SDKsupplies

THE OMORI RYU

The first techniques that a student of Iaido must learn in either the Muso Jikiden Eishin Ryu or in the Muso Shinden Ryu are the Shoden waza. These are usually introduced as the Omori Ryu which invariably causes confusion; is it a set in the main school or is it a separate school in itself. As will be mentioned, it is both.

Since these kata are the first and quite often the only introduction people have to Iaido they have a great influence on what is thought of the art. Due to their unique nature they have perhaps given the art of Iai-do a rather undeserved reputation. They have also influenced what type of student continues on in the art. When asked why they did not return after the first couple of classes, most people will say that they liked it but they didn't like all the kneeling. Does this mean that beginners should start with standing techniques? Perhaps, if one is seeking lots of students but it can be argued that this would do them no favours.

OMORI RYU HISTORY

The history of the Omori Ryu is linked with that of several schools including the Muso Ryu so the proper starting place is difficult to find. We will begin with the Muso Shinden/Jikiden line. The man credited with the origination of Iaido is Jinsuke Shigenobu (Hayashizuki) who lived around 1546-1621. He was thought to have been born in Sagami (Shoshu) and to have travelled to Mutsu where he studied the sword from 1596 to 1601. The sword drawing art he founded between 1601 and 1615 is usually termed Batto Jutsu. In 1616 he went on his second Musa Shugyo (dojo tour) at the age of 73 and never returned.

Shigenobu has been given the title of first headmaster of the Muso Jikiden\Shinden school. From his teachings several hundred schools of Iai were developed, of which some 20 to 30 are still extant.

One of the names for Shigenobu's art is the Muso Ryu, "muso" here means dream or vision, reflecting the way in which he was inspired to create the techniques. The second headmaster was Tamiya Taira no Hyoe Narimasa, the founder of the Tamiya Ryu. Tamiya was an instructor to Ieyasu (1542-1616), Hidetada (1578-1632) and Iemitsu (1604-1651) the first three Tokugawa Shogun.

The seventh headmaster of the Muso Jikiden\Shinden line was a man named Hasagawa Chikaranosuke Eishin (b. approx. 1700). He studied under the sixth headmaster, Nobusada Danuemon no Jo Banno (Manno Danueimon Nobumasa) in Edo during the Kyoho era (1716-1735).

