JManly: John, thanks for taking the time to talk to us. Could we begin with a precis of your fencing education and experiences as a student, competitor and teacher?

JManly: John, thanks for taking the time to talk to us. Could we begin with a precis of your fencing education and experiences as a student, competitor and teacher? Journal of Manly Arts

August 2003

by Tony Wolf

Editors note - this interview is the first of a series to be featured at the Journal of Manly Arts over the coming months, describing the modern practise of martial arts and combat sports originating between 1776 and 1914. To begin we present a discussion with fencing Maestro John Sullins, whose curriculum at the Tri-Cities Academy of Arms includes several different Classical-era fencing styles.

JManly: John, thanks for taking the time to talk to us. Could we begin with a precis of your fencing education and experiences as a student, competitor and teacher?

JManly: John, thanks for taking the time to talk to us. Could we begin with a precis of your fencing education and experiences as a student, competitor and teacher?

John Sullins: Sure. As is the case with most American fencers I had a great interest in fencing at a very early age but was unable to find a place to learn. I found a club when I was ten and practiced there for a few months. One night there was a serious accident in the club where a blade broke and pierced the bib on the mask of one of the fencers wounding him in the neck. This accident terrified the parents of my friend with whom I had been getting a ride to the salle, so my early career came to an end when they stopped going.

I was unable to fence again until I began my college studies in the early eighties. I enrolled in a fencing 101 class which I took over and over each semester. This was not enough training so a few friends and I began driving into San Francisco to study at the Letterman Fencing Club in the Presidio Army base. Here I studied with the late Dr. O'Brien who was in his 70's at the time and it was from him that I began to sense the deep living history that can be experienced while working with a highly trained master. We would take a lesson from him, fence until ten or so in the evening then go out to a diner and listen to him tell stories of the fencing of his generation. The stories were filled with anecdotes of great west coast fencers such as Hans Hallberstadt-- the founder of the other great club in San Francisco who were our rivals, Helena Mayer, Aldo Nadi, Ralph Faulkner and others. What struck me most about his stories was how different fencing was in the early part of the twentieth century. He had stories of Mexican duelists, and remembrances of a sabre assault at arms held on horseback on the Presidio parade grounds he had witnessed as a boy some time before WWI.

Letterman was a serious sport-fencing club with national and international aspirations. A few of the members had Olympic goals and so we learned a highly competitive style of fencing there. We practiced all week and competed on the weekend. I never broke into the highest level of competitors there but I did fence and train with all of the best fencers in the club. Through this experience I learned about the San José State fencing team. It was coached by the great American competitor Michael D'Asarro and I had to get a berth on that team. It was an inexpensive state school but it regularly beat the big private universities. A great number of the US Olympic fencers came from that team and it had produced more than its share of NCAA All-American athletes. So I transferred to San José State in 1986.

My dreams were quickly crushed though as unbeknownst to me, the team was in the process of imploding due to a scandal and was disbanded the very semester I arrived. I was despondent, but there were some strong remnants of the program still in place. With the demise of their team a number of the team members and assistant coaches had set up the San José Fencing Center in an old Masonic temple. This was a great club with high quality coaches and the Masonic inner sanctum made for a inspiring fencing salle.

JManly: That sounds intriguing. Can you describe the setting?

JS: It was fairly run down but it was still a great space. It had that Victorian Gothic feel with carved wood fixtures, hard wood floors and walls, and a dais on one end of the large hall where we fenced. At one point someone had found a number of old fencing pictures and ads for classic era tournaments, and when these were hung up it really added to the atmosphere. The fencing center was able to rent this hall for next to nothing as the landlord was using the place as a tax write-off. Unfortunately a few years later he was able to find a paying tenant and kicked the fencers out. They now meet out in the suburbs of San Jose in a much less inspiring facility.

I continued my competitive career at this club for a year working mostly with Maître Peter Buchard before I found out about the Military Masters Fencing Program at San José State University that is run by Dr. William Gaugler. I quickly enrolled in this program and it changed my life. Through Dr. Gaugler I met and worked with these great fencing masters: Master at Arms Ralph Sahm (1986 to 1997); Maestro Lucio Nugnes (1989); Maître Daniel Revenu (1988); Maestro Ferenc Marki (1988); Maestro Niccolo Perno (1988); and Maestro Enzo Musumeci Gerco (1988). I continued with this program for over ten years and earned my Military Instructor at Arms (1988), Military Provost at Arms (1989), and Military Master at Arms (1994). This is a unique program that recapitulates the curriculum of the Italian Military Fencing School and there is nothing like it on the planet now that the original in Italy is gone.

JManly: Can you describe the differences between that curriculum and a more orthodox competitive program?

