Copyright © Graham Noble 2002. All rights reserved.

Editor’s note: The term "Indian," as used in these articles, is geographical and historical rather than political, and refers to the citizens of British India, a region that is today divided into India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Myanmar (Burma), and the disputed area of Kashmir.

Preface

This, along with my articles on Yukio Tani and Youssuf Ishmaelo on this site, is a chapter from the book I’m trying to put together on turn of the (nineteenth) century jujutsu and professional wrestling. I never intended to write a book, but the interest of the subject took hold, and it somehow seems that the book itself wants to be written. At any rate, when I began to write on these subjects, help and material began to flow my way from some excellent historians and researchers.

I want to acknowledge my use of material from Joseph Alter’s historical essays on Gama in the first part of this article, as they were an invaluable source for Gama’s pre-England career. [EN1] Grateful thanks also go to Robert W. Smith, who first stirred my interest in Gama with his 1963 Black Belt article, who supplied me, just at the right time, with a copy of Muzumdar’s Strong Men Over the Years, and who also allowed me to quote extensively from his Stanislaus Zbyszko letters; to wrestling historian Mark Hewitt; to Michael Murphy, who has been amazingly generous in sharing material from his collection; to John Spokes, for the loan of his old editions of Health and Strength; to Joseph Svinth for sending me copies of Ernest Sodergren’s clippings on the Great Gama (which he in turn received from Nadeem S. Haroon); and to the British Library and British Newspaper Library.

Hopefully that’s included everyone, and if anyone has further information

on Gama and the other great Indian wrestlers of the early twentieth century,

please contact the editor at jsvinth@ejmas.com.

I.

Wrestling in India has a long tradition, but its early history is obscure, and probably lost. S. Muzumdar, in his classic Strong Men over the Years (Lucknow, 1942), wrote that "The great art of Indian wrestling has its legends but no history whatsoever," and so he chose to start his account of wrestling and wrestlers in 1892, when the English champion Tom Cannon visited India and was defeated by the 21-year-old Kareem Buksh. That, it seems, was the first international contact between the Indian and western schools of professional wrestling.

The first great Indian wrestler to appear in the West was the 5 foot 9, 280 pound Gulam, who wrestled in Paris in 1900 at the time of the Great Exposition. His manager put out an open challenge and a match was made with Cour-Derelli, regarded as one of the strongest of the Turkish wrestlers then in Europe.

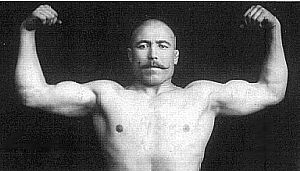

Gulam, ca. 1900

Courtesy Michael Murphy

Edmond Desbonnet’s account of the bout was given in his 1910 book, Les Rois de la Lutte:

From the beginning of the bout Gulam demonstrated a crushing superiority over the Turk Cour-Derelli. As soon as the whistle signalled that the two contestants could come to grips, the Hindu, agile and swift, sprang on his adversary and threw him with a marvellous "flying mare (tour de bras)." Both of his shoulders touched the mat but, as this match brought into play big financial interests, after interminable discussions, the throw was not admitted and the bout recommenced.

Several times the Hindu used his terrible arm roll and each time Cour-Derelli rolled on his two shoulders, but got up at once. Finally, realising that his opponent was too strong, the Turk decided to crouch down on the mat, and not budge from that position for an hour and a half. He was content only to defend himself against the attacks of Gulam, who, tired of all this, invited him to get up, and to emphasize his contempt at the incorrect attitude of his opponent, he punctuated his invitation with several kicks to the kidneys. But Cour-Derelli, who probably found it fine where he was, did not wish to get back up when the judge signalled him; Cour-Derelli seemed rooted to the mat for the whole match. Finally, the only recourse was to the points system, and, to avoid harming those [financial] interests of which we spoke above, the bets were called off. It was declared that Cour-Derelli had not been thrown, Gulam was proclaimed the winner, but all bets were reimbursed.

Be that as it may, Gulam was manifestly superior to the Turk. Although he had to wrestle the length of the bout with a sprained left arm, he wrestled a hundred percent, throwing his opponent three times.

I witnessed this memorable match with the much missed Dr. Krajewski, of St. Petersburg, and Noel le Gaulois; we occupied a box at floor level and no detail of the bout escaped us. Dr. Krajewski was enthusiastic about Gulam, who he had examined several days before when he was photographed in the pose which we reproduce here. It was in the studio of the photographer Walery that we took Gulam’s measurements.

