Bekris E.¹, Gissis I.², Sambanis M.², Milonys E.¹, Sarakinos A.¹, Anagnostakos K.³

Department of Physical Education and Sport Science,

National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece

2. Department of Physical Education and Sports Science Serres,

Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece

3. General Hospital of Athens “KAT”, A΄ Orthopaedic Department, Greece

Abstract

The aim of the present study was to investigate the physiological and technical-tactical effects of an additional soccer player’s participation in small sided games 1Vs1 & 2Vs2. Three cases were examined: when the additional player was a) a neutral player with a constantly attacking role (NA), b) a neutral player with a constantly defensive role (ND), and c) participated in a team giving it a constant supernumerary against the opposing team. Sessions 1Vs1, 1Vs1+1ΝΑ, 1Vs1+1ΝD & 2Vs1 comprised Category 1 (C¹), while sessions 2Vs2, 2Vs2+1ΝΑ, 2Vs2+1ΝD, & 3Vs2 comprised Category 2 (C²). Eight amateur male soccer players (age 17.4±0.6 years, height 1.73±0.05 m, body mass 64.0±6.8 kg, training age 8±1.4 years) participated in the study. Heart rate, blood lactate concentration and technical-tactical skills were recorded in each session. We used οne way anova with repeated measures for the physiological analysis and McNemar's test for the technical-tactical skills. Statistically significant discrepancies were checked at a significance level of a = 0.1.

The results showed that in C¹ & C² sessions, there are significant differences in players’ technical-tactical skills, attributable to the specialized and varied attacking and defensive situations generated by the additional player’s participation. High average HR (90 – 95% HRmax) as well as high Duration with intensity > 85% HRmax mark them out as being ideal for the improvement of aerobic and anaerobic capacity. Practice characteristics must be adapted to the players’ level so execution quality is unaffected. C¹& C² games’ usefulness is instrumental in soccer teaching.

Key words: Small sided game, soccer, additional, neutral player.

Address for correspondence

Dr. Bekris Evaggelos

Department of Physical Education and Sports Science of Athens University

41 Ethnikis Antistaseos Str., 172 37 Daphne – Athens, Greece

e-mail: vag_bekris@yahoo.gr

INTRODUCTION

In high performance sports, it has been well accepted that the maximum benefits of exercises are achieved when the training stimuli are similar to the competitive demands generated by the match itself (Mallo, & Navarro, 2008). Small sided games (SSG) constitute a popular and specialized training category for adult and young soccer players which takes place in a smaller field with fewer players (Rampinini et al., 2007). Small sided games training improves the players’ technical and tactical skills, increases their fitness through real game conditions and saves time during practice (Helgerud, Engen, Wisløff, & Hoff, 2001; Rampinini et al., 2007; Hill-Haas, Dawson, Coutts, & Rowsell, 2008; Impellizzeri et al., 2006; Little, & Williams, 2006). The smaller field and number of players allow more frequent contact with the ball and bigger participation in basic and essential technical-tactical actions in real match conditions (Capranica, Tessitore, Guidetti, & Figura, 2001). Small sided games practice can be modified and implemented according to the goals set by the coach each time. Previous studies have examined the factors which affect goal attainment in competitive games and suggest that the physiological and technical-tactical demands during such games can be modified according to field dimensions, the number of the participating players, the changing or not of the rules, the use of the goals, and, naturally, the trainers’ urging (Grant, Williams, Dodd, & Johnson, 1999a; Grant, Williams, & Johnson, 1999b; Little, & Williams, 2006; Little, & Williams, 2007; Owen, Twist, & Ford, 2004; Platt, Maxwell, Horn, Williams, & Reilly, 2001; Williams, & Owen, 2007). All those studies, however, used teams with equal numbers of players. Nevertheless, it is known that during the game, there are conditions in which the number of players is not equal. Such phases generate different attack and defense tactics. Therefore, to better deal with such conditions, more specialized training in competitive games is imperative. The aim of the present study is to investigate the physiological and technical-tactical effects of an additional footballer’s participation in small sided games. More specifically, we will examine how the technical-tactical characteristics change according to the additional player’s role, namely, when he:

a) is a neutral player with a constantly attacking role (he collaborates with the team that possesses the ball).

b) is a neutral player with a constantly defensive role (he collaborates with the team that does not possess the ball).

c) generates permanent inequality in the number of the opposing teams’ players.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Participants

Eight male soccer players (age 17.4±0.6 years, height 1.73±0.05 m, body mass 64.0±6.8 kg, and training age 8±1.4 years) participated in the study. All players were members of the same amateur team, and practiced 3 times / week. All players and parents were notified of the research procedures, requirements, benefits, and risks before giving informed consent. A university Research Ethics Committee granted approval for the study.

