The following essay

is excerpted from the Bartitsu Compendium, a comprehensive guide to the

history and practice of E.W. Barton-Wright's "New Art of Self Defence"

which was founded in England in 1899. Barton-Wright was the first

man to deliberately combine Asian and European martial arts to create a

comprehensive system of civilian self defense skills, and his Bartitsu

Club was the first example of the modern commercial martial arts school

in the English-speaking world.

The following essay

is excerpted from the Bartitsu Compendium, a comprehensive guide to the

history and practice of E.W. Barton-Wright's "New Art of Self Defence"

which was founded in England in 1899. Barton-Wright was the first

man to deliberately combine Asian and European martial arts to create a

comprehensive system of civilian self defense skills, and his Bartitsu

Club was the first example of the modern commercial martial arts school

in the English-speaking world.

Proceeds from sales of the Bartitsu

Compendium have been dedicated to creating a memorial plaque for Mr.

Barton-Wright adjacent to the original site of the Bartitsu Club, and

to further research into the art of Bartitsu.

The Bartitsu Compendium (Lulu Publications, 2005, http://www.lulu.com/content/138834

"A system which he termed Bartitsu"

By Tony Wolf

He claimed to have made a variety of improvements upon the native art, producing a system which he termed Bartitsu; but to all intents and purposes that which Tani and Uyenishi demonstrated was Jiu-jitsu pure and simple, and the name Bartitsu was very speedily forgotten.

- Percy Longhurst, "Jiujitsu and Other Methods of Self Defence", circa 1906

There has been a long-standing confusion regarding E.W. Barton-Wright's use of the words jiujitsu and Bartitsu, and the implications of how he chose to present and promote his "New Art of Self Defence". One current take on the subject, common when Barton-Wright's name and art appear in Internet discussions, is that Barton-Wright actually claimed to have invented jiujitsu, or at least that he mis-represented the art to the British public. The truth may be rather more complicated than that. This essay attempts to trace the practical evolution of Bartitsu as a martial art, Barton-Wright's own definition of that art, and the sometimes ambiguous relationship between Bartitsu and jiujitsu.

Percy Longhurst's quote should be understood in context. Longhurst's first exposure to Bartitsu had been in 1901, trying conclusions twice with the Japanese jiujitsuka when they were performing at the Tivoli theatre, and he had been favourably impressed with their skill and art. At that time, evidently, Barton-Wright's "New Art of Self Defence" was still being promoted as Bartitsu, the term used by Longhurst in his subsequent report for Health and Strength Magazine in January, 1902.

There is no doubt that the word was coined by Barton-Wright. He had registered "Bartitsu" Ltd. as Company 59684 with the London Board of Trade in 1898, presumably just after arriving back in England from Japan Curiously, however, he does not appear to have immediately applied the word as the name of his self-defence style.

Barton-Wright's first article on the subject of self-defence was published in two instalments in the March and April 1899 issues of Pearson's Magazine. These illustrate a selection of techniques that are credited to the "Japanese wrestling" tradition, and also a manoeuvre with an overcoat that may be of French origin. Significantly, the first essay makes no reference to either "jiujitsu" or "Bartitsu" by name. Barton-Wright wrote:

It is to meet eventualities of this kind, where a person is confronted suddenly in an unexpected way, that I have introduced a new style of self-defence, which can be very terrible in the hands of a quick and confident exponent. One of its greatest advantages is that the exponent need not necessarily be a strong man, or in training, or even a specially active man in order to paralyse a very formidable opponent, and it is equally applicable to a man who attacks you with a knife, or a stick, or against a boxer; in fact, it can be considered a class of self-defence designed to meet every possible kind of attack, whether armed or otherwise.

His subsequent description is, essentially, of jiujitsu. In a brief introduction to the second instalment, he wrote:

Readers of the March Number will remember that I described therein a few of the three hundred methods of attack and counter attack that comprise my New Art of Self-Defence, to which I have given the name - "Bartitsu."

This suggests that he may have decided to apply the name to his martial arts system in between writing the two articles, or as an afterthought.