To our mind, no current wrestler could stand five minutes against Gulam in fair wrestling, that is to say, without grovelling on the mat, a system of defense which should be banned as anti-sporting.

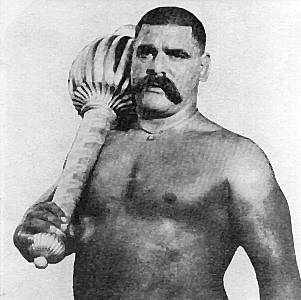

Ahmed Madrali

Gulam returned to India where, not long after (1900), he died of cholera. It was a century ago, and it’s difficult to judge his real strength from that one bout with the Turk Cour-Derelli. Historians of Indian wrestling, however, often look back to him as the greatest of their champions, and those who saw him in Paris also seemed to regard him as something special. Desbonnet referred to Gulam as one of he two "super wrestlers" of the modern era (the other was Youssouf Ishmaelo) and Stanislaus Zbyszko told Robert W. Smith that, although he had never met Ghulam himself, "I got information off one wrestler who did train with Ghulam. He was the ruler of his day, of the mat, of human strength."

***

A few years after Gulam’s death, a new prodigy came along. This was Gama (birth name, according to Robert W. Smith, Mian Ghulam Muhammad), who was born to a family of wrestlers in 1880 or so. I’ve never seen an exact birth date given for Gama, and calculations from references in books and magazines give variously 1878, 1880, or 1882. When he died in 1960 his age was given as 80, so the date of 1880 seems the most reasonable.

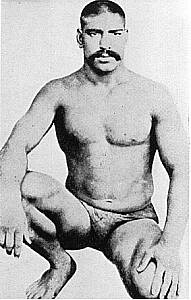

Gama, ca. 1916

His father was a top wrestler and Gama is said to have started training at age five. When Gama was eight, his father died, but training continued under the direction of his grandfather; then, when he died too, under his uncle Ida Palahwan, who vowed that Gama would become the champion his father had wanted him to be. According to Joseph Alter, "Intent on impressing upon him the desire to be a great wrestler, he constantly pointed out to the young boy that this is what his father wanted above all else." From being a child, wrestling seemed to be pretty much all that Gama knew. In time, as he reached maturity and eventually did become Champion of India, "The crown passed on to a person perhaps as great and worthy as Ghulam."

Gama first became known at the age of ten when he took part in a national physical exercise competition held by the Rajah of Jodhpur. This was not in a wrestling contest, but in an endurance competition of bethaks (free squats), the fundamental conditioning exercise of Indian wrestling. "Over four hundred wrestlers from around India had gathered in Jodhpur," wrote Joseph Alter, "and at the Rajah’s signal the competition began. As wrestlers became tired they left the field until only one hundred or so remained. As more and more retired, all eyes turned on Gama, until, after a number of hours had passed, only fifteen wrestlers were left exercising. At this point Jaswant Singh [the Rajah] ended the contest saying that the ten year old boy was clearly the winner in such a field of stalwart national champions. Later, upon being asked how many bethaks he had done, Gama replied that he could not remember, but probably several thousand. In any event he was bed-ridden for a week."

That victory didn’t necessarily show any wrestling ability, but it did demonstrate unusual qualities of physical robustness, will power and competitiveness in the young Gama. At that time he was routinely doing five hundred bethaks and five hundred dands (stretching pushups) daily, and working on pit digging – turning over the earth of the wrestling area with a pharsa (hoe). He ate a special diet concentrating on milk, almonds, and fruit: he didn’t begin eating meat until a few years later.

Gama would wrestle every day, of course, but he didn’t compete until he was fifteen. "Very quickly, however, he proved to be virtually unbeatable, and formally became a wrestler to the court of Datiya soon thereafter." As he grew older his training routine was intensified and his diet upgraded to include meat, butter, clarified butter, and yakhi, which Alter describes as a "boiled down glutinous extract of bones, joints, and tendons, which is regarded by many Muslim wrestlers as being a source of great strength, and being particularly good for the development of knees, ankles, and other joints." The amounts eaten by the Indian champions were prodigious, and Barkat Ali gives, with what truth I don’t know, the mature Gama’s daily diet as six chickens or an extract of eleven pounds of mutton mixed with a quarter pound of clarified butter, ten litres of milk, half a litre of clarified butter, a pound and a half of crushed almond paste made into a tonic drink, along with fruit juice and other ingredients to promote good digestion. This expensive high fat, high energy, high everything diet helped to drive Gama’s daily training, which in maturity consisted of grappling with forty of his fellow wrestlers in the court, five thousand bethaks, and three thousand dands.

