By Robert G. Denig

Reprinted from Outing, XXI: 2 (November 1892), 83-91. Ed. Note: Compare with "Shooting in Japan," jcsart_hartman_0301.htm and the information presented at http://www.netwizards.net/~eclay.

"Every time his bowstring twanged an enemy fell."

So it was said of Yoritomi, the ablest Shogun and greatest ruler that ever lived in Japan – he who founded the dual system of government by making himself the first dictator, with his seat of government at Kamakura, while the Mikado was maintained a ceremonious, dignified, but unapproachable captive at Kioto.

This important event in the history of the Japanese was the outcome of a great battle fought in 1185, when Yoritomi, the leader of the powerful Minamoto family, overthrew the Taira.

It was a naval battle between great high-pooped junks, loaded to the water’s edge with warriors. But, strangely enough, it was a naval battle that owed its victory, if we can believe the chronicler, to the prowess of the bow and arrow.

The iron bolts shot from the longbows of the Minamoto archers are said to have gone crashing through the planking of the Taira junks, scuttling them as effectually as the more modern rifle ball. As the riddled hulls sank, they left the brave warriors, swimming in a bloody sea, easy targets for the showers of relentless arrows of the Minamoto.

Then began the long line of the Shoguns and the imprisonment of the Mikados. The wars and intrigues of succession were entirely confined to families aspiring to the Shogunate, for although several families had the honor of a line of Shoguns, the Mikados descended, century after century, in an unbroken succession and without loss of prestige. The last of the great Shogun families was the Tokugawa, who were driven from power in 1868, when the Mikado, after seven centuries of mock rulership, was restored to his true position of emperor, on the flight of the defeated Shogun.

The Western powers would not recognize Japan’s right to close its own ports, and its brave warriors were made to feel the combined effects of modern civilized war in the bombardment of Shimenoseki by an allied fleet [in September 1864].

Civilization marches arm in arm with the art of killing. And though this unequal conflict with civilized powers was a severe lesson, it was one cheaply bought, for the men of Satsuma discarded at once their native weapons and clumsy armor and, equipping themselves with American rifles, made war on the Shogun.

This revolution of the people of the south culminated in a great battle at Tokio in January, 1868. A strange battle, where the weapons of the middle ages attempted to hold their own against Remington breech-loaders, a battle between the ancient warrior and the modern soldier. A battle, the issue of which has changed in a few years the thoughts and habits of a whole nation; feudalism ceased to exist; the clash of the keen sword of the Samurai and the twang of his bowstring were silenced forever.

Up to this event, known in Japanese history as the "Restoration," the national weapons of Japan were the longbow, the sword, and the spear. The best artists and artisans had for centuries devoted their time and talents to perfecting and ornamenting the sword, mysterious and secret rites were observed in its manufacture and "christening." It is one of the sacred emblems of sovereignty.

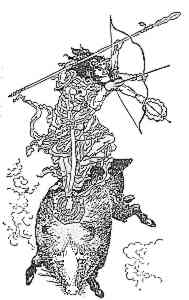

The spear, though also highly developed in the way of ingenious and effective spearheads, was the least important of the three. The bow and arrow, naturally the most ancient war implement, was also the most universal. The hilly nature of the country, as well as the walled towns and formidable castles of the Daimios, that must be sieged and stormed to be taken, made the bow not only a necessary but the winning factor when the opposing forces assumed the proportions of armies. In time of peace it was the favorite weapon in the chase and furnished amusement in interesting contests of skill and accuracy. Marishtin, the six-armed "God of manly sports," is pictured as poised on the back of a wild boar equipped with bow and arrow, a spear, a sword and the baton of the referee of the wrestlers.

Marishtin, the God of Manly Sports.

The earliest examples of the metalworkers’ labors in Japan are the bronze arrowheads, of various designs, that have come to light through the researches of the archaeologist, principally from the tumuli of Kozuki. An early Japanese chronicler says that metal-founding was brought from Korea in 97 B.C., but the bronze and even iron arrowheads – for they seem to have had no real bronze age – anticipate that.

