Tamio "Tommy" Kono is the most successful Japanese American weightlifting competitor of the twentieth century, and among the best Olympic weightlifters of all time.

Kono was born in Sacramento, California, on June 27, 1930. The fourth (and youngest son) of Kanichi and Ichibi (Ohata) Kono, his eldest brothers were twins, John and Mike (8 years older), and his next brother was Frank (5 years older).

Kono's older brothers were all born in North Platte, Nebraska. Kono's father had saved his money and was planning on permanently relocating to Japan in 1930 but before the family left the Depression started and as a result it stayed in the US instead. It relocated to Sacramento, California, however, because there were more people of Japanese ancestry living there than in North Platte.

As a child Kono suffered from asthma and his parents tried a variety of traditional Japanese remedies including moxabustion and powders made from bear kidneys and snakes. "I used to wish with all my might for good health," he later recalled.

Toward taking his health into his own hands, during early 1942 Kono sent a penny postcard inquiring about the Charles Atlas bodybuilding course. He received a measurement form by return mail, and his brother Frank recorded that at age 11 young Tommy stood 4'8-1/2" tall, and had a 29" chest, a 26" waist, and a body weight of 74-1/2 pounds. But, as he didn't have the $36 the Atlas course required, he never enrolled.

About 120,000 Japanese Americans were forcibly evacuated from the Pacific Coast between March and July 1942, and in June the Kono family was sent to the Tule Lake Relocation Center in northern California. Life in the relocation center was unpleasant so as soon as they could his older brothers left for jobs back east. Kono and his parents, though, remained at Tule Lake until December 1945.

Being young, Kono was unaware of the great political division within the Tule Lake community. Meanwhile the desert air cured his asthma and he had lots of time to spend with his friends. Among these friends were Ben "Ace" Hara and Tad Fujioka, who in late 1944 or early 1945 gave him a fifteen-pound barbell and the advice, "It's good for you, keep lifting it up, lots of times." Kono's maximum effort on his first try was 55 pounds three times and 65 pounds once.

The barbell Kono started with was owned by Block 27, whose young people had raised the money they needed to buy sports equipment, including a York "Ten-in-One" exercise kit, by running a carnival hamburger stand. Their gym was separate from the better-known one established in 1944 by the Olympic weightlifter Emerick Ishikawa.

Although Kono didn't then know Ishikawa

personally, he did see him put on a demonstration that included some posing

and handstands. He also saw the Olympic weights Ishikawa lifted. "They

looked like train wheels to me!" Kono later recalled.

Kono's early weight program consisted

of lifting light weights three or four times a week for maybe an hour per

session. His goal was not bodybuilding but simply increasing his overall

strength and flexibility. To this day he believes that everyone should

start slow and work their way up. A training program, said Kono in 1990,

should include both long-range and short-range goals. "But be realistic

about your goals," he added, "and give yourself ample time to reach these

targets."

Following release from Tule Lake, Kono returned to Sacramento with his parents. After graduating from Sacramento High School he worked for the California Motor Vehicle Department and attended Sacramento Junior College. Meanwhile he played basketball in a Buddhist church league and lifted weights at the Sacramento YMCA.

In March 1948 Kono decided to accompany his friend Mits Oshima to the Northern California AAU weightlifting championships. Since he would be there anyway, he also decided to enter the competition. There were only two entries in Kono's division and he placed second. While hardly a spectacular debut, Kono enjoyed the experience and continued entering local competitions. His rapid improvement impressed the onlookers. For example, Chet Teegarden, commissioner of AAU weightlifting in Sacramento, later recalled seeing Kono during a contest held in Sacramento in December 1948. "He didn't have much style but he pressed 190 pounds," Teegarden said in an interview published in Pacific Citizen in August 1952. "Later he did knee bends with 300 pounds. That same day he went up to 360 and did a half knee bend. That's something for an inexperienced 150-pounder."

Kono also began training at Ed Yarrick's gym in Oakland. This was one of the best weightlifting gyms on the Pacific Coast, and training partners there included Dan Uhalde, Art Jones, and Roy Hilligen.

In February 1949 Kono took first in the welterweight (148-pound) division and a year after that he broke four California lifting records. The latter feat brought Kono to the attention of Sacramento sportswriter Wilbur Adams. His goal, Kono told Adams in a published interview, was to make the 1952 Olympics. As for weightlifting itself, Kono told Pacific Citizen in March 1950, "Anyone can learn the sport. It may not sound like a great deal of fun to an outsider, but it is like mental development. You get your pleasure out of the results. As you grow stronger, you work harder at it."

