Donald Dinnie

By Glynn A. Leyshon

Adapted from Of Mats and Men: The Story of Canadian Amateur and Olympic Wrestling from 1600 to 1984 (London, Ontario, Canada: Sports Dynamics, 1984). Copyright © Glynn A. Leyshon 1984, 2001. All rights reserved. Reprinted by permission.

By the mid-nineteenth century, professional wrestling was a booming spectator sport in Europe, and it wasn't far behind in North America. For example, the Scottish wrestler and strongman Donald Dinnie began a world tour in 1877 that included a visit to Canada. He earned as much as £300 for a single match [EN1] in a long career in which he was said to have won 2,000 matches. [EN2] In light of the fact that there was no income tax at the time, and given an index for inflation, that sum multiplies by at least 30 times in present standards. Not surprisingly, then, the prize ring became an enormous attraction for strong men from all over the world.

The setup of the ring for wrestling was very similar to that of boxing, both in physical appearance (i.e., a roped square) and in format. Squabbling over rules (Greco-Roman versus collar-and-elbow versus Cumberland versus Lancashire, etc.) was often a pre-match hype. So too were the challenges that any man, apparently, could have printed in a local paper. The following item appeared in the Toronto Daily News in 1901:

Charley Brennan, the Broadway baseball club star, called at this office today and announced his willingness to wrestle Bill Kirby a mixed match at 145 lbs. At $50.00 a side at any place within two weeks time. Chris Fagan, the champion clog dancer, is also after Kirby's scalp. Chris will box Bill under the conditions of his recent challenge. [EN3]

A few days later the following also appeared:

Prof. Moriarty on behalf of J.A. Jackson is out with an offer to throw both Kirby and Brennan twice within the hour, catch-as-catch-can wrestling. [EN4]

The prize ring and the challenges were not restricted to any single area of Canada. In British Columbia, for example, similar events were in vogue. A match reported from 1888 is typical. A.J. Smith of Nanaimo and D. Cameron of New Westminster met at the Philharmonic Hall in Victoria for a prize of $250 a side. The match was Greco-Roman with two out of three falls and French rules were used. Admission was set at $1.00 with back seats 50¢. A round ended on a fall, and there was an indeterminate rest period that lasted anywhere from 10 to 15 minutes. Smith was actually from Quebec while Cameron was from Ontario. Both men weighed about 190 lbs. The bout, which lasted one hour, was won by Cameron, who reportedly had more skill than the stronger Smith. Being a prizefight, there was, naturally, betting on the outcome, and the odds were on Cameron at even money. [EN5]

Sometimes the wrestling prizefights took the form of a tournament, a departure from the boxing format. In such tournaments, a sponsor might offer the prize money and, in addition, each wrestler would agree to put up so much a side. In other words, they would pay into a pot to be awarded either for the ultimate winner, or for their individual matches. Gate receipts and side bets also sweetened the reward. One such tournament, held in Buffalo, New York, in 1883, featured six wrestlers, including a Canadian from Ottawa named Pat O'Donnell. There were no weight classes and the rules could be changed by mutual consent between contestants. O'Donnell, wrestling in a catch-as-catch-can match, was pinned by an American named Gallagher who used a "grapevine twist." Gallagher then wrestled another opponent named Thompson who was fifty pounds heavier, in a side hold match (similar to Cumberland style, but each contestant was fitted with a leather harness). A modern wrestling enthusiast would be aghast at the discrepancy between weights, but even more so at the description of the end of the match: "Thompson had Gallagher on his back with two shoulders down and trying to force his hip onto the boards when time was called." [EN6]

Pinning a man (these were Cornwall and Devon rules) was no easy matter! The bout between Gallagher and Thompson ended in a draw at 22-1/2 minutes, which means there was some time limit agreed to beforehand, probably because of the length a tournament could run. The winner of the six-man tournament was a gentleman named Ross, who received a medal and $500. Gallagher, second, received $350; Thompson, third, a reward of $150. The Canadian O'Donnell, finished fourth "out of the money." [EN7]