Tradition goes back to the mythical period and tells of exploits in which the bow played a great part, in the time when the gods of Japan quarreled, made love, and fought dragons, rikins and monster snakes. Buddha himself, in the Japanese version of his six years’ wanderings, was armed with the bow of mercy and the arrow of compassion. When Mara, the king demon, tempted Buddha, in the form of a beautiful woman, he was struck on the head with the arrow of compassion and forced to reassume his real shape, and he fled vanquished. On the spot where Buddha found the sacred truth he buried the bow and arrow, and there sprang up a temple of gold, still, by the very devout, believed to exist.

A curious proof of the antiquity of the bow as the principal national weapon is that the term for enforced labor of men for the government, [according to traditional accounts] instituted 50 B.C., by the Mikado Sujin, means literally "Bow Point." This obligatory labor of so many days each year, though not always of a soldierly nature, was originally no doubt a forced enlistment of some specified duration under the banner of the Mikado, like the service required of men in Europe.

Yumi-ya, bow and arrow, is used as synonymous with arms. And though a Samurai might swear by his sword, yet the most binding oath (and the one used officially) was always sealed by solemnly breaking in twain an arrow as he pronounced the words of the oath.

A target with an arrow piercing the bull’s-eye, which one so often sees in Japan, is the common symbol for a great success; in other words a great "hit." The merchant who is driving a big trade, the theatre that is drawing crowded houses, and the most popular teahouse, all affect this symbol.

One superstition regarding the bow, universally and good-naturedly believed in, as we believe in the virtues of a horseshoe, is that the twanging of a bowstring will frighten ghosts and evil spirits from the house.

The bow often appears in the hands of the gods. The guardian deities at the gates of Shinto temples, called Udajin and Sadaijin, are armed with bows. At the temple of the Sun Goddess at Ise, the Mecca of the Shintoists, the native religion of Japan, one of the ranking deities next to Ama-tersau-no-mi-Kami, the presiding goddess, is Tajikara, or the strong-handed man, whose emblem is the bow.

And if we are to believe their wonderful tales, it took a strong-handed man to use an ancient bow. That of Hidesato, a tenth-century hero, required the strength of five men to pull it. He, however, sank an arrow five feet in length up to the feather into the iron forehead of an enormous centipede, a fabulous creature that carried in each claw a flaming torch. When the arrow pierced its brain, the lights went out and the monster fell to the earth with the noise of thunder. Another renowned warrior shot one night at what he thought was a tiger; on visiting the spot the next morning he found his arrow embedded several inches in the solid rock.

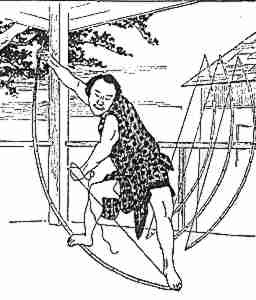

The bowmaker.

Their books abound in stories of marvelous feats with the bow and of miraculous escapes. The arrow turned aside, or breaking in the air, or cut in twain with the sharp sword while in flight, or caught in the hand and returned with deadly aim by an expert bowman. The famous Go-go-ro, of Kamakura, in the siege of Tori-no-uni, is said to have received an arrow in his left eye; without stopping to take it out, he shot a shaft in reply that killed the enemy who had wounded him.

A favorite theme for the brush of the Japanese artists is a scene from the life of the Empress Jingu Kogu (literally the empress of supernatural achievements), [traditional dates] 201-269 A.D. This fair Empress of Japan is accredited with the conquering of Korea. Before starting out on this expedition against Korea, she angled at the seashore of Kashii, using her bow as the fishing rod and the string as a hookless line, baited with a single grain of rice, saying, "If I am to be successful, a fish will be caught." Behold, a fragrant trout was dangling at the end of her bowstring. She became the mother of Hachinan, the God of War.

The Empress Jinga Kogu, "Mother of the God of War."

