***

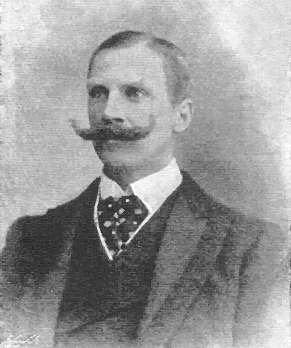

Yukio Tani, 4-dan. Copyright © 2000 The Budokwai, all rights reserved. See also http://www.budokwai.org/1tanigreats.jpg and http://www.budokwai.org/Tanialbhall.jpg

Copyright © Graham Noble 2000. All rights reserved. An earlier version of this article appeared in Warriors Dreams, volume 1. Reprinted by courtesy of Graham Noble.

***

Yukio Tani, 4-dan. Copyright © 2000 The Budokwai, all rights reserved. See also http://www.budokwai.org/1tanigreats.jpg and http://www.budokwai.org/Tanialbhall.jpg

Yukio Tani was never too good with dates, and even the one date he did quote -- September 26, 1899, when he and his brother arrived in London at the invitation of Edward W. Barton-Wright -- was wrong. Richard Bowen has established that the two came to Britain in September 1900, and were followed not long after by S. Yamamoto. Yukio Tani was to stay in England for the rest of his life, but his brother and Yamamoto returned to Japan within a year, possibly due to a disagreement on the use of jujutsu as "entertainment."

When Barton-Wright gave his lecture before the Japan Society of London in 1901 he took along Tani and Yamamoto to demonstrate jujutsu technique. The three men showed the throws and locks of the art and then Yamamoto performed what seems to have been pretty much a standard feat among many of those early jujutsu pioneers. He lay on his back with his hands tied and had a pole placed against his throat. Three men on either side of the pole held it down while two stood on Yamamoto and another two held his legs in position. At a signal these ten men pressed down to prevent Yamamoto moving, but within twenty seconds he had escaped the holds and was a free man.

E.W. Barton-Wright, ca. 1900

At the same lecture Barton-Wright gave a demonstration of "locking" on a volunteer from the audience, the six-foot tall Lt. Douglas. "The lecturer," the report read, "a much smaller man than his opponent with the greatest of ease threw him down and in a variety of practical performances illustrated the modes of obtaining victory." [EN1]

Barton-Wright set up a school of arms with his Japanese instructors. It didn't attract a great deal of interest. Sadakazu Uyenishi's student William E. Garrud thought this was probably because of large entrance and instruction fees. But whatever the reason, the venture failed.

At this, Tani split with Barton-Wright and then went into the music halls under the management of William Bankier (the strongman Apollo). In the world of the music hall strongman and wrestler, with its challenges and counter challenges that meant he had to be able to prove his art against any opponent. But Tani had been ready to meet all comers from his first days in England. Bankier had first met Tani at Barton-Wright's school and tested him on the mat. He later wrote, "As Tani stands only 5 foot in height, the task before me seemed a particularly light one. To my astonishment however, he had me at his mercy in less than two minutes. How it was accomplished I did not know, but there I lay at the end of the bout, completely tied up with the Jap grinning from ear to ear and laughingly asking me if I had had enough?"

Bankier induced some of the top professional wrestlers of the day to visit Barton-Wright's school. The group included Jack Carkeek (the self-styled "King of Wrestlers"), Antonio Pierri, and the former English national champion Tom Cannon, but none of these big guns could be persuaded to have a bout with Tani. A wrestler called Collins did go to the mat however and within a minute he was thrown heavily, falling outside the mat and on the stone floor. "Being a little stunned," wrote Bankier, "he was unable to renew the contest."

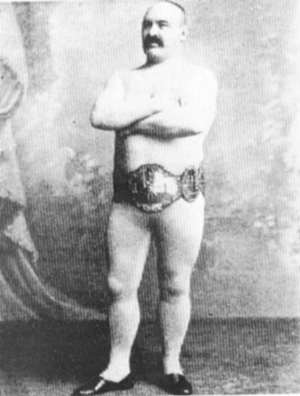

Tom Cannon, 1890s

There is a long list of wrestlers who tried conclusions with Yukio Tani -- but, note, under jujutsu rules with which they were unfamiliar -- and they all seem to have succumbed to a stranglehold or armlock.

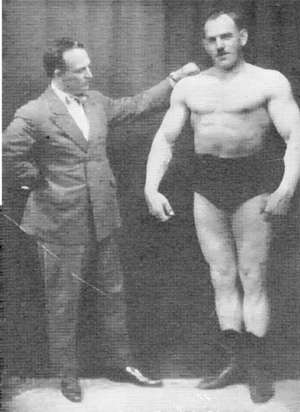

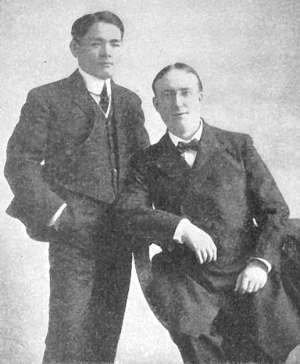

Tromp Van Diggellen, left, shows off his "Monarch of Strength," Herman Gorner

In his autobiography Worthwhile Journey, the South African wrestler and strongman Tromp Van Diggellen recalled:

When he came to London, he did his training at the Apollo Saldo club in Great Newport Street, where at times I did my own training. Bill Klein, the able instructor and masseur who was employed by Monte Saldo, told me that [world heavyweight champion George] Hackenschmidt had refused to have a bout with Tani saying that he might strain a muscle and so be incapacitated for the music hall exhibitions he gave nightly.

