Kurikara The Sword and the Serpent by

John Maki

Evans

Paperback, 138 pages, published by Blue Snake Books, 2010, Berkley,

California

Review by Daniel Mroz, PhD, University of Ottawa

I happened upon Kurikara in early 2011 while browsing the offerings of my local bookstore. My first impression of the book, that it was both a lean and essential treatment and a volume packed with information, led me to purchase it. Further research into John Evans revealed that he had also written Trog, a long poem evoking his moments of insight and frustration living the life of a martial hermit atop a wild and isolated Japanese mountain. Inspired, I ordered it and discovered a strong, restrained and exact voice. I contacted John Evans, proposing to adapt and direct Trog for the stage. This in turn led to an invitation from Evans to meet and study with him in order to get a deeper sense of the practices that inspired Trog, practices that are described in Kurikara. The review that follows is the result of that meeting…

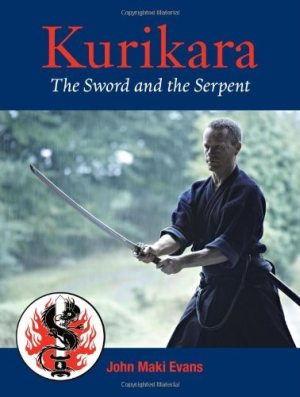

The cover features a picture of the author in chudan kamae and the book is found in the martial arts section of the bookstore but John Evans’ Kurikara The Sword and the Serpent is first and foremost about practices of transformation. Evans’ background and credentials quickly dispel any doubts that this perhaps nebulous goal might inspire in the reader. A disciple of both Battodo founder Nakamura Taisaburo and Chaya Yoga founder Shandor Remete, the precision of Evans’ introductory words on training reveals the quality of the instruction he has received and the depth of his own experience.

Kurikara begins with a specific view of martial practice, one that is based on the Japanese concepts of shugyo, shugendo and mikkyo. Evans’ definition of these terms follows the time-honoured North Asian framework of ‘outer’, ‘inner’ and ‘secret’ levels of training and experience. Describing shugyo in terms of a commitment to personal discipline, shugendo as the path of practice and testing and mikkyo as the inner, personal endeavour to which swordsmanship can ultimately lead, Evans concisely outlines the ground, path and possible fruition of martial training. Evans’ personal memories of key moments in his training accompany each definition and add the weight of narrative and emotion to abstract definition. The title of the book is telling in itself: Kurikara is the name of the double edged straight sword or tsurugi wielded by the Buddhist Tantric deity Fudo Myo O, the ‘unmoving shining king’ whose blade cuts through the knots of compulsive and fixated behaviour.

Having established a view and overall framework, Evans proceeds to lead the reader through a curriculum of methods that he feels is common to all schools of Japanese swordsmanship. I believe I can see the debt this presentation owes to Evans’ teacher Nakamura Taisaburo; Nakamura Ryu swordsmanship is a concise system of recent genesis. While it emerges from tradition, the preoccupation with conservation that runs through older martial arts is deemphasized in favour of cultivating functional skill in drawing, cutting and fencing with the sword. Similarly, even though Evans’ precise descriptions of each phase of training are culturally and historically situated, the reader gains much from the freshness and immediacy Nakamura’s pragmatic orientation brings to the writing.

Chapters one to six take the reader through the incremental stages of Japanese sword practice. Fundamental movements (kihon), pre-arranged movement patterns (kata), conditioning (tanren), striking (uchikomi), cutting (tameshigiri) and sparring (kumitachi) each have a chapter devoted to them. Readers benefit from the accounts of the history and methods of Nakamura Ryu and from Evans’ elaboration of the tanren or conditioning methods he has devised for his students. Evans’ account of practice is economical and focuses on the essential. Readers hoping to discover a detailed training syllabus or extensive presentations of tactical applications will be disappointed. Although each chapter is informative in and of itself, it is the relationships Evans draws between them that make this work stand out as a guide to the process of training martial movement.

The book is organized around the progression of the godai or ‘Five Elements’ of Tantric cosmology and Evans uses this model to describe both the levels of physical skill passed through by the apprentice swordsman and the later internal work of the yogic adept, to which the final chapters are devoted. Building on the body sensitivity described in the chapter on tanren, the student undertakes a regime of mental and physical purification called shinshin renma. The body and mind, cleared of obstacles and compulsions are to be integrated through the practice of sanmitsu yuga. These last chapters describe a synergy of practices derived from Shingon and Tendai Buddhism and Shinto. The use of specific hand and body positions, of ritual chant and of meditation beneath waterfalls is described in terms of their effects on the subtle winds and channels of the body posited by Tantric physiology.

Kurikara concludes with several useful appendices, including an excellent glossary of Japanese, Chinese and Sanskrit terminology.

I am frequently taken aback by Evans’ style, even as his writing enlightens and impresses me. His tone is often so austere and concise that it makes his assertions appear imperious and categorical. Readers used to a more avuncular narrator or a more relativistic style of presentation will have to look beyond the censorious tenor of this text to the modesty of an author who restricts his comments to those things he has himself personally experienced. Those interested in the more personal aspects of Evans’ apprenticeship and practice can turn to an in depth interview with him in Alex Kozma’s fascinating book of martial arts’ conversations Warrior Guards the Mountain.

A more minor criticism is that the romanization of the few Chinese terms in the text is idiosyncratic, employing neither the historical Wade-Giles system nor contemporary Hanyu Pinyin.

To conclude, I find that John Maki Evans’ Kurikara The Sword and the Serpent is an important and inspiring book. It offers a vivid description of martial practices leading to spiritual maturity. It makes no apologies for a perspective that transcends mere cultural exposition, historical contextualization or short-term combat effectiveness. I recommend it with great enthusiasm.

About the Reviewer

Daniel Mroz is an Associate Professor in the Department of Theatre of the University of Ottawa. He is a theatre director and an acting teacher specializing in the physical and vocal training of performers. He holds a PhD in the practice of interdisciplinary arts from the Doctorat en études et pratiques des arts of l'Université du Québec à Montréal.

A student of the Chinese martial arts since 1993, Prof. Mroz is a 20th generation disciple of Chen Taijiquan under Master Chen Zhonghua. He is also a 6th generation practitioner of Cailifoquan, a 4th generation practitioner of Tang Peng Taijiquan and a 3rd generation practitioner of Zhi Neng Qigong under Master Wong Sui Meing (Huang Xiao Ming). He holds an instructor’s diploma in qigong under Master Kenneth S. Cohen with whom he has trained for over a decade.

The Dancing Word, Prof. Mroz’ book on the use of Chinese martial arts and qigong in the training of contemporary stage actors and dancers is published by Rodopi Press. His research and artistic work can be seen at www.dancingword.org.