Introduction

When I had originally wrote the paper, Kinesiology of Fencing and Kendo, it was written as a result of an assignment for a Kinesiology (Biomechanics of Physical Activity) course at Eastern Michigan University, while I was working on a second bachelors in physical education (kinesiology), my original degree is in physiology.

I wanted to compare the kinetic relationship between two different sports and two techniques that are similar in action and results. The intent of the assignment was to analyze the mechanics of a specific technique of a sport. I decided out of my own interest to compare two similar techniques from two similar sports. Both lunging and shomen uchi both involve the movement of a weapon by pushing the body forward towards an opponent using the legs (lower torso), while at the same time moving the weapon’s point or edge using the arms (upper torso).

The purpose of the paper was to explain the techniques in scientific terms. Kinesiology is the science of movement. The movement of the body is dictated by the laws of physics. The advantage to learning how the body moves could result in a better understanding of the basic physics of the body, which could translate into improved techniques and methods of training.

There are two explanations for these sports: a traditional explanation and a scientific explanation. Historically fencing has been explained using scientific terms since the Renaissance; these developments came about because of improvements in the military and the medical sciences. Of course my descriptions are based on my own scientific observations and my personal experience as a fencer, as a fencing instructor and as a kendoka. I hope with this paper I can make some clarification and delve deeper into the subject of kinesiology.

Discussion

Kinesiology as defined by the School of Kinesiology at the University of Michigan (2013), as, “the study of human movement.”

In the book, Introduction to Kinesiology (2013) by Shirl J. Hoffman (Ed.), kinesiology is defined as, “…Knowledge derived from: (1) experiencing physical activity, (2) engaging in scholar study of physical activity, (3) conducting professional practice centered on physical activity.”

Understanding kinesiology allows for an athlete to focus on which muscle groups to train. Both the lunge and shomen uchi are explosive actions which originate from the feet and legs. An example of exercises that could improve this could be power lifting, such as squats, clean and jerk or the dead lift. The idea would be to develop power in the lower torso. Similar to a sprinter that is looking to gain as much ground as possible, off the first step.

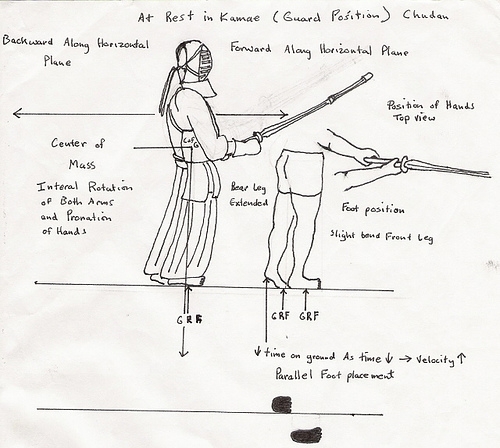

Figure 1.

According to Quinlan (2008):

Center of mass / Center of motion is in the “Koshi” (hips). The term Koshi refers to more than just what we normally refer to as “hips”, but hips will serve for the discussion. It is often told that the source of motion must be from your hips. As one Sensei explained to me, “if you were to draw a line one the side of your hips and the front, the point at which they meet (inside of you) is your center of motion and where you balance yourself.” The above shows the center of mass well up into the torso. In Kendo, I believe our center of gravity is much lower than depicted. Perhaps this is simply picking-nits on the artwork? Comments? (Quinlan, 2008).

In Figure 1. Center of mass is referring to the solar plexus region of the body. If the body was divided by equal weight that would be the center of mass. In males more weight is located in the upper torso and for females in the hips. According to the Physics Factbook, (Elert, 2006), Elert pointed out that the center of mass is just below the belly button and for females it is lower than males. In my paper, I never discussed the center of motion.

Defining the center of mass requires the definition of mass, which is “ … a fundamental property of the object; a numerical measure of its inertia; a fundamental measure of the amount of matter” from the site HyperPhyiscs Project, by the author, Carl Rod Nave (2000), Department of Physics and Astronomy, George State University. For the majority of men and the majority of women, the center of mass for man is in the upper torso, the chest, arms and abdomen (the core) and for a women it is in the lower torso (abdomen, hips and legs). The reason for this is that the muscles are dense. Gravity is pulling on the body, the place with the greatest amount of mass per volume will determine where gravity is pulling the most.