To amuse the habitues of the famous club I agreed to have a contest with the wiry Jap. First we wrestled, and Tani was very fair and made no attempt to use his jujutsu locks. In a couple of minutes I had him pinned flat on his back. This had been expected of me and so I laughingly donned the special canvas jacket that one wears when indulging in the art of ju-jutsu. Seventeen seconds later I was not smiling, but choking, while I tapped the mat as quickly as I could. The Jap had neatly tripped me as I applied a hold to his jacket. I hit the mat and before I could spring to my feet, his two feet were at my neck, choking me. The feet were naked and all my strength failed to pull them apart. Not only strength but some peculiar knack was in that hold.

I tried once more, but as I seized Tani's canvas jacket he fell backwards, a foot was applied to my abdomen and I sailed through the air as he hit the mat with his back. Again I had no chance of getting away, and again those sinewy feet held me by the neck and more strongly than any man's hands could! This time only fifteen seconds had elapsed before I was choking and tapping the mat with both hands [i.e., signalling submission] as fast as I could. As I walked off with my arms over the shoulders of the little 'Yellow Peril' I asked him if he really was the Japanese champion. 'No, no,' came the reply. 'That is only publicity talk. In Japan I am only third rate. The great champions are amateurs and they never give public shows of our art. To the masters of ju-jutsu, our science is almost a religion.'

Percy Longhurst was one of England's leading writers on wrestling, and he too recalled those early demonstrations. "I have a very lively recollection of the first exposition of the science given to the public," Longhurst wrote.

His view changed after he had gone on the mat with the Japanese, and he wrote about this in Health and Strength in January 1902, at a time when the art was still being presented as Barton-Wright's "Bartitsu." [EN2] In a three-page article called "Bartitsu and European Wrestling," Longhurst wrote:

Of course, I was in both encounters handicapped to a certain extent. The Jap knew perfectly well what he was going to do, while I did not, and I was by no means sure what I was going to do either. It is not easy to reproduce exactly 'in play' the sort of attack against which Bartitsu claims to be -- and is -- so effective a defence: a most aggressive sort of defence, too, which aims at disabling one's adversary. I had some idea of the principles of the game and knew that even if I did succeed in throwing my opponent to the ground, it did not follow that I had got the better of him. On the contrary, in many instances the absolute reverse would be the case. By the mere nature of the styles of wrestling with which I am acquainted, my endeavours could be solely directed to the throwing of my opponent to the ground, whereas his energies were being used for a far wider object; consequently I was placed at a disadvantage. The use, too, of the jacket -- the loose, short coat which both of us wore -- did not come easy to me, although in Bartitsu it is a factor of the highest importance; and my knowledge of wrestling did not enable me to offer a successful defence against the tactics of my opponent. I must admit too, that some of the most punishing and disabling tricks were, with a charitableness which I fully appreciate, not made use of by the Japanese.

Like other wrestlers and strong men performing in the halls, Tani and

Bankier had to offer a public challenge, and for the record it read (from

Sporting Life, December 1904):

MILE END ROAD E.

TO-NITE TO-NITE TO-NITE

Special Engagement of Apollo's Wonderful

Japanese Wrestler

YUKIO TANI

£100 to any man who can defeat him. Notwithstanding the physical disadvantages against heavier men (for Tani weighs 9 stone only), Apollo will pay any living man twenty guineas who Tani fails to defeat in fifteen minutes: Professional champion wrestlers specially invited. To induce amateurs to try their skill, Apollo will present a magnificent silver cup, value 40 guineas (supplied by Mappin Brothers) to the one who Tani fails to defeat. The amateur making the best show will receive a valuable gold medal. All entries must be received each evening before the contests.

I don't know exactly when Tani joined with Bankier to begin his years-long odyssey through the music halls and theatres of Great Britain, but by 1903 he was a well-known figure to the public. Said Health and Strength in December 1903: "Yukio Tani the clever Japanese wrestler, has lately been appearing at the Tivoli music hall, Leeds. His offer of twenty guineas to anyone whom he fails to defeat in fifteen minutes, brought him before the best wrestlers from Lancashire and Yorkshire, but the twenty guineas still stands to Tani's account. In several quarters the Jap's methods are not considered orthodox, according to the British system of wrestling. Acton, the well known Lancashire wrestler, met defeat in 7-1/2 minutes."

Newspaper coverage of music hall wrestling of those days was pretty good, so if we look through the files of, say, The Sportsman and pick out a typical edition such as December 10, 1907, we can read a short notice of Tani's performance at the Chelsea Palace the previous night.

He paid his shilling entrance fee to the music hall that night and sat impatiently through the various acts, "the knockabout comedians, the pretty dancers and the acrobat," until at last Tani's turn came. He began by giving a demonstration with an assistant of the various throws and locks of jujutsu, but interestingly Peter Parkey "knew all of these by heart, as I had read Raku." The latter was of course a reference to Sadakazu Uyenishi's Text Book of Ju-Jutsu as Practised in Japan.