The figures may be exaggerated, I don’t know, but no one doubted Gama’s dedication to his conditioning routine. The English writer on wrestling Percy Longhurst recalled seeing Gama training when he was in England:

The morning he spent in going through a few hundred repetitions of the ‘dip’; this was followed by several bouts (no rests between) with his fellow Indians, Imam Bux and another. A two hours rest and a meal followed. The meal, by the way, was a quart of broth, concocted of a couple of fowls, with spices. The afternoon was given up to deep knee bending. Nude but for a loin cloth, out of doors in the warm September sunshine, Gama began his up-and-down motion. Methodically, rhythmically, his open hands on the top of a post standing about 4 foot out of the ground, Gama went on with his knee bending. There was nothing hurried about it; he started as though he meant keeping on forever; and after watching him for a long while, that, so I concluded, was his intention. I timed him by the watch for twenty minutes, and still he continued. The perspiration was streaming down him, but there was never a sign of wavering or slacking off. For how long he actually did continue I do not recall. I was deep in a chat with Mr. Benjamin [Gama’s manager in England], who told me that when Gama did finish he would undergo a vigorous all over rubbing with dry mustard.

To watch him doing the dipping exercise was a revelation. There was power put into every movement, up and down… It was easy to understand, watching the regular rise and fall of the smooth brown body, the bending and straightening of the rounded limbs, to what extent not only the arms and the shoulders, but the muscles of the chest, abdomen, back and loins participated in the vigorous execution.

One could understand how Gama had acquired the enormous bulk of solid flesh at the back of his upper arms; whence came the wonderful size of the muscles around the shoulders and the base of the neck. Smooth, solid muscle; muscle in bulk; yet again I must repeat that when Gama ‘set’, for example, his arm, his fist clenched, that acute outlining of the individual muscles on which the enthusiastic physical culturist is wont to pride himself, the ‘steel bands’ and ‘hard knots’ beloved of the lady fiction writer, were conspicuous by their absence. All one saw was a rounded swelling, a smooth prominence here and there.

But there was strength, an abundance of it, in those smooth and supple limbs. Anyone who saw Gama overcome Dr. B.F. Roller could be sure of that.

Gama gained real recognition as a wrestler in 1904, apparently, when he had a series of impressive wins at a tournament organised by the Maharajah of Rewa. In 1906 he won a tournament organised by the Maharajah Pratap singh of Orchaz and was given a position of wrestler at the Maharajah’s court. Over the years he defeated the champions of other states and cities – Govalior, Bhopal, Tikamargh, Datia, Indore, Baroda, Amritsar, Lahore – and around 1909 he gained recognition as Indian champion when he defeated his famous rival Gulam Mohiuddin. Gulam Mohiuddin was regarded by some as Gama’s equal, but when they met he was defeated in only eight minutes.

Ten minutes, eight minutes, two minutes – when you read the accounts of Gama’s Indian matches, such as they are, it seems that his opponents, some of them well-known champions, were simply brushed aside. But there was one exception, the famous Rahim Sultaniwala. He was older than Gama, a one-time student of the great Gulam, and he is described as standing six foot eleven and weighing 270 to 300 pounds – exaggerated figures, I would imagine, but still much bigger than Gama, who was around five foot seven and 200 pounds.

There are some discrepancies in the accounts, but it seems that Gama and Rahim Sultaniwala met two or three times before Gama’s visit to England in 1910. According to one version of events, the two men first met at Junagarth in the state of Lahore when Gama was nineteen. Rahim took the offensive in that match and was somewhat taken back when his attacks failed to make much headway against his younger opponent. In the second half of the match the advantage probably lay with Gama, but the action was stopped after sixty minutes by the Nawab of Junagarth and a draw given. The second time the two men met was around 1909 when they wrestled to a two-hour draw.

