Journal of Theatrical

Combatives Sept 2005

Maggie in me - Million Dollar Baby and the meaning of martial arts

practice

Deborah Klens-Bigman, Ph.D.

On the plane going to Tokyo this summer, trapped by a 13-hour flight, I

was intrigued to see that JAL featured Clint Eastwood’s Million Dollar

Baby as part of its in-flight entertainment. I had wanted to see

it, but, as usual, had not managed to make the time. I knew about

the end-of-life controversy in the story, knew about Hillary Swank's

training regimen. Moreover the coincidence of the Terry Shaivo

case coming about and reaching crisis level in the US after the movie's

release provided it with (forgive me) a priceless, if unexpected,

publicity boost. Pundits and advocates for the disabled made

arguments; Eastwood and his cast wisely kept mum. So much had

been written and said about the film, it was almost (I thought) as

though I had already seen it, when I had not.

I should point out that I am something of an Eastwood fan. Not so

much of the guy himself in a way, but the movies. Once considered

schlock, films like The Good, The Bad and The Ugly are now considered

classics of a film genre, the Western, that is all but dead.

While I never felt much interest in Eastwood's acting ability, I have

enjoyed watching his face age from the homoerotic attractiveness of the

TV series Rawhide to the weather beaten elegance of Pale Rider.

So, I wanted to see the Million Dollar Baby, but in some ways felt it

was almost beside the point. However, there I was with 13 hours

and not much to do, so what the hell. Might was well go to the

movies.

I don't know many women who like boxing or wrestling, but I actually

do. When I was in junior high, I went to wrestling matches

(Greco-Roman style, not professional style) by myself because I could

not get anyone to go with me. I enjoyed watching each wrestler as

he left his teammates on the bench and went forth alone to meet his

adversary. Once he was out on the mat, no one could tell him what

to do. He would win or lose by himself.

I probably would have gone to boxing matches if there were any, but

there weren't (and I somehow think my parents would have drawn the line

there, anyway). I had to content myself with televised

matches. I remember sitting with my uncle watching Muhammad Ali

in the'70's, while everyone else either left the room or

complained.

My interest in boxing held true at least until something like maturity

took over. The inherent violence in people trying to destroy each

other’s faces, albeit under certain rules, has started to bother

me. I now think people should wear head protection.

Muhammad Ali has Parkinson's. Another uncle of mine (not the

boxing fan) died of Parkinson's. There you are.

Some comment has been made of the brutality of the boxing scenes in the

Million Dollar Baby. Most video I've seen of women's boxing has

the opponents wearing head protection. Eastwood has his fighters

duking it out without it, which is a little startling. In a way,

though, it's like taking off the training wheels. The opponents

are consenting adults who seem to have their brains more or less intact

(at least to begin with).

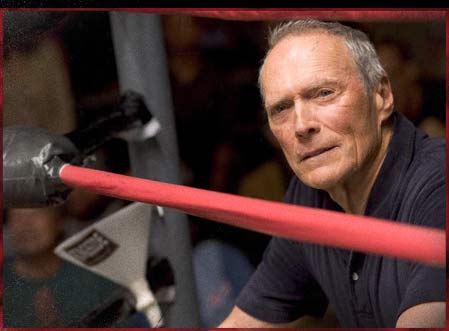

The film opens with Eastwood's character, Frankie Dunn, a trainer and

sometime manager, holding back a fighter from a championship

bout. Frustrated, the boxer changes to a different manager and

gets, and wins, the title bout. That's how stuff goes for

Frankie. He's his own worst enemy when it comes to success.

His friend, employee and conscience, Eddie "Scrap Iron" DuPris (Morgan

Freeman) seems to have more business savvy (why his job consists of

cleaning toilets is never really explained).

In these scenes, Eastwood's Frankie is a hard-bitten type. The

sometimes stark lighting shows every well-earned crag on his on his

aging face.

