copyright

© 2010 Douglas Tong, all rights reserved

The following article is the second part of an interview with Såzen Larsen Kusano Sensei of the Sugino branch of Katori Shinto Ryu, which took place in Toronto in July 2010. In this article, Såzen Sensei shares with us his thoughts about the naming of the new dojo. Those interested in learning more about Såzen Sensei can consult his group’s website: http://www.kakudokan.no/

Part Two: Naming A Dojo

Question: The dojo in St. Catharines has been given an official name. Can you tell us about it?

Sensei: Sure, I’ll try to explain it. The dojo name is “Jigan Dojo”.

The dojo name plaque.

JI: The most commonly used meaning is COMPASSION. In a dojo context, this refers to the deeper philosophical meaning of budo, which is not to kill but to preserve life. In other words, our true purpose in budo is not to harm others but to develop our skills. And since the Dojo is a place for developing character and manners, empathy is a paramount value.

GAN: The literal meaning is “EYE”. As practitioners we take a good look at ourselves, and our own conduct, and by introspection we learn who and what we are. But also, as budo-people, we must use observation as a means of learning. We learn by watching. Specifically in actual combat, our life may depend on right observation, meaning just looking at, and carefully observing our opponent. If you recall my talk about the concept of “look-move-respond”.*

DO: The noble path each individual has to walk by himself, and for himself and others equally.

JO: A specific or designated area or place used for practicing and realising one’s path.

Question: Why was it important for the dojo to have a name?

Sensei: Well, most dojos have a name. Even inside a Buddhist monastery, there are many rooms. Several “dojos”, places for study. And it’s not uncommon to have several names. It’s just like in a regular school. There are different classrooms, each with their own classroom number. Example, Room 201, Room 202, etc…

Question: Why are there different names?

Sensei: Because a monastery is basically a school. So for example, if the next lesson in school is chemistry, you would go to the Chemistry Room. Or if the next class is mathematics, you would go to the Mathematics Room. It’s for reference. All these rooms house various and different activities, so they are called “dojos”. And some people get to name them.

Question: So who would get to name a dojo?

Sensei: In modern days, building new monasteries is very rare. But in old times, teachers came by to teach. You see, various monasteries have connections to various teachers. Some are live-in teachers and some are visiting teachers. These are external teachers and they might be an abbot or a priest-scholar from another temple or monastery.

In our history, we have had teachers without a temple. In other words, they are not attached to any one temple. They travel around. It’s not usual but it’s not unheard of either. It’s like in the modern school system, there are some teachers that travel around.*

Sometimes, these teachers would be asked to name a room or dojo. It would be an honour, and the name would last for centuries. And they knew this. So they’d bring out their best brush, best paper, best ink, and would write something really good. Then it’d be mounted and hung according to their traditions.

Question: So, in the case of Dennis Wiens’ dojo?

Sensei: The naming in this case, when Dennis wanted a name for his dojo and if you wanted it in the Japanese tradition, you would naturally consult someone with some knowledge about how to do it. We considered a lot of ideas. It was based a little bit on his personality, how he teaches, his hopes for a place like this, etc…

Question: So, how did you finally decide on those Kanji (Japanese characters) for the dojo name?

Sensei: Putting Japanese characters together is difficult. Finding characters that truly go well together in combination is tough. Like “Ji”. It means compassion and it also means consideration. Part of our training in martial arts is to consider others. For example, I am training with others so it is an important aspect, to think about my partners. And we decided on “Jigan” because we thought about how it is a kendo dojo* and also a Katori Shinto Ryu dojo. And of course, one of our starting positions is seigan (in kendo, chudan).

Yoshio Sugino Sensei performing seigan no kamae (hidari hanmi)

And seigan is also a Buddhist term and the character “gan” in seigan is the same as the character “gan” in Jigan.

Question: Why is “gan” a good word?

Sensei: Let’s go back to “seigan”. You position yourself with a sword. Because kamae means position.*

And seigan is also an old Buddhist term. Sei means “pure”. Gan means “eye”. So seigan is literally “pure eye”. Pure eye has not so much to do with the physical eye but more to do with state of mind. This state of mind is called “pure eye”, meaning “no assumption”, “no preconceived ideas”. So this is a very Zen Buddhist kind of term. Remember, Doug, when old Sugino* started practice, he said… “seigan!”?