At the time of the rise of the Minamoto family, in the twelfth century, the bow seems to have reached a high state of perfection, both as to manufacture and skillful use.

The peculiar shape of the bow is not from caprice, but from a scientific consideration of every element necessary to make a perfect weapon. When in use the greater portion of the bow is above the bow arm. In one, seven feet in length, the arrow is "notched" on the string two feet six inches from the lower horn, or one foot below the center.

This device, for the same length of pull, produces a greater tension on the string, but does not otherwise affect the flight of the arrow; for the return of the bow ends through unequal arcs to their normal position, is nicely arranged for by the difference in size of the compensating or backward curves of the bow at the extremities. The Japanese being short in stature, the above described peculiarity of construction became an additional advantage for manipulation on horseback and in the kneeling position behind the low parapets of a daimio’s castle.

The bow is made of carefully selected, thoroughly seasoned mulberry, incased on either side by strips of bamboo well toughened by fire. These three pieces are bound firmly together by fine thread like withes of rattan; the tips where the string is secure are covered with smooth lacquered sharkskin. The whole is covered with many coats of perfectly polished lacquer, which seems never to crack and renders it absolutely secure from any atmospheric influences, and it lasts for ages. This impervious, imperishable lacquer is one of the secrets of their perfection. As to durability, strength, lightness, elasticity and accuracy, they have never been surpassed.

The interesting similarity of the histories of England and Japan, so often cited in other respects, is once more patent in the history of the longbow. England is the only other country in which it received similar attention and developed into a successful military weapon. The battles of Crecy, Poitiers, Agincourt, etc, were won by prowess of English longbow men. On the Continent the short range, clumsy and inaccurate crossbow, or arbalest, was the prevailing arm. The longbow required strength and continual practice, and numerous acts of parliament enforcing the use of the longbow testify to its importance. Every English subject had to exercise with it and teach the use of it to every male child or ward. It was forbidden for any man over twenty years of age to shoot at a mark nearer than 220 yards with a flight arrow, or 140 yards with a sheaf arrow.

In the same way was the bow fostered in Japan. After the establishment of the duarchy by Yoritomo, the training of a multitude of warriors was a necessity, for the rule of the shogun was based upon the power of arms. Arms had been modified and perfected in every way; through the severe experience of actual conflict; their further improvement was not possible, victory now depended upon the skill and bravery of the warrior. Hence again the necessity of a standing army – in other words the hatamoto, or special vassals of the Shogun, and the samurai, or "two-sword" men. The "two-sword" men, though they might belong to the Shogun, were generally in the train of a daimio.

The hatamoto and samurai, as a mater of policy, and that their sons might be proud to inherit the honorable profession of soldier, were elevated to the third rank in the social system of the country, there being eight divisions of society. Bow practice, among other accomplishments, was rigidly exacted of them, and for special training in the arts of war, schools for fencing with sword and spear were opened in all parts of the kingdom. Frequent tournaments for archers, with valuable prizes for the victor, were supported by the Shogun and the more powerful daimios; these were in reality schools for archery. The favorite places for these tournaments were in the grounds of the principal temples of the Damioate.

Every visitor to Kioto will remember the archery grounds at the temple of San-jiu-san-gen-Do. This curious temple, founded n the twelfth century, contains one thousand life-size images of the "one-thousand-handed" Kwannon, arranged in ten tiers. The exterior of the building is surrounded by verandas on four sides, the longer sides are 389 feet in length. It was, as the guide will tell you, "before time," a famous resort for expert bowmen. In 1686, one of the retainers of the Prince of Ki-shiu shot 8,133 arrows out of 15,053 from end to end and embedded each in a target. A marvelous feat and well worth recording, for the overhanging eaves of the veranda are but eighteen feet above the archer’s head, making it a point-blank arrow-shot of 130 yards.

