Originally published in The Idler, 2 (London: October, 1892), 281-286. George Brown Burgin (1856-1944) was a co-editor of The Idler, along with Robert Barr and Jerome K. Jerome.

ROUGHLY speaking, Ju-Jitsu may be defined as the art of fighting without weapons, or, sometimes, with small weapons, which was much practised by the Samurai (the aristocratic classes), and less generally by the common people, in the time of the Tokugawas. There are various methods of gaining victory by Ju-Jitsu, such as throwing heavily to the ground; choking up the throat; holding down on the ground or pushing to the wall in such a way that an adversary cannot rise up or move freely; twisting or bending arms, legs, or fingers, so that "an opponent cannot bear the pain," &c.

Atemi is the art of striking or kicking some parts of the body in order to kill or injure opponents. Kuatsu, which means to resuscitate, is the art of resuscitating those who have apparently died through violence. The most important principle in throwing your opponent was to disturb his centre of gravity, and then pull or push in such a way that he could not stand. A series of rules was taught respecting the different motions of the feet, arms, hands, the thigh, and back, which were necessary in order to do this. "Choking up" the throat was done with the hands, forearms, or by "twisting the collar of your opponent's coat round his throat." For holding down or pushing, any part of the body might be employed. For twisting and bending, the arms, hands, fingers, and legs were used.

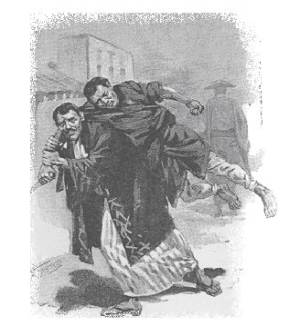

"CHOKING

UP THE THROAT."

"CHOKING

UP THE THROAT."

The art of resuscitation was considered a secret, and all pupils had to take a solemn oath not to reveal it. The simplest method of resuscitating a man who had been choked was to embrace the patient from the back, and, placing those edges of the palms of both hands which are opposite the thumb to the lower part of the abdomen, to push it up towards the operator's own body with those edges.

Another plan was to place the patient on the ground and push up the abdomen. The other kinds of Kuatsu, such as recovering those who had been killed by falling from great heights, strangled, or drowned, &c., were more complicated. It was apparently easier to choke than to resuscitate.

In the remote feudal times of Japan, Ju-Jitsu was one of the military exercises by which the Samurai kept themselves "fit" for the acquisition of anything to which they took a fancy. Since the abolition of the Feudal System, however, the art fell into disuse, but has again, within the last forty years, become popular in Japan among all classes as a method of physical training. Of course, there are many and various schools which teach Ju-Jitsu; but the differences between them are scarcely worth going into. Generally speaking, the principles of the art are:

2. —Not to lose one's presence of mind.

3. —To keep one's temper.

4. —To study the rules of respiration.

"NOT

TO LOSE ONE'S PRESENCE OF MIND."

"NOT

TO LOSE ONE'S PRESENCE OF MIND."This code goes back as far as the year 1560. Later on, a master of this interesting art arose in the person of Miura Yoshin, who, says the quaint chronicle, believing that many diseases arose from not using mind and body together, invented some fresh theories of Ju-Jitsu. Together with his medical pupils, he found out twenty-one ways of seizing an opponent, and afterwards originated fifty-one additional methods of doing so.

There was also another disinterested worthy named Akiyama, who went over to China to study medicine, and there discovered the art called Hakuda, which consisted in kicking and striking a man with fatal effect. To counterbalance this, the learned Akiyama found out twenty-eight ways of recovering persons from apparent death. His pupils, however, complained of the monotony of only twenty-eight methods of resuscitating people, and left him in disgust. Akiyama, therefore, "feeling much grieved on this account," journeyed to Tenjin and discovered 303 different methods of the art.

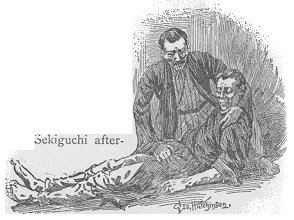

"RESUSCITATING

A DEAD MAN.''

"RESUSCITATING

A DEAD MAN.''

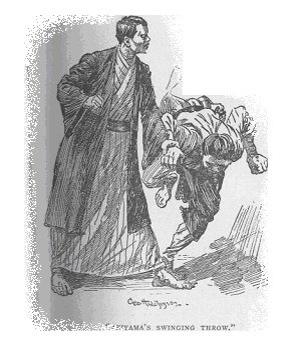

It grew to be a truism in Japan that if Akiyama felt annoyed about anything, he promptly invented more methods of scientifically putting people out of the way. This idiosyncrasy was well known to his friends, who, whenever things became a little dull, were accustomed to make slighting remarks on Akiyama's inefficiency as a "death-dealer." Whereupon, Akiyama would retire to some remote region of Japan, and there elaborate further artistic conceptions, such as the swinging throw, for relieving people from the burden of their days. He was always careful to explain that he bore no ill-will to the persons on whom he operated. The matter was purely professional and in the interests of art.

But his methods were suddenly destined to undergo a complete revolution. One day, during a snowstorm, he observed a willow tree whose branches were covered with snow. Unlike a pine tree, which stood defiantly erect and broke before the storm, the willow yielded to the weight of snow on its branches, but did not break under it. So Akiyama named his school Yoshin-ryu, the spirit of the willow-tree school.

