Originally appeared in Rolling Stone, March 24, 1988, pp. 135-140. Copyright © Robert Farris Thompson, 1988. Reprinted courtesy Robert Farris Thompson. All rights reserved.

New York City, Eighth Avenue at Forty-fifth Street, winter 1987. A young businessman and student of capoeira, the Afro-Brazilian martial art, is standing in line at a phone booth, holding a bag with a soda and a sandwich inside and carrying his berimbau, the sacred one-string musical instrument of capoeira. Four people, two phones – the perfect setting for a New York rude scene. When the athlete-businessman gets his turn, another man pushes in and places a mitt over the receiver. "No, this is my phone, you understand?" he says, knocking the young businessman’s bag out of his hand. Then the bully goes for the berimbau. Forget the salami on rye. Touching the berimbau is a very serious mistake. Within a millisecond, the capoeira student unleashes a galopante, a blow to the ear with a cupped, iron-hard hand. The unsuspecting recipient collapses on the sidewalk, moaning, "Have your fucking phone."

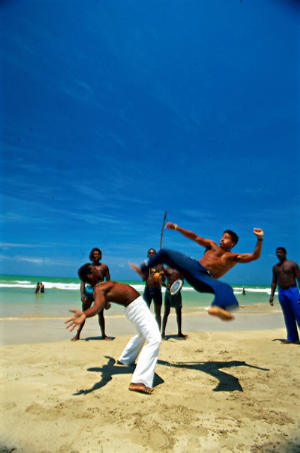

This real-life New York episode signals the arrival of capoeira (pronounced "cop-o-er-rah"). The rap revolution drilled the rhymes of black America into the national consciousness, and Bruce Lee and his comrades in arms established the Asian arts of self-defense as a lucrative leisure-time enterprise. But now it’s up against the wall, Karate Kid. Capoeira’s triple-threat fusion of Afro-Brazilian music, dance, and martial art is spreading from New York City to Seattle, winning converts in urban studios and making its mark on the airwaves and movie screens.

That’s right. An art of self-defense cum cultural phenomenon. You can hear its influence on the radio and in the dance clubs; mainstream Anglo pop and jazz are percolating with borrowed Afro-Brazilian rhythms. The emergence of capoeira has best been charted on film by Warrington Hudlin in his 1980 documentary Capoeira of Brazil, but it’s also cropping up in commercial cinema. In last year’s box-office hit Lethal Weapon, actor Mel Gibson incorporated at least one strategic capoeira move to undo his enemy, and in the forthcoming Brooke Shields vehicle Brenda Starr, the good guys are played by several of the top capoeira athletes in the United States. One of them, Jelon Vieira, is huddling with Hollywood types who want to cash in on capoeira’s popularity with a "capoeira comedy." At the 1987 Spoleto Festival U.S.A. in Charleston, South Carolina, the capoeiristas stole the thunder from their dance competition. Julinda Lewis even went so far as to say in Dance magazine that capoeira’s "speed-of-light movements" make the most brilliant break dancers look inept.

Strong words, indeed. But the real competition isn’t with break dancers, who share capoeira’s African roots. The rivals are Asian martial artists. Practitioners of both disciplines on the West Coast claim they strive for a professional symbiosis, sometimes using the same training halls, merging their moves and avoiding confrontation. "I would never compete [against the other martial arts]," said Bira Almeida, a.k.a. Mestre Acordeon, the leading capoeira master out west. "You can’t play soccer against a baseball team!"

But there’s a more combative spirit in the East. One day a karate and boxing and karate student walked into Vieira’s studio and without warning, attacked him. His attempt to demonstrate the superiority of his art was less than effective. Vieira damn near put him in the hospital.

No doubt about it, capoeira is tough and passionate. But it’s also a beautiful discipline, as I saw for myself at Vieira’s studio in Manhattan. There was a class of fifteen students: four black men, eight white men, two black women, and one white woman, all in their twenties, all barefoot and dressed in crisp, white shirts and white pants. Not unlike Asian martial artists, they wore cords around their waists, in colors identifying their rank. Only Vieira – a dark, handsome man in his thirties, with a serious mien and a trim, powerful physique – wore the coveted red cord of a master.

