Copyright © EJMAS 2004. All rights reserved.

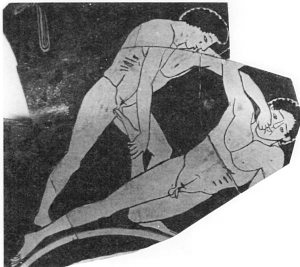

Fig.1. Pottery painting attributed to Onesimos, c. 500 BCE. (From Michael B. Poliakiff, Combat Sports in the Ancient World, illustration no. 14, p. 30. Copyright 1987 by Yale University Press; used with permission.)

Shown in Fig. 1 is a pottery painting dating from ca. 500 BCE and attributed to Onesimos. It depicts two combatants, one standing, one recumbent, who will henceforth respectively be referred to as the "up man" and the "down man." The down man is propping himself up on his side with his left arm and reaching up with his right arm; his left leg is bent back at the knee. The up man is crouching over the down man, grasping the latterís left ankle with his right hand, his closed or partially closed left hand engaging the down manís face. The up manís right side and the down manís left side each bear a distinctive pattern of striations oriented in mirror-image fashion.

The painting, part of a private collection, became widely known when Michael B. Poliakoff included a photo of it in his Combat Sports in the Ancient World. Poliakoff takes the scene as a wrestling match in which "offense attempts to turn the opponent to his back by pulling the leg and wrenching the face." Commenting on the striations, he adds, "The bloody imprint of a hand appears on each athlete." (p. 30)

Based on an analysis of the striations identified as bloody handprints, this article will make a case that the contest is not wrestling, but rather pankration. Having made the case for the latter, the article will then offer an alternative explanation of the description of the action as a wrestler attempting to turn his opponent on his back for a fall.

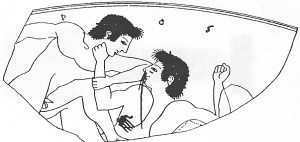

The problem with the identification of the striations as bloody handprints becomes evident when Fig. 1 is compared with Fig. 2, which unambiguously shows a bloody handprint on the combatant on the right. The handprint includes a distinct palm impression, and the combatant on whose body the print appears has a copious discharge of blood from the nose. In Fig. 1 the putative handprints lack palm impressions, and neither combatant appears to be badly bloodied.

Fig. 2. Line drawing of pottery painting from late 6th century BCE. (From E. Norman Gardiner, Athletics of the Ancient World (1930), figure 190, p. 215. By permission of Oxford University Press.)

If the marks are not handprints, what else could they be? During the wrestling match between Odysseus and Ajax at the funeral games for Patroclus, bloody weals appeared on the ribs of the combatants (Iliad 23. 700-735). Although this is an attractive explanation, and one that could be marshaled to preserve the interpretation of the painting as depicting wrestling, there is better explanation that points to pankration as the sport depicted.

Shown in Fig. 3 is a video still from the Don Frye / Mark Hall quarterfinal bout of UFC 10 fought in Birmingham, Alabama on July 12, 1996. Frye took Hall down early on, and Hall defended on his back from what is known as the guard position, wrapping his legs around Fryeís waist and wrapping his arms around Fryeís neck to cinch him in close. Unable to sit up in Hallís guard and deliver punches to Hallís face, Frye instead pummeled his left side with a barrage of short, choppy rights. A pattern of striated welts began to appear on Hallís side in the same position and alignment as the marks on the down manís side.

Fig. 3. Don Frye (top) vs. Mark Hall in UFC 10. (Original UFC 10 video copyright 1997 by Semaphore Entertainment Group; video still reproduction permission courtesy of Joshua Hedges, Zuffa LLC.)

This suggests that the down man had been in the same predicament as Hall, defending from the guard position while the up man threw short, choppy rights at his left side. But since the up man has mirror-image marks on his right side, it would appear that he too had been in the same predicament himself, except that he had been struck with short, choppy lefts (probably indicating that the down man was a left hander). Since each man had apparently taken turns being pummeled while defending from the guard position, thereís no way the contest could be a wrestling match; it would have to be pankration.

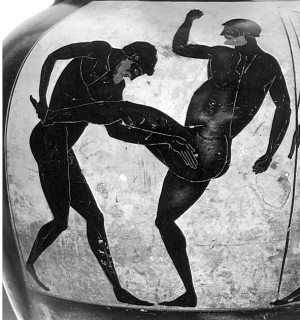

Another indicator that the contest is pankration comes from a reconstruction of how the combatants came to assume the positions shown in Fig. 1. Shown in Fig. 4 is a pankratiast with clenched fists throwing a kick with his left leg; his opponent has seized the ankle of the kicking leg with his right hand and lifts the leg with his left arm to topple the kicker over backwards. One way in which the pankratiast throwing the kick could attempt to extricate his seized leg would be to spin to his right. If unable to kick and twist himself free, he could be upended onto the ground, landing in the same position as the down man. Rather than depicting a wrestler attempting to turn his opponent on his back for a fall, Fig. 1 more than likely illustrates the aftermath of what is shown in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Pottery painting attributed to the Kleophrades Painter, ca. 500-490 BCE. (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1916. [16. 71]. All rights reserved, The Metropolitan Museum of Art (NYC); used with permission.)