"AKIYAMA’S

SWINGING THROW"

"AKIYAMA’S

SWINGING THROW"

Many stories are told of the skill of professors of Ju-Jitsu. One day, Sekiguchi Jushin was crossing a bridge in his master's courtyard. His lord, in order to test his skill, gradually pushed him nearer and nearer the edge of the bridge until, just as he was about to overbalance, Sekiguchi, slipping round, turned to the other side and caught his master, who, losing his balance, nearly fell into the water. Seizing hold of the prince, Sekiguchi said, "You ought to take care, and not behave like a child." At which stern rebuke "the prince felt very much ashamed, and blushed violently." Sekiguchi afterwards showed the prince that when he caught hold of him he (Sekiguchi) had stuck his kozuka (a small knife) through the prince's sleeve just to prove that he could have stabbed him if necessary.

Tereda Goemon was another noted man in his day. The attendants of a certain prince once ordered Tereda to kneel in the dust until the procession passed. He refused to do this, whereupon five or six attempted to throw him down, but he dashed them to the ground. Many other retainers then came about Tereda, crying, "Kill, kill"; but he threw them all down, seized their jittei (short iron rods), and ran over to the prince, saying, "I am a Samurai of high rank, and it is contrary to the dignity of my prince that I should kneel down before so insignificant a princeling as your honourable self. I'm sorry that I had to overthrow your men, but it was necessary to do it in order to preserve my own dignity. Here are the jittei, which I return to you."

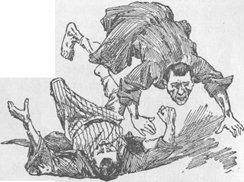

One day, Inugami Gunbei, a celebrated teacher of the Kyu Shin school, met Onogawa Kisaburo, the most famous wrestler of the time, in a teahouse. They drank sake together, and Onogawa began to brag, whereupon Inugami said that even a great wrestler might not be able to defeat an old man like himself. The angry wrestler proposed a trial of strength.

Onogawa took hold of Inugami, saying, "Can you escape?" "Of course,

if you do not hold me more tightly." Then Onogawa grasped him more firmly,

and repeated his question. He did this three times, and when Inugami said,

"Can you do no more?" Onogawa, relaxing his grip to take a firmer hold,

was in a moment pitched over "upon his honourable back" by Inugami. This

he did twice. Onogawa was "so much surprised" that he became Inugami's

pupil. Inugami also taught Onogawa how to overcome an enemy by falling

down and tripping him up.

"TRIPPING HIM UP."

Another story is told, about the time of the last Revolution, of an old Ju-Jitsu teacher in Tokio. A rumour reached him that a man appeared every night in a suburban road and mischievously but ingeniously threw down every passerby. Making up his mind to chastise this fellow, the old teacher disguised himself and went out one night to the place. Suddenly, he was seized by a man from behind and nearly thrown down. In a moment he sank his body, got rid of the enemy's arms, and struck the pit of the man's stomach with his elbow. Seeing his enemy fall, he returned quietly home, and left the apparently dead body in the roadway.

Next morning a pupil came to his presence, and, with much sorrow and repentance, said, "I used to attack passersby every night in a suburb to test my own ability, and just to keep my hand in. Last night, I was there as usual. Seeing a tottering old man come towards me, I seized him from behind and tried to throw him, but he struck me in the pit of the stomach, and the world grew dim to me with the darkness of death. After some time I recovered my senses, rubbed the bitterness out of my stomach, and came home in safety." Without revealing his identity, the old teacher solemnly rebuked the frolicsome pupil, and ordered him not to molest people in future.

The modern school of Ju-Jitsu is now known as the Kodokan Judo. The word "Judo" is really no novelty, and means the doctrine of culture by the principle of yielding or pliancy. The Kano school adopts this word in preference to "Ju-Jitsu," for it is not only a physical training, but a moral and intellectual one, the old form, Ju-Jitsu, being solely studied for fighting purposes. The modern Judo gives a theoretical explanation of the doctrine, at the same time not omitting the practical part.

In the Kano-Ryu, the whole course is divided into two parts— the grades and the under-grades. The ten grades graduate according to the degree of training, while the under-grades are divided into A, B, and C. Freshmen enter the C class of the under-grades and work their way up to B and A, whence they are admitted into the first grade. They go on to the sixth grade, which is the last step of the practical training. The higher grades above the sixth are for mental culture. No man has yet attained the tenth grade, which requires ten years of the most arduous application. Everyone is taught gratis, but all students take an oath to obey the rules. The police of Tokio are also compulsorily trained in this system.

"DISARMING WITH THE FOOT."

"Judo" aims at physical, moral, and intellectual training. "It tends to train young people in the habits and state conducive to the accomplishment of great things and objects. It fosters respect and kindness; fidelity and sincerity are the essential points which Judo students should particularly observe. We come by daily training to know that irritability is one of the weakest points we have to try to avoid in our life, as it facilitates our opponents to avail themselves."

* I am greatly indebted to Mr. T. Shidachi, LL. B., of Tokio, who very kindly placed many interesting records at my disposal for the purposes of the above article.