Rama Murti, who trained Rahim Sultaniwala for his matches with Gama

S. Muzumdar gives a slightly different version of events, writing that the two men first wrestled a twenty-minute draw at Datia. (Joseph Alter dates this as late as 1907.) They met again at Indore in 1909, where the result was another draw "after a cunning fight which lasted for three hours"; and then a few months later they wrestled yet another draw at Lahore, this time in a contest of two hours ten minutes. "Gama was not to be mastered," wrote Muzumdar, "nor could he bring his great opponent under control."

Quite how Gama’s visit to England came about is not too clear, but the

driving force behind it was R.B. Benjamin, an English wrestling promoter.

According to one report, it was after seeing Gama defeat the well-known

Chandra Singh Mudaliwala that Benjamin decided to bring Gama over to England.

On his part, presumably, it was a straight commercial venture, whereas

for Gama it was a chance to test himself against Western champions and

establish himself as the greatest wrestler in the world. For others, such

as Sharat Kumar Mishra, the Bengali millionaire who sponsored the tour,

it was a way of demonstrating the strength of Indian physical culture right

in the heart of the British Empire. At any rate, in early 1910, Gama, along

with fellow wrestlers Imam Bux (his brother), Ahmed Bux, and Gamu, set

sail for London.

II.

They arrived in England in April. Some Indian writers have stated that Gama intended to take part in the John Bull wrestling tournament but was refused entry because of his relatively small size. In fact, there was no John Bull Tournament, and it’s unlikely that Gama’s size would have been any problem: the much lighter Esai Maeda (Yamato) competed successfully against heavyweights in the Alhambra Tournament, and Gama, at a little over 200 pounds, was not small by the standards of the day.

Anyway, by early May the Indians were settled in their training quarters, and Health and Strength announced "The Invasion of the Indian Wrestlers" in its May 14 issue. The members of the troupe were listed as Gama, Champion of India; Imam Bux, Champion of Lahore; Ahmed Bux, Champion of Amritsar; and Gamu, Champion of Jullundhur. Their weights ranged from about 198 to 206 pounds, and the article noted that none of the wrestlers trained with dumbbells or barbells.

They would rise at 5:30, wrestle for two hours, then drink a quart (two pints) of milk with Indian spices. Breakfast at around 11:00 would consist of eggs, dahl, and rice, prepared by their own cook, who had travelled from India with them. A rest followed and then at 3:30 there would be two hours of exercise. About 7 o’clock, the main meal of chicken or mutton would be eaten. Finally, before retiring for the night at 9:30, another quart of milk with spices: the wrestlers had brought twenty varieties of spice with them.

The magazine also carried a challenge:

The Sensation of the Wrestling World

Exclusive Engagement of India’s Catch-as-catch-can Champions.

Genuine Challengers of the Universe.

All Comers. Any Nationality. No One Barred.

GAMA, Champion undefeated wrestler of India, winner of over 200 legitimate matches.

IMAM BUX, Champion of Lahore.

AHMUD BUKSH, Champion of Amritsar.

GAMU, Champion of Jullundhur.

(These wrestlers are all British subjects.)

£5 will be presented to any competitor, no matter what nationality, whom any member of the team fails to throw in five minutes. [EN2]

Gama, the Lion of the Punjaub, will attempt to throw any three men, without any restriction as to weight, in 30 minutes, any night during this engagement, and competitors are asked to present themselves, either publicly or through the management. The Indians, according to contract, are compelled to meet all champions on the above terms. Any man proving he has been refused the right to wrestle with the Indians will be presented with Five Sovereigns by the management from the Indians’ salary. [EN3]

NO ONE BARRED!! ALL CHAMPIONS CORDIALLY INVITED!! THE BIGGER THE BETTER!!

I’m sure the Indians were eager to meet the top professionals of the time, but in issuing a genuine challenge they were, in a way, intruding into a rather cozy world of pro wrestling which operated largely as a music hall entertainment and was, as George Hackenschmidt himself explained, a "business." So if the Indians had expected to meet professionals willing to engage in genuine matches, then they were going to be disappointed, and for quite a while, no challengers came forward.

By July the lack of any response was becoming noticeable, so much so that The Sporting Life carried a short article entitled "Gama’s Hopeless Quest [to find a genuine opponent]." Around the same time Health and Strength referred to the "apathy, cowardice, call it what you will" of the current crop of professional wrestlers. And interestingly, the article also mentioned that Gama had, in fact, had many offers of "lucrative employment" if only he would be willing to "go down" – that is, take part in arranged matches. But then, the article went on, "He simply doesn’t understand what that means."