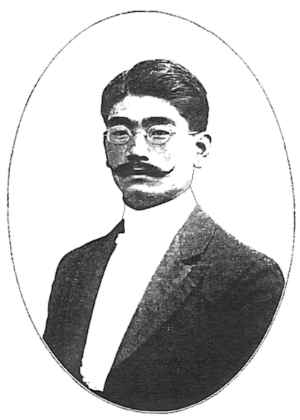

Sadakazu ("Raku") Uyenishi, from The Text Book of Ju-Jutsu as Practised in Japan (London: Athletic Publications, 1905).

After that, a powerful young wrestler, well known locally, came up to accept Tani's challenge.

He could hear the audience shouting encouragement, "like those distant voices you hear sometimes when you are just on the boundary of dreamland." He heard the timekeeper shout, "Three minutes." After a scramble on the floor he found himself again facing Tani, who stood there calm and smiling, waiting for him to attack.

Several people (including myself) have written that no one ever won prize money. Not so! The Budokwai's quarterly Judo of July 1950 carried a letter correcting a claim made for Tani by one of his pupils, novelist Shaw Desmond. Mr. George Lorn, from a Liverpool judo club, wrote that: "There are still living ex-catch wrestlers who took prize money of £5 for lasting three minutes with the deceased champion. One resides in Wigan still who took £25 for lasting five minutes." That is interesting, although I have problems with the amounts and the times quoted, since they disagree with the printed terms of Tani's challenges. Maybe some of those old-time wrestlers were exaggerating their exploits. Anyway, Mr. Horn went on to say, "We in the North, particularly miners, dales and fells men, as catch men find many of the 'chips' and 'hanks' similar throws. A clever catch man of the old school was a delight to watch with his slickness -- Yukio Tani is well remembered 'Up North' for his fighting spirit and well respected."

Going through the old sporting newspapers and magazines you might occasionally find accounts of men staying the fifteen-minute distance with Tani (but not defeating him). A Lancashire lightweight wrestler called Bobbie Bickell went the required distance, as did the Scottish heavyweight Alec Monro. Monro weighed around 15 stone (210 pounds) and was well known as a professional wrestler. He stood up against Tani for fifteen minutes at the Glasgow Coliseum, then dashed over to Kilmarnock on the same night where he also stayed fifteen minutes with another top Japanese, Taro Miyake. Miyake seemed a bit upset about this and challenged Munro to a rematch, undertaking to defeat him in thirty minutes or forfeit £40. (Health and Strength, February 6, 1909.) If the rematch did take place, however, it was not reported in later issues of the magazine.

Yukio Tani had a lot of success against professional wrestlers, although these bouts might sometimes be rough as the wrestlers tried, not only to win the prize, but also to save themselves from defeat at the hands of a much smaller foreigner. The rules of fair play might occasionally break down, as they did in Tani's contest against the well-known Tom Connors at the Free Trade Hall in Manchester. Immediately following the customary handshake Connors attacked Tani, intending to lift him up bodily and dash him to the ground with all his strength. Tani however swung out of the hold -- and both men went over into the orchestra pit. As they remounted the stage Connors struck Tani with his fist, a foul for which the audience booed him. When they came to grips again Tani took hold of Connors by the collar of his jacket, brought him down on top of himself and secured a strangle hold. Connors lost his temper and again struck Tani with his fist. The referees were about to disqualify him when he succumbed to Tani's hold. [Probably ryote jime, "two-hand choke".] Total time, 1 minute, 55 seconds. Connors left the stage to a chorus of booing.

In its report of the Tani/Miyake match of December 1904, The Sporting Life referred to an earlier bout between Tani and wrestler Joe Carroll at the Empress Theatre, Brixton. Tani seems to have lost this one under controversial circumstances: "On that occasion two of his [Tani's] teeth were sent down his throat, and he walked off the stage and refused to wrestle any more. Joe was asked to meet him the following evening, but, although the Englishman was present, his [Japanese] rival did not turn up."

Nevertheless, Tani's success against wrestlers led him to challenge such famous heavyweights as the Indian Gama, when he was in London in 1910, and for a period of years, George Hackenschmidt, the biggest name in turn of the century professional wrestling.

***

In retrospect, the early propagators of jujutsu in Britain were fortunate in their timing. During the late nineteenth and early twentieth century Japan had emerged as a major world power and victories in wars with China in 1895 and Russia ten years later aroused international admiration for the "plucky little Jap". In addition, efforts to launch the art coincided with a vogue for physical culture and professional wrestling. This was, in the view of many writers, the golden age of professional wrestling, a period, which lasted from around 1898 to 1913, and the retirement of the then "world" champion Frank Gotch.

It was a golden age, in a way, with names that are still remembered today -- Hackenschmidt, Zbyszko, Gotch, Gama, Padoubny. But here were probably few genuine contests, or "shoots." I believe the big tournaments on the Continent and America were "worked" (prearranged), and in Britain professional wrestling was largely a creature of the music hall and theatre. Still, bearing that in mind, there were some good wrestlers and strong athletes in those days.

George Hackenschmidt, the "Russian Lion", was born in Estonia in 1878. He was a terrific natural athlete and strongman who, at an early age, was taken in hand by the famous St. Petersburg authority on physical culture, Dr. V. von Krajewski. Hackenschmidt won the Russian weightlifting championship in 1898 but by then his interest in wrestling was beginning to take precedence over weightlifting: in the World Weightlifting Championships held in Vienna in 1898 he took third place in weightlifting but first place in the wrestling tournament that took place at the same time.

