid. As usual, he had issued his open challenge, and threw the first challenger in less than a minute, and then another, a 300-pounder. For some reason that caused a minor riot and Deriaz was knifed by one of the mob. The scar was still plainly visible when the doctor examined him for the Ahmed Bux contest.

Ahmed Bux was described as another great Indian champion, perhaps even cleverer than Imam Bux. He was 25 years old, 5 foot 8, and around 14 stone (196 pounds). Like Gama he was said to be very quick, clever, and a non-stop worker, "a man who never acts on the defensive… In practice he wrestles and exercises with his eight compatriots every day. They do not use dumbbells or clubs or apparatus of any description and they never vary their daily routine in the least."

The match took place on May 24 before a rather meagre crowd at the Crystal Palace, where "The Festival of Empire" was then being held. Deriaz looked rather tense, unsmiling, and determined, while Ahmed Bux was smiling easily. "The mighty arms and chest and limbs of Deriaz looked most impressive… Ahmed Bux looked for all he world like a bronze statue of exquisite workmanship… but his muscles pulsated with nervous energy."

As soon as the match started there was only one man in it as Bux’s speed carried Deriaz off his feet: after some preliminary sparring the Indian went in to take the Swiss round the waist and put him on his back. Deriaz struggled, but the throw was so quick he had no time to bridge, and he was quickly pinned. Referee Vivian Hollender tapped Ahmed Bux on the shoulder to give the fall in the amazing time of 66 seconds.

There was a 15-minute rest during which Deriaz and his manager retired to the dressing room while Ahmed Bux remained in his corner, calmly waiting. When the second bout started a determined Deriaz went for the leg but Bux was too quick. Then the Indian caught Deriaz in a body hold and again threw him on the mat. Deriaz tried a crotch hold, Ahmed Bux countered and almost turned him but this time the Swiss was determined not to get caught and twisted onto his stomach. He tried to get onto his hands and knees and at one point got a hold on Bux, but then again he was turned over and was forced to bridge to prevent the fall. Gradually, though, his right shoulder was forced down – and then his left, giving Ahmed Bux the second fall and the match after another 3 minutes 19 seconds of wrestling.

Deriaz felt bad about the loss, but he took it well, telling Health and Strength that "I’ve been beaten by a better, quicker wrestler and a stronger man, and though disappointed at the result I am not ashamed of it. I thought I was stronger than he, but now I know that I am not. Those arm rolls of his were terrible and, try as I would, I could not resist them. He is the strongest wrestler I have been up against in all my life." The reporter for the magazine also observed that Deriaz had drawn with Zbyszko and stood up for an hour and a half against Hackenschmidt, and so, he concluded, it was a matter of "simple arithmetic" to conclude that Ahmed Bux would also beat Zbyszko and Hack.

Indian wrestlers demonstrating arm bar with wrist lock

The Bux-Deriaz contest was a slight disappointment, it seemed, because of its brevity, and it being "so terribly one sided, more one sided than anyone expected." Ahmed Bux took the victory in his stride, saying only that Deriaz was a very strong man, while Benjamin appealed to anyone who would listen that he now wanted a match with Hackenschmidt, although, as one reporter commented, "I am sure he would like to, but this is not easy."

It was a rerun of the Imam Bux – John Lemm contest, and it must have scared off most prospective challengers, but Deriaz’s manager Ernest Delaloye soon came up with another opponent for Ahmed Bux, another Swiss as it happened, Armand Cherpillod. The contest was arranged for July 10 at the Oxford Music Hall.

Cherpillod was a well-respected technician, though some had doubts about his temperament. He had visited England as far back as 1902 when he had won a Coronation wrestling tournament (Greco-Roman style) at the National Sporting Club. It was rumoured, with what truth I have no idea, that in a private bout he had once thrown Hackenschmidt in three minutes. Cherpillod was respected as a catch-as-catch-can stylist, and he had also studied jujutsu, and had even written a book on it. He was supported by Peggy Bettinson, the manager of the National Sporting Club, who had been an admirer from that 1902 tournament. Cherpillod was 34 years old and weighed around 14 stone (196 pounds).

Armand Cherpillod

Unfortunately the match, when it took place, was another one of those fiascoes that seemed to plague professional wrestling around this time, and it was all over in four minutes. There was a curious preliminary to the actual wrestling when R.B. Benjamin, Ahmed Bux’s manager raised a couple of objections: "This gentleman caused considerable delay by first objecting to the resin with which Cherpillod had rubbed his feet, and when that had been removed by finding fault with the Swiss’ fingernails, which had to be cut and trimmed with a pair of Tom Pevier’s scissors."

The match started well enough, if cautiously. Bux got a waisthold that Cherpillod broke, and then the Swiss tried for the legs and failed to secure a grip. Soon Bux got behind, and Cherpillod tried one of his "clever dodges," striking his leg out sideways to try and hook Ahmed Bux’s foot and take him to the ground. But this time it didn’t work as the Indian parried the move so cleverly that it was Cherpillod who was brought down. Twice he just managed to rise but Bux retained his hold and the men went down to the mat with the Indian on top.