Center of mass impacts inertia, which is explained from Newton’s first law of motion, from his Principia (1687), translated from Latin, “Everybody continues in its state of rest, or of uniform motion in a straight line, unless it is compelled to change that state by forces impressed upon it.” In order to move the body, you move your mass. Unfortunately, gravity wants to keep you in the same place, and you have to balance that mass, otherwise you would fall down.

There is a theory in fencing, in order to score a touch (a point) requires that the first person who initiates an action, scores, for example, during an attack, the attack starts with the movement of the edge of the blade or point of the weapon towards the opponent, and if the opponent counter-attacks (he does not parry) and the person who initiated touches first, the theory is that, the inertia of the initial attack even upon death would penetrate the opponent, therefore the initiator’s attack would be counted as a touch or point. So the speed of the attack does not determine who scores, but the momentum or the inertia of weapon does.

In fencing, controlling your inertia controls every aspect of your lunge. You can control the speed and timing of the touch, and the amount of force used. Also there is a little known effect, that once the lead leg lands, the body keeps moving forward, sliding a few inches and in some case a few feet, which for a shorter person can help close the distance.

In kendo, knowing how to control your inertia can impact when you start your attack or when to counter attack. It also impacts your follow through and knowing when to stop and start another attack. If the center of gravity or mass is in the upper body, which is in the case with most male kendoka, the problem would be, your lower body has to catch up.

More mass equals more inertia. This is concern that some people might fall down after running forward during an attack because they cannot control their inertia. Of course, for a man if he increases his leg mass by footwork and weight training this helps. osing weight can also be beneficial. Adipose tissue contributes little to kinetic energy, only muscle does this. In addition, muscles can be controlled versus adipose tissue which is going along for the ride.

According to Quinlan (2008) he stated that:

I am unsure of the meaning of the abbreviation GRF in the diagram. Nor do I understand the caption: “ (arrow down) time on ground. As time (arrow down, arrow right) velocity (arrow up)”. This caption points to the left (rear) foot. A quick parse could be “Decrease/low time on ground. As time decrease/lowers, forward velocity increases.” Comments? (Quinlan, 2008).

For clarification below are definitions of the terms for the different figures.

Figure 1. Definition of terms:

Center of Mass – The balance point of an object's mass (Elert, 2006).

Distance – A measurement between two points.

Extension – Straightening of a limb.

GRG – Ground reaction forces.

Horizontal Plane – The ground.

Internal Rotation of Arms – The rotation of the arms towards the midline from the anatomical position.

Parallel – Side by side.

Pronation – From the anatomical position the palms are facing up.

Rest – No movement or motion.

Time - A measurement of repetition of a cycle of motion (seconds).

Velocity – Distance/time (meters/seconds).

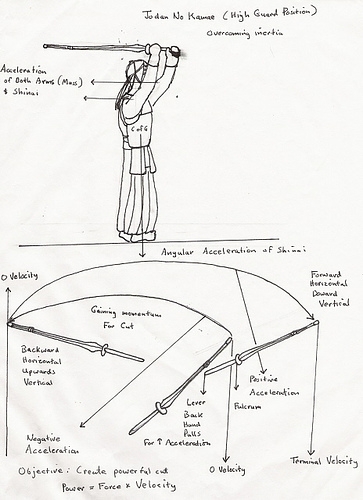

Figure 2. Definition of terms:

Acceleration – A change in velocity over time.

Angular acceleration – Change in angular velocity (Newton’s Second Law of Rotational Motion) (Bloomfield, 1992).

Fulcrum – A pivot point.

Inertia – A property of matter by which it remains at rest or in uniform motion in the same straight line unless acted upon by some outside force. (Newton’s First Law of motion) (Bloomfield, 1992).

Lever – An object which a force is exerted which produces torque about a pivot (Bloomfield, 1992).

Power – Force multiplied by velocity.

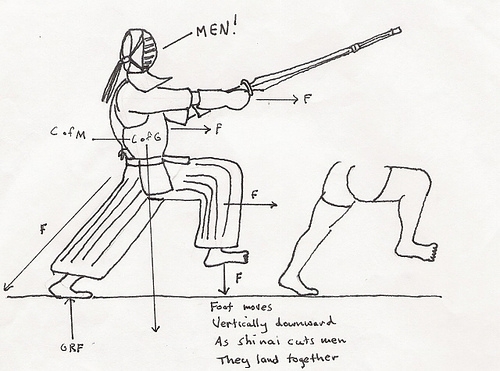

Figure 3. Definition of terms:

Vertical – To move up or down.