George Hackenschmidt, the Russian Lion, about 1905

From then on Hackenschimdt embarked on a career as a professional wrestler. The level of interest in wrestling can be gauged by the list of tournaments he entered (and mostly won) during the next few years:

Hackenschmidt came to Britain in 1902, and after defeating the top men, established himself as the greatest wrestler of the day. After a couple of years he switched his wrestling from the Greco-Roman (actually French, but the Germans didn't like that name) style used on the Continent, in which no holds below the waist were allowed, to the freer, more versatile British catch-as-catch-can style.

The early 1900s were a time of great enthusiasm for wrestling matches in Britain and Hackenschmidt's contests against opponents such as Pierri the Greek and Madrali "The Terrible Turk" created intense excitement. The sportswriter Norman Clark recalled, "I don't think it any exaggeration to say that Hackenschmidt's matches with Madrali and others at Olympia and the Albert Hall created popular excitement such as no form of athletic contest has ever surpassed in this country."

In fact, over the years, Hackenschmidt's contests against big-name opponents do not seem to have been all that frequent. His main source of income came from his appearances on the music halls, and like the jujutsu men he would offer prizes to anyone who could stay fifteen minutes with him without being pinned. When he first arrived he appeared at the Tivoli in London and broke the box office record. As a result his fee was raised to £150 a week, which was really something for an athlete in those days, but the Tivoli audiences soon lost interest in the way he simply overpowered his opponents in two or three minutes.

Hackenschmidt was rather a modest and serious person, not really a flamboyant show business type. But he gradually learned to hold back and add a little showmanship in order not to lose any bookings. And he acquired considerable popularity through his music hall appearances.

A challenge to the great Hackenschmidt must have seemed like a natural progression for Yukio Tani. Still, the hand of his manager, William Bankier, can be seen in all this.

Bankier was a well-known strongman who appeared under the name Apollo, and in the strongman world of that era challenges always seemed to be flying about the pages of the sporting papers and physical culture journals. Bankier had a particular bee in his bonnet about Eugen Sandow, the most famous of the old-time strongmen. For example, this appeared in the Glasgow Evening Times on March 6, 1899:

Eugen Sandow, ca. 1900

No matter, what is important is that challenges were a feature of the day, used to whip up publicity, and just as part of a rivalry to secure bookings and to be billed as "The World's Strongest Man" (there were numerous of these), "The World Wrestling Champion", the "World Champion Club Swinger", the world champion anything. So, while Tani and Bankier's challenge to Hackenschmidt was thus a publicity ploy, it was also a fairly seriously thought out matter.

A hundred pounds was deposited by Bankier with The Sporting Life to try and secure a match, and at the conclusion of Hackenschmidt's match with Antonio Pierri in November 1903, both Bankier and Tani jumped on the stage and repeated the challenge in front of a crowd of 3,000 people.

Throughout all this Hackenschmidt kept mum. He was making his way as the top man in the game and Yukio Tani was an irritation he could do without. Hackenschmidt probably never believed for a moment that Tani could beat him in any form of contest. But there was always the off chance, no matter how slight, that the "jolly little Jap" could apply one of his clever oriental tricks and win the contest. And apparently this was a risk that Hackenschmidt was not prepared to take.

When he started out, Hackenschmidt was ready to meet anyone in a wrestling match. In fact, he made his name in Britain by jumping on the stage and accepting the challenge of Jack Carkeek, the self-styled "King of Wrestlers," and during the next two or three years he established himself as Britain's top star in pro wrestling. But then he gradually seemed to grow, not soft, but a little complacent and increasingly cautious.

In an article published in Health and Strength in 1909, responding to questions about his recent lack of competitive matches against other top pros (Frank Gotch and John Lemm in particular), Hackenschmidt wrote:

Quite a number of people seem to fancy that a professional boxer or wrestler should always be willing to accommodate any rival who wishes to challenge him, without the slightest regard for his present or future career. They conveniently forget that a professional wrestler or boxer is quite as much a business man as any tradesman or professional in any other calling, whether it be law, medicine, engineering, music or architecture.

Wrestling is my business and I have always tried to conduct it in a business like fashion. I am certainly very fond of the sporting element which enters into it, but should be absurdly careless if I allowed my tastes in that direction to interfere too seriously with my career in life.

John Lemm, the Swiss Mountaineer

So Tani was a bad business risk. Hackenschmidt's reputation and drawing power was based on a long undefeated run of matches. If he met Tani and won, that would represent just another in the series. But if he lost, his reputation would be badly tarnished. Viewed this way, there was no reason why he should step outside wrestling and engage in a mixed style match.

It's hard to imagine a man less than 9 stone, however skilled, beating

a 15 stone wrestling champion -- and Hackenschmidt was a real powerhouse.

The report of the match with the American champion Tom Jenkins in New York

in 1905 stated that "Jenkins was handled like a pigmy in the hands of a

giant. Hackenschmidt broke holds as if they were the clutchings of children."

Yet William Bankier knew the sporting and physical culture world inside out. If he made the challenge, then he must have felt that Tani's technique and knowledge of leverage would nullify Hackenschmidt's tremendous advantages in size and strength.