JS: The Military Masters School in Italy had a long history so the answer to that question depends on the time period your interested in. By the end of its tenure what was taught there was not much different from the Olympic style fencing found throughout the world. On the other hand, the Military Masters School that Dr. Gaugler has been running for the last twenty years in San José is quite different from what is found at most clubs and training programs today. First of all it is dedicated to teaching fencing pedagogy so its main thrust is producing the highest quality fencing masters, not just medal winning competitors. I have taken lessons from Olympic fencers in the past and they are rarely good teachers. Their training is unburdened by theory or by the study of how to teach other people to fence. Their fencing masters did all that sort of thinking for them, so when they retire and go off to teach they are not as qualified to do so as a person who has been specifically trained in all the details of the theory and how to apply that theory to any specific fencer.

Second, we were trained in the traditional Italian school. This was painstakingly researched by Dr. Gaugler through his studies with Aldo Nadi in Los Angeles and then later in Italy while he was earning his doctorate in Florence and then teaching at universities in Europe. He was able to learn the traditional school from living masters and then transplant that knowledge to the US when he returned here in the seventies. Oddly enough, our program is more "Italian" then most of the large Italian schools. When we would invite Italian masters to our program they were universally dumbfounded to find us practicing the old school. Some reacted as if they thought we were a bit crazy for doing so. They, of course, had been busy dismantling their own traditions in favor of the modern international style that originated in Eastern Europe.

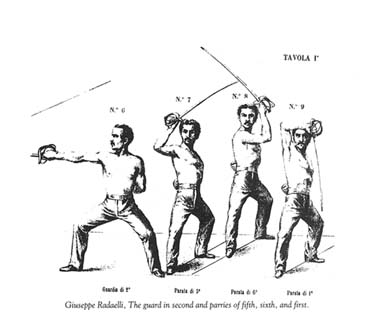

Briefly put, the main difference is a respect for the blade or point in line, maintaining the Italian numbering system for parries and hand positions, constant drilling in counter attacks, maintaining the Radaellian sabre tradition, and a deep respect for, and study of, the history of fencing. We also spent a great deal of time comparing and contrasting the Italian school with the other traditional schools found in the French method and Hungarian Sabre. Each candidate for the Master's degree had to write a lengthy thesis and mine was a comparison of Italian and Hungarian Sabre pedagogy.

JManly: What was your inspiration to begin re-constructing classical-era fencing styles?

JS: Oddly enough this was not my main goal when I began fencing. I was completely bitten by the competition bug and wanted to fence in the Olympics or at least on the international scene. My time with Dr. Gaugler, Maestro Sahm and the stories of Dr. O'Brien gradually worked on me and I began to realize that fencing is not now what it used to be. Change is to be expected in any human endeavor but the change wrought on fencing has not been positive.

JManly: In what way?

JS: Personally I dislike the dumbing-down of fencing technique in favor of speed and footwork. The game as it stands today is just not that compelling to watch. What I find exciting is when the fencer demonstrates his or her ability to out think his or her opponent. The modern international style consciously rejects the value of technique in fencing. The game, for them, is only about doing what it takes to make the light go off. If that means taking advantage of the flexibility of the blade to simply wrap around their opponents defenses, then so be it. I admit that that is probably what one needs to do to win on the international stage today but this is killing the sport. The main problem that high level fencing faces is attracting an audience, especially a TV audience. Well, the audience expects to see a sword-fight and what they get is a strange game of tag. Naturally they find it uninteresting. So what do the powers that be in fencing do? They dress us in pastel uniforms and fishbowl helmets. I think the answer is simple. Give the audience a sword-fight! Our predecessors in this sport knew how to do that so that is where I chose to draw my inspirations from. For me, the future of fencing is to be found in its past.

Dr. Gaugler had studied with Aldo Nadi and many of the great Italian fencers of the classical period during his time living in Europe in the 50's and 60's. He was committed to working us to the standards of this time. We were learning a style of fencing that few in the world still practiced. As my studies continued I realized how special that knowledge was. I had received the living tradition of generations of fencers and I could not turn my back on that, I had to press even deeper into that territory. I am especially interested in classical Italian Sabre. This is a tradition that is desperately close to extinction and I have been working hard to preserve it and to revive the construction of the wonderful Italian broadswords that were used by Radaelli, Masiello, and Parise in the mid- to late-1800s. On a trip to Italy with Dr. Gaugler, Maestro Sahm and other students in the Masters Program, we visited a antique arms shop where we saw Radaellian fencing sabres and a matched pair of Italian dueling sabres. The sight of these made a big impression on me and from that time I have been learning as much as I can about the use and history of that weapon.

JManly: What were some of the challenges you had to face as you began reconstructing the classical Italian sabre style?

JS: There are many. Classical sabre is the most exciting weapon in fencing. The blades ring, spark, and flash in the light as they clash together. The actions are bold and powerful and the hits are solid and convincing. It is a perfect weapon to fence in front of crowds and we have had great success with it. Unfortunately there are no companies making blades that are appropriate. The fencing sabre has been atrophying in size and weight for a hundred and fifty years or more. So when we wanted to reintroduce this weapon we had to find antique fencing weapons that are over eighty years old. Surprisingly these blades still have a lot of fight left in them and they are wonderful examples of the brilliant work that was being done in Germany, in the blade factories in Solingen before the war. These companies suffered total destruction in WWII so the art of creating them has been totally lost.

