Copyright © EJMAS 2001. All rights reserved.

A note on transliterations: Although this article uses pinyin to transliterate technical terms, personal names are presented using the spelling by which the person is (was) best known in English. Book titles are likewise presented as on their covers.

Training manuals are books or manuscripts that teach the principles,

techniques or forms of a system, and as such are separate from books that

discuss the history of martial arts or works of fiction. Xing-yi quan is

one art where training manuals have existed for several hundred years,

and that history is the focus of this article.

Xing-yi Quan

Xing-yi quan means "form-mind boxing," and is romanized as xing-yi (pinyin), hsing-i (Wade-Giles), and hsing-yi (Yang Jun-ming’s transliteration). Stylistically, it is one of the three internal Chinese martial arts, the other two being bagua (pa kua) and taiji (t’ai chi). Structurally, it is characterized by its seeming simplicity: the system consists of a limited number of forms and techniques that are drilled in series of short forms. However, whatever the system lacks in variety, it makes up for in depth, requiring the student to make a long and intensive study of the basic motions of combat. It is also undeniably practical, having been the system of choice during the late Qing and Republican periods for people such as convoy escorts and bodyguards who made their living fighting.

Xing-yi has two major subdivisions, the Hebei-Shanxi tradition and the Henan tradition. The Hebei-Shanxi schools are much more prominent both in China and in the West. Their core training consist of the 5 element fists and the 12 animals forms. Meanwhile, the Henan schools, although far less prominent, probably represent a more accurate/faithful version of early hsing-i. Their core training consist of 10 Animal forms that are different from the 12 Animal forms of the Hebei-Shanxi lineage. The Henan branch is also known as Muslim xing-yi. The reason is that the historical founder of xing-yi, Ji Ji Ke, had two major students, who in turn founded the Hebei-Shanxi branch and the Henan branch. The Henan branch founder, Ma Xueli (1714-1790), was Muslim, as were his family and all his students. Since the Henan branch of xing-yi tended to stay within the Islamic community, it subsequently became identified as a Chinese Muslim ("Hui") martial art.

At any rate, the development of modern xing-yi is attributed to Ji Ji

Ke, circa 1750, and the subsequent history of its training manuals can

be usefully divided into four periods: the legendary period, the hand-copies

period, the Republican period, and the modern period.

Legendary Period

The legendary period is here defined as the period for which no "hard historical evidence" exists, "hard historical evidence" being defined as extant copies, having the work mentioned in library catalogues of the time, or having the work quoted or used in some other contemporaneous works.

For xing-yi, the legendary period starts with the Southern Song General Yueh Fei, who was a noted spear master. For many centuries after his death the general’s art was lost, but subsequently it was rediscovered by Ji Ji Ke, a martial artist living during the early Qing dynasty (circa 1750).

According to one version of this story, Ji Ji Ke was on a trip; night began to fall and it started to rain. Therefore Ji took shelter in an old, dilapidated temple dedicated to General Yueh Fei. Within the abandoned temple was a statute of Yueh Fei which Ji took a close look at. He noticed that it was cracked, and through this crack he saw something hidden inside the statute. His curiosity aroused and his sense of reverence diminished, he took his sword and broke open the crack. Within the statute he found a hand-copied manuscript called "Yueh Fei’s Six Harmony Xin Yi ["Mind-Intent"] Boxing Manual." Ji studied this manual and relentlessly practiced its teachings and thus became the historical founder of xing-yi quan.

Unsurprisingly, there are several versions of this story. In one, Ji finds the manual in a cave while in another the stock "mysterious Taoist stranger" presents the manual to him and then disappears. And, while one version or another of this story is recounted in many xing-yi manuals as historical fact, it is more likely a legend. After all, paper manuscripts generally don’t survive several hundred years embedded in statutes. Furthermore, there is a common desire in Chinese martial arts systems to link their founding to an important or mysterious figure. The three most common choices for "founders" being General Yueh Fei, the sage Chang Sung Feng, or some mysterious Taoist. (If you want to add further mystique, you can say the Taoist monk was either an albino or a dwarf or was 200 years old or some combination of those.) Modern historians generally disregard such claims.

Note: Although there is a work known by the same title as the legendary

work, Yue Fei’s Six Harmony Xin Yi Boxing Manual, martial arts historians

are sure that the extant work is a far more recent creation.