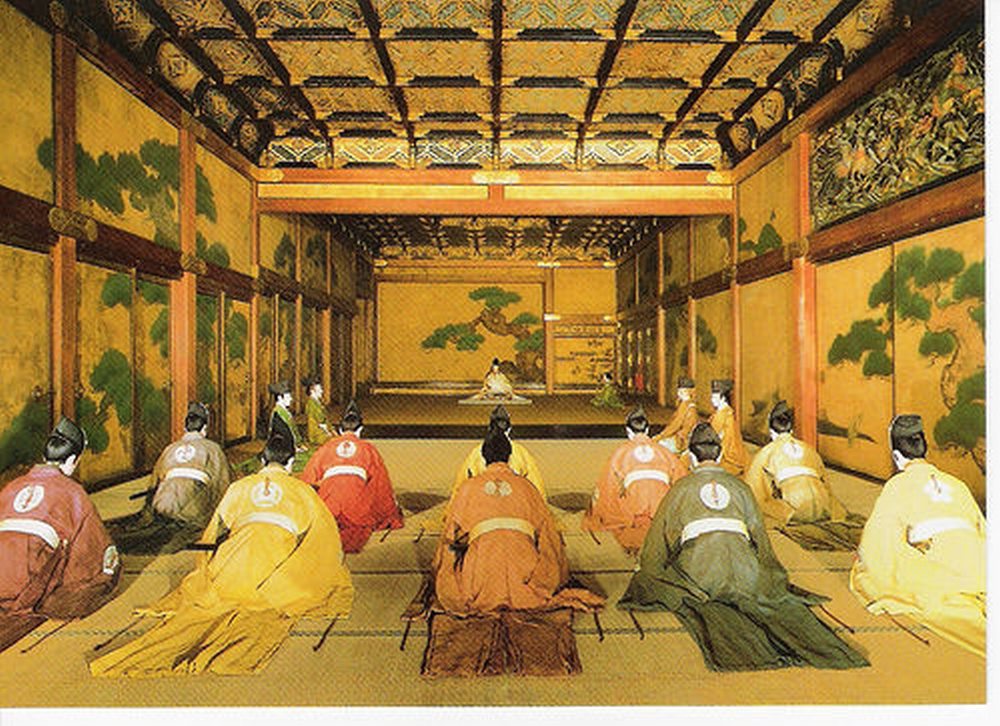

Eishin transformed many of the techniques and is said to have devised the style of drawing with the blade edge up in the obi. He added the Iai hiza techniques (Chudan level) to the Okuden levels of waza. It was Eishin who first used the name Muso Jikiden which had been the name of an earlier school of swordsmanship. The full name of the school came to be the Muso Jikiden Eishin Ryu. In this case "muso" means matchless or unique. "jikiden" means transmitted directly, as from teacher to pupil. Eishin eventually left Edo and travelled to Tosa (Koshi) in Shikoku. Omori Rokurozaemon Masamitsu was a student of Eishin and was expelled from the Ryu at one time for personal reasons. Omori was a student of Ogasawara Ryu Reishiki or etiquette as well as the Yagyu Shinkage Ryu (Bishu) school of sword. The Yagyu Shinkage Ryu had a set of five Iai techniques called the Saya-no-uchi Batto Gohan. Rokurozaemon developed a set of eleven Iai techniques which were initiated from the formal seated posture called Seiza. For this innovation Eishin re-admitted him to the school.

Hayashi Rokudayu Morimasa (1661-1732) the ninth headmaster of Muso Ryu was a cook and pack horse driver for Yamanouchi Toyomasa, one of the daimyo at Edo. Hayashi studied Shinkage Itto Ryu (of the Mito Han) in Edo. He was also a student of Arai Setatsu Kiyonobu the eighth headmaster of what was named the Shinmei Muso Ryu at that time (Muso Shinden/Jikiden Ryu). Hayashi also studied Shinkage Ryu kenjutsu with Omori Masamitsu. When he became the ninth headmaster of the Muso Ryu he began to teach the Omori seiza Iai as the Shoden Omori Ryu. Up to this point the Muso Ryu only contained techniques which began from Iai-hiza (Kiza, one knee raised) and Tachi Ai (standing). This seiza set became the initiation to Iaido, "shoden" being broken down to "Sho", beginning and "den", initiation. Hayashi eventually returned to his home in Tosa, finally establishing the Muso Ryu in Shikoku.

Hayashi Morimasa taught Hayashi Yasudayu Seisho (Masataka) who became the tenth headmaster.

In turn, Hayashi Masataka taught Oguro Motoemon Kiyokatsu who became the eleventh headmaster. Oguro also studied the sword under Omori Masamitsu. Thus we can see that although Omori was never a headmaster of the Muso Ryu, he had a direct influence on the school, being an instructor to at least 2 headmasters. This relationship of Omori to Muso Ryu is shown in the chart below.

In the Taisho era (1912-1926) the 17th headmaster (Tanimura Ha), Oe Masamichi (Shikei) (1852-1927) reorganized the school and officially incorporated the Omori Ryu Iai waza as the Shoden level. Shikei is the man who named the school the Muso Jikiden Eishin Ryu and set its present three level system.

At the time of the 11th headmaster the school split into two lines, the Shimomura and the Tanimura. The Tanimura line became associated with the "common" folk, or the Goshi farmer/warriors while the Shimomura stayed closer to the Samurai classes. Both lines were still quite secretive about their teachings when a Kendo expert named Nakayama Hakudo (1869-1958) studied under teachers from the two branches. Nakayama developed a style of Iai which has become known as the Muso Shinden Ryu and which is centred around Tokyo. It is Nakayama who popularized the name Iaido which appeared in 1932. The Muso Jikiden Ryu has since become more open and remains situated mainly in the West and South of Japan. The "muso" in Muso Shinden means vision as it did in the original Muso Ryu of Shigenobu. These two contemporaries, Oe Masamichi and Nakayama Hakudo are largely responsible for the modern survival and growth of Iaido. The two schools teach similar techniques, the katas differing in interpretation more than in fundamentals. The Muso Jikiden Eishin Ryu has 11 Omori Ryu techniques while the Muso Shinden Ryu has added one more for a total of twelve. The names used for the individual waza are different for each school. At the Chuden and Okuden levels of training both the names and the numbers of techniques are the same.