Research planning

The players participated in two categories of competitive games: C¹ & C². Each category included 4 different sessions, played on the same day, while between the practices of two different competitive sessions, there was a 72-hour recovery. Each small sided session lasted 3 min and the recovery lasted 12 min (proportion: exercise/recovery 1/4). The recovery was active with the players passing the ball or keeping it in the air in pairs. The average small sided games dimensions were used (Owen et al., 2004). Those dimensions were kept constant in all facets of each small sided game (table 1), since analyzing how much intensity is affected by the number of players, the field dimensions must be constant (Rampinini et al., 2007).

In the first exercise, the teams had equal numbers of players. In the second one, the extra player participated as a neutral player who helped the team that possessed the ball (neutral –attacker NA) and he played with one contact with the ball. In the third one, the extra player participated as a neutral player who helped the team that did not possess the ball (neutral – defender ND) and he played with one contact with the ball on intercepting it from the opposing team. In the fourth exercise, the player was a member of the same team, thus generating a permanent supernumerary in favor of that team.

Table 1. Forms of competitive games dealt with in the research and their characteristics.

|

Games’ Categories |

Small sided games |

Dimensions |

Duration of exercise |

Recovery |

|

Category 1 (C¹) |

1Vs1, 1Vs1+1ΝΑ, 1Vs1+1ΝD, 2Vs1 |

10 x 15m |

3 minutes |

12 minutes |

|

Category 2 (C²) |

2Vs2, 2Vs2+1ΝΑ, 2Vs2+1ΝD, 3Vs2 |

15 x 20 m |

3 minutes |

12 minutes |

Procedure

Prior to each session, there was a specific 20-minute warm-up. The games were played under the researches’ guidance, aiming at ball possession, and there were no goalposts. The players played freely without any restrictions, except for the neutral player, who was restricted to one contact with the ball. There was constant encouragement on the researchers’ part with expressions like ‘push’, ‘play fast’, ‘move’. Many extra balls were around the perimeter and were thrown into the field by the researchers whenever the ball was out to maintain vigorous exercise. All the testing sessions took place at the same time of day to remove the effects of circadian variation (Reilly, & Brooks, 1986). All games were carried out on artificial grass.

Measurements

Heart rate monitoring

Heart rate was recorded at 4-s intervals during each small-sided game via short-range radio telemetry (Hosand TM Group System).

Maximum heart rate measurement

Each player’s maximum heart rate was measured as he performed the 20 m Multi-Stage Fitness Test (20 m MSFT).

Lactate measurement

Blood lactate levels measurement was performed 3 minutes after each game ended Dellal, Hill-Haas, Lago-Penas, Chamari (2011) by means of a portable blood analyzer (Lactate Plus – Nova Biomedica).

Technical-tactical skills measurement

Each game was filmed using a camcorder (Canon Legria FS200) to evaluate the technical actions taking place during each game condition. For each game’s technical analysis, ten technical-tactical variables were used, based on Owen et al. (2004) (Table 2). The technical-tactical skills were recorded per player and team in a special notebook in every game.

Table 2. Technical-tactical skills measured in SSG.

|

Skill |

Description |

|

Pass |

Player in possession sends the ball to a team mate (eg using the foot, thigh or chest; using various techniques such as ground, lofted, chip, flick or volley; over short or long distances). |

|

Receive |

Player gains or attempts to gain control of the ball in order to retain possession |

|

Turn |

Player in possession, with ball at feet, changes direction in order to play in other areas of the pitch. |

|

Dribble |

Player in possession, with ball at feet, runs with ball, beats or attempts to beat an opponent. |

|

Header |

Player contacts the ball using their head. |

|

Tackle |

An action intending to dispossess an opponent who is in possession of the ball |

|

Block |

Ball strikes a player, preventing an opponent’s pass from reaching its intended destination. |

|

Interception |

Player contacts the ball enabling him to retain possession, preventing an opponent’s pass from reaching its intended destination. |

|

Change of ball possession |

Rival teams possess ball alternately |

|

Wall pass |

Player passes ball to fellow player who, in turn, passes it back to him on his course. |