Hand-Copies Period

Xing-yi’s oldest known hand-copied manuals date from the late Qing dynasty, that is the mid-eighteenth century. Such training manuals were hand-copied either from other hand-copies or from notes made of a martial arts teacher’s lecture. These early training manuals tended to be quite basic but were sometimes illustrated with line drawings.

Examples of hand-copied manuscripts from the early Republican period

These early texts were largely useless unless one had already trained in that school, the reason being that they tended to consist of a combination of shorthand notes, mnemonic rhymes, and esoteric philosophy. But that wasn’t a problem because such texts were intended exclusively for students of that lineage, and the language used was intentionally arcane, symbolic and otherwise vague. These are the real life "secret kung fu manuals" that figure so often in martial arts fiction and movies.

These manuals, as the name implies, were hand-copied from student to student. Some of the manuals were "books" in the sense that the content was standardized. In other words, they contain the same mnemonic poems, the same symbolic images, and the same rhymed couplets. Others can perhaps better be described as student notes which tended to be unique to that student, that teacher, and that school.

A few of these hand-copied xing-yi manuals still exist in private collections. A variety of factors have made them extremely rare. Oftentimes there would only be one copy of the school’s training manual. If a master was not satisfied with or mistrusted his disciples, then he would not make the school’s training manual available for copying. If that was the case, then the transmission of that training manual ended when that master died. Other manuals were destroyed through fire or war, and still others were intentionally discarded during the Cultural Revolution, a time when the simple possession of such an item could cost the owner his freedom, or perhaps even his life. And probably most were simply thrown out by disinterested heirs who said, "Oh, this is just one of Grandpa’s old notebooks. It doesn’t make any sense, something about martial arts, so into the trash fire it goes."

An alert reader might wonder, since most pre-modern xing-yi practitioners couldn’t read, what was the point of the training manuals? For one thing, in those days the simple possession of a manual had a certain talisman-like quality. For another, the person who had physical possession of such a book was viewed as being legitimately within that school or lineage and was perhaps viewed as having seniority within that school. The training manual was therefore a kind of symbol of authority. Finally, one should remember that even the smallest village usually had someone (a Buddhist priest, a Muslim imam, a low-level official, or a retired scholar) who could copy a manual for a fee, or, for that matter, read it aloud to the interested martial artist.

For an idea of what these hand-copied manuals contained, refer to the

section in Tim Cartmell and Dan Miller’s book Xing Yi Nei Gong entitled

"Xing Yi Quan Written Transmissions." These "Written Transmissions" are

to a large extent based on hand copied texts. Wang Jin Yu and Zhang Bao

Yang, who assisted in collecting this material for the book, have made

an important historical contribution by collating and organizing this early

material.

Republican Period

The Republican Period, which extended from the final fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1911 to the end of the Chinese Civil War in 1949, was a kind of Golden Age for xing-yi training manuals. The reason was the arrival of commercial publication and photography.

Sun Lu Tang

Until the Republican period, xing-yi manuals were, to a greater or lesser extent, "secrets." (The phrase in Chinese is "closed door," and refers to a student or a teaching that is not open to the public.) This sense of secrecy is reflected in the fact that the hand-copied training manuals are to a large extent meaningless unless one already is familiar with the system. Put most simply, you can’t teach yourself xing-yi based solely on a hand-copied training manual.

The Republican period marks a new attitude toward learning, and the Republican period xing-yi master and author Huang Bo-nien summarized this change when he wrote: "Unfortunately, the fist forms in our country [China] were always kept secret. They were always taught orally and never recorded in written form. This is why many excellent fist forms were lost. This is due to the ancestors’ stubbornness, fears, lack of trust and suspicions. This is the biggest obstacle in the martial arts world." Statements like this, coming from a noted teacher such as Huang, clearly mark a major change in approach.

The result is an increased sense of openness, and the training manuals written in this period give relatively full and comparatively clear explanations of how to practice xing-yi. There are few, if any, distortions in these books of either the theory or actual techniques, and Jiang Rong-qiao’s xing-yi manuals in particular seem clearly designed for self-teaching with or without a teacher’s guidance. Indeed, several manuals come out and state, in essence, "Although learning from this book is not as good as having a teacher, the student can still gain great benefit and make progress in learning the art." The question of whether anyone in any period can learn xing-yi from a book is a debatable issue that lies outside the scope of this article, but suffice it to say that in those days, self-education was not deemed impossible.