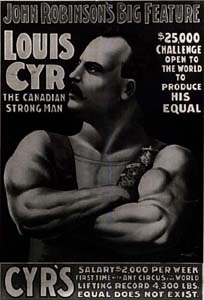

The European influence established that the professional wrestlers be, for the most part, big men. The simple reason for this was that, first, there were no weight classes, and, second, the Greco-Roman or Old Norman style was initially favoured. This style, as with the Cumberland and Westmorland style, favoured a big man because in taking the starting hold a shorter, smaller man had difficulty trying to reach his taller, bigger opponent. [EN8] While smaller men did wrestle, the prize money and attention were showered on the big men. George Hackenschmidt, "the Russian Lion," was typical of the professionals of the era: he was big, strong, and foreign. Even the few Canadians in competition, such as Louis Cyr or the giant, Beaupré, were huge. The latter was reported to be 8'2" tall and weighed 400 lbs. In a match between Cyr and Beaupré, the former won with a bear hug. [EN9]

A typical professional wrestling bout was similar to one which took place in Montreal in 1876 between Professor Treher, Champion of Gaul, and Heygster, the Oak of the Rhine, for a purse of $1,000 (i.e., $500 a side) and the gross receipts. Professor Treher weighed 196 pounds., stood 5'6", and had a 40" waist. Heygster was 5'7", weighed an incredible 304 pounds, and had a 54" waist. Note that both were European, both were big, both had a title, and the purse was large. Heygster won three out of five falls (or "clinches") with what must have been some exciting manoeuvers. Professor Treher would have needed all his academic background to figure a way to lock hands around Heygster, who was nearly as round as he was tall. [EN10]

There are some puzzling contradictions in regard to wrestling in Canada during this period. While in neighbouring Vermont, collar-and-elbow wrestling flourished, indeed blossomed in the late 1800s, there is no evidence of any such enthusiasm in Quebec. From 1848 to 1896 there were inestimable competitions in Vermont. One, in 1885, drew 300 contestants. [EN11] These were strictly amateur collar-and-elbow matches and anyone over 5'7" and 150 pounds was considered large. Yet across the border in Quebec there was little activity. The Montreal Athletic Games in 1843, for example, included a collar-and-elbow tournament with a prize of £5. It was, however, taken uncontested by a gentleman named Eastcott. Upset that the event was won so easily, a little Irishman named O'Connor later challenged Eastcott for the prize in a private match and beat him easily. [EN12] (It is interesting to note that Wilson, author of The Magnificent Scufflers subscribes to the idea that collar-and-elbow wrestling originated either in Ireland or Cornwall and further that Vermont was heavily settled by the Irish who practiced the sport there. [EN13] It is more than possible that O'Connor came from Vermont to win Canadian money.)

With a hotbed of freestyle, or collar-and-elbow, wrestling within a few miles of its border, why did the habitants of Quebec not become involved in wrestling? Oh, there were a few such as the aforementioned strong man, Louis Cyr, who on occasion would bear-hug another strong man into submission, but Cyr was not a wrestler, he was a circus strong man. [EN14] It is possible to attribute this lack of following to two factors: the small population in Canada generally, and the influence of the church, at least in Quebec.

In 1870, the population of Canada was a mere three million. [EN15] (The great period of immigration was to come between 1903 and 1914.) Canada was settled first by the French. As early as 1666, there were some 3,500 French inhabitants in the province of Quebec, of which 2,500 were peasants. The seignorial system and the church combined to make sure that peasants stayed peasants. There was no press, no higher education, and all instruction was in the hands of the clergy. [EN15] According to Davidson, the habitants were prolific, rudely prosperous and contented - and incredibly ignorant. The clergy ruled everyone in the colony except for the disreputable couriers-de-bois who, as their name implies, ran free of official surveillance. [EN16]

As Kent points out in his book A Pictorial History of Wrestling, the church could have had a negative influence on the growth of wrestling. The activities of the Methodist Church, for example, helped to weaken the hold of wrestling in the West Country of England in the mid-1800s. [EN17] Wrestling was also tainted somewhat by its association with the prize ring. In some instances, the police, even in Canada, would not sanction a match because of the potential for brutality or even a fatality. The same type of local ordinance that often forced bare-knuckle fights out of the cities into the countryside sometimes hampered wrestling. The following appeared in a Toronto paper in 1901:

Quite a delegation of local sportsmen will journey up to Georgetown Saturday night. As the stranglehold is not barred, the Police Department would not grant a permit for the contest in this city. [EN18]

Thus the situation of wrestling in Canada during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was two-sided. The sport was widely followed in the professional arena, but smouldered like a peat fire, underground, in the amateur field. The few amateurs whose deed were distinctive enough to be recorded were generally from the major cities and often became professionals not only in wrestling, but in boxing as well. A few of these sometime amateurs, mostly from Eastern Canada, provide examples of others of the time period.