Downward – In a down direction.

GRF or ground reaction forces, which is defined as, “the ground reaction force is equal in magnitude and opposite in direction to the force that the body exerts on the supporting surface through the foot. (Thompson, 2002). Newton’s third law of motion, “for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction” (Newton, 1687).

Regardless of which sport you are talking about either fencing or kendo, the actions of legs are needed in order to propel the body forward. Our bodies are always falling down towards the ground. Whether it is with a lunge or with shomen uchi, the body (meaning from the bottom of your feet to the top of your heads) is being pulled down by gravity As you push off of the ground, the ground reacts by pushing against you. With both lunging and shomen uchi, to reach the opponent both quickly and with force requires the pushing of one leg, while lifting the other leg.

Basically, it is very similar to walking, where our feet are pushing off the ground at all times. One foot lifts off the ground, swings forward, while the other foot pushes against the ground, as the foot lands, you stop, shift weight and swing the other foot in the same direction. The objective in fencing and in kendo is reaching opponent with the edge or the point of the weapon while at the same time keeping the body of the upper torso as far away as possible. The other advantage is that you can keep a greater distance from the opponent, and you can make up that distance during an attack by taking a large step with one leg. Inertia will keep the body moving forward until the lead leg lands, or you collide into your opponent.

According to Quinlan (2008) he stated that:

When describing weight distribution and the position of the feet in Kamae itself, the article states: “From kamae, or guard position, the shinai is kept in front and the weight is shifted slightly backwards causing the center of mass to shift backwards.

”In Kendo, the weight distribution of the body is usually described as 70% of your weight is on your forward foot, 30% on your rear. Again, described to me by one sensei “Your rear heel is raised slightly off the floor, enough for a couple fingers to fit under and your front foot is flat, but not rooted. You ought to be able to slip a piece of paper under your front heel.” Shifting your posture, balance, center of gravity, etc… to the rear is a classic example of how we create “Suki” (an opening) for our opponent. Comments?

Here are a series of pictures that were taken very recently as I was helping a Kendoka at our club with his posture. His upper body’s weight was toward his rear when in Kamae. I took these pictures to help show the difference. The third picture is the two made of the two original pictures combined with a line drawn down through the center of the hips.

Tilted

posture (weight backwards)

Straight

Posture (weight forward). This was accomplished by a simple pelvic

tilt.

Combination

(weight forward / weight backwards) with centerline. With the

abdominal contraction/pelvic tilt added while assuming kamae, the

hips become aligned with the upper body and the

body’s mass balances properly toward the front.

(Quinlan, 2008).

While at rest, from my original paper, I argued that, “from kamae, or guard position, the shinai is kept in front and the weight is shifted slightly backwards causing the center of mass to shift backwards” (Riddle, 2007).

According to Quinlan (2008), the author stated that:

In Kendo, the weight distribution of the body is usually described as 70% of your weight is on your forward foot, 30% on your rear. Again, described to me by one sensei “Your rear heel is raised slightly off the floor, enough for a couple fingers to fit under and your front foot is flat, but not rooted. You ought to be able to slip a piece of paper under your front heel.”

Weight by definition is the mass of an object attracted by the earth. While standing, gravity is pulling on the body equally in all places. When your sensei stated that you put 70% of your weight on your front foot, what he is really stating is that you are shifting your center of gravity over the front leg, while moving the center of gravity off of the back leg. Of course with your arms extended, while holding the shinai this also shifts the center of mass even more. The argument made was also taught to me when I was learning to fence. However, this is not the case.

To be balanced, in order to move the shinai backwards and then forwards, it would require the center of gravity be under both legs. The power of the Men Uchi comes from the moving of the front leg forward, while moving the back leg backwards, because the shinai does not just move with the arms, but also with the legs. The objective is to get the body moving in a forward direction.

Quinlan is correct about the hips being the center of motion, the combined forces of the front and the back leg generate the kinetic energy to overcome inertia, which starts with frictional forces on the ground, or ground reaction forces, which travels up from the feet, through the leg, to the hips and propels the person forward, and the same principle applies in a fencing lunge.