For the benefit of new readers, it will be well to point out that my system has been devised with the purpose of rendering a person absolutely secure from danger by any method of attack that may arise. It is not intended to take the place of boxing, fencing, wrestling, savate, or any other recognized forms of attack and defence. This, however, is claimed for it - it comprises all the best points of these methods, and will be of inestimable advantage when occasions arise where neither boxing, nor wrestling, nor any of the known modes of resistance is of avail. The system has been carefully and scientifically planned; its principle may be summed up in a sound knowledge of balance and leverage as applied to human anatomy.

This is unfortunately ambiguous. If Barton-Wright meant that Bartitsu (or jiujitsu) comprised the best points of the various styles he listed - in that the Japanese art included kicks, punches, throws, etc. that were comparable to techniques found in the other styles - then at this stage, he was simply presenting a re-branded jiujitsu. On the other hand, if he meant that Bartitsu literally also incorporated boxing, fencing, wrestling and other techniques, then these articles were presenting jiujitsu as one aspect of a larger art.

In the second Pearson's installment, he wrote that "the majority of these feats, I may explain, (have been) elaborated from the Japanese style of wrestling," but because it is unknown which of the three jiujitsu ryu (schools) he studied in Japan is represented in the articles, it is hard to judge the degree of elaboration that may have taken place. It has been pointed out that one of the techniques, a restraint hold applied to the leg of a prostrate opponent, is more commonly found in the curriculum of Lancashire (Catch-as-can) wrestling than in classical jiujitsu, but this is not conclusive.

In December, 1901, Mary Nugent wrote:

As is explained on the stage every night by (Bartitsu's) introducer, there is a secret method of wrestling known, and very covertly practised, in Japan, and that is called Jujitsu - the word "jitsu", freely translated, meaning "to a finish."

That was a very free translation indeed, as jiujitsu is more accurately defined in English as "the art of yielding". It is possible that Barton-Wright's knowledge of the Japanese language was not up to the task, although he had been resident in Japan, working as an industrial engineer and/or surveyor, for three years prior to his return to England. It is also possible that he simply felt that the "fight to a finish" translation was more dramatic. In any case, I have not been able to discover an accurate definition of the word jiujitsu in Barton-Wright's published work, nor in any reports by others who had interviewed him or witnessed one of his many public demonstrations.

In sum, it is evident that Barton-Wright wanted his readers and those members of the public who attended his exhibitions to identify this "New Art" closely with himself. It is possible that he was being deliberately ambiguous, waiting to gauge the reaction of the public to his articles and demonstrations, and especially to those to be performed by the jiujitsuka who were en route from Japan, before committing himself to defining what Bartitsu actually was. However, it's worth noting that Barton-Wright did not claim to have invented jiujitsu, merely to have introduced Bartitsu; and this distinction seems to have been too subtle for many of his contemporaries to grasp.

This all changed once Barton-Wright had opened the doors of the Bartitsu Club, and at this stage he openly embraced an eclectic philosophy towards self defence training. An anonymous article (possibly authored by Barton-Wright himself) appearing in the Black and White Budget of December 29, 1900, included the following statements:

... no trouble or expense has been spared in introducing Mr. Barton-Wright's novel system of self-defence, which is Bartitsu spelt another way, into this country.

Bartitsu has been devised with a view to impart to peacefully disposed men the science of defending themselves against ruffians or bullies, and comprises not only boxing but also the use of the stick, feet, and a very tricky and clever style of Japanese wrestling, in which weight and strength play only a very minor part.

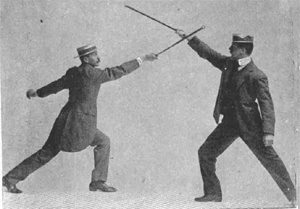

The Bartitsu style of stick play, besides being most graceful, is certainly most practical and telling.

Another branch of Bartitsu is that in which the feet and hands are both employed, and which is an adaptation of boxing and Savate.

Bartitsu therefore resolves itself into this: if one gets into a row and plays the game in the recognised style of English fair play - with fists - the opponent will very likely rush in and close, in order to avoid a blow. Then comes the moment for wrestling in the secret Japanese way. Instantly the unwary one is caught and thrown so violently that he is placed hors de combat, without even sufficient strength left to retire unassisted from the field.