Bankier had trained with Tani, and although a strongman himself he could never get the better of the Japanese. Although Bankier may not always be a reliable witness, in his book Jujitsu: What It Really Is, he noted that Tani always kept tricks up his sleeve and never taught the full extent of his knowledge. On one occasion the two men bet "a sumptuous dinner" on whether or not Bankier could last 15 minutes with Tani in a contest. "The match came off at once," wrote Bankier, "and sad to relate, after all my practise he beat me in exactly three minutes with a hold I had never seen him use. It was then that I found out that he keeps a good deal of knowledge in reserve for emergencies."

Hackenschmidt did offer twice to wrestle Tani in the Greco-Roman style, but that was ridiculous. If Tani and Bankier managed to arrange a match they would be sure it was under jujutsu rules, with which Hackenschmidt was totally unfamiliar. In the book he wrote in 1909, The Complete Science of Wrestling, Hackenschmidt recommended the study of jujutsu trips and throws for all wrestlers. In 1903, however, when Tani issued his challenge, Hackenschmidt had no knowledge of jujutsu technique and in fact was still wrestling mainly in the Greco-Roman style, a form which requires strength and endurance but is limited in its technical range. (Hackenschmidt only switched fully to the catch-as-catch-can style with his 1905 contest against Tom Jenkins.) Tani, however, had a lot of success in matches, using his own rules, against wrestlers, some of them top names. Thomas Inch wrote how the well-known Maurice Deriaz tried to win Tani's £25 by staying 15 minutes with him. In some ways Deriaz was a slightly smaller version of Hackenschmidt (5'4-1/2" and around 190 lbs. against 5'9" and 210-220 lbs.) and a top wrestler and weightlifter on the Continent. Yet he failed to make the 15 minutes. According to Inch, "The small Jap won fairly easily and Deriaz put up with some severe punishment before he collapsed, though he lasted very nearly to the time limit."

So who knows? You could argue either way. You could say that Hackenschmidt's size, strength, and wrestling ability would have been too much for Tani. Over in France the jujutsu teacher Regnier challenged Ivan Padoubny, the Greco-Roman heavyweight wrestling champion, but found Padoubny's physical advantages just too great. And you can jump forward ninety years and make an argument for Tani on the basis of Royce Gracie's victories in the early Ultimate Fighting Championship® (UFC) contests.

Gracie, you will recall, was the Brazilian jujutsuka who beat much larger opponents, including wrestlers Ken Shamrock and Dan Severn. That's not to say it was always easy. In the Severn match, Severn seemed to dominate the action without, however, having the technique to finish off Gracie. So after a struggle of fifteen minutes Royce was able to apply a sankaku-jime, meaning a triangular leg choke, and make Dan tap out. That defeat was largely due to Severn's lack of experience in submission fighting. Wrestlers seek to establish dominance by pinning their opponent on his back, but that result means absolutely nothing in jujutsu. In fact, it only allows the jujutsu man opportunities to apply locks and strangleholds. So, while Hackenschmidt was a wrestler through and through, it was always possible that he might get caught by one of those moves and be defeated.

Well, it was all a very long time ago, and it doesn't matter now. A Tani-Hackenschmidt match would have been a minor sensation, but it never happened. And, a hundred years later the "Which style is best?" argument has moved on. Both men were top-class performers and we will just have to leave it at that.

***

When Gunji Koizumi founded the London judo club known as the Budokwai in January 1918, Yukio Tani was member number 14, and much of his free time was spent at the dojo. Therefore he helped form the first generation of British judoka.

Gunji Koizumi in Holland, November 1949. Copyright © 2000 The Budokwai, all rights reserved. See also http://www.budokwai.org/1gkgreats.jpg

Pupils received individual instruction, which meant that Tani would often be on the mat for four or five hours at a time. In person he was friendly and cheerful, but on the mat he was a strict taskmaster. One of his pupils, Marcus Kaye, wrote: "Throughout all his instruction there ran a steadfast devotion to the realities of judo, with a corresponding avoidance of anything flashy, unsound, or easy."

Tani was a man who believed in learning by doing, and students remembered the effects of his throws, particularly his hane-goshi [a spinning hip throw]. But it was in groundwork where his real skill was felt.

At Barton-Wright's lecture to the Japan Society of London in 1901, given just after Tani arrived in London, the quality of his groundwork was noted against the much heavier Yamamoto. Richard Bowen, the historian of British judo, picked up an echo of Tani's skill when he did randori with Len Hunt, a veteran British judoka, during the late 1940s and early 1950s. Hunt had started training with Uyenishi's student William Garrud during the 1920s before moving over to Tani and the Budokwai. Dicky Bowen told me that "Hunt, in his mid-seventies, could even deal with some of the young internationals on the ground -- it was Tani's groundwork. It was astonishing. I mean, I'm a former international and he just tied me in knots when he was in his late sixties or early seventies."

We know little about Tani's early training. Apparently his father and grandfather were teachers of jujutsu and he started training at a young age. So this must have been around 1890. Shingo Ohgami told me that Tani trained with Fusen-ryu groundwork specialists Torajiro Tanabe and/or Matauemon Tanabe. This is supported by information in Takao Marushima's Maeda Itsuyo: Conte Koma (1997), where it is said that Matauemon Tanabe was a friend of Tani's father. This is interesting because the latter Tanabe, the fourth headmaster of the Fusen-ryu, features in the early history of Kodokan judo.

In the September 1952 edition of Henri Plée's Revue Judo Kodokan, Kainan Shimomura, 8-dan, wrote:

Straightaway Tanabe sought the combat on the ground, but Tobari succeeded in remaining standing up. After a fierce fight Tanabe won by a very successful stranglehold on the ground. Tobari, bitterly disappointed by the defeat, began to feverishly study groundwork.