The reason the heel of the back foot is lifted off the ground has to do with reducing frictional forces and time. Friction generates energy which can be used by the body, but it also can act against you by creating drag. Speed or velocity can be changed by changing distance or changing time. The best way to change how quickly you move is reduce the amount of time doing it. Frictional force acts on the foot, but this can be reduced by changing time. Less contact of the foot on the ground reduces the amount of time applied to the foot. Force equals mass times acceleration (or velocity divided by time). The force of your foot acting on the ground and the ground forces acting on your foot will maximize the force from the foot, while reducing the drag caused by resistance. The front foot does not have this issue because it was lifted off the ground completely.

With that argument, 70% of the center of gravity would be over the front leg, however once the front leg was lifted off the ground, the person would be off balance and falling forward. This however is not the case, because once the front leg lifts off the ground, the center of gravity remains on the back leg. In reality the center of gravity is balanced between the ball of the back foot and the front foot. Ideally, the swinging of the shinai should only make a marginal shift in the center of gravity. Of course what I am suggesting is ideal. People come in all shapes and sizes and this can make a difference in the center of gravity and how one moves, while taking into consideration how much distance one is traveling to reach the opponent.

Based on the images Quilan used, the only thing that he has moved forward is his head. His head is the only thing titled forward. In the over lapping images, it does not show any changes in the body or the center of mass, except for his head.

In a guard position, in fencing, the guard position can be described as a sitting position. If we are standing erect like when you are walking the act of balance is a continuous process. The advantage of a “guard position” is that knees are flexed to lower the center of gravity or center of mass, this improves the balance between both legs, which allows you to focus other part of sparing such as defending or attacking.

According to Quinlan (2008):

The article states “The reason for ki-ai is to cause a compression or contraction of the rib cage by expelling air, this can add to the force from the chest into the weapon.” Again, I must reiterate that I’m not an expert of kinesiology; however this bit seems to be fraught with conflicting information. The “reason” for Kiai is immense, and real Kiai isn’t something that we “turn on or off”…it simply happens. When we train our bodies, we help develop kiai by yelling. Philosophical aspects aside and looking more towards bodily physics, in Kendo our breathing is to come from the abdomen, not the chest. When we exhale, our abdominal and lower back muscles contract, and our diaphragm pushes the air up and out. “Force from the chest into the weapon” seems to imply the tightening or contraction of muscles that we are stressed to keep relaxed. Comments? (Quinlan, 2008).

According to my original paper, I stated that, “the reason for ki-ai is to cause a compression or contraction of the rib cage by expelling air, this can add to the force from the chest into the weapon” (Riddle, 2007). It is true that the abdominal muscles are used in breathing, but ki-ai is a forceful expelling of air, and not just a type of passive breathing.

According to McConnell (2011), in her book, Breather Strong, Perform Better, she stated that:

The rib cage also contains muscles with an expiratory action. These are the internal intercostal muscles, which slope backward; contraction causes the ribs to move downward and inward, similar to the lowering of a bucket handle. Both internal and external intercostal muscles are also involved in flexing and twisting the trunk (McConnell, 2011).

And in the article “What happens When You Breathe?” posted on the National Institute of Health, National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute website, they stated that, “the intercostal muscles between your ribs also help enlarge the chest cavity. They contract to pull your rib cage both upward and outward when you inhale” (NIH, 2012).

According to Quinlan (2008):

When we exhale, our abdominal and lower back muscles contract, and our diaphragm pushes the air up and out. “Force from the chest into the weapon” seems to imply the tightening or contraction of muscles that we are stressed to keep relaxed. Comments?

All of the forces of the legs, arms and body are translated into force into the weapon. And the contraction of the intercostal (both internal and external) while performing a ki-ai is a part of that system.

Figure 2.

According to Quinlan (2008):

The weight of the body is forward in Jodan as for Chudan. The arms and shinai do have an acceleration associated with them when we move them back/up. However, this acceleration is not needed for the cut. Otherwise somebody who begins a cut from the migi or hidari (right or left) Jodan kamae would be weaker compared to one initiated from Chudan, when they ought to be the same. I’m not sure if the author is implying that this acceleration is used for the cut, but this was simply one of the flags that were raised. Comments? (Quinlan, 2008).