Again, should it happen that the assailant is a better boxer than oneself, the knowledge of Japanese wrestling will enable one to close and throw him without any risk of getting hurt oneself.

The art of walking-stick defence is taught for a variety of purposes. It may be used safely against an opponent armed with a dagger - in which case the latter has no chance at all - against a quarterstaff, against kicking, boxing, etc.

Bartitsu also comprises a system of physical culture which is as complete and thorough as the art of self defence.

It is clear that by the time this article was written, Barton-Wright's definition of Bartitsu encompassed virtually every subject and system taught at the Bartitsu Club, with the object of devising a truly diverse and eclectic self defence method.

By February 1901, with Tani and other jiujitsuka resident in London and the Bartitsu Club in full operation, Barton-Wright was able to confidently define Bartitsu during a lecture for the Japan Society, and go further by distinguishing it from both jiujitsu and judo:

THE Lecturer said that before commencing to discuss the pros and cons of Ju-do and Ju-jitsu, he wished to explain and make clear the meaning and derivation of "Bar-titsu." "Bar-titsu" was derived from his own name, Barton, and the Japanese word Ju-jitsu, which meant fighting to the last. When he spoke of Bar-titsu, he therefore meant real self-defence in every form, and not in one particular branch. Under "Bar-titsu" he comprised boxing, or the use of the fist as a hitting medium, the use of the feet both in an offensive and defensive sense, the use of the walking-stick as a means of self-defence in such a way as to make it practically impossible to be hit upon the fingers. Ju-do and Ju-jitsu, which were secret styles of Japanese wrestling, he would call close-play as applied to self-defence.

The fact that Barton-Wright felt it necessary to make this distinction may imply that he was beginning to feel the heat as a result of his earlier ambiguity. Certainly, once the Japanese jiujitsuka arrived, their exoticism and skill at "taking on all comers" made better press than Barton-Wright's esoteric Bartitsu. He may have been distancing himself slightly from jiujitsu per se, and simultaneously keeping it within his reach, by stressing that it was actually included within Bartitsu, as another branch comparable to stick fighting and kick boxing.

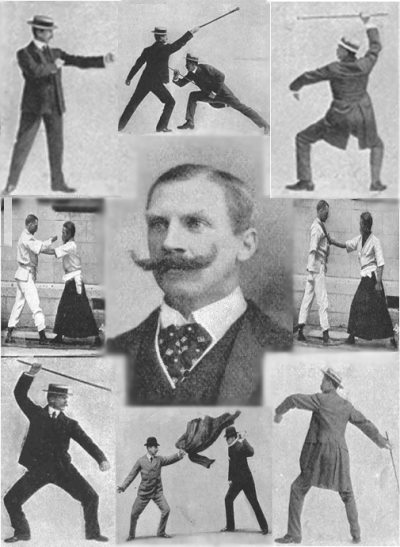

Perhaps most significantly, by this time - ten months after he had written the Pearson's magazine articles - Barton-Wright had also been working intensively with Pierre Vigny. Like Barton-Wright, Vigny was primarily interested in self-defence training and was experienced in a wide range of different fighting styles. Vigny had already been working as a professional self defence instructor for some years prior to joining the staff at the Bartitsu Club. He was nine years Barton-Wright's junior, but his walking-stick defence system impressed Barton-Wright, who seems to have immediately folded it into Bartitsu. In fact, it is difficult to distinguish between Bartitsu and the Vigny system as it was described in the years that followed their association at the Club.

Post-1903, however, Barton-Wright's name seldom appears in connection with self defence instruction. The details as to how Barton-Wright was effectively sidelined from the movement that he had started may be of some interest here.

Barton-Wright's main interest throughout seems to have been in promoting Bartitsu as a self defence system; the sporting aspects, his forays into professional wrestling promotions, etc. appear to have been sidelines as far as he was concerned. Also, most of Barton-Wright's own jiujitsu training appears to have been in traditional jiujitsu ryu-ha, namely the Shinden Fudo-ryu and the Tenshin-shinyo ryu. As such, it is likely that most of his training had taken the form of kata (pre-arranged exercises in which disabling techniques can be safely simulated) rather than randori (freestyle, "sportive" combat in which the most dangerous techniques are disallowed).