Statistical Analysis

The Physiological Analysis is based on the repeated measures ANOVA which is the equivalent of the one-way ANOVA but for related not independent groups and is the extension of the dependent t-test. A Repeated Measures ANOVA is also referred to as a within-subject ANOVA or ANOVA for correlated samples. All these names imply the nature of the Repeated Measures ANOVA that of a test to detect any overall differences between related means. There are many complex designs that can make use of repeated measures but, throughout this guide, we will be referring to the most simple case, that of a one-way Repeated Measures ANOVA. This particular test requires one independent variable and one dependent variable. The dependent variable needs to be continuous (interval or ratio) and the independent variable categorical (either nominal or ordinal).

We used McNemar's test for the technical actions which is a non-parametric method used on nominal data. McNemar's test assess the significance of the difference between two correlated proportions, such as might be found in the case where the two proportions are based on the same sample of subjects or on matched-pair samples. Statistically significant discrepancies were checked at a significance level of a=0.1

RESULTS

Category 1

Table 3. Means and SE in C¹ Technical-tactical skills.

|

Technical-tactical skills |

1vs1 |

1vs1 + 1 NA |

1vs1 + 1 ND |

2vs1 |

|

Turn |

9.5±0.70 |

5.0±2.82 |

16.0±5.65 |

14.0±1.41 |

|

Dribble |

2.0±0.00 |

1.5±0.70 |

3.0±1.41 |

2.5±0.70 |

|

Tackle |

1.5±0.70 |

2.5±0.70 |

0.0±0.00 |

3.0±1.41 |

|

Interception |

6.5±2.12 |

5.5±2.12 |

3.0±1.41 |

4.5±2.12 |

|

Receive |

0.0±0.00 |

14.0±0.00 |

10.5±3.53 |

10.5±14.84 |

|

Pass |

0.0±0.00 |

15.5±4.94 |

3.0±0.52 |

10.0±14.14 |

|

Header |

0.0±0.00 |

0.0±0.00 |

0.0±0.00 |

0.0±0.00 |

|

Block |

0.0±0.00 |

6.5±2.12 |

0.0±0.00 |

4.5±6.36 |

|

Change possesion |

6.5±2.12 |

5.0±1.41 |

8.0±1.41 |

2.0±1.02 |

|

Wall pass |

0.0±0.00 |

6.0±1.41 |

0.0±0.00 |

1.0±1.41 |

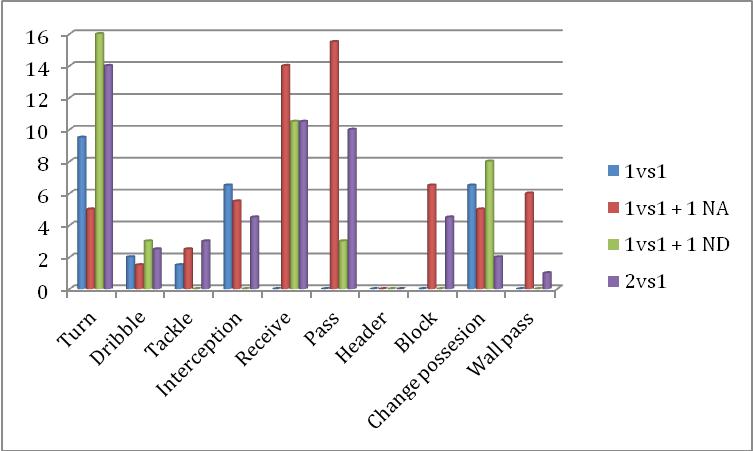

Figure 1. C¹ Technical-tactical skills bar.