The ya, or arrow of the Japanese, received great attention; the shaft was of cane or bamboo, winged with three feathers and varied much in length, the war arrow averaging about three feet. They were dignified by names from the design of the arrowhead or to indicate their purpose. "Armor piercer," "Knife prong," "Willow leaf," "Bowel raker," "Frog crotch," "Turnip top," etc. The "knife prong" and "frog crotch" were intended to cut the helmet-strings and armor-lacing of the enemy, and incidentally their throats; the "armor piercer" was well designed for that work, being made like a machinist’s center punch and of the hardest steel. The murderous "bowel raker," once striking the victim in the region indicated, deprived him of the honorable distinction of performing hari kari (suicide by disemboweling), in case of defeat, for the blow of the arrow was equivalent to that fatal cut.

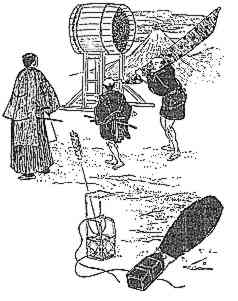

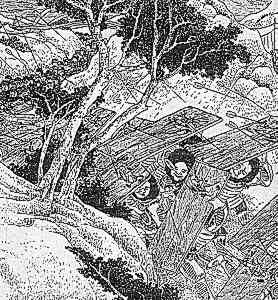

Preparing for battle.

Burning arrows were used to carry fire into the enemy’s stronghold. The ya-bumi was a message arrow constructed for long flight; the shaft was painted white to attract attention. The poisoned arrow, still used by the Ainu of Yesso [Hokkaido], was prohibited by the rules of war, as was also the barbed arrow

The last mentioned weapon was excessively cruel, the barbed point being but loosely attached to the shaft, became detached upon penetrating the flesh and the point to be removed must be cut out. All their arrowheads were of exquisitely wrought steel, perfectly tempered, and in some instances engraved or beautifully inlaid with precious metals. Many famous makers were of the Daimoate of Echizen, notably of Takebu, and the excellence of their vicious steel points lives now in the superior quality of their domestic cutlery, to which use their forges have been put since the adoption of western civilization.

Arrows often bore the name of their owner, that the enemy might know to whom they were indebted for a skillful shot. In one of the many battles between the Taira and Minamoto, the arrow of a certain bowman named Hachiro was found in the death wound of Hyoda, Taira’s greatest warrior.

That Hachiro might be honored among his brother warriors, the fatal shaft was returned to the Minamoto camp. When brought before the Shogun, Hachiro was not to be outdone in chivalry, and, after expressing satisfaction that his arrow had slain the powerful Hyoda, refused the proffered honor, saying it was but a random shot in the thick of the battle, and he would accept no reward for the chance that had caused his arrow to pierce the neck of so distinguished a man as Hyoda.

We have found no evidence that the Japanese Cupid was armed with bow and a quiver of love darts, yet that the arrow at times bore a message of love seems certain from a legend connected with a temple in the tea district of Uji. A maiden named Hime was strolling by a secluded stream; a red arrow winged with duck feathers floated towards her, so she picked it up and carried it home. It was a message of love, as she gave birth to the god still worshipped.

Quivers and bow in case.

The quiver, ya bokuro, especially for the common bowman, was a light affair of bamboo and paper slung diagonally across the back. For the rich or renowned warrior, it was often an elaborate but clumsy case of horse or deer skin died black.

Japanese archers, like the ancient English bowmen, were occasionally armed with a long-handled wooden mallet, with which they dispatched the foe at close quarters; usually, however, his additional weapons, if any, were swords. The archer, proper, was not always armored, but carried as a protection a wooden shield, ta-ta-i-ta, of oak two inches thick, fifteen inches wide, and three or four feet in length, which from superstition as well as for ornamentation, was carved or painted with the head of the war god.

Ta-ta-i-ta – the archer’s shield.

In preparing for battle, these shields were propped up on the ground to form a palisade. The warriors knelt behind them and awaited the signal for the yawase, or volley of arrows, fired by both sides at the commencement of every battle.

In case of retreat, these shields were carried on their backs and received the shower of the enemy’s arrows sure to follow them, being afterwards exhibited by the lucky warrior with an array of embedded shafts as proof of his individual prowess.