OTHER SCHOOLS DERIVED FROM OMORI RYU

The influence of the Omori Ryu was not confined to the Muso Ryu lineage, it also played a somewhat paradoxical role in the emergence of some modern Iai-jutsu schools.

TOYAMA RYU

In 1873 the Rikugun Toyama Gakko was set up as an army training school. The school included instruction in the sword and in 1925 the Toyama Ryu Gunto Soho was defined. The gunto being the later army sword that was of katana design and mounted somewhat like the old tachi, suspended from the belt instead of tucked through an obi. Teaching at the Toyama Gakko were Kenshi skilled in the Omori Ryu. These instructors developed a set of seven Iaido techniques for the gunto which were performed from the standing position.

NAKAMURA RYU

Nakamura Taisaburo (b.1911) studied the Toyama Ryu Gunto Soho and is one of the leading authorities on the school. He has gone on to create the Nakamura Ryu and has defined Batto Jutsu as the essential element. Nakamura has eliminated the seiza position saying that it is not practical. He has also stressed the importance of tameshigiri practice. From the standing Iaido of Hasagawa Eishin to the origin of Omori Ryu as a school incorporating seiza and reishiki, to the modern Iaijutsu of Nakamura which rejects the seiza position we have come full circle.

MODERN OMORI RYU PRACTICE

The Omori Ryu as it is practiced in the Muso Ryu is a highly formal set practiced for the most part from seiza. Great stress is placed on precise physical and mental form. The set is as much about reishiki as it is about Iaido, but since budo begins and ends with reishiki, this is probably not a problem.

But why learn Omori first, what was the reasoning behind this choice instead of, say, a set of standing techniques. After all the standing techniques are easier to learn, and they are "practical". Anyone seeing them would not be tempted to say that Iai-do was less "combat real" than Iai-jutsu. It probably isn't hard to reason why the Iai-hiza position is not used as the starting point. The pains in the left leg would just about guarantee that nobody would learn the proper techniques simply because of the distraction. What should probably be resisted however, is the temptation to say that since the Japanese student was used to sitting in seiza, it was a good starting point because it was familiar. Standing is even more familiar, and the position from which the sword is most likely to be drawn. Even if we accept Omori as the starting position, why would Nakayama Hakudo and Oe Masamichi then choose Iai-hiza techniques for the chuden waza. The very last techniques we learn are the easiest.

Are they the easiest though? Surely the headmasters of the Muso Ryu from Hayashi Morimasa onward had some reason for making Omori Ryu the shoden level. Lets assume they knew better than we and try to find some reasons.

The most striking (ha ha) thing about Omori is that a lot of the cuts are done from a kneeling position. This is handy because it doesn't allow the student to swing too far before the blade hits the floor. It removes the need to teach the student not to finish the cuts too low. Without being shown or told, the student discovers shibori and te-no-uchi, or at least discovers the need for them.

Kneeling also removes three out of seven joints from consideration while learning how to cut. This wisdom of this becomes apparent when you try to teach a beginner how to cut from a standing position. Tell a beginner to make a big cut keeping the hips low and the back straight. It won't happen. Now put the student on one knee and just ask for a big cut. The hips stay down since the toes, ankles and knees are not available to push them up. The back stays straight since if it moves the kneecap is likely to grind around on the floor. The hips stay square to the cut for the same reason. The student has only the shoulders and arms to swing with allowing you to concentrate on them.