|

Physiological parameters |

1Vs1 |

1Vs1 +1 NA |

1Vs1+1ND |

2Vs1 |

|

Mean HR (b/min) |

184 ±5.65 |

177.3±8.62 |

178.7±7.57 |

174.7±8.38 |

|

Mean HR (%HRmax) |

0.9±0.03 |

0.9±0.06 |

0.9±0.04 |

0.8±0.06 |

|

Mean Peak HR (b/min) |

192±5.65 |

187.0±7.54 |

191.3±2.88 |

181.0±15.13 |

|

Duration (% of total time ) with intensity > 85% HR max |

0.9±0.01 |

0.9±0.03 |

0.9±0.04 |

0.7±0.29 |

|

Lactate concentration (mmol/l) |

12.4±1.76 |

8.3±3.60 |

10.2±2.70 |

7.3±2.90 |

Category 2

Table 5. Means and SE in C² technical-tactical actions.

|

Technical-tactical actions |

2Vs2 |

2Vs2 +1 NA |

2Vs2 +1 ND |

3Vs2 |

|

Turn |

12.0±2.82 |

11.5±0.70 |

11.5±2.12 |

9.0±4.24 |

|

Dribble |

3.5±2.12 |

1.0±1.41 |

5.0±0.00 |

4.0±2.82 |

|

Tackle |

0.5±0.70 |

0.0±0.00 |

0.0±0.00 |

1.0±0.70 |

|

Interception |

9.5±0.70 |

5.0±0.00 |

3.5±0.70 |

4.0±2.82 |

|

Receive |

19.5±0.70 |

19.5±3.53 |

9.0±4.24 |

20.0±19.79 |

|

Pass |

12.0±1.41 |

20.5±14.84 |

7.0±1.41 |

28.5±37.47 |

|

Header |

0.0±0.00 |

0.0±0.00 |

0.0±0.00 |

0.0±0.00 |

|

Block |

6.0±0.00 |

4.0±2.82 |

4.0±2.82 |

5.0±0.00 |

|

Change possession |

10.5±0.70 |

6.0±2.82 |

4.5±2.12 |

5.5±0.70 |

|

Wall pass |

0.5±0.70 |

2.5±0.70 |

0.5±0.70 |

1.5±2.12 |

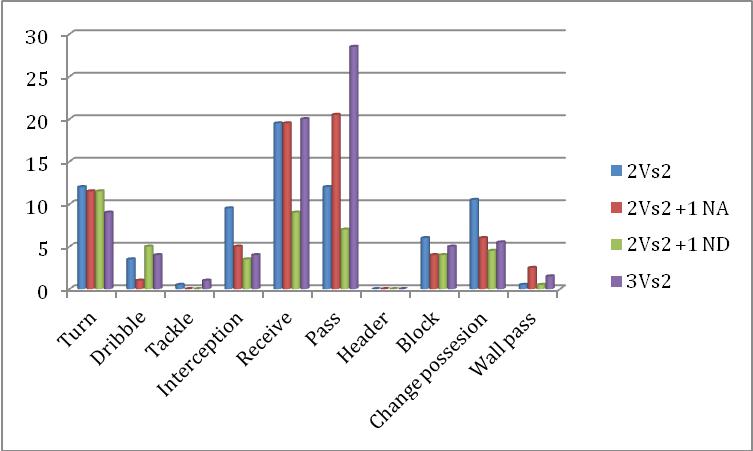

Figure 2. C² Technical-tactical skills bar.

Table 6. Means and SE in C² physiological parameters.

|

Physiological parameters |

2Vs2 |

2Vs2 +1 ΝΑ |

2Vs2 +1 ND |

3Vs2 |

|

Mean HR (b/min) |

180.7±3.36 |

180.7±3.36 |

176.3±6.46 |

177.0±5.43 |

|

Mean HR (%HRmax) |

0.95±0.01 |

0.95±0.01 |

0.9±0.02 |

0.85±0.01 |

|

Mean Peak HR(b/min) |

191.0±4.11 |

191.0±4.11 |

186.0±5.61 |

185.8±5.11 |

|

Duration (% of total time) with intensity > 85% HR max |

0.95±0.03 |

0.95±0.03 |

0.85±0.07 |

0.9±0.06 |

|

Lactate concentration (mmol/l) |

9.4±3.35 |

9.4±3.35 |

9.0±1.65 |

6.9±2.04 |

DISCUSSION

Technical analysis

Category 1(C¹)

Turns

There is a significant increase in the number of turns in 1Vs1+1ND as compared to 1Vs1 (p=0.061), which is attributable to the constant pressure by two players against the one possessing the ball. This way, more frequent and difficult implementation of turns is achieved, since the space one can move possessing the ball is reduced and the player possessing the ball must cope with a greater level of difficulty.

