Keywords: Technique training, methodology, softballs, special rackets and balls, basic technique, instant tennis.

Method

Participants

The sample comprised 90 coaches aged from 18 to 52 years. The average age of the sample was 30 years old. 63.4 % were men and 36.6 % women. 87.4 % were former athletes. In terms of profession, 8.2% were full-time coaches with services slip. The majority (91.8%) was part-timers, without contract and insurance. In terms of education, 18.0 % of the coaches were holders of diplomas from the General Secretariat for Sports. The level of education of the sample had the following characteristics: 2.2 % Primary School, 1.1 % 3-Seat Gymnasium, 4.5 % General Education High School, 1.1 % Technical Trade School, 2.2 % lower school CHTPE- TEI (Centres of Higher Technical Professional Education - Technical Institutes of Education), 75.3 % Higher Education Degree DFESS (Department of Physical Education and Sport Sciences), 7.9 % have a postgraduate degree, 4.5 % a master's degree, 1.1 % a Ph.D.

Procedure

The method used to determine the characteristics and the training methods of the Greek Tennis coach was based on the use of a questionnaire. In the research, 90 coaches from all parts of Greece completed the questionnaire. The whole range of Greek tennis coaching was represented, with participants coming from every category. Part-time and full time coaches, empirical coaches and gymnasts. The questionnaire records the opinions of the coaches in relation to the technique they teach and the training methodology they follow. Technique training referred to the basic strokes forehand, backhand, volley, serve and overhead. Training methodology referred to instant tennis, to the use of special rackets and balls during training and to the required time for the teaching of the basic technique.Results

Methodology of Technique Teaching

In order to find out whether the Greek coaches practice a common methodology in teaching the basic strokes (forehand, backhand, volley, serve, and overhead), a homogeneity analysis (correspondence) was carried out. The first three axes of this analysis include 60.97 % of the total variance. In the first axis we have the differentiation between the variables evidence the use of the Eastern Grip in Volley, Serve and Overhead strokes, and the variables evidencing that the Continental Grip is used in Volley, Serve and Overhead strokes. In the second axis, we have an opposition of Eastern and Western mainly with regard to the Overhead, Serve and Backhand variables, and more generally with the other variables. In the third axis, the opposition of Western and Continental in Forehand and Backhand variables is noticed.Diagram 1

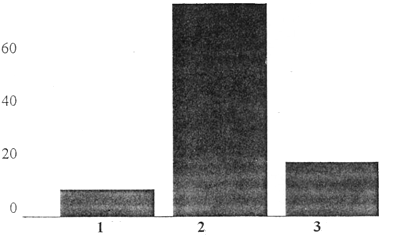

Relative frequency of the grip used by coaches for forehand strokes.

Notes: 1. 10 % use the Continental grip.

2. 72.2 % use the Eastern grip.

3. 17.8 % use the Western grip.

Diagram 2

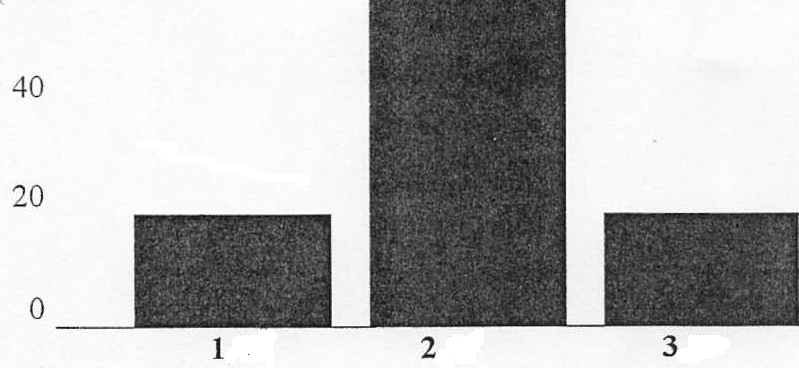

Relative frequency of the grip used by coaches for Backhand strokes.

Notes: 1. 20.2 % use the Continental grip.

2. 59.6 % use the Eastern grip.

3. 20.2 % use the Western grip.

Training Methodology

Instant Tennis, special rackets and balls. In order to establish whether Greek tennis coaches adopt a clear and common direction in terms of training method (instant tennis, use of special rackets and balls at an initial teaching level), we used a respective questionnaire for the factorial analysis and the clustering. In the homogeneity analysis (correspondence), we note the differentiation of variable from the rest, and in the second axis, each two correlated groups of variables are formed and opposed to each other. On one hand, the variables are stating the use of special rackets and balls and on the other hand, the ones stating the use of instant tennis with limited in time teaching of basics.Carrying out the grouping of the correspondences results, we have the following Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1. Results of the factorial analysis of correspondences of the "Basic strokes technique methodology" data table