The seiza position itself is useful. The saya must be properly controlled or it hits the floor. The back can be kept straight since only one joint (hip) is involved in letting it bend. Nuki tsuke is simplified with only one possible orientation of the hips (forward). Spiritually, the student begins and finishes in the most humble possible position, one that is close to the floor. The positon is vulnerable to attack and therefore can't be aggressive as can kiza or tachi ai. Moving up to a standing position from seiza requires great leg strength, giving the student a good root into the ground. Sitting solidly in seiza allows the student to know what that root should feel like while standing.

The list of benefits is long, think about all the instruction you have ever received in Iai, almost all of it can be examined in the Omori Ryu.

Omori is shoden, it is the teaching set. It is the place where we learn to walk, later we run. Counting the partner practices, the Muso Jikiden Ryu contains somewhere around 60 kata in total. The average person could probably memorize that many movements in a month so the object of Iaido must not be how many techniques we can memorize. The point is to perform one technique perfectly at the proper moment. For that you need only one technique but you need to be able to do it properly. The arguement is the old one of quality vs. quantity. To do Iaido you must know how to cut, Omori Ryu teaches you. To do Iaido you must know how to carry your sword, Omori Ryu teaches you. Patience, perseverance, perspective, perception, perspiration and all the other P words of practice (yes, even pain) are taught in Omori Ryu. It is shoden, as important as your first breath of air.

Malcolm Shewan, in his book on Muso Shinden Omori describes the kata as idealized and often impractical movements which are not meant to be battlefield maneuvers. Instead they are a matrix within which we can re-live the experience of the man who created the kata. Omori is a complete set and we should look at it as such, seeing the underlying principles of the whole. The set is not "beginner's stuff", if we could perform a perfect Mae (Shohatto) we would achieve the perfection of Iai.

THE OBJECTIONS TO IAI-DO AND THE RELATIONSHIP TO IAI-JUTSU

As was mentioned earlier, the fact that Muso Ryu begins with Shoden Omori has often created the impression that Iai-do is something overly concerned with form and etiquette, having nothing to do with "real" Iai-jutsu. This is rather like watching someone hit a tennis ball against a wall and then saying the game is silly since the wall doesn't hit the ball back. Some of the comments on Iaido published over the last few years are informative.

Otake Ritsuke describes modern Iaido as being too fast on the noto, this is an affectation for show only and is dangerous. Iaijutsu instead emphasizes a fast draw and cut (haya waza) which is more realistic and practical.

Omori Ryu has a slow noto, but also a slow nuki tsuke. Both are slow to teach proper form. Chuden and Okuden contain haya nuki, fast draws, but even here, fast is not attempted until the draw is smooth.

Nakamura Taisaburo has several comments on Iai-do, claiming it is not practical or realistic. The comments are found in Draeger's Martial Arts and Ways of Japan.

1. Seiza was not a position the classical warrior would adopt, it cannot be done with the daisho (two swords).

The classical warrior was as likely to be wearing a tachi and a tanto as the daisho which was not popular until the Edo period. The shin-to or katana was not introduced until the middle 1500s and the matched daisho style was developed much later. The very warriors that would have carried and used the daisho, the Tokugawa era samurai, were those who developed and adopted the Omori Ryu. The upper levels of Muso Ryu Iaido begin from the "battlefield" positions.

2. The nuki tsuke of Iai-do is too slow, it exposes a suki (opening).

This is doubtless true for the beginner practicing Omori Ryu, but a beginner is almost by definition exposing suki most of the time. This would not change whether a slow or a fast nuki was being attempted. For the expert the draw can be slow or fast, the opening will not be there. As with most martial endeavors, speed is not as important is proper timing. If speed were all that was needed the heavyweight boxing crown would be held by a flyweight. The nuki tsuke of the Muso Ryu can be very fast in the upper levels of practice.

3. The kiri tsuke of the Iai-do student is weak since they lack experience with tameshi-giri (cutting practice).

To be flippant, there is no law that prohibits Iaidoists from obtaining straw while allowing Iaijutsuists to use it.