In the 2Vs1session, there was a significant increase as compared to the 1Vs1 + NA session (p=0.008). This is attributable to the obstruction in passing by the defender, who also strove to retain the ball. It is therefore evident that the players’ technical-tactical level and a change in the regulations of the game significantly alter the frequency of turns.

Moreover, there was a statistically significant difference between 1Vs1 + NA and 1Vs1 + ND (p=0.000). It is obvious that when the neutral player assumes a defensive role, there are many more turns, while when he assumes an attacking role with only one contact with the ball, the form of the game changes.

Reception with the ball

The addition of one extra player, regardless of his role (1Vs1 +1 NA, 1Vs1 +1 ND, 2Vs1) led to an increase in ball reception as compared to 1Vs1 (p=0.000, p=0.008, p=0.000), but in a different way and to a different extent. The NA addition and his restriction to only one ball contact generated many reception phases due exclusively to the two other players’ attacks against NA. ND presence led to two players’ attacking collaboration immediately after ND’s initial turn. In 2Vs1, receptions constantly took place between two players of the supernumerary team. It is therefore understandable that the additional player’s role changes the (statistical) distribution of receptions among the participating players.

Passing

There were significant differences between the following games: 1Vs1 ~ 1Vs1 +1 NA (p=0.000), 1Vs1 ~ 2Vs1 (p=0.000), 1Vs1 +NA~ 1Vs1 +1 ND (p=0.000), 1Vs1 +1 ND ~2Vs1 (p=0.000). It is evident that games 1Vs1 +1 NA and 2Vs1 boost attacking collaboration between two players, ergo there are more passes. The additional player’s role change generated different conditions and affected the number of passes in the respective sessions.

Block

There was a statistically significant increase in this variable in the 1Vs1 +1 NA session as compared to the 1Vs1 (p=0.063) and the 1Vs1 +1 ND (p=0.008) ones. NA presence enables the defender to practice ‘blocks.’ The statistically significant difference found in the 1Vs1 +NA session as compared to the 2Vs1 (p=0.008) one can probably be ascribed to one team’s constant numerical supremacy and the strain on the 2Vs1 defender, which change the form of the game. Thus, fatigue, which affects one team more, seems to differentiate the results.

Change of ball possession

There was a statistically significant difference between the 1Vs1 session as compared to the 2Vs1 one (p=0.063), and the 1Vs1 +1 ND session as compared to the 2Vs1 one (p=0.004). The results show that numerical supremacy (supernumerary) in 2Vsl along with the defender’s difficulty to gain ball possession or repossession led to a low frequency in change of ball possession. It is obvious that the transition from attacking to defending mode is not adequately improved in the 2Vsl session. Probably, these results change when the players’ technical-tactical and physiological levels change too.

Wall pass (1-2)

As far as wall pass (1–2) is concerned, there was a statistically significant difference between the 1Vsl and 1Vs1 teams (p=0.016), but not between the 1Vs1 and 2Vs1 ones. This is evidently due to the additional player’s restriction to only one ball contact, which forced the players to apply this very technical-tactical skill. It is therefore vital for the coach to choose the suitable exercise according to the goal he wants to achieve in order to deliver the best possible results.

Category 2 (C²)

Dribbling

Defensive supernumerary throughout 2Vs2 + 1ND, with ND’s constant defensive presence, led to statistically increased values as compared to 2Vs2 + 1NA in dribbling skills. There are also statistically increased values as compared to 2Vs2 and 3Vs2, albeit not statistically significant. This finding shows that constant defensive supernumerary forces the offenders to dribble in order to cope with the increased pressure from their opponents. Thus, it is self-evident that the 2Vs2+1ND game is the most suitable one to practice dribbling skills within the C² category.

Interception

According to the results, there are significantly more interceptions in the 2Vs2 session than in the 2Vs2+1ND session (p=0.092). Thus, it seems that the constant defensive supernumerary generated by the neutral defender is not a decisive factor in interception increase. This may be attributable not only to bad personal defensive tactic and inadequate defensive collaboration, but also to better attacking performance. Obviously, the neutral player’s and the teams’ tactical and technical levels differentiate the flow of the game, and therefore, the quantity and quality of the implemented skills. Also, there are more interceptions in the 2Vs2 session than in the 3Vs2 one (p=0.039). It is obvious that whenever teams have equal numbers of players, there are more interception opportunities.