The year after, he challenged Tanabe again. This time it was a ground battle and once more Tanabe won. He was now famous and, in the name of the ancient schools, challenged the members of the Kodokan, and even Isogai (then 3rd dan, at the time of his death he was a 10th dan) was put in danger from his ground technique. The Kodokan then concluded that a really competent judoka must possess not only a good standing technique but good ground technique as well. This is the origin of the celebrated 'ne-waza of the Kansai region'. And in conclusion to all this one may very well say that Mataemon Tanabe, too, unconsciously contributed towards the perfecting of the judo of the Kodokan.

When he practised ground work with a student his method was to pick a weakness and work on it. Trevor Leggett, the late British judoka, recalled that his neck was relatively weak when he began his own study of judo. So Tani would take him to the ground and apply a stranglehold, then release it just as he was about to tap. Leggett would begin to fight back and then the hold would go on again. This was repeated time after time. Leggett wrote (Judo, July 1955):

So in the terms of jujutsu or judo the competitive level was not high. Yukio Tani may have paid the price for that when he faced Taro Miyake at the Tivoli theatre in December 1904 and was repeatedly thrown, although the much heavier Miyake would always have beaten him anyway.

For the record, Tani did win a "World Championship" contest against another Japanese, Katsukuma Higashi. [EN3] The match took place at Bostock's Hippodrome in Paris on November 30, 1905. Tani was clearly the superior jujutsu man, but the contest ended unsatisfactorily after two minutes when the fighters went to the ground and Tani's foot caught Higashi in the groin. (The latter had to be taken to the hospital.) [EN4] But it was a meaningless title, and Tani himself probably knew it. Even the Health and Strength report of the match (January 1, 1906) noted "that Tani proved himself to be the better of the two would appear to render the alleged championship at stake to be somewhat of a farcical nature. For there are two other Jap wrestlers now in this country both of whom are admittedly his superiors; and it is more than probable that there are better exponents of the science than any we have seen who have never hitherto quitted their native islands."

Katsukuma Higashi and H. Irving Hancock, from the frontispiece of The Complete Kano Jiu-Jitsu (London: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1924)

In a rather angry letter to Health and Strength in 1909, Taro Miyake, a one-time colleague who had fallen out with Tani, wrote that there were "thousands" of judoka in Japan who could defeat him. In the first 1913 edition of the famous book The Fighting Spirit of Japan (these lines were deleted from later editions), E.J. Harrison wrote: "The West already knows what can be done even by second and third rate men. The well known Yukio Tani, for example, who for a long time had everything his own way on the boards in EnglandÖ had no special standing in Tokyo, where scores of young students might have been found to throw him."

Tani himself always admitted that there were many in Japan better than he was. In fact, in all the material I have looked at I cannot find any reference to him exaggerating his abilities or boasting about his exploits. If it is any indication, in 1920 when he and Gunji Koizumi affiliated with the Kodokan, Jigoro Kano awarded him a second-dan in judo, but you feel he would have been a real strong second-dan. His "Jujutsu World Championship" in 1905 may not have meant anything, but in 1904 he did beat Jimmy Mellor in a £100 match for the lightweight wrestling championship, catch-as-catch-can style.

Mellor was Britain's best lightweight, and claimed the world's championship. So this victory was a terrific performance by Tani, as the newspapers of the time recognised. The Sporting Life praised "a thoroughly genuine sporting match," and then going on to say, "The little Jap showed what a wonder he is by beating the Englishman at his own game. Two falls to one was the decision, though the fall given against Tani was questioned by many.

Probably quite a few of the Japanese who came to Britain to be wrestlers during the early 1900s, men such as Uyenishi, Miyake, Ohno, and Maeda, were better judoka than Tani, yet they never attained his popularity with the public. It's easy to forget, but Tani was only around 5 feet tall and weighed just 9 stones, and when he first arrived in England he was only nineteen years old. Yet almost straightaway he was thrown into the world of music hall challenges. He stayed true to his art, but he also had to make it work in a strange and turbulent environment. So, although other Japanese may have had greater ability, they could never match his impact.

And his years on the stage never made him soft or complacent; he remained a martial artist all the way through. "One evening [during the early 1930s] I had a slight headache and decided to leave the dojo early," Trevor Leggett remembered. "Mr. Tani noticing me asked what was the matter. I told him and said that I would come on Wednesday, the next practice night. 'If a man comes to rob you on the street,' he said, 'can you say you have a headache and ask him to come back on Wednesday?' I never left early after that."

Tani was only in his fifties and still training vigorously when he was crippled by a paralytic stroke. That was in 1936, and for such a man it must have been heartbreaking. But he never seemed to show any self-pity. His days on the mat were over but he still tried to attend the dojo when he could and the well-known judo teacher Eric Dominy recalled, "He sat in his chair by the side of the mat and discussed and criticised my judo with me, and encouraged me." Tani also attended the Budokwai annual shows right up to 1949.

This great budoka died on January 24, 1950.

ENDNOTES

EN1. E. W. Barton-Wright, "Ju-jitsu and Ju-dô," Transactions and Proceedings of the Japan Society, 5, 1902.