Tameshigiri can be practiced by anyone. When you begin practicing however, you have a better chance of succeeding if you have been taught the proper mechanics of cutting. A great way to learn this is by practicing Omori Ryu as was pointed out above.

4. The chiburi of Iai-do is not practical, only by wiping the blade on a cloth or a piece of paper would the blade be clean enough to return to the scabbard.

This is true. The Iai-jutsu of the Tenshin Shoden Katori Shinto Ryu has a chiburi that consists of spinning the blade and then hitting the tsuka with a fist. The Toyama Ryu Iai-jutsu uses the exact same circular chiburi as does Omori Ryu. The chiburi "represented" by these motions would not be performed by the swordsmen involved after actually cutting someone or something. An Iaido exponent would doubtless use a cloth too.

5. The noto of Iai-do is too fast and is used only for show, the noto of the classical warrior is slow and demonstrates zanshin (lingering heart, awareness).

The student of Iaido had better demonstrate zanshin or the instructor will soon show its usefullness. As to the quick noto, it might be argued (by me only) that one should be ready for further attacks after finishing one opponent. One man thoroughly dead at your feet doesn't mean that all potential enemies are dead. By taking a long time to do noto you are leaving a suki of the same sort that is left with a slow nuki tsuke. In any case, fast or slow, drawing or sheathing you must be ready to change according to the circumstances. That is fudoshin.

6. The manners and customs of modern Iai-do students are careless. Most of them have a koiguchi that is chipped and scratched.

All beginners have a saya that is chiseled, nobody starts out perfect. Omori Ryu is a school that contains major influences from the Ogasawara Ryu Reishiki. Omori is a school of the manners and customs of the sword. It is also a school where the slow nuki tsuke is done, allowing the student to learn how not to scratch the koiguchi. A poor student of Omori Ryu will have poor manners but that is no fault of Iaido itself.

Nakamura goes on to say that modern practice should be a balance of old and new but the showmanship, sport and competition aspects should be discarded. The link between Kendo and Iaido should be recognized, the shinai is not a sword.

Obata Toshishiro in his book Crimson Steel states, "the Samurai never wore his long sword when seated because it was not worn into the house, yet 'Iaido' as the new sword drawing art was termed taught many sword drawing methods from the formal seated 'seiza' position."

The samurai did wear his long sword when seated. He wore it when he practiced Omori Ryu Iai. At the time the art might have been termed Batto-jutsu, Iai-jutsu or some other name but since the term Iaido did not become popular until the 1930s and since the common people in the Edo period did not practice swordsmanship, the 'Samurai' most certainly practiced Iai-'jutsu' from 'seiza'.

Reid and Croucher in The Way of the Warrior have this to say. "When it is well performed Iaido is a beautiful, almost balletic use of the sword, but it bears little relation to the speed, poise and concentration of the art of Iai-jutsu. The combat value of studying Iaido, especially with a blunt sword, is almost nil, but on the other hand the aim of the adept in this way is spiritual and bodily harmony and growth, not killing power."

If one needs killing power to have speed, poise and concentration, perhaps one should practice with automatic rifles instead of these horridly inefficient blunt swords.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Draeger, Donn F., 1983, The Martial Arts and Ways of Japan, Vol. 3, Weatherhill N.Y. Jones, Trevor, 1989, A Brief History of Iaido, Kendo News #4, April, British Kendo Association.

Mears, Bill, 1990, Yugen Kan Dojo Iaido Manual.

Obata, Toshishiro, 1987, Crimson Steel, Dragon Books, USA Otake, Ritsuke, 1977, The Deity and The Sword Vol. 1, Minato Research and Publication Co. Tokyo Japan.

Reid, H. and M. Croucher, 1983, The Way of the Warrior, Methuen, Toronto. Sato, Kanzan, 1983, The Japanese Sword, Kodansha International, Tokyo. Shewan, Malcolm Tiki, 1983, Iai: The Art of Japanese

Swordsmanship, European Iaido Federation publication.

Warner, G. and Donn F. Draeger, 1982, Japanese Swordsmanship, Weatherhill, N.Y.