Question: Yes, I remember. (Smiling and nodding).

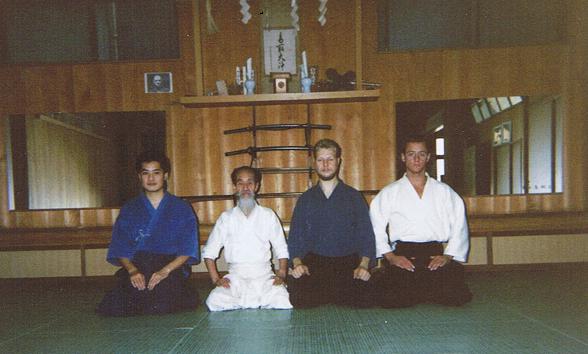

small group photo from 1991-1992 (?) at Sugino Dojo in Kawasaki

(from left to right: D. Tong (the author), Yoshio Sugino sensei, Såzen Sensei, an unknown foreign student)

Sensei: He didn’t say “seigan no kamae”. He said “seigan!” It was no mistake. His meaning was “pure eye”, “observe”, “watch”, “don’t have preconceived ideas”. He was a devoted Buddhist, you know. Students might think “I’ve done this a thousand times!” All these kinds of preconceived ideas. None of those were acceptable.

“Just…now”.

“In this moment”.

That’s what he meant.

I earlier asked Dennis if he would like a Japanese name for his dojo and he said yes, so I promised that I would find one and offered to create one for him.

Question: So, you like this name?

Sensei: Oh, I think it’s a great name. You know, the eye is not a physical eye. We can observe others and we can observe ourselves. In Zen Buddhism, we have a saying:

“We have to turn our eyes and ears inward for introspection.”

Dogen Zenji

Zen Master, 1200-1253

So “eye” is a very good character.

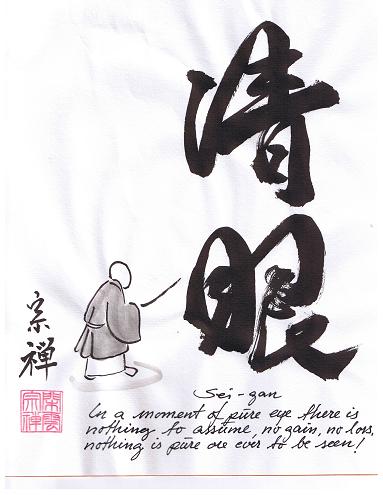

“seigan”

(calligraphy written by Såzen Sensei)

Question: Do you have any final words for our readers?

Sensei: Well, for the fourth year, being invited back to teach and to be invited to do a blessing ceremony has been a wonderful thing. Thank you all. And I hope that this dojo will be a very beautiful dojo and that it will serve people well.

Question: Thank you once again for another great interview.

Sensei: Oh, you’re most welcome. Thank you everyone!

Author’s Post-Script:

Såzen Sensei brings up an interesting point about the monastery being basically a school in olden times. This was certainly the case in Europe, where the only learning in the post-Romanic era resided almost exclusively in the churches:

“According to the Oxford Dictionary, the term ‘dark ages’ was originally applied to the Middle Ages, to denote the intellectual darkness of the times… Public schools had long since ceased to be, and the study of letters was preserved only in monasteries and a few bishops’ households; the enlightened bishops were in most cases themselves monks… Elementary education, where it existed at all, was almost entirely personal – that of the gifted priest teaching his clerk* or a forward boy of his parish.

This simple framework was all that existed – and that only when wars, invasions and human inertia permitted – from 800 till well after A.D. 1000. Monks received what their elders in the monastery had to give; children, whether children sent by their parents to the priest, or oblates taught by their master in the cloister, learnt grammar and psalmody; the fortunate might receive instruction in letters and elementary calculation in the schools of a monastery or a cathedral city; theology was the only ‘advanced’ study, either in the monastery or in the bishop’s familia. There was no higher education north of the Alps, nor any professional class of teachers whether lay or clerical. Clearly, any philosophical activity was out of the question.”