Receptions

According to the results, receptions are statistically more in the 2Vs2 session than in the 2Vs2+1ND one (p=0.009), and in the 2Vs2+1NA session than in the2Vs2+1ND one (p=0.004). It seems that the game with a neutral defense player is not suitable for reception practice, since passing attempts are reduced because of the increased pressure.

Passing

The number of passes is higher when a neutral attacker is used (2Vs2 +1 NA) as compared to 2Vs2 +1 ND (p=0.000) where there is defensive supernumerary, so passing is more difficult. Also, in the 3Vs2 session there are more passes than in the 2Vs2 +1 NA (p=0.000) and the 2Vs2 (p=0.022) ones. Most probably, the permanent supernumerary conditions, both in attack and defense, and the free contacts with the ball generate more opportunities for ball possession and turns in the supernumerary team. Thus, there is more strain on the opposing team, and it is likely that this affects the number and the distribution of passes between the teams.

Previous studies compared technical-tactical data from sessions in which both teams had equal numbers of players (Jones, & Drust, 2007; Katis, & Kelis, 2009; Casamichana, & Castellano, 2010; Rudolf, & Václav, 2009; Owen, Twist, & Ford, 2004; Platt, Maxwell, Horn, Williams, & Reilly, 2001) and concluded that small sided games (SSG) help in the teaching and the tactic development of young soccer players (Hill-Haas et al., 2008; Rampinini et al., 2007). However, in none of these surveys were there different numbers of players in the opposing teams. As shown by this study, in each category (C¹, C²), sessions with an additional player generate different defense and attack demands, change the form of the game and the frequency of the skills. The results are varied, depending on whether there is constant or alternate supernumerary, and on the regulations under which the additional player participates. The conditions in those sessions resemble attack and defense conditions in real games where the number of the teams’ players is not equal. Thus, the usefulness of these sessions is huge for a more complete teaching of soccer.

Physiological Analysis

The determination of % HRmax in soccer drills is a popular approach to monitor the intensity of small sided games (Dellal, Jannault, Lopez-Segovia, & Pialoux, 2011; Hill-Haas, Dawson, Impellizzeri, & Coutts, 2011; Little, & Williams 2006; Dellal, Hill-Haas, Lago-Penas, & Chamari, 2011). Many studies examine the SGG intensity by measuring the heart rate (Coutts, Rampinini, Marcora, Castagna, & Impellizzeri, 2009; Dellal et al., 2008; Kelly, & Drust, 2009) and lactate in the blood (Hill-Haas, Coutts, Rowsell, & Dawson, 2008; Rampinini et al., 2007; Coutts et al., 2009). Nevertheless, no study has ever examined the physiological effects of SSG with the participation of one additional player.

Category 1(C¹)

According to the results, in this category, the intensity of the sessions is high (approaching 90% HRmax) without any statistically significant difference among the games. The only exception is the 2Vs1 session, in which intensity was close to 80% HRmax. Moreover, while Duration (% of total time) with intensity > 85% HR max is close to 90% in all C¹ sessions, it only reaches 70% in the 2Vs1 session. This is probably due to the fatigue from the other games. Lactate levels follow the same pattern. While in all C¹ sessions, they range from 8.3 to12.4 mmol/l), in the 2Vs1 one they reach 7.3 mmol/l. Thus, there is a statistically significant difference in lactate levels between 1Vs 1+ ND ~2Vs1 ( p= 0.045<0.1).

Generally, lactate levels in C¹ are high, but there are differences depending on the addition of the extra player, his role and the restrictions on the rules. The highest values were observed in the 1Vs1 and the 1Vs1+1ND sessions. The same conclusion is also reached by Köklü, Aşçi, Koçak, Alemdaroğlu, & Dündar (2011), who found higher lactate levels in the 1Vs1 session as compared to the other small sided games.