|

3.1 Forehand Tech |

1 st factor |

2nd factor |

3rd factor |

||||||

|

Which of the following grips do you use more often |

Co-ordinates |

Absolute participation of axis |

Cosinus squared |

Co-ordinates |

Absolute participation of axis |

Cosinus squared |

Co-ordinates |

Absolute participation of axis |

Cosinus square |

|

Continental |

-01 |

.0 |

.00 |

-36 |

.6 |

.01 |

2.12 |

34.9 |

50 |

|

Eastern |

.25 |

2.1 |

.16 |

.21 |

1.6 |

.11 |

-0.4 |

.1 |

.00 |

|

Western |

-1.01 |

10.3 |

.22 |

-64 |

3.7 |

.09 |

-1.02 |

14.4 |

.22 |

|

3.2. Backhand Tech. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Continental |

07 |

.0 |

.00 |

-58 |

3.6 |

.09 |

.93 |

14.2 |

.23 |

|

Eastern |

.19 |

1.0 |

.05 |

.49 |

7.0 |

.34 |

.11 |

.5 |

.02 |

|

Western |

-64 |

3.7 |

.10 |

-82 |

6,7 |

1.7 |

-1,29 |

26.1 |

.42 |

|

3.3. Volley Tech. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Continental |

.21 |

.18 |

.37 |

-13 |

.7 |

.13 |

-0.2 |

.0 |

.00 |

|

Eastern |

-1.71 |

14.8 |

.37 |

1.03 |

5.9 |

.13 |

20 |

.3 |

.00 |

|

3.4. Service Tech. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Continental |

.35 |

4.7 |

.71 |

.06 |

.1 |

.02 |

-10 |

.7 |

.06 |

|

Eastern |

-2.49 |

22.0 |

.52 |

1.65 |

10.6 |

.23 |

.03 |

2.4 |

.03 |

|

Western |

-1.55 |

7.3 |

.17 |

-2.68 |

23.9 |

.51 |

.57 |

1.7 |

.08 |

|

3.5. Overhead Tech. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Continental |

.34 |

4.4 |

.57 |

.16 |

1.0 |

.13 |

0.9 |

.6 |

0.4 |

|

Eastern |

-3,43 |

23.8 |

.55 |

2.32 |

11.9 |

.25 |

.00 |

.0 |

.00 |

|

Western |

-1.06 |

6.3 |

.16 |

-1.93 |

22.6 |

.52 |

.64 |

3.9 |

0.6 |

Table 2. Results of the grouping of the data table of the third unit "training methodology"

|

Group |

During learning stages |

Evaluation Test |

Coaches |

|

Class 1 |

Use special balls (Tech 7) |

-3.89 |

30 persons |

|

|

Special rackets (Tech 6) |

-3.89 |

|

|

|

How much time do the athletes need (Tech 5) |

-4.46 |

|

|

|

Instant tennis-It is efficient (Tech 2) |

-6.08 |

|

|

Class 2 |

Instant tennis-It is efficient (Tech 2) |

5.04 |

27 persons |

|

|

How much time do the athletes need (Tech 5) |

3.77 |

|

|

|

Use special rackets during initial4earning stages (Tech 6) |

-3.83 |

|

|

Class 3 |

Use special rackets during initial earning stages (Tech 6) |

7.48 |

33 persons |

|

|

Use special balls during initial learning stages (Tech 7) |

5.72 |

|

Discussion

Considering the results of the research, it is clear that coaches do not have a common methodology in terms of technique teaching and a clear direction in terms of training method. Three classes (groups) of coaches derived from the grouping analysis.References

Argiriadou, Ir., Mavrovouniotis, F., Pelekoudas, A., Kougioumtzidis, H., & Sofiadis, N. (1998). Opinions of handball athletes with regard to their psychological state and performance. Third European Conference in Adapted Physical Activity, 16-18/10/1998, Thessaloniki, pp. 149 (abstract).

Arranz, A., Andrade, J. C., & Grespo, M. (1993): Tennis 1 & 2. RFET. Comité Olympico Espanol.

Brown (1983): The L. S. U. Basketball Organisational Handbook. New York: Leisure Press.

Fairweather, M. (1999). Skill learning principles: implications for coaching practice. In N. Cross, & J. Lyle (Eds.), The Coaching Process: Principles and Practice for Sport (pp. 113–129). New York: Butterworth Heinemann.

Grespo (1977). The Role of the Tennis Coach European Coaches Symposium Tennis. Makarska Croatia.

Lawn Tennis Association (2005). Ariel mini tennis-teachers and coaches Information. Available from URL: http:// www.mini-tennis.com/teachers_coaches.htm

Laios A. (1994). The Coach and Management. Thessaloniki: Salto.

Labar, Ρ. Ε. (1982). Learning Tennis Together. New York: Leisure Press.

Martens, R. (1987). Coaches Guide to Sport Psychology. Champaign IL: Human Kinetics.

Papachristou, A. (1987). Tennis Programming and Administration of Education. Arta Tahidromos-Philipiada.

Peter,T., & Austin, N. (1990). Passion for Excellence. The Leadership Difference. Great Britain.

Profetis, G (1993). Introduction to Management. Profit and People. EKVE. Thessaloniki.

Quezada, S., Riquelme, N., Rodriguez, R., & Godoy, G. (2000). Mini tennis. Coaches Review, 1, 21-24.

Ruth, J., & Le Bar, B. (1982). Learning tennis together. New York: Leisure Press.

Real Federation Espana Tennis (1993). Tennis 1 & 2. Comité Olumpico Espanol.

Schmidt, R. (1983). Motor Learning and Performance: From Principles to Practice. Athens: Athlotipo.

Soulandros, B. (1987): Simple MotivationModel. National Centre of Public Administration. Athens.

Swedish Way. (1993). Swedish Tennis-Association. European Coaches Symposium Tennis. Rome.

Tennis Coaches Australia (2002). Development coaching manual: Tennis coaches. Richmont: Australia.

Thorpe, R., & Bunker, D. (1982). From theory to practice: Two examples of an understanding approach to the teaching of games. Bulletin of Physical Education 18, 9-15

Van der Meer, D. (1982). Completely Book of Tennis. New York: Butterworth Heinemann.