Raining arrows – the retreat.

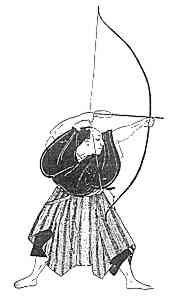

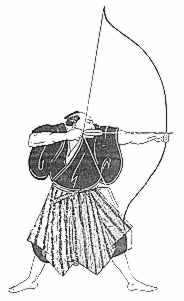

The manner of pulling the bow, well shown by the spirited sketches by our artist, appears, when first witnessed, to be attended by a superfluous amount of posing, so extremely picturesque are the movements; yet they carry with them a conviction of skill and power. After a little practice one finds each and every motion has its use, from the time the arrow is notched until it strikes the target.

First position.

In the first position, that of notching the arrow, the feet are braced well apart, the body bent forward to relax the muscles, and the point of the arrow is inclined towards the ground.

Second position.

The bowman then, with great deliberation, raises the bow to the second position of aiming, both hands high over the head, fixing his intently upon the target.

Third position.

The bow is then slowly lowered to the final position. The instant this is reached, the string is released, the arrow flies through the air, and the bow spins around in the hand until the string strikes against the back of his bow arm. This trick of allowing the bow to whirl in the hand gives a most graceful finish to the whole operation.

Fourth position.

The string is pulled by the thumb, which in turn is held in place by the two first fingers that grasp the end of the thumb; they, like the thumb, are gloved. This method of holding the string admits of as strong a pull as the old English method of using he fingers, and gives a quicker release.

The notch of the arrow is pulled to the ear, a natural result of lowering the bow from overhead – a system that also brings into play the muscles of the shoulder and the back, for the bow-arm is all the while fully extended and rigid.

The ancient Persians, as shown by the sculptures at Persepolis, like the English and the Japanese, drew the notch to the ear. The manner of loosing the string peculiar to the Japanese, as just described, has many arguments in its favor as against the more universal method known as the "Mediterranean loose," where the thumb plays no part in the release.

The old Greek method of holding the arrow with thumb and finger and pulling to the breast was incapable of accomplishing the feats performed by Japanese warriors, and moreover had the disadvantage of rendering the fabled Amazons at best but left-handed beauties.

Some Japanese feats have already been mentioned. A well-authenticated shot of long range accuracy was that of Nasuno Yo-ichi, who pierced the Hinomaru (rising sun) on a warrior’s fan, at the distance of 700 yards, hoisted by the enemy as a challenge.

Sewing the wings of a flying bird.

A sportsman’s most perfect "hit" was to sew the wings of a flying bird – that is, to impale the two wings on an arrow without injury to the bird. Robin Hood is accredited with this capacity.

The great feats of the Japanese bowman, interesting to all lovers of archery, are now no longer to be witnessed.

In 1871, the edict went forth that abolished feudalism by retiring the Daimios to private life. The samurai were disbanded and found their two swords but useless ornaments, and the proud bowman degraded his bow into a humble implement for beating cotton. Happily, the practice of archery as a pastime still exists to a large degree, and is, as it deserves to be, more popular than the art of fencing.

Archery game.

A common adjunct to many Shinto temples is the yaba, or place for archery, where the enthusiast, native or foreign, can display his skill or be heartily laughed at for his lack of it. By the yaba is meant ranges from 100 yards to 200 yards, equipped with bows from one-half inch to one inch, from five feet to seven feet in length, and with a pull of twenty-five pounds to one hundred and fifty pounds.

The keeper may be an old woman minus eyebrows and with blackened teeth, but the dark-eyed maiden may bring the tea; she may be attractive and pretty, with winning ways and sweet smile. If you are good-natured and awkward, she may, with a merry little laugh, slip a fair arm and shoulder from her ample-sleeved kimono and give you a few lessons in Japanese archery that will convince you that cupid with his bow and arows is an active member of the Pantheon of Dai Nippon.