Category 2 (C²)

According to the results, it seems that in the C² category, the average intensity is high (90-95% HRmax) in the 2Vs2, 2Vs2 +1 ΝΑ, 2Vs2 +1 ND sessions, while there is a statistically significant difference between the 2Vs2 ~ 3Vs2 ones. This difference is probably attributable to fatigue, which is clearly shown by the lactate level in the first three sessions (9-9.4 mmol/l) as compared to that in the last one (3Vs2), where it only reached 6.9 mmol/l.

Thus, the effects might have been different had the order of the sessions been different, which, in turn, can be the subject matter of a future research. Another factor that probably affected the high intensity of the session is the players’ technical and tactical level, since the more the players that participate in a session, the more difficult the attack and defense collaboration among them becomes, resulting in a decrease in intensity. In agreement with Clemente, Couceiro, Martins, Mendes (2012), the present study suggests the number of players in small sided games be increased progressively, depending on their learning and specialization phases. Fewer players are recommended for lower level practice, with more players being added as this level improves.

Overall, the present study concludes that C¹& C² category sessions have a high intensity (from 90% to 95% HRmax), and a high Duration with intensity > 85% HR max, (from 85% to 95% of total time). The extra player’s presence and the change in his role kept intensity high. It is therefore evident that increasing the number of players while keeping the SGG dimensions constant in the C¹& C² category sessions does not necessarily decrease intensity as has been claimed (Rampinini et al., 2007; Owen et al., 2004), but this depends on the way that the player participates in the game. Therefore, these sessions can be deemed ideal for improving aerobic / anaerobic capacity. The finding from the 2Vs1 & 3Vs2 sessions shows that exercise characteristics (total quantity – repetitions, duration, recovery etc) in SSG with a small number of players must definitely be adapted to these players’ fitness and technical-tactical levels. The results might be different in professional soccer players who, according to Dellal et al. (2011) cover longer distances with high intensity as compared to amateurs.

The high intensity generated in sessions with a small number of players (Rampinini et al., 2007) is probably attributable to more ball contacts per player, which requires greater energy expenditure (Reilly, & Ball, 1984). However, at the same time, we believe that this could also be attributable to the more active participation from the players who do not possess the ball, as the smaller the participants’ number is, the more frequent and necessary an offensive or defensive action and collaboration becomes.

CONCLUSIONS

C¹ & C² small sided games training can help soccer players practice their attack and defense technical-tactical skills in order to cope with real game conditions and also improve their aerobic and anaerobic capacity.

The players’ technical-tactical and physical skills along with the role of the additional player interact and determine the quality of the small sided game. The present study agrees with Clemente et al. (2012), Rampinini et al. (2007), and Little & Williams (2006) and concludes that many factors need to be considered so as to devise a small sided game training scheme. These factors are the players’ technical level, tactical knowledge, intelligence and physical abilities, along with the recovery time, the field, and the difficulty level, which must be adapted to the rules and the goals set by the coach. It is obvious that thorough knowledge of each category’s technical-tactical and physiological characteristics assists the coach in devising the most appropriate scheme to maximize player performance.

Finally, in agreement with a study by Hill-Haas et al. (2011) which strongly recommends that small sided games should be applied in order to improve training quality and specificity, the present study suggests all C¹ & C² category sessions should be implemented so that contemporary SSG training becomes more complete, more mentally demanding and more realistic.

References

Capranica, L., Tessitore, A., Guidetti, L., & Figura, F. (2001). Heart rate and match analysis in pre-pubescent soccer players. Journal of Sports Sciences, 19, 379-384.

Casamichana, D., & Castellano, J. (2010). Time-motion, heart rate, perceptual and motor behaviour demands in small-sides soccer games: Effects of field size. Journal of Sports Sciences, 28(14), 1615-1623.

Clemente, F., Couceiro, S.M, Martins, L.F., & Mendes, R. (2012). The usefulness of small-sided games on soccer training. Journal of Physical Education and Sport, 12(1), 93-102.

Coutts, A.J., Rampinini, E., Marcora, S.M., Castagna, C., & Impellizzeri, F.M. (2009). Heart rate and blood lactate correlates of perceived exertion during small-sided soccer games. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 12(1), 79-84.

Dellal, A., Chamari, C., Pintus, A., Girard, O., Cotte, T., & Keller, D. (2008). Heart rate responses during small-sided games and short intermittent running training in elite soccer players: A comparative study. J Strength Cond Res, 22, 1449-1457.

