Copyright © Joseph R. Svinth 2001. All rights reserved.

Although Yasuji Fujita weighed only about 150 pounds, he was ranked

4-dan in judo and before coming to America he had been the captain

of a Meiji University judo team. So as a wrestler he was not out of his

league in America. For example, when he met 195-pound Jimmy the Greek at

Seattle’s Nippon Kan Theater on Wednesday, October 23, 1929, the Japanese-American

Courier reported:

Before the loud acclamations of the [mostly Japanese] crowd had died down the Japanese again threw his opponent to the mat with a judo hold and kept repeating the tactic until it was evident that the Greek was well-nigh exhausted. Then Fujita threw him for the final fall and holding the giant down won the match with an arm hold.

In taking the second fall, the match was contested in the time-honored

catch-as-catch-can style. This time Fujita was faced with some difficulty,

but the Japanese … displayed some surprise by his adeptness in working

half-Nelsons, toe-holds, and armlocks… After twenty minutes of this wrangling

Fujita, turning his man over, took an arm lock and pinned his man…

In a third match at the Nippon Kan, this one on December 6, 1929, Fujita got an armlock on Big Zep to win the first fall, stripped off his jacket and lost the second fall, then put on the jacket and an armlock to win the third fall.

After leaving Seattle, Fujita wrestled throughout Southern California and the upper Midwest, where he was mostly known as Iota Shima. His home base, though, was Ohio, and during April 1931 Fujita was reported beating Art Perkins.

Fujita returned to Seattle during November 1931 and June 1932, and as all Japanese looked alike to the average North American wrestling fan, hardly anyone outside the Japanese community remembered Fujita’s 1929 visit. Therefore he caused a stir by moving from the preliminary bouts to the main event after just three "victories." As the Seattle Post-Intelligencer put it on November 30, 1931:

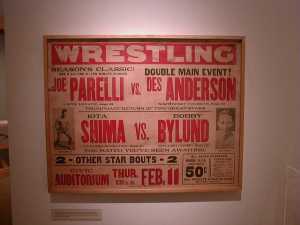

Shima, brought here from Cincinnati, has his eye on Joe Parelli, the tattooed former middleweight champion. But he’ll have to dispose of Chase first, and then chase Parelli.

Fujita returned to Columbus, Ohio, in August 1932, and during the next six weeks he beat Gordon Arquette, Jack Domar, and George Gable, and lost to Wildcat McCann. However, in October 1932 Fujita relocated to Japan. The reason was that in May 1932 US immigration authorities had arrested him in Detroit for visa violations. Although released on bail and allowed to keep wrestling until his trial, the US Department of Labor had no trouble showing that Fujita had entered the US on a student visa. And, while he audited two semesters at California’s Whittier College during the 1926-1927 academic year, since then he had mostly worked as a professional wrestler. Then, during 1927, he began working as a professional wrestler. Since he didn’t have a work permit, this was illegal. So, in the words of the Japan Times, the judge concurred with the "Department of Labor that Mr. Fujita’s scholastic enrollments were not in good faith and that his real motive for being in the United States was to make money as a wrestler and not to improve his education in other lines."

Still, a college sheepskin is no substitute for acting ability, and upon returning home, Fujita went into politics and eventually became the mayor of his hometown.

END NOTES

EN1. Shinkai exaggerated only slightly: according to the Civic Auditorium’s published figures, wrestling provided 18% of the facility’s annual revenue in 1930 whereas ice skating and hockey provided 23%. (Post-Intelligencer, May 21, 1931.