The center of gravity will shift some while causing the shinai to move forwards and backwards. Positive and negative acceleration, or an acceleration and deceleration of the shinai. The shinai travels through an arc, which causes the shinai to change in its angular velocity or what is referred to as angular acceleration.

According to Quinlan (2008):

The article states: “Then the shinai is swung forward vertically downwards, and horizontally forwards for maximum acceleration…” “Maximum acceleration” seems to imply that a large amount of speed, and hence muscle usage, is required. The cut is not made due to us “hitting” the target hard or fast, but rather from a “slicing” movement of the blade while in contact with the target. In Kendo, this cutting action is stylized by hitting the target then moving the blade to “slice” via the forward or backward motion of our body. In Iai, the cut does not have to be fast or hard, you must first connect with the target, and then “slice” it via a proper sword swing allowing the blade to do the work. Hitting fast or hard with a shinai or shinken (real sword) does not produce the same results. Comments?

First, let’s define acceleration. Acceleration is a change in distance over a change in time squared.

This translates as the velocity of the object (the shinai) changing over time. This is due to angular acceleration, or the velocity of the shinai traveling through an arc. The variable that impacts this is time. Most people will swing at their maximum acceleration. And the term “hitting” only refers to contacting the opponent. However, to argue that the only the “blade does the work”, is nonsense. The kinetic energy of weapon will be translated into work. Again, the blade is curved to allow for a greater cutting surface, or to allow for more acceleration along the edge of the blade across the body, in other words to increase the work of the blade or the cutting action of the blade against flesh. Force equals mass times acceleration, more acceleration equals more force. That force translates into more kinetic energy which translates into more work on the edge of the blade or a deeper cut.

According to Quinlan (2008):

The article states, “…the same time the shinai comes forward, the foot is accelerated vertically upwards and horizontally forward…” The issue I have here is with the statement “…foot is accelerated vertically upwards…” In Kendo, you do not raise the forward foot vertically as if to “stomp”. Rather, your forward foot stays close to the ground, “skimming” it as much as possible. If your body weight is forward (70/30) it is impossible to simply raise your forward foot vertically; you’d fall over. This vertical motion is only possible if your center of gravity is shifted backward to your rear. Essentially the “70/30” weight distribution gives us forward potential energy which we convert to kinetic energy by initiating a push with our rear foot and extending our forward foot. Shifting our center from any direction other than forward disrupts this process. Yes, there is a vertical component to the motion of our front foot, but it ought to be minimal, i.e., to remove the majority of the static friction between our foot and the floor and allow us to move Comments? (Quinlan, 2008).

What you refer to “skimming” of the ground, I assume you mean that you mean that, the foot is not in contact with the ground, ergo the foot would be lifted vertically upwards. And for some kendoka they do not just skim. And again, if the center of gravity was leaning forward with 70%, as soon the foot was lifted for “skimming”, your body would fall forward. My argument was the leg was lifted and if it was lifted then the center of gravity would be between both legs. The same concept is done with a fleché, but Men Uchi, is closer to a lunge, hence the reason for the comparison.

In Quinlan (2008) he stated that:

More of a technical note that ties in with the above, the classic “Kendo stomp” is not a result of an intentional strong downward force of the front foot on the floor; it is simply a by-product of landing correctly. That’s not to say there is not a lot of force associated with this…there is1. But we do not purposely raise our foot simply to “stomp” downward. It’s much like clapping your hands. You don’t need a lot of force to make the “clap” if you do it properly. If you clap using only your fingertips or the heel of your palm then it’s a different story. This analogy helps describe the “stomp” of the Fumi Komi style footwork. Comments? (Quinlan, 2008).

According Quinlan, he stated that, the ““Kendo stomp” is not a result of an intentional strong downward force of the front foot on the floor, it is simply a by-product of landing correctly,” so the “kendo stomp” is unintentional and therefore not a part of a controlled action, but an uncontrolled action. I could argue, that I could perform the same action correctly, but quietly by controlling my movement of both my legs in order to dampen the sound. In fencing a lunge is a controlled action, hence I can control both my legs individually while attacking, which is a part of the training of a fencer.