During the warm-up exercises, I noticed nothing special – just jumping jacks and leaps and stretches of the kind you’d see at a New York Giants workout in August. But then, in a classic coach’s voice, Vieira led them into the specialized gymnastics of capoeira, and the movements entered the get-down zone. They looked as if they were break-dancing. Ciao, Giants.

One move, the macaco ("monkey"), was particularly awesome. Each student leaned on one hand, arched his back and held the other hand high above his body, preparing for a backward flip or some other manner of immediate evasion. Vieira explained that the move got its name because of the monkey’s talent for scrambling, for moving fast.

Then Vieira had the students doing cartwheels, called aus, and instructed them in a compasslike spin of the legs done while resting on the palm of the right hand. The students took turns racing down the length of the room, punctuating their flight with forward kicks, called bençãos.

Pair up! Next, they were practicing fight sequences one-on-one. Pumping them up, keeping them sharp, Vieira kept up a steady stream of admonitions: "Lower, lower, I said. LOWER, damn it!… No, that’s too late. Take another shot… Keep your eyes on your opponent. Hey, would you drive that way? Don’t just hang there. Work!"

Then he led them through the basic capoeira move, the ginga. The Brazilian scholar Almir das Areias calls the ginga "the master move." And that it is. Hits, preparations for a hit and evasions all flow from this central motion. Vieira demonstrated. Flawlessly centered, he shifted his weight from his front foot to his back foot, then from back to front again, while simultaneously holding his left arm up in defense, then his right arm, in opposition to the leg positions. A motion that involves rocking from side to side while bouncing forward and back, the ginga recalls black street bopping. The black students not only mastered it immediately but poured all kinds of rhythmic gravy on it.

Suddenly, I understood what I had already been told: that the difference between capoeira and karate lies in capoeira’s blackness, that the sport comes to us from Kongo and Angola via Rio and Bahia, not Okinawa and Peking. And what happened next blew me away.

Vieira ended the class by calling for a roda, a practice game accompanied by music played on a Yoruba-Brazilian double gong (agogô), an Afro-Bahian atabaque drum, a samba tambourine and the magisterial berimbau. Roda is the Portuguese term for "circle," which is precisely what everyone formed. A roda calls for combat between two contestants at a time, in short one-to-two-minute matches. The first pair knelt before the berimbau as if it were an altar. Then they touched the floor, as if they were in Kongo or the Yoruba lands, made the sign of the cross and shook hands, acknowledging their camaraderie as well as their opposition. They cartwheeled into the center of the circle, and the battle began.

The time spent upside down, cartwheeling, handstanding, and the time spent close to the floor, hand spinning, attack evading and mule kicking, was impressive. Primary pass-over gestures interwove the bodies in three-dimensional cubism, but the phrasing was remarkably liquid. One student moved like water, flowing around each obstacle and snaring his opponent in a maze of brilliant turns. The students grew excited, and when they cartwheeled together, the spin and the sweat made them look like paddle wheels on a Mississippi steamboat.

Throughout the matches, Vieira led the class in capoeira warrior songs, which they sang in Portuguese. Everyone sang so lustily that my notebook literally began to buzz and vibrate.

Powerful stuff. It’s easy to understand why more and more Americans are digging it. They’re thrilled by a sport that fuses jazz with combat, and they feel a vague pull of familiarity without quite knowing why. In fact, many elements of capoeira should be familiar. For instance, the unison clap that routinely breaks up a football huddle is related to the continuous hand clapping in a capoeira circle. Both probably derive from the original hand-clapping, finger-popping, ham-boning "conga lines" of Kongo, the ancient Central African urban civilization.

The roots of today’s capoeira go back to the Brazilian slave trade of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, when at least a million blacks were shipped in from Kongo and Angola. No wonder Brazilian slang words for "grass" (diamba), "ass" (bunda), and "homeboy" (moleque) are pure Kongo words. No wonder the national dance, the famous samba, has a Kongo name and is a Kongo concept and move.