Source: Knowles, David, 1962. The Evolution of Medieval Thought (pp.71-73). New York: Random House.

(The Dark Ages was a “… period of intellectual darkness between the extinguishing of the light of Rome, and the Renaissance or rebirth from the 14th century onwards.” See Dark Ages )

* this same relationship is played out in the famous book The Name of the Rose by Umberto Eco and the brilliant 1986 film by the same name The Name of the Rose starring Sean Connery as the visiting Franciscan friar William of Baskerville sent to investigate a series of mysterious deaths in an isolated abbey in Northern Italy. William is accompanied by his novice Adso of Melk. As a result of the events that transpire during their investigation, Adso learns a lot about life, about education, and about the way the world worked in his time. His final lines are stirring:

“I have never regretted my decision, for I learned from my master much that was wise and good and true. When at last we parted company, he presented me with his eyeglasses. I was still young - he said - but someday they would serve me well. And in fact, I'm wearing them now on my nose as I write these lines. Then he embraced me fondly - like a father - and sent me on my way. I never saw him again, and know not what became of him, but I pray always that God received his soul, and forgave the many little vanities to which he was driven by his intellectual pride. And yet, now that I am an old, old man, I must confess that of all the faces that appear to me out of the past, the one I see most clearly is that of the girl of whom I've never ceased to dream these many long years. She was the only earthly love in my life, yet… I never knew, nor ever learned, her name.”

This mirrors the traditional method of education in martial arts dojos, namely direct oral transmission from teacher to student, master to apprentice. Education is very important and dojos are important in this regard, as places of learning and intellectual (and spiritual) enlightenment. When we practice in a dojo, we need to keep this in mind. It is a place of learning and a place for the cultivation of the soul.

It is not difficult to remember this purpose in dojos for tea ceremony or other such refined arts but we seem to forget this in martial arts dojos. We are not there to beat each other up or show how powerful we are or to quench our desire for combat. We are there to learn, to be educated. Teachers likewise must keep this in mind. For those of us who are teachers, we are there to educate, not to stroke our own ego. We cannot stress enough the importance of “education” in the martial arts. Because without education (technical, yes, but more importantly moral and spiritual education), we are back in the Dark Ages.

Mr. Tong introduced Sugino-style Katori Shinto Ryu to Canada in 1994. His students and his students’ students have gone on to become official members of Sugino Dojo and some have been ranked by Sugino Yukihiro Sensei himself. He can be contacted via email at: doug@dragonfencing.com

The following article is the second part of an interview with Såzen Larsen Kusano Sensei of the Sugino branch of Katori Shinto Ryu, which took place in Toronto in July 2010. In this article, Såzen Sensei shares with us his thoughts about the naming of the new dojo. Those interested in learning more about Såzen Sensei can consult his group’s website: http://www.kakudokan.no/

Part Two: Naming A Dojo

Question: The dojo in St. Catharines has been given an official name. Can you tell us about it?

Sensei: Sure, I’ll try to explain it. The dojo name is “Jigan Dojo”.

The dojo name plaque.

JI: The most commonly used meaning is COMPASSION. In a dojo context, this refers to the deeper philosophical meaning of budo, which is not to kill but to preserve life. In other words, our true purpose in budo is not to harm others but to develop our skills. And since the Dojo is a place for developing character and manners, empathy is a paramount value.

GAN: The literal meaning is “EYE”. As practitioners we take a good look at ourselves, and our own conduct, and by introspection we learn who and what we are. But also, as budo-people, we must use observation as a means of learning. We learn by watching. Specifically in actual combat, our life may depend on right observation, meaning just looking at, and carefully observing our opponent. If you recall my talk about the concept of “look-move-respond”.*

*

Sozen sensei talked about this concept in last year’s interview

here.

DO: The noble path each individual has to walk by himself, and for himself and others equally.

JO: A specific or designated area or place used for practicing and realising one’s path.

Question: Why was it important for the dojo to have a name?

Sensei: Well, most dojos have a name. Even inside a Buddhist monastery, there are many rooms. Several “dojos”, places for study. And it’s not uncommon to have several names. It’s just like in a regular school. There are different classrooms, each with their own classroom number. Example, Room 201, Room 202, etc…

Question: Why are there different names?