According to Quinlan (2008):

Another issue I have is with the labeling of “lever” and “fulcrum” in the above picture. By definition2, “A fulcrum is the support or point of support on which a lever turns in raising or moving something”. By stating that the left hand position is the lever and the right hand position is the fulcrum it would imply that he right hand is center of motion for the cut and that the left hand is pulling or pushing around that center. The labels ought to be reversed with the left hand being considered the fulcrum during Men Uchi. In fact the entire Shinai ought to be considered a “Third Class Lever”3 if my physics memory serves me. Comments? (Quinlan, 2008).

From my understanding, the power applied to the shinai comes from the left hand, while the right hand guides it. In the Eastern Michigan University dojo, as a part of practice, a strengthening exercise involves doing Men Uchi only with the left hand, therefore, the left hand applies the force, which would imply the right is a fulcrum.

In Quinlan (2008) he stated that:

The article states “…and the beginning of the ki-ai or shouting of men to cause more tightening of muscles in the chest and ribs to cause more force or acceleration and therefore cause more power produced during the cut.” Kiai occurs at the moment we strike, not before. It is the by-product of our body acting together with our mind and intent. It is simply “yelling”, not Kiai, if we just make noise at a certain time frame. When you pick up a heavy object, the moment you pick it up and you “grunt” (usually without ourselves realizing it) that is kiai. After you’ve lifted the object, your muscles are tiring, and you make noises while straining, that’s just noise coming from effort. A very subtle but important difference. Secondly I have an issue with the line, “to cause more tightening of muscles in the chest and ribs to cause more force or acceleration and therefore cause more power produced during the cut.” All of this muscular tightening in order to cause more force or more power seems to be flawed. In Kendo, you must keep your upper body relaxed. Tightening of the muscles (especially seen in beginner kendoka) is almost always the source of error in their swing. Staying relaxed and keeping the shoulders low is key to a proper swing. Again, the cut does not come from landing a hard hit. It comes from a coordinated slicing motion of a blade. Comments? (Quinlan, 2008).

Define relaxed? Muscles contract in order to move them. Even in fencing we are told to relax, but what does this mean? It means not to keep a muscle tense all of the time, or holding tension. However, movement of the body requires contracting muscles. In fencing, we are not allowed to “grunt” or make any sounds until the end of a phrase (a complete action i.e. attack). And muscles do tighten or contract forcibly. Kinetic energy is generated from this force.

Figure 3.

According to Quinlan (2008):

The article states “The shinai hits the target, or men, (the head), at the same time the foot lands, this must be done with power, and accelerates downward with the assistance of gravity at 32.2 feet/second squared.” Again, power in so far as hitting hard is not the objective. A “strong” hit is very different from a “hard” hit. In a strong hit, the body is balanced, the shinai and the foot land together along with Kiai (Ki ken tai no ichi: Spirit, Sword, and Body as One). At the moment of impact, tenouchi is used to stop the weapon. This is the only time there is a purposeful tensing of the muscles in the upper body and most of it is in the hands / wrists / forearms. Alignment of the shinai, arms, shoulders, and wrists occurs briefly to add support and balance. This is often referred to as the “wrist snap” in Kendo. The majority of the force from the Kendoka’s strike is in the forward direction. The vertical motion (downward) of the foot is minimal as described above. Comments? (Quinlan, 2008).

Power translates into acceleration and speed. Power has to do with the amount of energy per unit of time. Kinetic energy is the energy used to move an object. These terms “majority” and “minimal” are suspect at best. In fencing we are taught to use force generated by the legs, but to touch softly through controlling our blade work.

In Quinlan (2008) he stated that:

Gravity will have a very negligible effect on the shinai’s motion in the scenario of a shomen uchi. The Shinai’s mass is supported/manipulated by the kendoka’s muscles during the entire motion which are exceedingly more substantial than the downward component of gravity. Gravity would only apply (substantially) in this scenario if we removed our muscular support and allowed the Shinai to “free fall”. Comments? (Quinlan, 2008).

All objects on planet earth are subject to gravity and all objects within the knowledge universe are subject to the laws of physics. If gravity was negligible, it would mean a shinai for a woman and a child would be the same as that for a man. They are different masses, ergo they different weights. Something that has less mass, when the same force is applied, will accelerate faster. An example would be an aluminum bat and a wooden bat, same dimensions, but not the same weight. The aluminum bat will accelerate faster because it has less weight when the same force is applied as that of the wooden bat. Thankfully, all sports have regulated weights and sizes for equipment.