But the lion’s share of the Kongo impact on capoeira is in the moves themselves. Consider the upside-down positions. Kongo children still play this way today. They call the effect ta kinkindu, meaning "play upside down." According to Kongo philosopher Fu-Kiau Bunseki, "You change everything when you walk on your hands. This means you are walking in the other world."

Touching the earth before a game, kneeling before the berimbau, cartwheeling or otherwise entering the arena upside down or close to the earth – all of these are probably expressions honoring forces beyond and beneath the horizon. An early visual document of black Brazilian cartwheeling dates back to the early 1800s. It shows a moleque cartwheeling capoeira style at the head of the funeral procession for an African king’s son in Rio de Janeiro. The way the young athlete hooks his legs mirrors the way Vieira does the cartwheel in New York City today.

There are Kongo precedents for most of the capoeira moves. The evasive crouches, called cocorihna, or esquiva in Brazil, exist in Kongo games under the rubric yínama. The moving evasions with which you wheel your body out of harm’s way, like the Brazilian role move, are called bándama in Kongo, meaning "moving while crouching" – like running while avoiding the low branches of a tree. Kongo people also defended themselves with head-butting moves, called tuumba (literally "hit with your horns"), which are similar to the Brazilian cabeçada correnteiza (hitting your competitor square with your head) and cabeçada jogada (letting him have it with the side of your head).

One of the strongest inputs from Kongo is the negativa, a classic defense posture, one leg bent inside, the other extended forward, ready to trip up any enemy. "No matter what our children play," Buneski said, "you see them, from time to time, moving in this design." The low center of gravity makes the player, momentarily, almost invulnerable. We know from an old print that negativa was played in Bahia as early as the 1820s, and we see it today as a basic get-down defense stratagem.

Of course, most of these moves originated in friendly sparring. "In Kongo, to fight against your peers in the village is bad form," said Buneski. "We came to play, not fight." João Pequeno, one of the leading teachers of capoeira in Bahia today, drove the point home. "When the Africans did capoeira, ginga was a form of dance," he said. "In Brazil it turned into a fight."

Hell, yes, it did. Just imagine doing a ginga by the light of a full moon in Kongo and suddenly finding yourself on the auction block in Rio. The moves got rowdy and bloody and stayed that way. By 1820, the police of colonial Rio were actually assigning officers to known players of capoeira, just in case.

Back in Kongo, the elders played a musical bow (the lungungu, later renamed the berimbau in Brazil) as an aid to meditation and an accompaniment to rituals for initiations and births. It’s said that in Brazil the musical bow was added to capoeira to disguise it as a harmless sport or entertainment when the police were watching. And the black elders may have introduced it to keep matters from getting out of hand. To this day, if players lose their temper, the master immediately separates the fighters by placing the sacred bow between them.

All this history and moral nicety was lost on the white authorities. Well into the twentieth century, they associated capoeira with crime. Enter, in the early 1930s, a black man in Bahia known as Bimba (Manoel dos Reis Machado). Fed up with all this racist nonsense, he founded the first capoeira academy in 1932 and institutionalized the tradition by giving it rules and dignity.

Like Duke Ellington transmuting blues into symphonic structures, Bimba polished the improvised Kongo-derived street moves into a choreographed martial art – and an efficient fighting technique. His genius was to push in two directions at once, Creole Brazilian and African, achieving a brilliant synthesis. He kept the Kongo get-down stratagems, added feisty elements of Creole street fighting and stirred in more pepper from the Kongo coast with the myriad modes of batuque trip-‘em-up. (One example of batuque is the banda trasada. A player hits his opponent’s thigh as hard as he can with his knee. Then, before the opponent can recover from his charley horse, the assailant places his foot behind the opponent’s, pulls back sharply and puts him out of his misery.) Armed with this multi-cultural arsenal, Bimba could bring down an opponent with three swift hits.