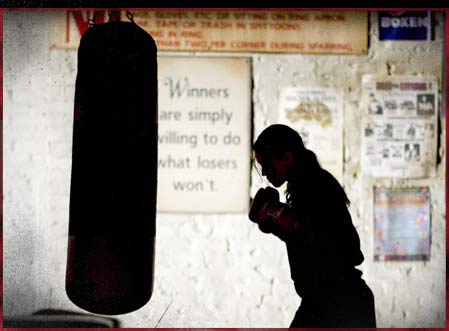

Enter Maggie Fitzgerald, a product of a white trash background who

moves to the big city. She works as a waitress but is so bad at

it she has to swipe food off customers' plates to make up for her lack

of tips. She finds Frankie's gym and trains late into the night,

even though Frankie ignores her, stressing to everyone who will listen

that "I don't train girls," and that her age, at 30, makes her too old

to be a contender.

The other boxers make fun of her, along with a stringy kid with a big

heart, a big mouth and no talent whatsoever. Throughout the film,

Eastwood contrasts these characters with each other. More than

just comic relief, this character, alternately nicknamed "Danger" or

"Flipper" depending on who is speaking, offers a contrast to how men

view a "lovable loser" type with a woman in a male-dominated

sport. At first, their treatment is nearly identical. After

Maggie gets through a few rounds of verbal sparring, however, they

simply ignore her.

Maggie has no reason to keep going. The other boxers threaten

her, Frankie ignores her. Only Scrap, who lives at the gym and

sees her training into the night, begins to see her potential and gives

her a few pointers, more than enough to keep her going.

We pretty much know the rest of the story. Maggie becomes

successful by knocking out one opponent after another. Despite

Frankie's entreaties that she develop some strategies that would

prolong fights and make her more marketable, she continues to do it her

way, earning fans by developing an Irish persona based on Frankie's

study of Gaelic and her own stubborn character.

Maggie's success does not sit well with her po' white family,

however. She buys a house for her mother with cash, only to be

told by the ingrate that her welfare benefits would be cut if she

accepted it. Cranking up the mortification, Maggie's mother

further tells her that people think what she is doing, making a living

as a boxer, is odd and freakish. Sophisticates may laugh at the

rube portrayal, but I grew up in Appalachia (enough said). It is

a brutal characterization in what is, sometimes, a brutal film.

Maggie finally makes it to her title shot. Her opponent is "Blue

Bear," a former East German prostitute who bends and breaks the rules,

but, as Freeman's narration notes, "the crowds loved her." Though

I can see the need for this character to provide the impetus for the

tragic ending of Eastwood's vision, it is hard to justify what happens

next. Perhaps after holding back another potential champion,

Frankie is determined not to make the same mistake again. Fine,

but why is Maggie so woefully unprepared for this particular opponent,

especially after seeing a video tape and no doubt knowing her

reputation? Though the climactic battle is exciting, it is, in

retrospect, a weak point in the film.

When Maggie suffers a traumatic spinal injury as a result of Blue

Bear's treachery in the ring, the ending of the film is somewhat

inevitable, even though Eastwood devotes about 1/2 hour to it.

Maggie's family crawls out from under their rock to visit her at the

rehab center. After spending a few days as tourists, they finally

show up in order to get her to sign over her assets to them.

Finally, Maggie finds her spine (though it is injured) and refuses

their request. Bedridden as she is, she has enough force of

personality to back them off and make them leave her alone.

Maggie's ordeal wears down Frankie. (It seems to wear down Swank,

too. Her physical transition from buff fighter to rail-thin

invalid is shockingly, and cleverly, revealed). This is the best

part of Eastwood's performance. The craggy, determined face

literally sinks during the last half hour of the film. It is

almost like the end of the film becomes a duel between Swank's brutally

honest performance and That Face.

Most of us know the film's ending (especially since the video came out

recently), so I won't elaborate, since it is not part of my larger

argument, which is coming soon, I promise.

So, here we have a film that in many ways could be said to be rank with

cliché. The scrappy "girl" and the cratered veteran, the

wise old black dude and the hapless kid. They ignore her.

She wins them over. She becomes too successful for her own

good.

