Copyright © EJMAS 2004. All rights reserved.

Introduction

By means of his groundbreaking essay "African Roots in Asian Martial Arts" (Journal of African Civilizations, 7, 1: 138-143), his two-part video (The World of African Marital Arts, CFW Enterprises, 2000), his television appearances ("Strange Universe," "Masters of the Martial Arts"), and his teaching (at the Ta-Merrian Institute in Detroit, Michigan and at seminars internationally), Kilindi Iyi has become an important North American spokesperson for the African martial arts.

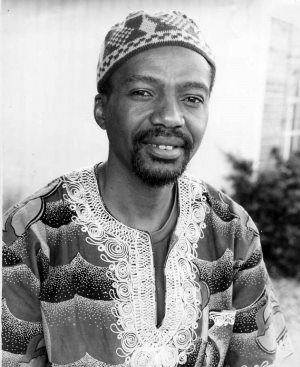

Kilindi Iyi, 2004

Beginning with the rise of African consciousness among African-Americans in the late 1960s, Iyiís attempts to re-connect with what he prefers to call African martial sciences have led him to explore not only fighting systems, but also dance, music, philosophy, and ethno-medicine. His work has generated both controversy and a dedicated following.

The following is a portion of an interview conducted in 2004, during his stay as guest lecturer and visiting artist at Texas A&M University. In it, Ahati (a Kemetic title used by his students meaning, "He who strikes with the powers of the deity") Iyi deals with two issues: the sources of his knowledge of African martial systems and his projections for the future of their study.

***

Green: Would you begin by telling us how you were introduced to martial arts?

Iyi: I started out with boxing. My father taught me boxing as

a young boy, because he was a professional boxer. Basically, his most productive

years of his boxing career were short-circuited by World War II, where

he was stationed in the Philippines. He came back from World War II and

married my mother, and he still had the fever of wanting to continue his

career. With a family, it really wasnít feasible to do anything like that,

so he got into coaching, and I learned boxing from him. My mother didnít

particularly care for the boxing as far as me going into professional boxing,

or going into Golden Gloves and tournaments. I did sneak over to the recreation

center and places like that anyway.

A Lansing, Michigan, boxing card featuring Kilindi Iyi's father,

Jimmy Johnson

Then, around 1965, I went to the Michigan State Fairgrounds and saw judo demonstrations and karate, aikido, and taekwondo demonstrations, and I was fascinated by that. I wanted to learn when I saw that at the State fairground. As far as learning was concerned, money being scarce, my father wasnít going to pay money for martial arts lessons. "You know how to box, and I taught you how to box."

So I had to buy books and read Black Belt Magazine and things like that until the day I got the chance to train. My first instructor was a man by the name of Woods who had learned in the Army. I trained with him and other people around the neighborhood [in Detroit]. I eventually got a chance to train in a little bit of karate and a little bit of this and a little of that.

By that time, it was getting to be the late Ď60s, Ď68 or Ď69, and black consciousness was on the forefront of the American scene. It became a focus of identity on Africa: "Black is beautiful," "Black Power," and things like that. And I got involved in that. I had begun to get involved in the martial arts and learn Asian martial arts, and thought, "If all people around the world have martial arts, well, Africans must have martial arts, also."

So I began to do as much research as I could. I really couldnít find anything. I would talk to people, and then I said, "Well, maybe some of the African students from different colleges might know something." If so, I could ask them when Iíd see them on the campuses of the University of Detroit or Wayne State University or the University of Michigan or Michigan State.

I started asking African students about martial arts, "Do you know anything about martial arts?" And theyíd say no. And in truth, they were telling the truth. Because there wasnít anything called African martial arts, but the Africans did have their systems of warfare and fighting and wrestling, punching systems and systems of weaponry, and I began to discover things like that. So, once I got to the knowledge base of being able to ask in a proper way, I started getting responses.

We had several people in town who were Africans, who guided me in certain directions. There was a brother from Zululand named Zukele who had a South African restaurant in Detroit called Fechu. I learned Zulu stick fighting and martial art from him. There was Mr. Kupalui who had an African shop in Detroit who would tell me about different things. Meeting the students and talking to people led me to other ways to do research into African martial arts.

Once I started studying and researching in the early Ď70s, I started

to go to New York to do research at the Schomburg library. The Schomburg

collection is the largest repository of African and African-American history

in the country. (EN1) In New York, I would research

there on the African martial arts, and I started meeting people. One of

the greatest influences was Baba Ishangi, the head of the Ishangi

Family Dancers, who had basically came to the forefront in African culture

at the Guinea Pavilion at the 1965 Worldís Fair in Queens, New York. I

met him in the mid-70s, and followed him for several years. (EN2)

In fact, he introduced me to other people -- Nana C.K. Ganyo (EN3),

Dr. Hodari Mqulu (EN4), and others who were instrumental

in developing my African sensibilities and of being able to understand

the gist of African arts.

Hodari Mqulu, an isangoma (healer/diviner) from South Africa

who was instrumental in Kilindi Iyi's training.