EN2. For details of Bartitsu, see Graham Noble, "An Introduction to W. Barton-Wright (1860-1951) and the Eclectic Art of Bartitsu," Journal of Asian Martial Arts, 8:2, 1999, 50-61; E.W. Barton-Wright, "Self-defence with a Walking-stick: The Different Methods of Defending Oneself with a Walking-Stick or Umbrella when Attacked under Unequal Conditions," Pearsonís Magazine, 11 (January 1901); reprinted at http://ejmas.com/jnc/jncframe.htm; and E. W. Barton-Wright, "Self-defence with a Walking-stick, Part II." Pearsonís Magazine, 11 (February 1901); reprinted at http://ejmas.com/jnc/jncframe.htm. If the name sounds oddly familiar, you're thinking of Sherlock Holmes, who, in "The Adventure of the Empty House," claimed of "baritsu [sic], or the Japanese system of wrestling." See Richard Bowen, "Further Lessons in Baritsu," The Ritual (Bi-annual Review of the Northern Musgraves Sherlock Holmes Society), 20, Autumn 1997, 22-26.

EN3. Higashi began his professional wrestling career in New York City, where he became the subject of articles and books by Irving Hancock and Robert Edgren. See, for example, H. Irving Hancock and Katsukuma Higashi, The Complete Kano Jiu-jitsu (New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1924) and Robert Edgren, "The Fearful Art of Jiujitsu," http://ejmas.com/jcs/jcsart_edgren1_0300.htm. Higashi's style, by the way, was not Kodokan judo but Tsutsumi Hozan Ryu jujutsu.

EN4. While George Bothner spent the next fifty years telling journalists and students alike about his match with Higashi, the Tani-Higashi match is not nearly as well-documented. Therefore the following are some details of the Tani-Higashi match from contemporary sources.

From Sporting Life, November 24, 1905.

In our usual notes concerning 'Sport on the Continent,' we published on Wednesday last some particulars of the Japanese wrestler, Katsu-Kuma Higashi, who, recently, in the columns of the 'Sporting Life,' issued a challenge to the world. As might have been expected, Yukio Tani, the famous exponent of the ju-jitsu style of wrestling, took up the challenge, and attempted to bring off a match with Higashi on Tuesday evening at Bostock's Hippodrome Paris, where the new champion of the Japanese style [Higashi] is now meeting all comers.

Higashi, however, refused to wrestle Tani without due notice, and the meeting of the pair is postponed. In all likelihood the match will come off to-morrow.

Late last evening our Special Correspondent, 'Jupiter', telegraphed to the effect that Mr. Bostock had deposited with him the sum of £100 to bind a match between Higashi and Yukio Tani. It therefore now only remains for the wonderful little Jap to cover Higashi's money. We shall, no doubt, shortly be able to announce that this has been done, and that the match is definitely arranged.

(From our Special Correspondent.) Paris, Friday evening.

A challenge from Higashi to Yukio Tani and [Taro] Miyaki [sic] to wrestle in the ju-jitsu style, appeared in the 'Sporting Life' of November 16. No notice was taken of it, but Yukio Tani and his friends invaded the stage at Bostock's Paris Hippodrome on Tuesday last, and wanted then and there to put up a contest between Higashi and Tani. The aspirant to European honours, Higashi, simply came forward and said, 'When we Japs challenge in ju-jitsu it is to a finish, or must it be confessed, death. I will wrestle him to death, at once.' Thereupon Yukio Tani and his friends hung back, and wanted to wrestle for love.

On Wednesday evening I received a wire from Bostock. 'Please come up to-night.' I went, and was publicly handed the sum of £100, and with these words, '"Jupiter," correspondent of the "Sporting Life," we deposit £100, and are willing to meet Yukio Tani or Miyaki for all they can put up.'

Tani is still waiting, but he cannot wait for ever. He is willing to meet the 'champion of the world' at any moment, barring only the dim and distant future; and to deposit his stakes the moment a reasonable day is offered for the contest.

/s/ M. Allerdale Grainger, 305, Oxford-street, Oxford Circus, London, W., November 24, 1905.

From Sporting Life, December 2, 1905.

Paris, Dec. 1

A house such as that which Bostock's Hippodrome held last evening has never been seen in Paris. The result of the match, which was for £100 a side to a finish, was disappointing, for at the end of two and a half minutes all was over.

The officials were M. Bruneau de Laberie, Dr. Jacque Liouville, Dr. Luis J. Phelan, and Mr. Britten.

Before the match Mr. Bostock addressed the spectators, and explained that the match was for the sum named, but above all, for the jiu jitsu championship of the world It was decided before the contest that, if deemed necessary, a rest of five minutes should be allowed at the end of each fifteen minutes. It was forbidden to put the fingers in the eyes or punch with the fists.

Higashi got the grip on Tani at once, and the pair rolled over and over. Some splendid holds were put on and broken away from by each party, but after 2 min. 28 sec. had elapsed, Tani gripped his rival and compelled him to surrender. Higashi was examined by Doctor Saqui, who was understood to say that the beaten man could not go on, and the contest thus ended somewhat tamely. -- Jupiter.