Gustave (or Edras) Lambert of St. Guillaume was listed unofficially as the collar-and-elbow champion of Eastern Canada, but he had been raised in Connecticut. [EN19] Lambert was not only a wrestler, but in the fashion of the time also fought bare-knuckle fistfights. In one such encounter, in Hartford in the 1880s, he was reported to have won a bare-knuckle match for the prize of 500 quarts of gin! [EN20] In any event, he was a highly regarded wrestler, and his disposition of first prize goes unrecorded.

Another amateur wrestler of that period was Eugene Tremblay of Chicoutimi. Like most wrestlers not in the top professional ranks, Tremblay was a small man. He was reported to have won the world lightweight championship in the years 1904-1907. [EN21] Tremblay beat George Bothner in 1907 in two out of three falls, and Kent lists Bothner as the greatest of American lightweight wrestlers, but makes no mention of Tremblay, the man who defeated him. [EN22]

In British Columbia, a James Lafell (rather an ironic name for a wrestler) was said to be Canadian champion (although there had never been a championship held in Canada). In July 1877, he was challenged by an American, John McMahon. Lafell was reported to be a foot taller and 100 pounds heavier than McMahon but, nonetheless, he lost his self-proclaimed title in two out of three falls.

Another "Canadian champion," this time of "mixed wrestling" (i.e., various styles) was Duncan C. Ross of Cobourg, Ontario. Ross, supposedly the police chief of Cobourg, had been given his title by the flamboyant editor of the Police Gazette, Richard Fox, to stir up sporting interest. This Canadian pseudo-champion was challenged in 1882 by Bill Muldoon, a Yankee from Vermont. Muldoon claimed he could drop Ross six times in an hour for $200. He did. [EN23]

It is confusing, however, to find that a Duncan C. Ross (could there have been two?) hailing from Cleveland, Ohio, used this challenge while in Toronto:

I do hereby challenge any wrestler in Ohio to wrestle me a mixed wrestle, best of three in five falls, to take place in this city before Sunday next, the same to be governed by the "Police Gazette" rules for any amount the party may see fit to name. [EN24]

Also, a Duncan C. Ross turns up in a book by C. Donaldson called Men of Muscle in which he is listed as one of Scotland's outstanding athletes. [EN25] Finally, Webster, in his book Scottish Highland Games, mentions a Duncan C. Ross of Kentucky who was "champion of the world" in the early 1890s but who lost at Aberdeen to one George Johnston in a catch-as-catch-can contest. [EN25]

Adrien Richard from L'Islet was an outstanding Canadian wrestler at the turn of the century. Richard, known as "l'homme caoutchouc" or "rubberman," won the Canadian title (no weight indicated) in 1904, only to lose the title on a technicality. He had competed against professionals and that was enough to rule him ineligible. [EN26] (The Amateur Athletic Union of Canada was formed in 1883 to legislate on such matters. [EN27] Their workload must have been light, indeed.)

Very gradually, as the country grew in population and sophistication, came the emergence of amateur wrestling. In the period from about 1890 to 1914, several significant things occurred which helped to shape the future of amateur wrestling in Canada. These included:

Amateur wrestling did not blossom suddenly for any one reason, but rather, matured slowly from all these influences.

The YMCA, which subsequently had a significant impact, did not, at first, embrace the mat game. An international contest between the Toronto and Buffalo YMCAs at the turn of the century had events ranging from the rope climb to the potato race, but no wrestling. [EN28] The assault-at-arms at the University of Toronto included fencing, rifle drill, and bayonet drill, but not wrestling. [EN29] In 1888, the Montreal Amateur Athletic Association listed six clubs in its affiliation including gymnastics and drama, but not wrestling. [EN29]

Gradually, however, it was introduced in universities and clubs. All leading nineteenth century universities in Canada were founded by Scots immigrants - McGill, Toronto, Queens. And the Scots brought their long athletic traditions with them. [EN30]

In 1901, the Argonaut Rowing Club sponsored the first Canadian amateur wrestling championships at Mutual Street Arena in Toronto, and at that time published the country's first amateur rules. This was a significant step in legitimizing amateur wrestling, and, although the entries were anything but overwhelming, the first championship in 1901 was considered to be a success. The fans, however, were a little upset at the brevity of the matches. Having grown accustomed to the professional three of five falls (or even best of eleven) and at least an hour of wrestling, they were chagrined at the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) ruling whereby a single fall decided a match. In fact, the feature bout at 145 pounds between J.E. Meyer of Rochester, New York, and Fred Nielson of West End YMCA ended in 2:45 with Nielson the victor on a hip toss.