This was not idle talk, either, as during the Pacific Coast AAU weightlifting championships held in Berkeley, California on April 29, 1950 Kono took first with a total lift of 780 pounds. Two weeks later Kono placed second in the US Nationals in Philadelphia with a total lift of 760 pounds.

In September 1950 Kono flew to New York to participate in the World Championship tryouts. He didn't want to go because he was working nights and caring for his sick mother during the day. Plus, "at the time, plane fare was very expensive," Kono recalled. "Only rich businessmen flew, not normal people." Then Bob Hoffman, the US Olympic team's coach, wrote letters to the Sacramento newspapers asking that the Californians pitch in to send Kono to the Nationals. As Hoffman put it, he was spending his own money organizing a US team, so it was the least that Sacramento could do to spend its money to send a local lifter to the nationals. So the money was raised, explained the Pacific Citizen in February 1951, "when members of the Oak Park Athletic Club, a group of high school athletes in Sacramento, raised more than $300, partly from a bank loan. The Oak Park club staged a dance and sold cakes to obtain the money for Kono's trip."

"It was embarrassing to receive funds from others," Kono told Brian Niiya in May 1999, "not like today." But with so many people involved, he felt obligated to go to New York, and do well. The timing was poor, however, as the day before the competition he received a telegram saying that his mother had died. As a result Kono was not at his best and despite having lifted more than the current champion during training, he lifted less in the finals and ended up taking second. Disappointed, "I didn't even feel like coming home," he told Niiya, adding that the train ride back to Sacramento was a terrible time.

Soon after returning home he received his draft notice. During basic training at Fort Ord, California he was given the choice of becoming a cook, a clerk-typist, or a medic, and he chose cook. "All I knew," he said in an interview published in Iron Masterin 1990, "was that as a cook you could work one day and get the next day off. I did it so that I could train on my day off."

Unfortunately the Korean War was then on and North Korean infiltrators were notorious for shooting cooks. Therefore his days off were spent at the rifle range learning to shoot rather than at the gym lifting weights. His name was on the list to be sent to Korea, too, when his commander realized he had an Olympic potential on his hands. As a result Kono was taken off the overseas rotation list and instead made an instructor at the base gym at Fort Mason, near San Francisco.

With his time to lift assured, Kono was thus able to continue his Pacific Coast dominance. For example, in December 1951 he won the 148-pound division during a Pacific Coast competition held in Oakland and in January 1952 he set an unofficial US record during a YMCA tournament held in San Jose. During this period his training consisted of working out for 75 minutes three times a week. He also discovered the value of great leg strength. To develop it, he forced himself to do lots of heavy squats, a decision that later reaped great reward.

On May 3-4, 1952 Kono attended the Junior Nationals in Oakland, California, where he set three US and one world's record. This pleased the Army, which subsequently paid for Kono's trip to New York to try out for the Olympics. In the meet held at St. Nicholas Arena on June 27-28, 1952, Kono was the individual star and as a result was picked for the Olympic team.

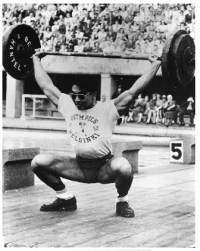

The Olympics were held in Helsinki, Finland and the weightlifting events took place July 25-27, 1952. Despite an attack of food poisoning the night before, on July 26, 1952 Kono won a gold medal and set a world record in the snatch.

[Tommy Kono at the Helsinki Olympics, 1952. Photo gift of the Kono Family (97.141.5), Japanese American National Museum]

There was a controversy at these Olympics when two US champions were left off the team that entered the finals. The press made a big deal out of it, and Kono felt sorry for the men involved. Nevertheless, he as he told Brian Niiya, "They knew the score. You had to go with the guys who had the best chance of scoring points." And during the 1950s the score was doing whatever it took to beat the Russians.

In Helsinki many people remarked the fact that Kono wore eyeglasses and street shoes while lifting. "They're street shoes, it's true," said Chet Teegarden in the Pacific Citizen in August 1952. "But something has been added. Tommy had another narrow layer of leather placed in the heels of his shoes. He uses the squat style, resting on his heels, so the extra piece of leather raises his heels, moves the center of gravity forward and improves his performance."