Republican period manuals also differ from hand-copied manuals in other ways. For one thing, they tend to stress the importance of physical health and martial spirit as a public policy. This is a reflection of the broader goal of the Republican government, which was to strengthen the Chinese people and end the image of Chinese as "the weak men of Asia." This is in turn a part of a broader sense of nationalism that was becoming prevalent in China at that time.

By way of example let me quote sections from two prefaces of two well-known books of the time. In his preface to The Study of Xing Yi Boxing, Sun Lu Tang wrote:

Another factor in the changing viewpoint was the creation of public martial arts associations throughout China. Such associations had a number of goals including making Chinese martial arts, including xing-yi, widely available to the public. Toward that end, books were commissioned as a way of systematizing what was being taught.

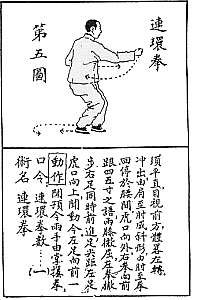

Page from Jiang Rong-qiao’s 1934 text showing the fourth move of the set.

Since public dissemination of the martial arts was seen as representing

sound government policy, especially in the area of physical education,

early publishing ventures were often financially sponsored by government

agencies. Which government didn’t really matter, either -- at various times

the Republicans, Kuomintang, Japanese puppet regime, and Communists all

underwrote martial arts associations, tournaments, and books.

The Authors and Books of the Republican Period

The most influential Republican-era xing-yi manual was written by Sun Lu Tang. Sun (1861-1933) was a rarity in any age in that he was both a skilled martial artist and a talented writer. (As a practical matter these two skills rarely go together, and the fact remains that many, perhaps most, highly skilled martial artists desperately require editors or ghostwriters.) A self-educated man, Sun knew quite a bit about Chinese philosophy, Chinese literature, calligraphy, and various Taoist qigong (chi kung) practices. This knowledge combined with his martial arts expertise put him in a unique position to write on xing-yi.

His first book, published in 1915 and entitled Study of Xing-yi Boxing, is considered by many to be the single most influential book ever written on the subject. This influence is based on a number of things. First and foremost was Sun’s unusual combination of literary and martial skill. Thus he could explain things in a way that others could follow, and generally agree with. Moreover, his book was also the first to feature photos, to discuss the relationship between xing-yi and Chinese philosophy, to provide detailed instruction on the actual performance of the techniques, and break the wall of secrecy. In other words, this book was written for public consumption.

Stylistically, the book describes the five form fists, a set linking the five fists (Lien huan), two different 2-person sets, the 12-animals forms and a set linking the 12-animal forms (Za Shi Chui). It is illustrated with photographs of Sun doing the solo exercises and line drawings of the two-person sets. An excellent translation by Albert Liu and edited by Dan Miller is available as Xing Yi Quan Xue: The Study of Form-Mind Boxing. The photos and drawings accompanying this translation are the originals.

If Sun Lu Tang was the most influential writer and publisher of the period, Jiang Rong-qiao (1891-1974) was certainly the most prolific. Jiang trained in a number of Chinese martial arts, including xing-yi, under Li Tsun-I and Zhang Zhao Dong. However, there are three things that establish Jiang’s place in the history of xing-yi training manuals. First, he established the Shang Wu Jin De martial arts association in Shanghai. This association, partially financed by the government, was responsible for gathering together a number of hand-copied xing-yi texts as well as bringing together teachers from a number of different traditions to compare their techniques. Secondly, starting in 1932, Jiang worked in the publishing division of the government-financed Central Guoshu ("National Martial Arts") Institute, and as a result he was able to publish a variety of Chinese martial arts training texts during his tenure there. Finally, he was a prolific writer of martial arts texts. (Titles include Xing Yi Mother Fist, Xing Yi Eight Forms, Mixed Forms Fist, Xing Yi An Shen Pao, and Xing Yi Five Forms Linked Fist.) The first of these is the most comprehensive, while the latter three discuss specific xing-yi forms. Joseph Crandall has translated a number of these texts into English, and the translations feature the original photographs and line drawings of their respective books.