The winners of this first championship were:

115 lbs. A. Edwards, National Baseball Club125 lbs. No entry

135 lbs. E. Meanwell, Rochester Athletic Club

145 lbs. F. Nielson, West End YMCA [EN31]

In short, there were four weight classes but only three were contested.

In the universities, wrestling had generally started on an intramural basis. At Queens, Col. Cameron introduced wrestling in a room under the Medical School's dissecting laboratory. With an interesting choice of words considering the location of the gym, one report states that "Specimens of wrestling were given by the instructor. The instructor undertook to wrestle any two men in the room and the way the students were tossed about was ludicrous." [EN32]

At the University of Toronto in 1900, a diploma course was offered in gymnastics and physical drill. One of the activities in which the men were trained was wrestling. [EN33]

The University of Alberta played a significant role in the development of amateur wrestling in Edmonton. The Wrestling and Boxing Club, which was organized during the first term of 1911-1912, proved to be a dominant factor. [EN34] Other universities introduced the sport in similar fashion but usually wrestling was included as one item in something called The Assault-at-Arms. This association for wrestling lasted until at least 1940. [EN35] The assault-at-arms featured items such as bayonet drill, tug-of-war, and fencing, and reflected the military origins of physical education and sport in this country. [EN36] As early as 1909, the assault-at-arms had been streamlined to three events: boxing, fencing, and wrestling in what was known as the Canadian Intercollegiate Athletic Union (CIAU). This association involved McGill, Queens, Royal Military College, Ottawa, Trinity, Toronto, and McMaster. [EN37] For the first three years, Queens dominated the intercollegiate competition. [EN38] At the second annual CIAU Assault-at-Arms, held at Queens in 1908, there were only three weight classes. The results from this competition were:

Lightweight T.E. BrunetMiddleweight J.B. Saint

Heavyweight J.A. McDonald

And while Queens was hosting the intercollegiate wrestling, the Montreal Amateur Athletic Association, which finally formed a wrestling club in 1906, [EN39] hosted what was claimed to be the first Canadian championships in 1908. This championship was held under the auspices of the Amateur Athletic Federation of Canada (notice "federation" not "union"). There were 33 entries for the inaugural contest within six weight classes. Anyone over 158 pounds was considered to be a heavyweight. The results were as follows:

| 105 lbs. | Lacasse |

| 115 lbs. | A. Coté |

| 125 lbs. | M. St. Denis |

| 135 lbs. | No entry |

| 145 lbs | A. Bain |

| 158 & Hvywt. | J. Geoffrion |

It was reported that, "The bouts in the 158 pound class aroused the spectators to such a ptich of excitement that hardly a man was able to keep his chair." [EN39]

It may be interesting to digress here to show what place amateur wrestling actually held in the culture of Canadian society. The Montreal Amateur Athletic Association, for example, had several clubs formed under its leadership. To publicize them, to raise funds, and to recognize or honour the performers, a public demonstration called a "smoker" was held. Wrestling at the Montreal AAA was taught by George Smith. Tuesday and Friday were given to instruction; Wednesday, to a workout. When the wrestlers were deemed ready to perform in public, the smoker was arranged in conjunction with other member clubs at the Montreal AAA (not with other wrestling clubs because there was virtually no outside competition).

A typical athletic smoker sponsored by the Montreal AAA boxing and wrestling clubs held on December 16, 1911, contained the following program:

Overture Alexander's Ragtime BandWrestling Mitchell vs. Prest

Boxing Binmore vs. St. Pierre

Wrestling Nelson vs. Hunter

Song Mr. Wm. Davidson

Boxing Paton vs. McKay

Song Mr. H. Hamilton

Boxing Savage vs. Williams

Boxing Roberts vs. McBrearty

Song Mr. W. Weldon

Wrestling Hingson vs. Smeaton

Music MAAA Mandolin Club

Boxing Dakin vs. McMurray

Song Mr. W. Davidson

Boxing Art Ross vs. Bill Armstrong

Song Mr. C. Weldon

Boxing Watt vs. Rosenbloom [EN40]

Bouts were held between club members only. In fact, no one but club members and sponsored friends were allowed to attend the smoker, otherwise the event would have been in violation of the city by-laws against boxing.

