Copyright William Baxter © 2002. All rights reserved.

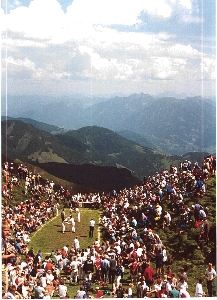

It was July 29th, St. Jacobís Day, and early in the morning on every side of the mountain long lines of pilgrims climbed steadily to the top of Hundstein. They came from every country in the Alps: Karentin, Salzburg, Tirol, Ost Tirol, Sud Tirol, Bavaria, and Switzerland. They could not afford to slow down, either, as Father Eichhorn intended to commence Mass at 10 a.m. in St. Mariaís Alm (meadow) and they had 2,116 metres to climb.

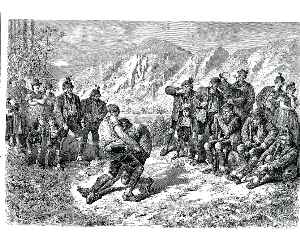

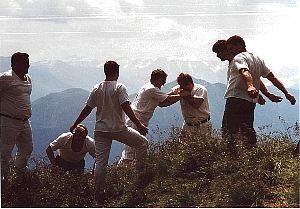

Nineteenth century image of Ranggeln

As the priest finished his sermon, the sun sparkled behind him on the great glacier far across the valley. This year there was no snow and in the bright sunshine an eagle, his solitude disturbed by the spectacle, soared overhead, the flight feathers of his great wings like fingers gripping the sky.

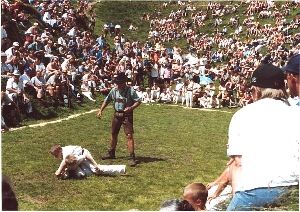

Once Mass had been celebrated, the real business of the day could begin and the young men of the mountains queued to enter the wrestling competition. They spoke a dozen different dialects of German, some almost incomprehensible to each other but they all had one aim before them, to be Hagmoar of Hundstein. These were no gymnasium athletes from the cities but the sturdy sons of the mountain peasant farmers: shepherds, herders, woodsmen and hunters. The haymaking was almost finished and they had energy to burn.

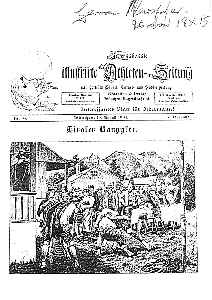

"Tiroler Ranggeler." The image depicts wrestling from about 1815.

From the German-language "Illustrated Athletic Newspaper," August 19, 1894.

Like churchmen everywhere in mediaeval Europe, Leonard of Gottsgnaden, Archbishop of Salzburg, was concerned about pagan survivals, and so on "Montag nach invocavit im Yar 1518" he considered whether to ban the custom which, "had existed since ancient times." Good sense had prevailed and the young men continued to wrestle. And so, at the end of a long dayís sport, a new Hagmoar was proclaimed and carried around the arena by his jubilant friends.

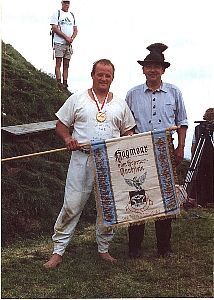

Surrounded by gnarled old men in lederhosen (leather trousers) and elaborately decorated hunterís hats, the Hagmoar, the champion, was presented with the traditional prize, a banner. And, as his friends and rivals slapped his back or shook his hand, a tall and beautiful black haired girl wearing the low cut dress of the mountains smiled at him amid the hubbub, then leaned over and spoke into the new championís ear: "Moment bitte, the reception has failed." When he realised what she had said, Helmut Kendler looked over at the TV crew and grinned sympathetically at their plight as yet another friend shook his hand.

The Invocation

The date was July 29, 2001, and the biggest change to Ranggeln since Albrecht Dürerís Fechtbuch was published in the Year of the Lord 1512 was the TV crew.

Ranggeln, the wrestling style that lends its name to a brand of jeans and to US cowboys, is the oldest sport in the European Alps. Rangglers have no mythology of ancient masters who meditate and preserve their secrets among the eternal snows. They spend their working lives there and for hundreds of years, (perhaps thousands, since man first arrived in the Alps) they have wrestled, and in Ranggeln only the best and toughest can win.

Just what is Ranggeln and why is it so culturally important?