Using a proper blade is critical, but not everyone can get their hands on an antique blade, so I had to search the world for a new maker. It took me six years to find a smith that would take on the job. Quite a few thought they could do it but after seeing the antique blades they quickly backed out saying it would be impossible to get the right temper to the blade. These blades are the same size and weight as a dueling sabre but are blunt and flexible. Getting the temper right is a true art. The blade has to flex when it hits but can't vibrate through he air while one is making a cut. The antiques we have will flex almost ninety degrees and snap right back to true and sail through the air in a perfect arc while one makes a circular cut.

Recently Adam at Popinjay Armories has succeeded in making very credible reproductions that work quite well. This is a big coup for us and we are very excited about it. We have been able to hold a competition using the blades that went very well and we practice with them every week. We have more competitions planned and I can only see this weapon getting more popular as other fencers are exposed to it. The other problem has been in translating the nineteenth century sabre texts so that others can be as inspired by them as I have. The Italians wrote large well-illustrated treatises on the dueling sabre and these deserve to be well known and studied. Most people that are interested in the dueling sabre or broadsword only know Hutton's Cold Steel. That is a fine book but if you want to recreate this weapon you have to go to the sources that inspired Hutton himself. I have been slowly working on a book on classical Italian sabre where I hope to be able to lay out the entire school with plenty of photos and illustrations so that this material can be made a bit more accessible.

JManly: As we wrap up I'd like to focus a bit more on the research and reconstruction process. For example, along with the classical sabre I know that your school has been very active in re-creating other fencing sports of the 1800s and early 1900s. Can you tell us a bit more about this - your inspirations and the challenges that you have had to face?

JS: Right, what I want to eventually achieve is a full recreation of a 19th century fencing salle where we would fence every weapon that could be found at that time - foil, dueling sword, sabre/broadsword, singlestick, great stick, cudgels, cane, quarterstaff, and bayonet fencing. So far we have trained extensively in all except the last four on that list but we are making headway on the other weapons as well. The main problem has been trying to find blades that are close to those used traditionally.

JManly: How important is exact historical re-creation in terms of equipping your fencers, etc.?

JS: I do believe that one needs to fence with nearly exact recreations of the historical weapons as is possible. Taking safety into account, of course. We already talked about this problem with the sabre but it exists with the other traditional weapons as well. For instance there are no blade makers that make Italian foil and epee blades that have true ricassos and are the right length and balance. They are also not stiff enough and are much lighter in weight then those of the nineteenth century. I am hoping that as the classical fencing movement grows we will be able to convince the fencing blade makers to cater to our needs. This is one of the reasons I like the various stick fencing forms so much, the weapons are readily available.

Protective equipment is a bit of a problem. We do our best to try to make the equipment look as close to the originals as possible but we are not against using modern materials since there are so many different pads from other sports to chose from and they increase the safety of the sport. I find the biggest problem to be the helmets. A good broadsword helmet has not been on the market since before WWII. This is a real problem and I hope we can solve this as a community since it is a problem whose solution is well beyond the abilities of individual fencers or clubs to resolve.

JManly: What has been the reaction to your historical experiments from the more orthodox fencing community?

JS: Mostly they do not understand what I am doing until they see us fence with the broadswords, then I can see their interest even when they try to hide it. They have nothing like that weapon and are clearly envious of the reactions it gets from non-fencers during demos. Modern fencing is completely enigmatic from the point of view of the casual observer. Classical fencing filled with technical beauty but at the same time it is real and visceral and one need not be a specialist to understand what is going on. The only down side is that it takes a long time and diligent study to become skilled at it and unfortunately the skills of a modern fencer do not translate well. This makes it hard to create converts from their ranks, as it requires a painful period of relearning. I know exactly how this feels. When I first entered Dr. Gaugler's program, he politely but firmly informed me that I had to unlearn everything I thought I knew and start from the beginning again. I nearly quit a number of times but I am very happy I was able to swallow my pride and complete the program. It is actually easier and quicker to train people brand new to the sport. My club has quite a number of young fencers, our youngest is seven, I wish I had had this quality of training beginning at that age. If we can keep this up the next generation of classical fencers will be highly skilled and could give the status quo in fencing a real run for their money.

JManly: What is your vision for the future of the classical fencing arts?

JS: I want fencing to achieve again the status it had prior to the advent of modern fencing. I would like to see the return of the grand assaults at arms, the gala, and the proud salle d'arms. They will not be exact replicas of course but fencing lost its way in the last century and we are going to have to work hard to find again that lost potential in this century. I already see evidence of this happening, we are just one of many other clubs and programs that are working towards this goal. Just in my local area alone we have Maestro Adam Crown, and Maestro Martinez who have been at this longer than myself and are producing many fine classical fencers who are keen on changing the world. Soon we will have enough classical fencers world-wide to create a real alternative to the travesty that passes for fencing at the international level.