From Sandow’s Magazine 43:18 (January 1902), 28-31. Contributed by Robert Reinberger.

"What is Bartitsu?" asked the Person-who-draws-the-pictures, as we walked down Regent Street.

"Bartitsu and Jujitsu," I began, with a refined Japanese accent.

"Caught a chill?" enquired the person.

"No; why?"

"Thought you were sneezing," said he. "Go on."

But truth to tell I could not go far; for it was with the intention of learning, so to please the Fates and Mr. Barton-Wright, that I recently attended the Tournament which was recently promoted by the latter, and held at the St. James’s Hall on December 11th last, with a view to placing before the public a scientific exposition of his much-discussed system of self-defence – Bartitsu.

It cannot be said that the conduct of the Tournament was a matter for congratulation to those concerned in its organisation. And, to anticipate for the moment, though a good evening’s sport was eventually obtained, we did not learn much about Bartitsu. The hall is large and was fairly well filled, particularly as regards the unreserved seats, where a lusty and expectant throng filled every available corner.

Everything comes to him who waits. The audience did that. Further, they indulged in occasional catcalls, frequent references to the statement on the programme that the tournament would begin at 9 p.m. punctually, and instructive comments upon the personality of fresh comers among the spectators. Also, they whistled.

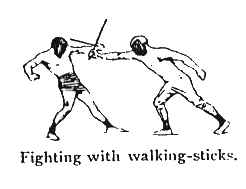

"The first item of the programme, ladies and gentlemen, will be the third." This was the announcement eventually made from the platform by Mr. Barton-Wright, whom we had never suspected previously of Irish tendencies. Elucidated, the remark meant that the third event on the printed programme – a display and bout between Instructor Pierre Vigny, world’s champion, and Mr. Noel, both of the Bartitsu School of Arms, illustrating the Bartitsu methods of self-defence with a walking-stick – would be taken first.

Enter, then, M. Vigny, tall, well set up, and muscular, walking-stick in hand, to give a preliminary demonstration of the various cuts and parries used in walking-stick play. It is difficult to describe his entertaining performance. The Person-who-draws-the-pictures opined it was an Irish jig (with shillelagh). The man behind me was firm in the belief that it was a demonstration of a new method of signalling, and that the demonstrator had been sent on to the stage to "make the best terms he could with the Boers." The gentleman in front of me came to the conclusion it was a life-like imitation of Sousa conducting his band. At any rate, it was quite nice and pretty to watch.

The bout between M. Vigny and his pupil, Mr. Noel, was more instructive. A display of veritable fencing pyrotechnics, it served admirably to illustrate the variety and rapidity of execution which marks the game. On the same principles, broadly speaking, as single-stick play, there is this important difference: both hands can be used to grasp the stick (like a quarter staff) for a parry, while the weapon, in offence, can be shifted from hand to hand with lightning speed. Rapidity and variety of motion are the two main features of the play; and it is evident that in practised hands – practised to an almost fanciful extent – a walking-stick may be made a very pretty and useful implement of both offence and defence.

Next on the programme came a display of Bartitsu wrestling methods, by Mr. Barton-Wright’s two Japanese exponents of the art, Uyenishi and Tani. The latter have been performing in public so recently in London that many readers of Sandow’s Magazine will be familiar with their peculiar style, which should be regarded, be it noted, not so much as a form of sport, as a means of self-defence. Very picturesque figures the Japs made as they walked on to the stage, their slight but well-knit frames robed in loose and baggy native costume, Uyenishi with a "vaccination mark" between his shoulders, as a neighbour of mine in the audience saw fit to describe the peculiar red Japanese symbol embroidered on his tunic.

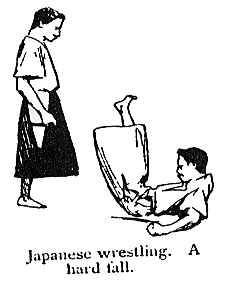

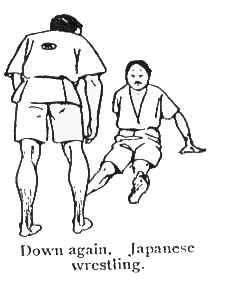

The performance commenced with an exhibition of the various falls practised under Bartitsu rules, which, briefly allow you to dispose of your opponent in the most summary and convenient manner. The display was ingenious, certainly, but in the absence of any real contest failed to carry conviction. The main impression conveyed was that Bartitsu is a capital means of warding off an expected attack: given the hypothesis of an opponent rushing in with a fair warning of his hostile intentions, and a proficiency in Bartitsu methods – not easily mastered, we should say – will probably enable you to lay your hooligan on his back with a suddenness and vehemence that will surprise him. Especially was this the case with the illustration of methods to be employed when murderously attacked with a knife by a companion. Granted suspicion of the intentions of a man by whose side you may be walking, and a knowledge of Bartitsu will stand you in good stead; but nothing will save you from the ruffian who unexpectedly draws a dagger and jabs it into your back or ribs.