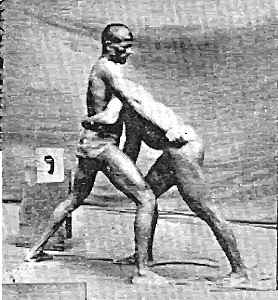

Kala (left) and Ahmed Bux. The photographer for Health and Strength

had arranged with the wrestlers to take some photos after the match, "but

Armand Cherpillod refused to face the camera then." (Health & Strength,

July 15, 1911)

Cherpillod, apparently, claimed he had been fouled. Some observers, such as Cyril F. Upton, who reported the contest for Health and Strength thought that Ahmed Bux had used an illegal jujutsu hold, although he did not intentionally foul. Monte Saldo said it had been a jujutsu hold, "though not a well known one." Mr. Elliott, the referee, said that the hold had been perfectly fair, and he made that judgement with thirteen years of experience in jujutsu behind him. In any case, Cherpillod was branded a "quitter," even being criticised by a supporter like Peggy Bettinson. "He has no heart," said Bettinson. "I do not like to hear a man squeal as he did, and he might at least have had another try."

This second win of Ahmed Bux seemed to scare off any other challengers. "Wrestling seems in a very bad state," commented Vivian Hollender, "inasmuch as the quicker a man wins and the more business-like his methods the less chance he gets of future matches." So although Benjamin had plans for Ahmed Bux to wrestle Hackenschmidt and Gotch, Bux’s career stalled, and those plans were never realised.

In mid-July, a new batch of Indians arrived in England, including the highly respected Gulam Mohiuddin. Although only around 13 stone (something over 180 pounds), he challenged all heavyweights. No matches occurred, but a couple of months later in France, in what was the last fling of Indian wrestling in Europe, Mohiuddin met Maurice Gambier, the French champion. This match, which took place in Bordeaux in a bullfight arena before a crowd of 5,000, was in the French Greco-Roman style, and yet Gambier was thrown twice in five minutes. Gulam Mohiuddin had only a few days to accustom himself to Greco-Roman wrestling, so – if this was a genuine match – his was a terrific performance, as good as any of the other Indians in their better known English victories.

VI

As far as I know, that was the last significant competitive match fought by the Indians in their prewar incursion into British and European wrestling arenas. Others came later, but the days of legendary victories were gone and they made little real impact. That may have been due to a decline in the general standard of Indian wrestling, though a more important reason was that professional wrestling was now a totally worked environment. There simply was no place for professional wrestlers who wanted to engage in real matches, and as the performances of the Indians had shown all too well, genuine wrestling bouts were often too short (as with Imam Bux vs. Lemm, and Ahmed Bux vs. Deriaz), too long and boring (Gama vs. Zbyszko), or otherwise unsatisfactory (Ahmed Bux vs. Cherpillod). For the growth of professional wrestling in its modern form, the product had to be managed and outcomes controlled.

Back in the early 1900s, it seems, you could still have genuine contests, though they weren’t all that frequent and the Indians did have difficulty in getting competitive matches. Gama, Imam Bux, and Ahmed Bux did make an impact, but it seems that they often had to work against the vested interests of pro wrestling: the promoters, managers, wrestlers, theatre owners, and to some extent the public themselves, all of whom wanted "a show." That’s not to say that the Indians were on some kind of crusade – even Gama, in the later years of his career, showed little inclination to put up his own crown against new challengers – but they were dedicated wrestlers who trained hard, and they wanted to wrestle; and Gama definitely had aspirations to be recognised as the greatest wrestler in the world.

In that respect, the visits of 1910 and 1911 didn’t fulfill their promise: the Indians made waves, but mostly they were unable to get the major matches they wanted, and their appearances had little long term effect on professional wrestling. They were certainly respected for their abilities, and were given full credit for their victories over Roller, Lemm, and Deriaz, and yet an authority like Count Vivian Hollender could still feel that they were not given the welcome they deserved:

A more common view, though, was that expressed in a letter to the magazine from a John Moore. In praising the Indians, he wrote, "They will meet all comers, not waiting for a large sum of money; there is no hugging the mat, no resting, no fake. Let the best man win, whatever his colour or nationality!"

This was an age, of course, which thought in terms of race, and the question was always there. It often expressed itself as a concern that the Indians’ crushing victories over Western opponents might indicate that these "dusky subjects of the British Empire" were actually representatives of a physically superior race. When the editor of Health and Strength concluded his report on the Ahmed Bux/Armand Cherpillod match, his last paragraph was a lament on the feebleness and lack of enterprise of British wrestlers:

‘We acknowledge the fact, and yet we would like to see one of our own race beat him. Is there none to be found? Surely – surely there must be someone who could do it. In this great game of chess, will the dark pawns sweep the board all the time?’

‘Maurice Deriaz was game, but not a wrestler; Armand Cherpillod was a wrestler, but not game. Where is the man who is both, and strong to boot?’

‘Let him COME FORTH.’

‘I do not grudge the Indians their victories; I only want to see our race victorious too."

To be continued.