I eventually trained in Naboot (EN5) with a brother by the name of Mohammad. I hooked up with his uncle in Egypt later on in the late Ď70s, who was also named Mohammad, who I continued my study of Naboot with, and I was just training and learning and getting the chance to visit Africa. I based myself with West African tribes, to try to understand the arts based in Senegal and Ghana and The Gambia. Although Iíve never been to Nigeria, I had people from Nigeria who taught me Nigerian martial arts. Baba Adeboye was one of the people who was advising me on Nigerian martial arts. He lived in the Nigeria. He was the son of a paramount chief there. He learned things from warriors under his father from all the different Yoruba societies. Things like that are part of my learning experience

So thatís basically the background on how I started and the people I got with to learn a lot of the things I do. I donít stick really to one system. I blend the systems from Africa and from different people, because I think, in my studies, theyíre one. Theyíve just been dispersed, and there are certain areas that have preserved more than others. So I blend the arts of Africa rather than sticking to one particular mode such as the Akan, the Yoruba or Hausa, or the Mende. I blend them all together. I see them as one and thatís my own personal viewpoint as far as the martial arts of Africa.

Green: So thatís why you chose the name Ta-Merrian rather than African?

Iyi: Well, the Ta-Merrian Institute, thatís just the name

of our school. Itís not the name of any art or anything like that. Thatís

the name of our building, and we gave it that name out of respect to the

old empire -- Ta-Merri. Ta-Merri actually means "the loving earth" or "that

which sustains and protects us." So the Ta-Merrian Institute or the Ta-Merrian

Institute per Ansar; Ansar is "the house of resurrection." So itís actually

the house of the resurrection of the knowledge of the ancestors.

Ta-Merrian students training in Ghana during 2001

The institute deals with many different areas of African knowledge. Martial arts was one of them. And many people have taken that wrong, because I get called on that quite a bit and they say, "Well, thereís no such thing as Ta-Merrian martial arts." And, of course, if you understand, like my group understands and people who know who look at history know, that thereís no martial art in Africa called Ta-Merrian martial arts. But they [detractors] donít know thatís just the name of our building. The institute itself.

Green: What is your view of the future of African martial arts?

Iyi: My vision for African martial arts is to make it a viable part of the African American scene and the general martial arts population scene, so that it brings martial pride and a better understanding of culture all the way around. In viewing Africa as something that is positive and that has given a positive contribution.

So my vision of where African martial arts is going? I see it coming into the mainstream of the martial arts community very soon, as soon as we can get certain aspects of it to a point where itís viable. People are seeing the same growing pains that the Asian martial arts had in the Ď50s when they were just coming out.

Originally, you didnít really have a way of teaching Asian martial arts to Westerners. The curriculum of the martial arts world came out of judo, out of Jigoro Kanoís way of trying to put the thing together. And he used a lot of Western influences inside of doing that, because in martial arts, even when [U.S.] soldiers brought back karate and things like that from Japan and Okinawa after WWII, they didnít have a way of teaching it either. Thatís why you have the jumping jacks and the pushups and the things like that for conditioning. Thatís not how martial artists taught. Your lifestyle gives you strength and exercise.

Weíre about to go through the same type of problems with promoting African

martial arts as Dan Inosanto did [with Filipino martial arts]. He had difficulty

when he was first bringing out kali. When heíd try to promote it,

people said, "Oh, heís taken things from aikido and heís taken things from

this and heís taken things from that and put it into kali to make

it more viable." And later you find out kali had all these things.

It has the outward wrist press and all the type of things you see in other

arts. Then he had problems with the Filipinos who were native-born Filipinos

on the island because he was born in California. [They believed h]e didnít

really know anything because he didnít live in the Philippines. Heíd never

been to the Philippines, and then he couldnít even go to the Philippines,

because if he goes to the Philippines those people there would try to challenge

him and cut him up.

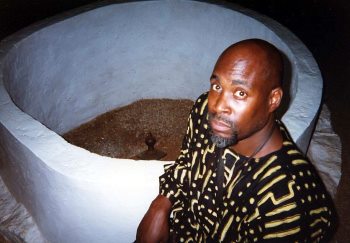

Kilindi Iyi at the site in Kumasi, Ghana, where Okomfo Anokye, a

leader of Asante (Ashanti) unity during the 1700s, reportedly drove his

sword into the ground with such force that it subsequently became immovable.

African martial arts are just coming into that point, where the controversy of whoís legitimate and whoís not legitimate and what styles are real and what styles arenít real [has emerged]. All these lineages and whoís this teacher and whoís that teacher and all these things come into play. And the worst part of any art in our time is coming out in a society that is no longer hand-to-hand combat martial. Itís just the flavor of what things were in the olden days. And in the olden days, the proof was in the pudding. It wasnít in the talking or the writing on the Internet. It was in what you can do, and thatís how it still is in Africa.