Bimba was as witty as he was tough. Writer and capoeirista Alves de Almeida reported that if there was a knock at the door while class was in session, Bimba might play on the berimbau the "mounted police" beat, a code that loosely translates as "Watch it! Potential fuzz at the door." And when his charges played too rough, he sometimes switched to a more laid-back Benguelan beat.

Bimba, doctor of mind and body, died in 1974. Bira Almeida and Bimba’s other star students, like Cascabel, Onça, Camissa, Sacy, and Camissa Rôxa, kept their master’s style alive. They did missionary work in the industrial south of Brazil, particularly São Paulo, and they did it with a vengeance. They were pissed off. In the mid-Seventies, the popularity of karate films was threatening to kill off capoeira in the country of its origin. So the Bimba elite went around to karate schools, challenging each master. Guess who won. Their victory planted the seeds for today’s capoeira renaissance.

From São Paulo and Bahia, capoeira traveled to the States. Jelon Vieira and Loremil Machado came to New York City in 1975. Their first New York gig was performing capoeira on Broadway in The Leaf People, a play about Brazilian Indians. "No one knew what the hell we were doing," said Machado, who eventually brought Creole-Yoruba chants from black Bahia, along with capoeira and Rio samba, to S.O.B.’s, New York’s premier Brazilocentric nightclub. Since 1982 he’s been performing there at least one weekend a month.

In 1979, Bira Almeida settled in the Bay Area, after a friend who had studied with him in Brazil urged him to come and spread the muscular largess among norteamericanos. Almeida’s influence now extends into the Rocky Mountains and beyond. One of his best graduates teaches capoeira in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and another of his students teaches in Denver. There are also capoeira instructors holding forth in Seattle, Los Angeles, Las Vegas, Portland, Oregon, and Washington, D.C.

But New York remains the epicenter. Capoeira keeps popping up on Broadway, in SoHo nightclubs, and on local TV. The city is also producing some of the best American-born teachers, like Herb "Pilao" Kerr and Harry "Carbao" Young, while it continues to attract Brazil’s brightest stars. One of the most dynamic is Itaborá Ferreira, an ex-marine turned capoeirista. He divides his time between serving as a bouncer at a Manhattan disco and teaching capoeira. He instructs his students in the most direct way: move wrong and he whomps you so you’ll get it right next time.

So far, despite the increasing popularity of capoeira, lessons are downright cheap – four to seven dollars a class – and very competitive with the Asian martial-arts schools. That’s mainly because many capoeiristas have parallel careers, and most of them are doing it for love. But there are more compelling reasons for taking up capoeira:

Body building: "It takes a lot of stomach," said Machado. Capoeira’s constant twisting, bending, and jackknifing develops the "washboard" abdominals that advanced capoeiristas wear like armor around their waists. "And it gives you strong arms ‘cause you’re upside down a lot," he said. The cartwheeling and handstanding build what Vieira calls "jaguar hands."

Mental and physical discipline: "I’m from Wall Street," said one student. "The honest combat gives me perspective."

Cultural enrichment: Is there any other sport that teaches you to sing in a major Romance language, play an ancient instrument, dance in a Kongo-Brazilian mode, and kick your rivals on their ass in all the same format?

Sex appeal: Bimba had more lovers than he could handle, and one American master had a lover who offered him a castle in Europe and unlimited American Express if he would leave capoeira for her. He refused.

Eternal youth: In his book on Bahia, novelist Jorge Amado maintains that if you stick with capoeira, you can take down young bloods way into your seventies. God knows, I’d like to believe that. So I tried capoeira myself.

Thankfully, my main sparring partner was nice enough not to laugh when

I made like the world’s first perfectly square wheel. But one day my opponent

turned out to be a cornerback from the Yale University football team. When

he faced me in his ginga with a wolfish grin, I felt my blood run

in the wrong direction. Every move he made was a thousand times more flexible

than mine. But I did manage one good kick that made the big bastard duck.

Most importantly, I survived. And survival in postmodern America is good

enough for me, baby.

Robert Farris Thompson is Master of Timothy Dwight College at Yale University. His books include Face of the Gods: Art and Altars of Africa and the African Americans (New York: Museum for African Art, 1993).