Li Tsun-I’s (1847-1921) contribution, Yueh Fei’s Intent Boxing, is what might be called a transitional work, as it blends the style of the hand-copied manuals with the how-to of the Republican period. The work was reputed to be the original text discovered by Ji Ji Ke and passed down in hand-copied versions to Li, who in turn dictated it to his student Dong Xiu Sheng (1882-1939). In 1934 Dong released the book in a public version. This public version included Li Tsun-I’s work along with supplemental material that expanded it to two volumes.

Another prominent author of this period was Huang Bo-nien (1880-1954). His book, Hsing-I Fist and Weapons Instruction, is interesting because it was the first xing-yi book written specifically for use by the military. Published in 1928, the book was authored by Huang with Jiang Rong-qiao posing for the photos. The government as part of their program to support Chinese martial arts both within the military as well as the general public underwrote publication of this volume. The book covers the basics of xing-yi’s five-element fist and a version of Linking Fist along with the basic training ideas of xing-yi.

Two things set this book apart. First are sections detailing the use of the bayonet and saber based on xing-yi principles and forms. Second, it is explicitly designed for use by the military. Thus in discussing each of the five-element fist methods, movements are broken down into the individual commands that a drill instructor would use in drilling a large group of soldiers.

Line drawing from Hwang’s Hsing-I Fist and Weapons Instruction, 1928

An English translation of this manual has been done by Chow Hon Huen, edited by Dennis Rovere. The translation, entitled Hsing-I Fist and Weapon Instruction, features the original line drawings but substitutes modern photos for Jiang Rong-qiao’s originals.

All of the above writers were from the Hupei-Shanxi tradition. The Henan tradition’s first book was Xing Yi Boxing Manual by Bao Ding (1865-1942), published in 1931. Part one describes the basic theory of Henan xing-yi and provides some stories of the masters of that tradition, while the second part features photos of Bao Ding performing the Four-Fists, Eight-Posture form.

Lesser books also appeared, but in general the text and photos of such

manuals tend to be similar to those listed here.

Modern Period

The modern period begins about 1950, and extends to the present. During this period, there are two major streams, the Nationalists on Taiwan and the Communists on the mainland.

At various times both the Nationalist government in Taiwan and the Communist government on the Mainland have given financial support and official approval to a variety of xing-yi training manuals. Additionally, private publishers in both Taiwan and Hong Kong have put out a wide range of xing-yi training manuals.

In most ways the modern period is simply a continuation of the Republican

period. That is, the training manuals have photos, footwork diagrams, and

textual explanations. Developments during the modern period include the

introduction of texts written in languages other than Chinese. For example,

the first English language book distributed in the United States that was

devoted entirely to xing-yi was Hsing-I Chinese Mind-Body Boxing

by Robert W. Smith. Published by Kodansha International in 1974, this book

is notable for two reasons. First, it featured photographs of several of

Taiwan’s best-known xing-yi practitioners of the late 1950’s and early

1960’s. Secondly, it includes quotes from a number of earlier Chinese language

xing-yi manuals. This book is out of print and should not be confused with

a newer xing-yi book by the same author. A second development of the modern

era is the advent of instruction via videotape and DVD. Finally, there

have been a number of books and articles describing xing-yi practitioners

in an anthropological context. Examples include Dru C. Gladney, Muslim

Chinese: Ethnic Nationalism in the People’s Republic of China (Cambridge,

MA: Council on East Asian Studies, Harvard University, 2nd edition, 1996).

What Xing-yi Manuals Contain

Disregarding the anthropological studies, xing-yi manuals of all eras are "all the same book," in the words of respected Taiwanese martial arts historian and publisher Lue Kang-I. To a large extent, that is true. Xing-yi manuals of the hand-copied period usually contained a fairly standardized list of mnemonic words that trigger by association the readers’ memory of various principles and techniques. For example there is the "Eight Set of Threes": 3 presses, 3 hooks, 3 rounds, 3 quicks, 3 embraces, 3 sinkings, 3 curves, and 3 stretches. When the reader-student saw these s/he knew, for example, the three sinkings meant "the qi [chi] must sink, the shoulders must sink and the elbows must sink."