Gama’s challenges were also printed in the magazine:

GAMA TO ZBYSCO

Gama is prepared to meet Zbysco in London and throw him three times in one hour for £100 or £200 a side.

GAMA TO GOTCH

Match £250 a side.

Match to take place in London.

GAMA TO THE WORLD

Gama will wrestle any man in the world from £100 to £500 a side.

Match to take place in England.

A SENSATIONAL CHALLENGE: INDIA V. JAPAN

Gama is prepared to throw every one of the thirty Japanese wrestlers now showing at the Exhibition in one hour – actual wrestling time.

Gama will guarantee to carry out the contract, the only stipulation being that the men stand five yards apart, and as soon as the signal is given to start they approach one another and begin wrestling. Ten minutes rest to be allowed after Gama throws the first fifteen. £100 a side.

Gama is also prepared to throw the champion of the Japanese ten times in thirty minutes for £100 a side.

Well, a little later Gama’s challenge was taken up by the well-known American professional, Benjamin "Doc" Roller. Ben Roller was a character in his own right: a real medical doctor, apparently, who had gained his degree at Pennsylvania; a natural athlete who had excelled at football and heavy field events before turning to professional wrestling in 1906 at the rather late age of thirty. It’s difficult to say how skilled he really was, but Roller had worked with Frank Gotch and was a busy professional: he seemed a decent first test for Gama.

A correspondent for The Sporting Life wrote an interesting account of Gama in training for the Roller match, which is worth quoting:

He is not wrestling with one eye on his adversary and one on the spectators. He is not speculating on the effect his wrestling may have on future engagements. At the moment there is only one thing to be done: to put his man down as soon as may be.

There is no wasting of time playing for head holds or holds of any other kind. He doesn’t play for holds at all, he goes in and takes them, and should it happen that his opponent is clever enough to avoid the first attack he also has to be ready to meet the next, which comes upon him with lightning rapidity.

Quickness is perhaps the Indian champion’s quality which most impresses the onlooker. The latter is apt to overlook the tremendous force which is concentrated in the Indian’s rapid movements. Gotch is said to be quick, he has laughed at all the European wrestlers he has met because of their elephantine slowness. The cinematograph pictures of his contests with Hackenschmidt and Zbysco proved that by comparison with them he is quick. He has declared, and he has realised, that quickness is strength; that quickness in a wrestling bout is of infinitely more importance than mere physical bulk and ponderously exerted strength, -- but if ever he met Gama it will be interesting to see how he compared in this respect with his challenger. He will be up against a man who has at least equally as great an appreciation of the value of quickness as himself and possibly greater executant power.

But the strength is in Gama also. One can see it in the fine proportions of his figure, the enormously deep chest, the strong loins, the huge thighs, and the powerful rounded arms… ‘The strength of an ox and the quickness of a cat’ were the words in which one spectator summed up Gama.

He is a worker and he sees to it that his opponent needs to be a worker too unless he is to go down on his shoulders within the first five seconds. There is no letting up, no breathing time, no holding off to gather wind and strength when Gama is wrestling. Move follows move with such tremendous rapidity that it is not entirely easy to distinguish the particular chip which brings about a fall. From grip to grip he changes with the quickness of lightning, arms and legs both at work, the one ready at an instant’s notice to supplement the movement of the other.

Thus it is that one loses sight of the man’s enormous strength.

But his opponent knows it’s there. There is no violent striving for half-nelsons; there are no deliberate movements by which an opponent may be held so that a particular hold may be obtained. An uninitiated person might almost consider that he was witnessing merely a rough-and-tumble, get-hold-anywhere encounter, but it is not so. There is a purpose behind every movement. Both offensively and defensively he knows the value of leg work and in addition he knows a good deal about leg work which the smartest catch-as-catch-can wrestler in this country has never thought of.