In the schools other than universities, there was little recreational activity. In fact, education itself was not considered particularly important and establishing schools led to conflict. Schooling was seen to be an upper-class privilege that was opposed by the less wealthy settlers. [EN41] Private schools, such as Ridley, Upper Canada College, and Trinity, imported English schoolmasters and with them, English sports such as cricket. Thus, it would have appeared to the predominantly lower class settlers that the class distinction some of them had fled and all had suffered under were to be imposed on them in a new country.

The private schools flourished nonetheless, and supported athletics for the purposes of moral training and character building. The English traditions and ideals were imported with the English sports. [EN42] The games, of course, were the traditional English school sports and did not include wrestling. It would seem that despite the support wrestling received from influential people such as Sir Thomas Parkyns and the Marquis of Queensbury, the sport was stigmatized by its association in some places and some times with tavern brawls, bull-baiting, and similar low-level activities of the peasant class. While boxing eventually gained the title of "the manly art of self-defense," wrestling was held to be a sport for churls. [EN43]

Despite the stigma, despite the absence of wrestling in the upper class schools, despite the dearth of highly organized competitions, or of coaches and facilities, wrestling as a sport managed to survive. It can be surmised that much more wrestling took place in this country than was ever recorded. Given the fact that the only media of the time, the newspapers, would give coverage to activities of the upper classes only, it is possible that wrestling was more vital than accounts of the time would indicate. Many historical documents and books make brief and passing comments indicating that the sport took place at barn raisings, fairs, weddings, and similar gatherings. Since these accounts were written by the rare individuals who were literate among early settlers, they tended to focus upon aspects of the culture important to people of that class - the economics, and the politics of the time, and not the peasant pastimes of the dirt farmer.

Gradually, however, other sports were introduced into the curriculae of private schools and some wrestling was included among the non-traditional sports. There is no indication of the type of wrestling nor whether there were interschool competitions. [EN44]

In the public schools meanwhile, poor standards, poor facilities, and under-trained teachers were the norm. Education was taken under sufferance so there obviously was no thought (or resources) directed to physical education or sports. In contrast, in the U.S. over 1,000 high schools supported wrestling teams by 1900 and 46 Eastern colleges (including the Ivy League) fielded teams. [EN45]

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the YMCA came into the picture. Whereas the YMCA was not initially supportive of athletics, shortly after the turn of the century when "muscular Christianity" became popular in North America, it was one of the few places where wrestling was encouraged. By 1902, the YMCA in Canada, partly due to the influence of J. Howard Crocker, was allied with the Amateur Athletic Union of Canada. [EN46]

In 1909 at the YMCA in Winnipeg, 30 men regularly met for wrestling. [EN47] Crocker, who had been a major factor in changing the anti-physical nature of the YMCA, also was the manager of Canada's first properly organized Olympic team assembled for the 1908 Olympics in London. Ross reported that a goodly portion of this team was made up of YMCA members. [EN48] Canada's first entry in Olympic wrestling, Aubert Coté of Montreal, although not a YMCA member, but a Montreal Amateur Athletic Association member, was surely influenced in 1908 by Crocker's evangelical enthusiasm for sports.

The picture of Canadian wrestling as World War I clouded the horizon was encouraging. The enormous influx of settlers from 1903-1914 not only gave wrestling a broader base (as it did to all sports), but it brought in some experienced competitors, with foreign birth and upbringing, who contributed largely to Canada's national wrestling teams. In fact, that influence can be seen even today. Canada has had a long legacy of top-flight wrestlers born and/or trained out of the country who have represented her internationally. In addition to this influx, other factors favoured a surge in wrestling participation in the amateur ranks. The Olympics became more important from 1904 through to the first World War, and education also played a more significant role in general life. Athletics, including wrestling, began to permeate society.

EN1. C.M. Wilson, The Magnificent Scufflers (Brattleboro, VT: Stephen Green Press, 1959), 76; see also Edmond Desbonnet, Les Rois de la Lutte (Paris: Berger-Levrault & Cie., 1910).

EN2. G.A. Kent, A Pictorial History of Wrestling (Toronto: Spring Books, 1960), 125.