Dellal A, Hill-Haas S, Lago-Penas C, & Chamari K. (2011). Small-sided games in soccer: amateur vs. professional players’ physiological responses, physical, and technical activities. J Strength Cond Res, 25, 2371-2381.

Dellal A, Jannault R, Lopez-Segovia M, & Pialoux, V. (2011). Influence of the Numbers of Players in the Heart Rate Responses of Youth Soccer Players Within 2 vs. 2, 3 vs. 3 and 4 vs. 4 Small-sided Games. Journal of Human Kinetics, 28, 107-114.

Grant, A., Williams, M., Dodd, R., & Johnson, S. (1999a). Physiological and technical analysis of 11 v 11 and 8 v 8 youth football matches. Insight, 2, 3–4.

Grant, A., Williams, M., & Johnson, S. (1999b). Technical demands of 7 v 7 and 11 v 11 youth football matches. Insight, 2, 1–2.

Helgerud, J., Engen, L. C., Wisløff, U., & Hoff, J. (2001). Aerobic endurance training improves soccer performance. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 33, 1925–1931.

Hill-Haas, S., Dawson, B., Coutts, A., & Rowsell, G. (2008). Physiological responses and time-motion characteristics of various small-sided soccer games in youth players. J Sports Sci, 10, 1-8.

Hill-Haas, S., Coutts, A., Rowsell, G., & Dawson, B. (2008). Variability of acute physiological responses and performance profiles of youth soccer players in small-sided games. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 11(5), 487-490.

Hill-Haas, S.V., Dawson, B., Impellizzeri, F.M., & Coutts, A.J. (2011). Physiology of small sided games training in football: a systematic review. Sports Med, 41, 199-220.

Impellizzeri, F. M., Marcora, S. M., Castagna, C.,Reilly, T., Sassi, A., Iaia, F. M., & Rampinini, E. (2006). Physiological and performance effects of generic versus specific aerobic training in soccer players. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 27, 483-492.

Jones, S., & Drust, B. (2007). Physiological and technical demands of 4 v 4 and 8 v 8 games in elite youth soccer players. Kinesiology, 39(2), 150-156.

Katis, A., & Kellis, E. (2009). Effects of small-sided games on physical conditioning and performance in young soccer players. Journal of Sports Science and Medicine, 8, 374-380.

Kelly, D.M., & Drust, B. (2009). The effect of pitch dimensions on heart rate responses and technical demands of small-sided soccer games in elite players. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 12, 475-479.

Köklü, Y., Aşçi, A., Koçak, F.U., Alemdaroğlu, U., & Dündar, U. (2011). Comparison of the physiological responses to different small-sided games in elite young soccer players. J Strength Cond Res, 25(6), 1522-8.

Little, T., & Williams, A.G. (2006). Suitability of soccer training drills for endurance training. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 20, 316-319.

Little, T., & Williams, A.G. (2007). Measures of Exercise Intensity During Soccer Training Drills With Professional Soccer Players. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 21(2), 367-371.

Mallo, J., & Navarro, E. (2008). Physical load imposed on soccer players during small-sided training games. The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness, 48(2), 166-171.

Owen, A., Twist, C., Ford, P. (2004). Small-sided games: the physiological and technical effect of altering pitch size and player numbers. Insight. 2(7), 50-3.

Platt, D., Maxwell, A., Horn, R., Williams, M., & Reilly, T. (2001). Physiological and technical analysis of 3 v 3 and 5V5 youth football matches. Insight 4(4), 23-24.

Rampinini, E., Impellizzeri, F. M., Castagna, C., Abt, G., Chamari, K., Sassi, A., & Marcora, S. M. (2007). Factors influencing physiological responses to small-sided soccer games. Journal of Sports Sciences, 25(6), 659 -666.

Reilly, T. & Ball, D. (1984). The net physiological cost of dribbling a soccer ball. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 55, 267-271.

Reilly, T., & Brooks, G.A. (1986). Exercise and the circadian variation in body temperature measures. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 7(6), 358-362.

Rudolf, P., & Václav, B. (2009). Heart rate response and game-related activity of younger school-age boys in different formats of soccer game. Movement and Health, 1, 69-73.

Williams, K., & Owen, A. (2007). The impact of player numbers on the physiological responses to small sided games. Journal of Sports Science and Medicine, 6(10), 100.