Following the Olympics Kono, along with the other members of the US Army weightlifting team, was transferred to Germany. The idea was to allow the soldiers to easily travel to European meets. And travel he did. For example, on January 10, 1953 he and Clyde Emrich were in London, where during competition they beat two Australian weightlifters despite giving them a 200-pound handicap advantage.

Following his discharge from the Army in March 1953 Kono continued lifting three to four times a week, averaging between an hour and an hour and a half a session. To combat boredom, he changed his routines every three weeks.

This system worked well, too, as on June 6-7, 1953 he set an unofficial world's record in the press during a meet in Indianapolis. Two months later in Stockholm he took first in the 165-pound division and set a clean-and-jerk record. And in between he won a Mr. World physique title.

Such a busy schedule was typical, as in 1954 Kono set nine US and four world's records. What drove him was having seen what happened to the fine African American lifter John Davis, who had easily won several titles and then not had the edge he needed to overcome a serious challenge faced in 1953. "Breaking records was one way not to get stagnant," Kono later explained.

In March 1955 Kono was in Mexico City for the first Pan-American weightlifting championships. To take first he pressed 316.25 pounds, another world record. On June 4-5 he was in Cleveland, Ohio for the US Nationals. To no one's surprise, he took first at 181 pounds with a combined lift of 940 pounds. After that the American team of which Kono was part visited the USSR, Egypt, and Iran. And, to keep from getting bored, he also found time to be crowned Mr. Universe.

After returning to the United States Kono decided to move to Hawaii. He had first visited Honolulu in November 1953 and after the Pan-Am Games of 1955 moved there upon being offered a job selling dietary supplements. His partners in the latter business included Dr. Richard You, who was a pioneer of athletic nutritional programs, and the former Olympic weightlifter Emerick Ishikawa.

Although Dr. You paid Kono a small salary

and let him live in his house, Kono's training and competition schedule

prevented any serious non-competitive career ambitions. "Weightlifting

has to come first -- ahead of everything," Kono told Steve Lum in 1985.

His schedule remained hectic. For example,

in October 1955 he competed in the World Championships in Munich, then

went on a State Department trip through Asia, with stops in Iran, Iraq,

Afghanistan, India, and Burma. Upon returning to Hawaii in late December

1955 he started attending (and winning) a tournament a month. But the effort

was worthwhile because in the 1956 Olympics he won a gold medal and set

a world record in the clean and jerk.

With two Olympic gold medals Kono thought about quitting competitive lifting, but Dr. You talked him out of this. The following year Kono also severely injured his left hand when a car door closed on it. But with the use of straps he was able to continue lifting and on June 22, 1957 he took first place in the US Senior Nationals. That November he also took first place in the World Championships in Tehran (the only US lifter to do so) plus won Mr. Universe.

This was the height of the Cold War, and Bob Hoffman, coach of the US Olympic weightlifting team, was obsessed by the desire to beat the Soviet team whenever possible. Toward that end, Kono competed at whichever of three different weights offered the US the greatest opportunity of defeating the Soviets. The way Kono added weight was by eating six or seven meals a day. To lose weight, he simply cut back to three.

In June 1958 Kono attended the US Nationals in Los Angeles. To take first place in the 165-pound division he lifted ten pounds more than did Jim George, the winner at 181 pounds. The following month Kono was in York, Pennsylvania to participate in the US Nationals. Although no world records were set, Kono was chosen best lifter. At 165 pounds, his winning lift was still five pounds heavier than that of the 181-pound champion Jim George. A month later Kono was at the Pan-Am Games in Chicago. This time he won the 165-pound division with a lift that was twelve pounds heavier than George's first place win at 181 pounds. And in September 1958 he went to Stockholm to participate in the World Championships, where he won his seventh consecutive championship at 165 pounds, setting two new records in the process.

In October 1958 Kono won his eighth consecutive world title, a record that represented the high water mark of his competitive career. Although he easily won a place on the US Olympic team in June 1960, in Rome he was defeated for the first time in eight years and ended up taking silver instead of gold.

Disappointed, he gave thought to retiring but then decided to redouble his efforts instead. At first this worked; in Moscow in 1961, he set world records in the press and the total. But later that year he failed to make 165 pounds during the World Championships held in Vienna -- his scales and the official scales were at variance -- and as a result was forced to compete at 181 pounds, where he placed a disappointing third.