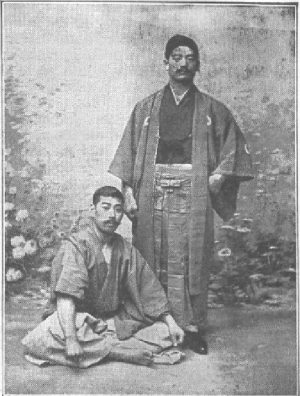

Barton-Wright had also taken some lessons with Jigoro Kano, the great reformer of the classical Japanese unarmed combat arts who was, at that time, seeking to promote his syncretic style of Kodokan judo, and a pedagogy that drew heavily upon the Western model of physical education. One of Kano's goals was to revise the "battlefield arts" of jiujitsu into a system that could be safely practiced as a healthy, modern sport and as physical education; a form of enlightened jacketed wrestling. It is possible that he sent the Tani brothers, Yamamoto, Uyenishi and others to England with that goal in mind.

In any case, while the British public and journalists were intrigued by Barton-Wright's self defence demonstrations, they were much more interested to see the art applied in earnest competition. Tani, Uyenishi et al. were far better qualified to take on all comers as professional wrestlers and, as slightly built foreigners, they made better copy doing so. As they were competing for sport, they were obviously unable to resort to the more damaging "tricks" - joint destructions, atemiwaza (striking techniques), etc. that Barton-Wright was fond of demonstrating, and that had featured prominently in his Pearson's Magazine articles. This meant that they were, in effect, applying Kano's ideal of competitive judo in most aspects bar the name.

The origins of shiai (competition) in jiujitsu are not clear. In Tokyo almost twenty years previously, inter-ryu competitions had been held to determine which jiujitsu teachers would gain the coveted job of instructing the Japanese police force. Unfortunately there are no records of the rules these contests had been fought under. However, researchers suggest that atemiwaza were very likely banned and that contests may have been decided by clean throws and by the application of submission holds on the ground.

The rules of Go Kyo no Waza were first published in 1895. They specified that any techniques that could not be applied at full strength and speed without causing injury were to be relegated to kata practice. All other techniques were to be allowed in challenge matches. A single judge was to decide the winner or to declare a draw should the fighters be evenly matched.

By 1899 Jigoro Kano's organisation, the Dai Nippon Butokukai, had banned locks of the fingers, toes, wrists and ankles in jujutsu/judo contests. Then, in July 1906, educators and judo teachers from across Japan came together in Kyoto to agree upon techniques and pedagogies that would be acceptable to the Japanese Ministry of Education. Again, Professor Kano led the way in modifying the art to the point where it could be endorsed for inclusion in the physical education curriculum.

It seems likely that either Tani, Uyenishi and the other Japanese jiujitsuka in London were following the Kodokan development of judo/jiujitsu as a sport, or that their circumstances as professional wrestlers engendered a kind of parallel evolution. It is evident that their "brand" of jiujitsu diverged from that which E.W. Barton-Wright had been promoting via his articles and came to resemble Professor Kano's new art of judo. There is no reason to doubt that the Japanese instructors were also skilled at the kata-based self defence techniques, but their books -"The Game of Ju-Jitsu for the Use of Schools and Colleges" by Tani and Miyake (1906) and Uyenishi's "The Text Book of JuJutsu as Practiced in Japan" (1905) - placed heavy emphasis upon the less lethal aspects of the art. In this atmosphere of modernisation, Barton-Wright's traditional self-defence kata may have seemed out-dated.

At some point during 1902, Barton-Wright and Tani had a falling-out; according to Barton-Wright's report forty-eight years later, there was an argument over Tani's missing appointments, for which Barton-Wright proposed to dock his wages. The argument escalated into a physical fight, which Barton-Wright claimed to have won. Shortly thereafter, Tani joined forces with the veteran music hall strongman and promoter William Bankier ("Apollo"), under whose management he continued his successful professional wrestling career.