Sensei: Because a monastery is basically a school. So for example, if the next lesson in school is chemistry, you would go to the Chemistry Room. Or if the next class is mathematics, you would go to the Mathematics Room. It’s for reference. All these rooms house various and different activities, so they are called “dojos”. And some people get to name them.

Question: So who would get to name a dojo?

Sensei: In modern days, building new monasteries is very rare. But in old times, teachers came by to teach. You see, various monasteries have connections to various teachers. Some are live-in teachers and some are visiting teachers. These are external teachers and they might be an abbot or a priest-scholar from another temple or monastery.

In our history, we have had teachers without a temple. In other words, they are not attached to any one temple. They travel around. It’s not usual but it’s not unheard of either. It’s like in the modern school system, there are some teachers that travel around.*

* examples would be

resource teachers,

teaching specialists, special education consultants, school

psychologists, speech and language pathologists, etc… These

types of teachers are not fixed to any one school location but are

employed by the Board of Education and go where needed.

Sometimes, these teachers would be asked to name a room or dojo. It would be an honour, and the name would last for centuries. And they knew this. So they’d bring out their best brush, best paper, best ink, and would write something really good. Then it’d be mounted and hung according to their traditions.

Question: So, in the case of Dennis Wiens’ dojo?

Sensei: The naming in this case, when Dennis wanted a name for his dojo and if you wanted it in the Japanese tradition, you would naturally consult someone with some knowledge about how to do it. We considered a lot of ideas. It was based a little bit on his personality, how he teaches, his hopes for a place like this, etc…

Question: So, how did you finally decide on those Kanji (Japanese characters) for the dojo name?

Sensei: Putting Japanese characters together is difficult. Finding characters that truly go well together in combination is tough. Like “Ji”. It means compassion and it also means consideration. Part of our training in martial arts is to consider others. For example, I am training with others so it is an important aspect, to think about my partners. And we decided on “Jigan” because we thought about how it is a kendo dojo* and also a Katori Shinto Ryu dojo. And of course, one of our starting positions is seigan (in kendo, chudan).

*

Dennis Wiens Sensei is also a 2nd

dan in kendo and one of the head instructors of the St.

Catharines Kendo Club.

Yoshio Sugino Sensei performing seigan no kamae (hidari hanmi)

And seigan is also a Buddhist term and the character “gan” in seigan is the same as the character “gan” in Jigan.

Question: Why is “gan” a good word?

Sensei: Let’s go back to “seigan”. You position yourself with a sword. Because kamae means position.*

*

Sozen sensei talked about the concept of kamae in last year’s

interview here.

And seigan is also an old Buddhist term. Sei means “pure”. Gan means “eye”. So seigan is literally “pure eye”. Pure eye has not so much to do with the physical eye but more to do with state of mind. This state of mind is called “pure eye”, meaning “no assumption”, “no preconceived ideas”. So this is a very Zen Buddhist kind of term. Remember, Doug, when old Sugino* started practice, he said… “seigan!”?

* Yoshio Sugino Sensei

(1904-1998)

Question: Yes, I remember. (Smiling and nodding).

small group photo from 1991-1992 (?) at Sugino Dojo in Kawasaki

(from left to right: D. Tong (the author), Yoshio Sugino sensei, Såzen Sensei, an unknown foreign student)

Sensei: He didn’t say “seigan no kamae”. He said “seigan!” It was no mistake. His meaning was “pure eye”, “observe”, “watch”, “don’t have preconceived ideas”. He was a devoted Buddhist, you know. Students might think “I’ve done this a thousand times!” All these kinds of preconceived ideas. None of those were acceptable.

“Just…now”.

“In this moment”.

That’s what he meant.

I earlier asked Dennis if he would like a Japanese name for his dojo and he said yes, so I promised that I would find one and offered to create one for him.

Question: So, you like this name?

Sensei: Oh, I think it’s a great name. You know, the eye is not a physical eye. We can observe others and we can observe ourselves. In Zen Buddhism, we have a saying:

“We have to turn our eyes and ears inward for introspection.”

Dogen Zenji

Zen Master, 1200-1253

So “eye” is a very good character.