Austria is where the Celtic Hallstat Iron Age culture began and it was at its peak around 700 BC. When the Greek heroes had fought before Troy one or two of the more fortunate ones possessed iron knives perhaps traded from their more technically advanced neighbours to the north. The slightly later Celtic La Tene culture spread from its heartland in the Alps and by 400 BC it was a cultural unit, which spread from modern Ankara in Turkey to the scattered Atlantic islands of Scotland and Ireland.

No one knows today just which God or Goddess the mountaineers of the Alps sought to propitiate when they first wrestled on Hundstein but the most likely is Lugh, the sun god. The feast of the sun god called Lughnasadh in Gaelic was one of the four major pre-Christian festivals of Europe and was basically an agrarian celebration of the harvesting of the crops. When Augustus Caesar chose Lugdunum (Lyons) as the capital of Roman Gaul he ordered that a festival be inaugurated in his honour. The celebrations were held on August 1st, and were obviously meant to identify Caesar with the ancient Celtic adoration of Lugas who had provided the people with food.

Christianity took over this festival as Lammas and the name survives in each of the Celtic languages; in Irish as Lúnasa (August), in Manx as Luanistyn (August), and in Scottish Gaelic as Lúnasad (for the Lammas festival). "Monuments and inscriptions to him are more common than for any other Celtic god and it is generally accepted that when Caesar spoke of the Gaulish "Mercury" he was speaking of Lugas." (Berresford Ellis) The name appears in many European countries as the cities of Lyon, Leon, Loudan, and Laon in France, Leon in Spain, Leyden in The Netherlands, Leignitz in Silesia, and Carlisle (Lugovalum in Roman times) in England. London is thought be derived from Lugdunum, hence the Latin Londinium.

The new priesthood systematically denigrated the old gods and took over their holy places as Christian sites with Christianised names. However, a powerful god like Lugh, the patron of all the arts and crafts, was never eradicated. He gradually became diminished in peopleís minds over many generations as a fairy craftsman named Lugh-chromain (stooping Lugh). "Now all that is left of the potent patron of the arts and crafts is the Anglicised version of Lugh-chromain, leprechaun". Berresford Ellis)

Perhaps even "Otzi," the man who was murdered 5,300 years ago on a nearby glacier and whose body and bronze and stone weapons were found several years ago, had wrestled at Hundstein. What is certain is that a 400 BC bronze La Tene scabbard for an iron sword, found in Hallstat about 70 kilometres away, illustrates a type of wrestling which just possibly might be a remote ancestor of modern Ranggeln. Anyway, there are four panels on the scabbard and the one at its point shows two wrestlers on the ground. "The decorated bronze sheath for an iron sword found at Hallstatt shows how much we can learn about a people who illustrate their own daily life. These military scenes depict wrestling (far left), foot soldiers and cavalrymen with typical weapons and gear, flanked by men who hold the circular symbol of warfare. The fourth century BC sheath is about 70 centimetres (28 inches) long." (Cunliffe)

When the Germanic tribes first moved into the mountains about 100 BC, they mingled with the indigenous inhabitants who had remained and continued the custom of wrestling on Hundstein. Possibly they even commenced it. Ranggeln is free style wrestling and is technically the same sport that is practised in the Olympic Games or US colleges. The differences in the rules are slight: as in Asian kushti/gures holds can be taken on the clothes and rangglers wear a tough canvas shirt and cotton trousers, which make spectacular throws easier.

Prior to World War II, challenge matches were held among the mountaineers when they met at markets or at traditional meeting places in the high Alps. There were slight rule variations from district to district, such as the variation called Hosenlupfen, or trouser wrestling. However, the rules were standardised when the Salzburger Rangglerverband was formed in 1947. Modern Ranggeln bouts last 6 minutes. There are no points, only a fall counts and a rolling fall or to bridge is counted as a fall. Submission holds and strangles are forbidden and there are no draws; a drawn bout eliminates both competitors. Therefore bouts are fast and furious since the wrestlers must gain a pin to survive into the next round.

For Further Reading

Text

Hagmoar vom Hundstoa by K Nusko published in Salzburg in 1972

Das Ranggeln im Pinzgau by Ilka Peter, published by Verlag der Salzburger Druckerei, 1981

The Celtic World by Barry Cunliffe, published by BCA and Constable and Co. Ltd., London, New York, Sydney, Toronto 1992

Dictionary of Celtic Mythology by Peter Berresford Ellis, published

by Constable and Co. Ltd, London 1992

Online