There can be no doubt that Bankier was a better promoter and manager than Barton-Wright, nor that there was little love lost between them; Bankier was later to note that when jiujitsu was first demonstrated in England, "the art was described as farcical, and the demonstrators knockabout comedians," which sounds like a professional's contempt for Barton-Wright's abilities as a promoter. In any case, under Bankier's management, Tani's jiujitsu became famous throughout England, at the expense of Barton-Wright's Bartitsu.

At about the same time, the Bartitsu Club closed down; Percy Longhurst was later to suggest that the enrollment and tuition fees had been too high.

By April, 1903, Pierre Vigny was operating his own school of self defence in London. It is not clear whether this school was in competition with the Bartitsu Club, or whether the latter had already closed its doors by that point. In any case, the Club seems to vanish from the historical record after early 1902. Vigny's school, tournaments and exhibitions attracted a good deal of positive press, similar to that attained by Barton-Wright just a few years earlier, until Vigny returned to Switzerland in 1912.

Meanwhile, Tani, Uyenshi and others opened their own jiujitsu dojo in London, which then

passed to their students, and there emerged a minor jiujitsu publishing

boom. The golden years of European jiujitsu lasted throughout the first

decades of the twentieth century. By 1916, more dangerous

techniques had been banned from shiai (competition) judo, leading

further away from the battlefield skills of traditional jiujitsu and

paving the way for the development of modern judo as an Olympic sport.

Meanwhile, Tani, Uyenshi and others opened their own jiujitsu dojo in London, which then

passed to their students, and there emerged a minor jiujitsu publishing

boom. The golden years of European jiujitsu lasted throughout the first

decades of the twentieth century. By 1916, more dangerous

techniques had been banned from shiai (competition) judo, leading

further away from the battlefield skills of traditional jiujitsu and

paving the way for the development of modern judo as an Olympic sport.

The antagonistic jiujitsu aspects of Bartitsu were spread further afield by former Bartitsu Club instructor Armand Cherpillod, and the type of jiujitsu that appeared in his books and others published in Germany, Switzerland and other Continental European countries through to the 1940s tended to resemble Barton-Wright's self defence art more than the sport jiujitsu popularised by the Japanese instructors. However, some of the books published by the students of Tani, Uyenishi and Miyake did harken back to the more combative style that Barton-Wright appears to have introduced to England, further suggesting that although the Japanese instructors may have been more focussed on competitive jiujitsu, they also taught the full complement of self defence techniques.

It remains for us to trace the evolution of Barton-Wright's ideal of an eclectic self defence system combining the best of Japanese and European martial arts, including but not limited to jiujitsu and judo, which had begun to take shape during the heyday of the Bartitsu Club.

In a sense, this tradition was immediately picked up by Pierre Vigny, albeit not as "Bartitsu" per se; it seems likely that Barton-Wright and Pierre Vigny simply had common goals and methods, and that their collaboration at the Bartitsu Club had led them both in similar directions. Either way, there is little to distinguish between Bartitsu and Pierre Vigny's self defence system as it was described in the years following the demise of the Bartitsu Club.

Perhaps the most detailed and developed applications of the Bartitsu philosophy emerged in the self-defence manuals published by French defence dans la rue instructors Jean Joseph Renaud and George Dubois, who had trained in jiujitsu with the Bartitsu Club instructors and went on to fold it into their own eclectic self defence systems.

Ironically, Barton-Wright's philosophy was also to find expression in the work of Percy Longhurst, who acknowledged that:

... I would not say"and let this be clearly under-stood" that Jiu-jitsu is an absolutely infallible system: such still remains to be discovered, and probably it never will be, circumstances and the personal element wielding so large an influence. The person knowing Jiu-jitsu is not, ipso facto, rendered invulnerable against injury by personal assault; he will not inevitably overcome any chance assailant, though the odds are in his favour. But it is an extremely valuable form of self-defence, and, in conjunction with boxing, forms the nearest approach to the perfect"and un-discoverable"system.

Longhurst's system, as set forth in his book Jiujitsu and other Methods of Self Defence, also included aspects of Vigny's stick fighting art, Cumberland-Westmoreland wrestling and savate, and one throwing technique that he specifically credited to Barton-Wright.

May 2006