“seigan”

(calligraphy written by Såzen Sensei)

Question: Do you have any final words for our readers?

Sensei: Well, for the fourth year, being invited back to teach and to be invited to do a blessing ceremony has been a wonderful thing. Thank you all. And I hope that this dojo will be a very beautiful dojo and that it will serve people well.

Question: Thank you once again for another great interview.

Sensei: Oh, you’re most welcome. Thank you everyone!

*

For more information about

Jigan Dojo, please see their website: http://www.jigandojo.com/

Author’s Post-Script:

Såzen Sensei brings up an interesting point about the monastery being basically a school in olden times. This was certainly the case in Europe, where the only learning in the post-Romanic era resided almost exclusively in the churches:

“According to the Oxford Dictionary, the term ‘dark ages’ was originally applied to the Middle Ages, to denote the intellectual darkness of the times… Public schools had long since ceased to be, and the study of letters was preserved only in monasteries and a few bishops’ households; the enlightened bishops were in most cases themselves monks… Elementary education, where it existed at all, was almost entirely personal – that of the gifted priest teaching his clerk* or a forward boy of his parish.

This simple framework was all that existed – and that only when wars, invasions and human inertia permitted – from 800 till well after A.D. 1000. Monks received what their elders in the monastery had to give; children, whether children sent by their parents to the priest, or oblates taught by their master in the cloister, learnt grammar and psalmody; the fortunate might receive instruction in letters and elementary calculation in the schools of a monastery or a cathedral city; theology was the only ‘advanced’ study, either in the monastery or in the bishop’s familia. There was no higher education north of the Alps, nor any professional class of teachers whether lay or clerical. Clearly, any philosophical activity was out of the question.”

Source: Knowles, David, 1962. The Evolution of Medieval Thought (pp.71-73). New York: Random House.

(The Dark Ages was a “… period of intellectual darkness between the extinguishing of the light of Rome, and the Renaissance or rebirth from the 14th century onwards.” See Dark Ages )

* this same relationship is played out in the famous book The Name of the Rose by Umberto Eco and the brilliant 1986 film by the same name The Name of the Rose starring Sean Connery as the visiting Franciscan friar William of Baskerville sent to investigate a series of mysterious deaths in an isolated abbey in Northern Italy. William is accompanied by his novice Adso of Melk. As a result of the events that transpire during their investigation, Adso learns a lot about life, about education, and about the way the world worked in his time. His final lines are stirring:

“I have never regretted my decision, for I learned from my master much that was wise and good and true. When at last we parted company, he presented me with his eyeglasses. I was still young - he said - but someday they would serve me well. And in fact, I'm wearing them now on my nose as I write these lines. Then he embraced me fondly - like a father - and sent me on my way. I never saw him again, and know not what became of him, but I pray always that God received his soul, and forgave the many little vanities to which he was driven by his intellectual pride. And yet, now that I am an old, old man, I must confess that of all the faces that appear to me out of the past, the one I see most clearly is that of the girl of whom I've never ceased to dream these many long years. She was the only earthly love in my life, yet… I never knew, nor ever learned, her name.”

This mirrors the traditional method of education in martial arts dojos, namely direct oral transmission from teacher to student, master to apprentice. Education is very important and dojos are important in this regard, as places of learning and intellectual (and spiritual) enlightenment. When we practice in a dojo, we need to keep this in mind. It is a place of learning and a place for the cultivation of the soul.

It is not difficult to remember this purpose in dojos for tea ceremony or other such refined arts but we seem to forget this in martial arts dojos. We are not there to beat each other up or show how powerful we are or to quench our desire for combat. We are there to learn, to be educated. Teachers likewise must keep this in mind. For those of us who are teachers, we are there to educate, not to stroke our own ego. We cannot stress enough the importance of “education” in the martial arts. Because without education (technical, yes, but more importantly moral and spiritual education), we are back in the Dark Ages.

Mr. Tong introduced Sugino-style Katori Shinto Ryu to Canada in 1994. His students and his students’ students have gone on to become official members of Sugino Dojo and some have been ranked by Sugino Yukihiro Sensei himself. He can be contacted via email at: doug@dragonfencing.com