Kono went to Moscow in March 1962, but failed to place after missing all of his snatch attempts. At the US Nationals later that year he won, but was pushed by Lewis Rieke. Kono also had problems in Budapest during the World Championships, where he finished second. Admittedly that was the highest finish of any US athlete, but it still was not first.

Kono finished his international competitive career in 1963. In March he placed third in a contest in Moscow. In April he took first at the Pan-Am Games in Brazil, a feat he repeated at the US Nationals in June. But, in his last competition ever, the World Championships in Stockholm, he missed all of his snatches -- he had previously smashed his thumb between two plates and was unable to train properly -- and so was disqualified.

Nineteen sixty-three was also the last year that Kono was selected to compete for the AAU's James E. Sullivan award. Awarded to the outstanding US amateur athlete of the year, it was Kono's seventh consecutive selection, and for the fourth straight year he placed second in the polling. John Davis is the only other weightlifter to have been a finalist.

During the Fourteenth National YMCA Championships held in Los Angeles in April 1964, Kono won the 165-pound division. Although his totals set three National YMCA records, they were still 170 pounds behind his personal best. As a result he did not attend the Olympic tryouts, and so was not selected for the 1964 Olympic team. His last competition was therefore his third place finish in the US Senior Nationals held in Los Angeles on June 12, 1965.

Realizing he would soon need a new career, in 1964 Kono opened a gym at Wailuku, Maui. (He didn't want to open a gym in Honolulu because his friends already had gyms there, and he didn't want to cut into their business.) But Maui didn't have many serious lifters so in 1965 he accepted a job coaching the Mexican national weightlifting team. After that the West Germans hired him to coach their Olympic weightlifting team, a job he held until 1972. The Canadians then offered him a job coaching their national team, but he turned that down. "After living in West Germany for four years I wanted to return to the US," Kono told Steve Lum in November 1985. "My son didn't even know what baseball was." So he and his family returned to Oahu, where he got a job with the City of Honolulu. He remained active in US Olympic weightlifting, however, and was also the head coach of the US men's team from 1972 to 1976 and the US women's team from 1987-1990.

The key to his success, Kono said, was his mental training. "Successful weight lifting is not in the body," Kono told a reporter from Time in June 1960. "It's in the mind. You have to strengthen your mind to shut out everything -- the man with the camera, the laugh or cough in the audience. You can lift as much as you believe you can. Your body can do what you will it to do."

Toward building his mind, Kono said, "I just stress the positive aspects of life -- it's always worked for me." As for training, much of it was done alone in his basement. Kono always thought that this helped him overcome his personal limitations by teaching him to concentrate.

Regarding opponents, Kono said, "I don't think of my opponent, even in a close contest. I never would say to myself, 'I hope he slips.' That's a negative attitude. Saying that, you're relying on outside help to win. Prayer doesn't help, either. That's also relying on outside help. The will has got to come from me. It's all up to me."

And focus he could: "When Kono looks at

me from the wings," the Soviet lifter Fyodor Bogdanov once said, "it works

on me like a python on a rabbit." But while at the beginning the challenge

of lifting the bar was fun, in the end it became an ordeal. So, before

every lift in competition, he would say to himself: "Do I want to do this?"

The answer, journalist Grove Day observed

in 1960, was a resounding yes!

For a recent news article on Tommy Kono see: http://starbulletin.com/2000/09/30/news/story3.html

Acknowledgments

The assistance of Brian Niiya, Graham Noble, and Tommy Kono in preparing this article is gratefully acknowledged, as is the financial support of the Japanese American National Museum and King County Landmarks and Heritage Commission.

For further reading, see:

"Atlas Come to Life," Time, 75, June 27, 1960, 69-70.

Day, A. Grove. "America's Mightest Little Man," Coronet, 48:3 (July 1960), 108.

"The Incredible Tommy Kono," Iron Master, reprint August 1993, no. 5, December 1990.

Lum, Steve. Hawaii Herald, November 15, 1985, 7.

Reynolds, William Mason. "A History of Men's Competitive Weightlifting in the United States from its Inception through 1972," unpublished MS thesis, University of Washington, 1973.

Wallechinsky, David. The Complete Book

of the Summer Olympics (Boston: Little, Brown, 1996), 738.