An interesting item in the performance of the Japs was the demonstration of what can be done in the way of strengthening the neck against possible attempts at strangling and garrotting. A Jap was laid full length upon his back, his head resting on the mats. Across his neck a long ash-pole was laid, and upon the ends of this – two on each side – four of the heaviest men were invited to exert the utmost pressure of which they were capable. The pole was, of course, pliant, but that notwithstanding, the feat was an extraordinary one; rendered not the less so by the clever way in which the Jap wriggled himself free from the pole, while the latter was still under the heavy pressure of the four strangers. The performance concluded with a brief wrestling bout – curtailed in view of the promised match between Uyenishi and the Cornish and Devonshire Professional Heavyweight Champion, which we were destined not to see – between the pair, one lying on his back and protecting himself from attack with his feet. This was an exceptionally clever exhibition, the recumbent man resembling nothing so much, in his methods, as a fighting owl at bay. All efforts of his opponent to rush in were foiled, the climax being reached when the prostate combatant administered a neat coup de grâce with his feet that jerked the other’s legs from under him and brought him to the mats with a sounding thwack upon his back. How far the contest could be considered a serious one it is impossible to say, but the effect was good.

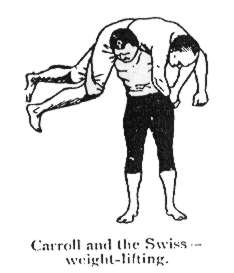

The retirement of the Japs brought on the chief event set down for decision. This had nothing to do with Bartitsu, but was a wrestling match for £50 between A. Cherpillod, Swiss Champion of the Continent, and Joe Carroll, Professional Champion of England, under catch-as-catch-can Rules. And it was in connection with this event that there occurred the unseemly bickering and wrangling which marred the otherwise sportsmanlike conduct of the tournament.

It was speedily apparent, from the delay in commencing the match, that difficulties had arisen. Then a confused explanation was forthcoming. It seems that the Sporting Life, as holding the stakes, was to appoint the referee. Up to the day of the match Mr. Barton-Wright had had no intimation as to who was to fill this position. At the last moment – at the eleventh hour – comes a telegram, signed Sporting Life, but with no name as a guarantee of authority, appointing Mr. Ferdinand Gruhn. Now, between Mr. Gruhn and Mr. Barton-Wright there is – well, a difference of opinion. Hence the latter’s unconcealed annoyance and disgust. Confusion reigned supreme, every suggestion or proposal being rejected for one reason or another. Finally, after much heated wrangling, interspersed with brief addresses to the audience from everyone who was – or conceived himself to be – concerned in the affair, and some unnecessarily vehement remarks from Mr. Barton-Wright, in which he assured us that he was a straight man, and that we knew it, it was decided that Mr. Tom Burrows, the [Indian] club-swinger should act as referee, burly Tom Cannon grimly remarking that if he were not satisfied with the judging, he should lodge an objection with the stakeholder. This by no means ended the ill-feeling displayed, Carroll’s "friends" – one in particular – continuing to be stupidly and officiously obstreperous; but already enough has been said, perhaps, upon an unfortunate contretemps, which would have been more pardonable had it not wasted so much time as to necessitate the omission of two important items in the advertised programme.

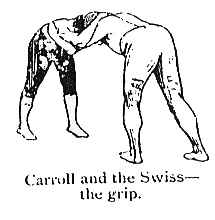

The match, as a trial between two different schools of wrestling, had an exceptional interest. The Swiss style, of which Cherpillod is so fine an exponent, aims at throwing an opponent without either falling or resorting to ground tactics. The last contest of a comparable nature in London was held as long ago as 1870, when the Cumbrian champions, Jameson and Wright, met the Frenchmen, Le Boeuf and Dubois, at the Agricultural Hall.

The bout was, from the start, a battle of giants. Both men were in fine fettle, though the Swiss was, perhaps, in better condition. Neither man took any risks, and the wrestling was of a steady nature, and occasionally monotonous. Several times Carroll found himself in a tight place, but his defensive abilities and general slipperiness stood him in good stead. More than once the Swiss swung his opponent up, but was unable to throw him with both shoulders down. At one moment both men came down, and a heated discussion took place as to whether the wrestling was for a pin fall or a flying fall (though it had been announced most plainly that the fall must, to count, be of the former description). As the pair had fallen "off the mat," no fall was allowed.

At length the protracted struggle came to an end. Cherpillod’s superior condition served him well, and lifting Carroll clean off the stage by the middle and one thigh, he gained a fair backfall in 1 hour 20 minutes.

Cherpillod was ready to go on with scarcely a breathing space, but Carroll’s party insisted on the statutory 15 minutes rest. When the pair faced each other for the second bout, it was easy to see that victory for the Swiss was only a matter of time. Carroll had suffered considerably from his previous exertions, and evidently realised this. He acted merely on the defensive, the active aggression all coming from Cherpillod.

Less than half-an-hour’s wrestling brought the end, and the Swiss champion

achieved a most deserved and creditable victory, which Carroll was the

first to gracefully acknowledge.