And all the while his wrestling is clean. There is no violent exercise of his strength when having forced an adversary into a particular decision which suggests that if the victim does not move something will be broken. There are no strangles, no foot twists, no bridging or head spinning, the latter for the very simple reason that the Indian wrestler has no use at all for ground wrestling. His wrestling is done on his feet. If forced to the ground, or to ease himself he goes down, his object is not to sit there and seek defence, but to get up as quickly as he can and resume the struggle afoot, and the opponent who does try ground wrestling against Gama will very quickly find that he has made an unlucky choice. It is no part of his game to overturn a man who lies on the floor, but he can do it if necessity arise. There was a man in Scotland, and he was four stone [56 pounds] heavier than Gama, who found this out.

It is said that no opponent has ever got behind the Indian champion. One can believe it.

… One could learn something from a slight incident that occurred on the occasion when the writer saw Gama at work. A sturdy English wrestler was opposed by the least skillful of Gama’s compatriots. Within six seconds of time being called the Englishman was on his back. His opponent, admittedly somewhat heavier than himself, simply walked into him and buttocked him.

The winner was thrown by Gama inside two minutes.

***

The Alhambra was "packed to the point of suffocation," with hundreds turned away, and "the air was electric with excitement." When the men came together, it was clear that Roller was much taller than the "stocky native of the Punjab." The weights were announced as Roller 16 stone 10 pounds (234 pounds) and Gama 14 stone 4 pounds (200 pounds). When the emcee declared that "no money in the world would ever buy him [Gama] for a fixed match, there was a perfect hurricane of approving shouts."

As soon as the signal to start was given, Gama came out with his "curious kind of galloping action" and immediately dived for a leg hold that Roller only just managed to escape. The American tried to use his additional weight to stall but an outside click almost had him over again. Gama then brought Roller down beyond the edge of the mat. After the referee ordered the men back to the middle of the wrestling area, he attacked again, taking Roller’s leg and then applying "a lovely back heel" which sent Doc down to the mat with a crash. Gama immediately put on a half nelson with body roll and turned Roller over for the first fall. It had taken just 1 minute 40 seconds.

As the second bout started Roller was, understandably, much more wary and a lot of time was spent sparring for a favourable position. Roller seemed unsettled by Gama’s feinting, and then the Indian dived for the leg and Roller was down, with Gama onto him immediately. Now the rest of the bout was a struggle for the pin-fall: Roller always on the defensive and Gama always on top, often drawing favourable comment for his excellent leg work. Roller was in difficulties throughout (at one point he winced when Gama put on a powerful body hold) and although he broke free from holds several times, Gama was always quicker and would immediately apply another move. Eventually Roller, "trussed up on all sides," was turned over for the second fall after 9 minutes 10 seconds of wrestling.

Gama’s victory was greeted with "considerable enthusiasm." It was also well received by the press and some commentators thought (rather naively) that it could lead to a revival of real wrestling. Gama’s "cat-like quickness" was noted, and the reporter for Health and Strength wrote that "I shall never forget the whirlwind swiftness of that first bout; the people gasped as they looked on, and they cried with one accord, ‘There’s no swank there!’" In the same magazine, "Half Nelson" commented, "Frankly, I was astonished at the Hindoo’s performance… The moment the contest started it could be seen that Gama was full of confidence, and displaying prodigious strength, he had the mastery throughout. Not once in either fall did Roller venture upon the initiative; indeed, he had his work cut out all the time to keep his shoulders off the mat… One most important thing – he [Gama] wrestles on the ‘dead level’ all the time."

After the match it was reported that Doc Roller had suffered two fractured ribs. (Health and Strength said one broken rib on his right side.) The consensus was that the injury had occurred in the first bout when Roller had been brought down off the mat, and credit was given to him for wrestling on, showing little sign of the damage except maybe when he gasped as Gama put on a body hold. According to the reports Roller was taken to Charing Cross Hospital and attended to by Dr. Edward B. Calthrop, who diagnosed fractures of the seventh and eighth ribs on the left side. In the evening Roller was visited at his hotel by a Sporting Life reporter who found him with his body bandaged and "in excruciating pain." Roller was disappointed that the injury had handicapped him during the bout; he felt that he could have done better if he had been unhurt, but still considered Gama "a great wrestler."

At the end of the contest, while Gama was being cheered, the famous Polish wrestler Stanislaus Zbyszko came forward to shake the Indian’s hand and congratulate him on his victory. An announcement was made that Zbyszko and Gama would meet in a month’s time, September 10, at the Stadium (Shepherd’s Bush). And on behalf of Gama a challenge was issued to the world, for £1,000 upwards. Frank Gotch was specifically named, and Gotch’s agent, who happened to be present, said that Gotch would be happy to meet any wrestler who visited America.