The day after I arrived in Japan, I managed to drag myself to the dojo

where I train in Tokyo. I suffer pretty badly from jetlag,

especially on the first day, and, until I actually showed up there, I

wasn't sure I was going at all (I even got lost on the way to the

station, a trip I've made many times). I didn't even bring my

keikogi, figuring I'd just show my face and then wander off somewhere,

still trying to adapt to the day and time shift. No way. My

teacher looked me over, and when he found out my gi was still packed in

my luggage, said, "Here, wear one of mine." So, comically

outfitted in a gi and hakama that were too large for me, I proceeded to

have my butt kicked for two hours.

It was the rainy season, but the dojo air conditioning was not

on. Pretty soon I was soaking my borrowed duds, my scent mixing

with my teacher's. He kept correcting, correcting and I kept

working, working. Do it again. No, again. No again,

again.

Then it hit me, how much my story in martial arts is like Maggie

Fitzgerald's story in Million Dollar Baby, though, hopefully, with a

better outcome.

When I started at the dojo, almost 20 years ago, the reaction of my

sempai (all guys) was a mixture of curiosity and a sense of

something not being quite right. I think there is a sense of

skepticism in iaido dojo about new students anyway. People are

reluctant to accept newcomers because they often don't stick

around. More true for women who face, I think, more opposition

generally when they take up a martial art, and have seemingly many more

demands on their free time, whether by choice or otherwise.

So, my new-found colleagues, when they took me out for a beer my first

week, were nonplussed when my answer to their question as to why I was

there was that it was my 30th birthday present to myself.

As time wore on, I was ignored and shunned from time to time.

Parties and events took place without me hearing about them until

afterward. One guy told me flatly that "women don't traditionally

study long sword." After four months I was ready to quit, to find

something more welcoming, or easier to get into, or to simply go back

to the fencing salle I came from. But I didn't.

I didn't quit for a number of reasons, but the most important one was

that I had a mentor, like Maggie. The instructor at the time

refused to give up on me; in fact, he pushed me to be better, told me I

had to be better than the guys. He pushed and corrected and

advised. As a black guy, I think he sympathized with the fact

that I was not readily accepted, realized my determination, and kept

hooking my desire to do better. It was not that he recognized my

potential as a martial artist; to this day stubbornness is my best

asset when it comes to this stuff. I consider myself – like

Maggie – to have minimal talent. I just practice a lot – as much

as my schedule will allow.

The other reason I did not quit was Otani Sensei. At that point,

he only came in to the dojo once or twice a month, but he always had a

kind word. I found out later that Sensei had three daughters, but

no sons. He also saw no reason I could not do well, and he told

me so every time I saw him.

Since they didn't give up, I didn't give up. Eventually, I

endured everything, including a period of a year or so after my

instructor-mentor left and no one would teach me anything new. I

learned to correct myself, and teach myself. To annoy people by

asking questions, and to push into the areas of the style that I didn’t

fully understand in order to learn them better.

At the end of the Million Dollar Baby, Frankie berates himself for

Maggie's fate. Scrap tells him that people go through their whole

lives without ever getting a shot at a title. In spite of the sad

outcome, Frankie had allowed Maggie to "take her shot."

We have had a small trickle of women who have come through our dojo in

the 19-plus years I have been there. One has now stayed for a

short time, while the rest have come and gone. While I am

comfortable being in the instructor’s role, I am not comfortable being

a mentor; I know from watching some of the senior students and Otani

Sensei that mentoring has its downside of disappointment.

Sometimes the chosen student does not want to live up to the

expectations of the mentor; sometimes the mentor's demands are too

steep, and sometimes the student is honestly not worthy of the

attention. The best I can do as an instructor is guarantee that

people who come to our dojo get their shot if they work for it.

At least they can all get that.

Million Dollar Baby, 2004 Warner Bros. Pictures, Directed by Clint

Eastwood. Available from Warner Home video, Burbank, CA, USA.

Photos courtesy Warner Brothers.

Our

Sponsor, SDKsupplies