EN3. D. Webster, Scottish Highland Games (Edinburgh: Reprographia, 1973), 85.

EN4. Toronto Daily News, April 6, 1901.

EN5. Toronto Daily News, April 9, 1901.

EN6. Victoria Daily Colonist, November 24, 25, 1888.

EN7. Toronto Globe, July 1, 1883.

EN10. B. Weider, Louis Cyr (Montreal: Beauchemin, 1958), 147.

EN11. Montreal Gazette, September 28, 1876.

EN13. Montreal Gazette, September 20, 1843.

EN15. "Perspective," La Presse, 18:28 (July 10, 1976).

EN16. S. Davidson. "History of Sports and Games in Eastern Canada Prior to World War I," unpublished doctoral thesis, Columbia University, 1951, 22.

EN17. S. Fregault, Canadian Society in the French Regime (Ottawa: Canadian Historical Association, No. 3, 1954), 6.

EN20. Toronto Daily News, March 28, 1901.

EN21.E.Z. Massicotte, Athletes Canadiens-Française (Montreal: Beauchemin, 1909), 178.

EN26. Toronto Globe, June 1, 1882.

EN27. C. Donaldson, Men of Muscle (Glasgow: Carter & Pratt, 1901), 31.

EN30. G. Redmond, The Sporting Scots of Canada (Toronto: University Press, 1982), 197.

EN31. Toronto Daily News, February 14, 1901.

EN32. Toronto Daily News, March 18, 1901.

EN33. Athletic Leaves, 1:1 (September 1888).

EN34. Redmond, 1982, ix; Webster, 1973, 25.

EN35. Toronto Daily News, March 21, 1901.

EN36. Toronto Daily News, April 12, 1901.

EN37. D.D. Calvin, Queens University at Kingston 1841-1941 (Kingston: Queens University, 1941), 279.

EN38. F. Cosentino and A.A. Howell, A History of Physical Education in Canada (Toronto: General Publishing, 1970), 30.

EN39. J. Barry, "An Attitude Survey of Wrestling Involvement, Satisfaction, and Discontinuity among Active and Non-Active Wrestlers and Contributors," unpublished master's thesis, University of Alberta, 1979.

EN40. T.A. Reed, The Blue and White (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1944), 232.

EN41. R. Moriarty. Organizational History of the Canadian Inter-Collegiate Athletic Union Central (C.I.A.U.C.) 1906-1955. Unpublished doctoral thesis, Ohio State University, 1971.

EN45. Montreal Star, March 21, 1908.

EN46. Montreal Star, April 23, 1908.

EN47. Montreal Star, December 16, 1911.

EN48. G. Watson, "The Founding and Major Features of the Sport and Games in the Little Big Four Canadian Private Schools," CAHPER, 40:1 (September 1973), 28-29.

EN49. A. Metcalfe. "Some Background Influences on Nineteenth Century Canadian Sport and Physical Education," CJPSPS, 5:1 (May 1974).

EN50. Wilson, 1959, 55; Badminton Library (London: Longmans Green, 1897), 182.

EN53. E.L. Johnson, The History of YMCA Physical Education (New York: Follet Publishing Co., 1979), 83; see also David I. Macleod, Building Character in the American Boy: The Boy Scouts, YMCA, and Their Forerunners, 1870-1920 (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1983).

EN54. M. Ross, The YMCA in Canada (Toronto: Ryerson Press, 1951), 189.

For further information on British regional wrestling styles, please see:

http://www.the-exiles.org/essay/histwreseng.htm

Donald Walker's "Defensive Exercises" (1840), including chapters on Cumberland/Westmoreland and Cornish-Breton wrestling is available at: http://schoolofarms.tripod.com/DefensiveExercises/

An article on early Cornish wrestling may be viewed at: http://ejmas.com/jwma/jwmaart_pfrenger_0300.htm

For comprehensive information on the wrestling career of Dan McLeod, including his matches with the Canadian strongman Louis Cyr, please see: http://iclah.com/sports/wrestling/mcleod/tmcleod.htm

An overview of early American wrestling is available at: http://www.wrestlinghalloffame.org/history/wrestlinginusa.htm

For background information on the 19th century Olympic movement , please see: http://www.hickoksports.com/history/ol19thc.shtml

A comprehensive history of the YMCA movement is available at: http://www.ymca.net/about/cont/history.htm