***

But first there was another contest to be decided. On September 5, a Monday afternoon, Imam Bux was meeting the well-known Swiss professional wrestler John Lemm at the Alhambra Theatre. The match was for £100 a side and a share of gate receipts, catch-as-catch-can style, the best of three falls.

Imam Bux

Imam Bux was the second string of the five-man troupe, although some observers thought that he might actually be a better wrestler than Gama himself. John Lemm was a leading professional who had won the Alhambra and Hengler’s tournaments and who for the past couple of years had been trying to get a match with Hackenschmidt or Gotch. In 1908, when the ill-fated Professional Wrestling Board of Control selected four men to wrestle for the Championship, John Lemm was one of the four (along with Gotch, Hackenschmidt, and Zbyszko). Lemm was short for a heavyweight, about five foot seven, but he weighed 200 pounds and was quick and strong, being known for a determined, rushing style. He was very powerfully built, particularly in the legs, and I think he may have claimed a world record performance in the squat at one time.

Once again the Alhambra was packed for the contest. As the two men stepped on the mat they presented a contrast in physique: Lemm short and heavily muscled, Imam Bux six foot tall, rather gangly and loose limbed. The weights were announced as Lemm 14 stone (196 pounds), Imam Bux 14 stone 8 pounds (204 pounds).

At the signal to start Lemm rushed out in his usual style and seized Imam Bux in a waist hold. After a brief struggle he used a back heel and Imam Bux went down flat on his back. Recovering immediately, he escaped any follow up, and from that point on, Lemm was never in it. Soon after, Imam Bux lifted Lemm up "easily" and threw him to the ground, following up immediately and putting on a half nelson and crotch hold. He turned Lemm over and despite his struggles, the Swiss was pinned in 3 minutes 1 second. "It was a masterly piece of work," said The Sportsman.

John Lemm

After a ten-minute rest, the second bout started and "Once more the Indian astonished his rival by his tremendous quickness." Imam Bux went for the legs and both men went down, interlocked. They struggled and there was an awkward moment for Imam as Lemm caught his leg, but he escaped and then Lemm was underneath – and again he was fixed in a half nelson, as Imam Bux applied his full weight. Lemm seemed to use every ounce of his strength in trying to resist, rocking from shoulder to shoulder to avoid the pin, but he was forced down and the referee awarded the fall in the very short time of 1 minute 8 seconds.

Imam Bux’s victory over Lemm in a little over four minutes of wrestling was a sensation. Lemm himself was crestfallen, but shook Imam’s hand and congratulated him. The press was full of praise for the Indian, saying that "with such pertinacity did Bux pursue his course that he made Lemm – the hero of so many protracted battles – look quite commonplace." Imam Bux was "really like a great cat, wonderfully nimble and lissom, able to turn and twist with lightning-like dexterity," and overall it was a "marvellous performance."

A fulsome summing up was given in Health and Strength, the writer stating that the match was "one mighty thrill from start to finish."

During that five minutes I saw more actual wrestling, more variety of holds and locks and throws, more dramatic, soul-stirring incidents than I have witnessed for many a year.

Let us have a few more big matches like unto that, and I tell you straight that the grappling game will soon become the greatest game of all.

To be continued.

ENDNOTES

EN1. Publications by Professor Alter consulted included "Gama the Great: Indian Nationalism and the World Wrestling Championships of 1910 and 1928," Yugantar Punjab, Summer 2000, http://www.yugantar.com/sum00/gama.html; "Gama the World Champion: Wrestling and Physical Culture in Colonial India," Iron Game History, October 1995, http://www.aafla.com/search/search_frmst.htm, then use "Gama" as the keyword; and The Wrestler’s Body: Identity and Ideology in North India (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1992); http://www-ucpress.berkeley.edu:3030/dynaweb/public/books/south_asia/alter.

EN2. Depending on exchange rates and how you calculate purchasing power, in 2002 it required about £58 to equal the purchasing power of a pre-WWI pound sterling. Thus £5 represented a significant amount of money for an English working man, and a fortune for an Indian labourer.

EN3. A sovereign was a gold coin valued at 20 shillings

(e.g., £5). The modern numismatic value of a 1910 sovereign in very

fine condition is on the order of £60.