I go to Africa and I say Iím a stick fighter, and they say, "Well, okay, get you a stick and letís see." And when you stick fight with them, they say, "Okay, show us what you know and weíll show you what we know." Itís not a thing where you say," Iím a stick fighter," and they say, "Sit down and letís have some coffee." Weíre talking about street fighting. And you say youíre a wrestler or you say youíre a fighter. "All right, come on out and show us what you got." And if they like it, they say "Fine," and if they donít like it they say, "Well, you ainít that good." They donít play and mince words and do this whole armchair warrior type of thing.

So African martial arts are starting to go through growing pains. I donít have any problems with what they say about me because I have luckily documented my teachers, and many of the things Iíve talked about with you I can show in those old [film] clips where I get the things that I do. Like I said last night [after a lecture at Texas A&M], the guy who had studied arnis, he didnít look at the clip. He just looked at Kenny [a senior student who demonstrated African stick fighting], and he said, "Well, thatís arnis," and I said, "You didnít look at the clip."

That movie had nothing to do with arnis, with kali, or the Philippine Islands, or any of that. It was an indigenous African dance to Ogun (EN6) with a machete that could be translated into stick fighting. The spinning of the stick, the spinning of the sword, they learned those things as children which I showed in the clip of the little boy at the initiation. He wasnít in his initiation, but he had on his initiation clothes, the costume that they utilize when they go out for initiation. They had to show what theyíre learning out there [during initiation]. And this is one of the dances theyíd do in front of their elders. That was footage we took right outside of the village that we go to [in the Gambia]. And thatís what the young boys do. You could get up in the morning and see the masquerade[r] that takes the young boys to the bush, coming down the road with machetes. Heís in all black, and he has two machetes, and heís running down the road, and all the young boys are running away from him because they know when their time comes theyíre going to be snatched out to that bush.

It [martial practice] is still real [in African village contexts]. Itís

not the kind of thing where you go and pay money at the school. Youíre

a young boy, and youíve been given all the areas of what you need to survive.

And when you go out there you need to step up and aspire to learning what

you need to know to come back to being a man in that community. But the

thing is, you already know those things. Because youíve observed them,

and youíve participated in them, and youíve done the things that are necessary,

because they donít take folks out who arenít ready. If youíre in the society,

youíre ready because the people in your family have the responsibility

to have you ready when that masquerade runs down the road.

Lamin Sonko teaching a class in Ghana, 2003.

Well, weíre building a curriculum teaching method that best serves Western aesthetics. Because youíre not going to go to the village and live there. Thatís the only way you can learn anything natural. In the African martial arts, weíre taking an ancient martial arts core thatís not really suited for modern living and trying to put it into a modern academy. If youíre going to learn it three times a week for $60 a month, it has to be a different type of curriculum to be palatable to the practitioner here. So those things are being developed over here to try to get the flavor of how the training was, a curriculum that will give you the flavor of what was in the traditional sense, but will still be something that people can deal with and still be able to go home and kiss the wife.

So, African martial arts are having growing pains, but I think thatís

good because it clears the air from the beginning and leaves room for growth.

About the Interviewer

Thomas A. Green is an associate professor in anthropology at Texas A&M.

His recent books include Martial Arts of the World: An Encyclopedia

(ABC-CLIO, 2001) and Martial Arts in the Modern World (Greenwood,

2003).

Endnotes

EN1. The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture link is part of the New York Public Library system. Its web site is http://www.nypl.org/research/sc/sc.html

EN2. Baba Ishangi (d. 2003) was in Detroit in 1975, at the International Theater Olympiad (http://wwwtheatertrips.org/ish-history.html). This is likely the occasion of their first meeting. For an obituary and brief biography, see http://www.ishangi.com/announce.html

EN3. Cornelius Kweyku Ganyo (d. 2003) was Ewe, from Ghana. He played bembe and djembe drums, backed Charlie Parker, the Grateful Dead, and Fleetwood Mac, and taught classes at Arizona State. For an obituary, see www.ccdr.org/Newletters/issue23-2003-dec.pdf

EN4. For a brief discussion of the powers and role of the isangoma in Nguni life, see http://izmo.tripod.com/project/zulu.htm and http://bbg.org.za/tradheal.htm; for a discussion of an isangoma's specific involvement in Nguni stick fighting, see http://ejmas.com/jalt/jaltart_Coetzee_0902.htm

EN5. Naboot is the long staff used in the Egyptian art of tahtib. Peter Kautz mentions tahtib at http://www.alliancemartialarts.com/tahtib.html, and according to dance scholar and filmmaker Magda Saleh in a 1980 interview, it is the oldest form of Egyptian martial art to have survived, reasonably intact, from remote antiquity. See http://eres.geneseo.edu/farrellk/web/record.asp?id=110

EN6. In Robert Farris Thompsonís description, Ogun, the warrior orisha (Ďdeityí) of the West African Yoruba, "lives in the flames of the blacksmithís forge, on the battlefield, andÖ on the cutting edge of iron" (Flash of the Spirit. New York: Vintage, 1984, 52). Transplanted to the New World during the African Diaspora, Ogun has since been reinterpreted in various American contexts.