According to Quinlan (2008):

The last issue I have is with the line in the conclusion “It the weapon accelerates this effects the timing of a parry, relative to the distance of the attack.” Acceleration implies an increasing / decreasing velocity. When swinging a shinai, we do not swing faster and faster as we move from overhead toward our target. In fact, a methodical attack with constant velocity will land much more effectively. While speed of attack does affect one’s ability to perform parries, the effect is minimal if proper distance is maintained. Comments? (Quinlan, 2008).

Moving any object through an arc will cause angular momentum or angular acceleration. Changes in time cause changes in acceleration or how quickly you change the velocity. If you are not changing your velocity then you are not accelerating. The velocity along the length of the shinai will be different at different points, therefore the acceleration will be different along the length of shinai. You cannot have a constant velocity moving through an arc or a circle because of changes in distance and time. To swing the shinai, there is an acceleration backwards, then there is a deceleration, then a pause before moving it forward. It is at this point, once the shinai moves forward, the action of the shinai will be telegraphed, therefore affecting the timing of the parry. The closer the attack, the less time an opponent has to react to that attack, assuming you are moving the shinai at the maximum acceleration. With a thrusting weapon, you have linear movement and therefore the velocity can be constant if controlled. .

Hesitating on your attack might cause the opponent to react with a counter attack. And of course, the further way the opponent is at the initiation of an attack such as in the case of Men Uchi, or in the case of an advance lunge, this will give your opponent more time to react to the action. In the case of defense, retreating will also give you more time to parry or avoid being hit, but if this was a real fight, and you want more distance, you could just run away.

Conclusion

I appreciate that Mr. Quinlan made an effort to generate a discussion revolving around the topic of Men Uchi, but with that said, the intent of the original paper was to compare similarities between fencing and kendo techniques. After a long time, I finally was able to invest some time in responding with my own rebuttal to his response to my original paper.

I am hoping that in the future, a further discussion could be made comparing fencing and kendo as closely related sports.

References

Angular acceleration. (2014, March 15). Wikipedia. Retrieved March 18, 2014, from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Angular_acceleration

Bloomfield, L. (1992). How things work: the physics of everyday life. New York: J. Wiley.

Cardall, C., & Daunt, S. J. (n.d.). Newton's Three Laws of Motion. Newton's Three Laws of Motion. Retrieved December 18, 2013, from http://csep10.phys.utk.edu/astr161/lect/history/newton3laws.html

Elert, G. (n.d.). Center of Mass of a Human. Center of Mass of a Human. Retrieved March 18, 2014, from http://hypertextbook.com/facts/2006/centerofmass.shtml

Hoffman, S. J. (2013). Introduction to kinesiology (Fourth ed.). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics Jones, A. Z. (n.d.). Introduction to Newton's Laws of Motion. About.com Physics. Retrieved December 21, 2013, from http://physics.about.com/od/classicalmechanics/a/lawsofmotion_2.htm

Kinetic energy. (2014, March 16). Wikipedia. Retrieved March 18, 2014, from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kinetic_energy

McConnell, A. (2011). Breathe strong, perform better. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Nave, C. R. (2000, August 2). Who is using HyperPhysics?. HyperPhysics Concepts. Retrieved December 21, 2013, from http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/hph.html

Quinlan, S. (2008). Response to a Kinesiology of Fencing and Kendo. Electronic Journal of Martial and Science: Physical Training Journal, 3, 1-2. Retrieved March 18, 2014, from http://www.selectinet.com/go.php?src=ejmas.com

Riddle, J. (2007). Kinesiology of Fencing and Kendo. Electronic Journal of Martial Arts and Sciences: Iaido Journal, 3, 1. Retrieved March 18, 2014, from http://ejmas.com/tin/tinframe.htm

Thompson, D. (2002, April 3). GROUND REACTION FORCE. GROUND REACTION FORCE. Retrieved December 21, 2013, from http://moon.ouhsc.edu/dthompso/gait/kinetics/GRFBKGND.HTM

What is Kinesiology? | U-M School of Kinesiology. (n.d.). What is Kinesiology? | U-M School of Kinesiology. Retrieved December 21, 2013, from http://www.kines.umich.edu/about/what-is-kinesiology

What Happens When You Breathe?. (2012, July 17). NHLBI, NIH. Retrieved March 17, 2014, from https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/hlw/whathappens.html