The following statement, which we received signed by four gentlemen who witnessed the Tani-Higashi jiu-jitsu contest in Paris on Thursday last, will be read with interest. These four gentlemen -- Messrs M. Allerdale Grainger, Hugo W. Simon, Arnold Foster, and R. Verner -- were in a good position to see all that occurred, and they assert that no foul hold, such as has been suggested, was used by Tani. The injuries sustained by Higashi are to be explained by the fact that Higashi gripped Tani so tightly between the thighs that the later, in his endeavours to extricate himself, possibly inflicted them with his head. In the face of this evidence it will at once be seen that Tani could not possibly have gripped Higashi in the manner stated. The statement referred to is as follows: --

Soon after our arrival at the Hippodrome our party was informed of the choice of M. le docteur Liouville as president of the contest. We were much pleased to have in that capacity a man of such honourable position among Parisian sportsmen. The following conditions for the encounter were agreed upon by Messrs. Tani and Higashi, and by everybody concerned: -- (1) No attack upon the eyes by fingers. (2) No twisting or bending of fingers. (3) No kicking. (4) No hitting. (5) No attack on genital organs. (6) No 'gouging' or gruelling with the knuckles. It was also agreed that after fifteen minutes indecisive struggle a repose of five minutes would be allowed. Dr. Phelan was appointed timekeeper.

Dr. Liouville then took his seat as president, the match was announced by Mr. Bostock, and the above conditions categorically repeated to the audience. The combatants then advanced to the attack. After some manoeuvring for a grip, Higashi was either thrown or else let himself be thrown, and it seemed as if he were desirous of fighting the matter out on the ground rather than on his feet. Tani came down immediately, somewhat over him, in a temporary hold-down position, at his side. Tani then passed into a straddling position across Higashi's body, and began the usual neck-lock feint and attack. Higashi upset him, and after some complicated work both men rose to their feet. Tani was not long in throwing Higashi again. The throw was so easy that it may be that Higashi was willing to be thrown. In this style of ju-jitsu a man endeavours to throw his opponent unawares, in order to profit by the momentary surprise of the latter, and secure the advantage of position on the ground. On the other hand, a man may give his opponent an opponent an opportunity to throw him, so that, falling in a manner foreseen by himself, and for which he is ready, he may secure the advantage of position. Therefore no stress need be laid on the fact that Higashi was thrown a second time; let it be noted merely that he made no effort to throw Tani, and that he fell easily to Tani's attack, apparently recognising the latter's superiority standing up.

We may pass over the struggle following the second throw, until the moment when Higashi, with his back on the ground, snapped Tani's head between his legs, and so secured a not very effective leg squeeze on Tani's neck. The leg squeeze is a hold that may amount to a lock with a novice at ju-jitsu. It is particularly effective when the squeeze on the neck is given by the hard bones of the inside of the knees. In this case Tani's head was well up between Higashi's thighs, and the squeeze on the neck, although severe, was by no means serious. Higashi at this moment was lying on his back, holding Tani's head between his thighs, his hands clasped round Tani's body, which was lying over him, with the feet projecting over his head. Tani forced his arms round Higashi's waist, and succeeded in rising to his feet, bearing Higashi with him, the latter still leg-squeezing his neck and holding his body. Higashi was then hanging upside down, and Tani had his arms clasped around his body.

Tani now withdrew his arms from their clasp around Higashi's body, and in order to free his head from the leg squeeze, pushed upwards on Higashi's thighs. With this purchase he was enabled to screw his head down and out from between Higashi's legs. The pressure during this screwing out was such that the skin of Tani's nose was discoloured. At this point a movement of protest was made by one of Higashi's friends, but evidently nothing irregular had occurred, as the movement was immediately discouraged and suppressed by several prominent gentlemen on the stage, and the contest continued uninterrupted for some considerable time. After some vigorous struggling, in which the adversaries rolled themselves and one another over and over -- sometimes one, sometimes the other being on top -- Tani began a definite attack on the neck. In the usual manner he secured a deep hold on Higashi's collar with one hand, got a fair grip with the other, and then, at this moment when his equilibrium was naturally insecure, was upset by Higashi, who came over on top, only to find that he had rolled between Tani's legs. Tani was now able to improve his grip of the neck until both hands were at the required depth on either side of Higashi's neck. At the same time he had brought first one foot up and then the other, and placed them on Higashi's legs just above the knees.

This was the decisive moment. Suddenly pushing away one of Higashi's knees, and pushing up on the other thigh, he upset Higashi, came over on top of him, and bent down to the final pressure of the neck lock. Higashi surrendered, and walked off the stage. It was then, and not till then, that the surprising allegation was made that Tani had gripped Higashi in a vital part with his hands while freeing himself from the leg-squeeze described above. This allegation was flatly denied by Tani, and by witnesses whose eyes are accustomed to follow the intricacies of ju-jitsu contests. Practised eyes intent on the two struggling figures saw absolutely nothing of the unusual movement which would have been necessary for the alleged act, a fact of some importance when it is remembered that this is the first contest that has taken place in Paris between two skilled exponents of ju-jitsu, and that nearly all of those present were assisting at such a spectacle for the first time.

After some discussion it was agreed that a meeting should take place the next day (Friday), that Higashi's injuries (if any) should then be ascertained by medical examination, and a judgement if possible arrived at. In view of this arrangement, one was astounded to hear the stage manager, meanwhile, informing the audience that it had been decided that Higashi had been disabled by a foul blow. Tani's protests at this outrage were drowned by the orchestra, but the feeling of the audience was clearly indicated by their applause as he advanced protesting to the footlights.

To sum up, we assert that it is absolutely untrue that a foul was committed, and that if, as Higashi asserts, he has sustained any injury, it was caused by the frantic pressure he himself was exerting on Tani's head, when the latter was between his knees.