Most hand copied manuals also contained "poems" for each of the fist forms. These poems were rhymed couplets, usually seven sets of two lines each, which in vague "poetic" form described key points of the fist form. As an example of this, the first two lines of the poem for Splitting Fist form (one of the Five Forms) reads: "Both fist, united, rise up to the mouth; fist rise to eyebrow level, fist drill." As both these examples make clear, unless one already knows xing-yi, these various formulas make little or no sense. Additionally, hand-copied texts frequently contain lineage lists, anecdotes of prior masters, and general training advice, and occasionally line drawings.

Page from Li Chunyi’s book Yue’s Intent Boxing (1934) showing Splitting Fist

Books of the Republican period included these same formulas, poems, and lineage lists, but added photographs and detailed discussions of how to perform the various xing-yi forms. Basically, hand-copied manuals were designed for students already familiar with the art, and so they emphasized key points and principles. In contrast, manuals of the Republican period were designed as do-it-yourself books. Now, it must be added that even during the Republican period, the books did not "directly tell all," so to speak. Each of the manuals of the Republican period will omit some key idea. For example, the "follow step," which is critical to xing-yi striking power, is often glossed over or not mentioned at all in Republican era manuals. Another common omission is failing to stress the importance of san ti training. Often referred to as "standing post" training, this consists of holding a static posture for various lengths of time. This training serves a number of purposes, and is discussed in detail in Michael W. Jones’ article "Standing Like a Stake: Internal Pathway to Power," in the June 2001 edition of Physical Training.

Modern books generally include mentions of such key ideas, but still

go on to say that nothing replaces tutelage under a good instructor.

Epilogue

Xing-yi practitioners are fortunate that their art has a long, documented history of training manuals, as it allows them to directly consider the words and see photographs of some of xing-yi’s finest historical practitioners. In this regard, the "secret training manuals" of popular novels and movies have been successfully guarded and passed down to future generations.

Bibliography

English-language Texts

Jiang, Rong-qiao. Hsingyi Mother Fist. Trans. Joseph Crandall. Pinole: Smiling Tiger Press, 1999.

Huang, Bo-nien. Hsing-I Fist and Weapon Instruction. Trans. Chow Hon Huen. Ed. Dennis Rovere. Calgary: Rovere Consultants International, 1992.

Li, Cunyi. Xingyi Connected Fist. Trans. Joseph Crandall. Pinole: Smiling Tiger Press, 1994.

Miller, Dan and Tim Cartmell. Xing Yi Nei Gong. Burbank: Unique Publications, 1999.

Pei, Xirong and Li, Ying’ang. Henan Orthodox Xingyi Quan. Trans. Joseph Crandall. Pinole: Smiling Tiger Press, 1994.

Smith, Robert W. Hsing-I Chinese Mind-Body Boxing. Tokyo: Kodansha, 1974.

Sun, Lu Tang. The Study of Form-Mind Boxing. Trans. Albert Liu.

Ed. Dan Miller. Pacific Grove: High View Publications, 1993.

Chinese-language Texts

Bao Ding. Xingyi Quanpu (Xing-yi Boxing Manual). Shanxi Science and Technology Press, 2000.

Jiang Rong-qiao. Xingyi Za Shi Chui (Xing-yi Mixed Strikes and Eight Posture Routines). Shanxi Science and Technology Press, 2000.

Li Chunyi. Yue Shi Yiquan Wuxing Jingyi (Yue’s Intent Boxing, Five Element Essentials). Ed. Dong Xiusheng. China, 1934.

Taigu County Gazetter Office. Xingyi Quanshu Daquan (Complete

Book of Xing-yi). Shanxi People’s Press, 1993.

Internet Resources

David DeVere’s Kong Hua Xingyiquan page, http://www.emptyflower.com/xingyiquan/index.html

Jarek’s Chinese Martial Arts page, http://homepages.msn.com/SpiritSt/xinyi/index.html

Joseph Crandall’s Smiling Tiger site, http://users2.ev1.net/~stma/

Tim Cartmell’s Shen Wu site, http://www.shenwu.com

The Wushu Centre site, http://www.thewushucentre.ca

About the Author

Brian Kennedy is an attorney living in Taiwan who teaches and writes

about criminal justice. He has studied a variety of Chinese martial arts

including hung gar and xing-yi.