Fiore dei Liberi : Origins and Motivations

Journal of Western Martial Art

July 2008

by Russ Howe

Introduction

In the pantheon of history, Fiore della Liberi or Fiore dei Liberi, is a minor figure, one not (yet) found on university curricula, absent from texts discussing medieval Italy, and, frankly, one who failed to make even a ripple on the turbulent ocean of the Middle Ages. Yet in the growing field of Western martial arts, he is a giant, whose Flos Duellatorum or Fior Di Battaglia is the oldest and most complete document of its type. The fighting system he recorded, apparently for the benefit of Niccolo III d'Este, is complex and beautiful in its efficiency and symmetry. The artwork is clear, the instructions direct, and the lessons valuable. While the fighting system itself is the subject of many dynamic projects, little has been uncovered about the author of this fascinating work.

|

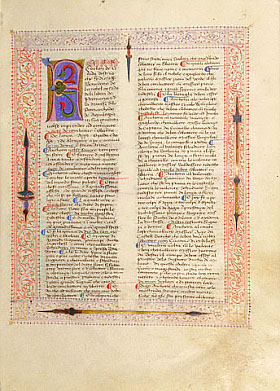

| The first page of the prologue found in the Getty's version of Flos Duellatorum. MS. LUDWIG XV 13. |

What is known about Fiore della Liberi has been extracted from the Prologue of the treatise. Based on the limited details in the Prologue on the "man" behind Fiore, we know that he styled himself as Fiore della Liberi of Cividale of Austria of the diocese of Aquileia, son of Sir Benedetto, a modest noble family of the House of Dei Liberi from Premariacco, a tiny village still in existence today, and situated approximately 15 km SW from Cividale all of which resides in what was known as the Friulian District. However, much can be learned from the world around him, both during his formative years and later when he was writing his masterwork. While the period in question is six centuries behind us, the documents available and scholarship on both the era and region offers us a great deal of material from which we can draw plausible conclusions about Fiore. His origins and a number of the whys and wherefores of his life are open but answerable questions. The hotly contested issue of his ethnic or cultural background can also be examined in its historical context, and a solution formulated. There is also copious evidence available to understand both his motivation for leaving Premariacco and for trying to build his reputation in Ferrara.1

Limitations of the Sources

While quality materials are available to assist our analysis, there are significant limitations to these. First, this article is limited to sources in English. Second, there are limitations related to Fiore himself. We have no precise date for the birth or death of Maestro Fiore, although a birth date in the middle of the fourteenth century (1350 to 1360) seems most likely, based on a dating of his book to c. 1410, and his self proclaimed practice of arms for some forty years. We have no evidence whether our subject had a wife, children, or siblings, nor any real details of his material success or lack thereof. We cannot even say with certainty that the author's real name was Fiore. So while some facets of what we think we know about the master become clearer upon examination, other parts of his life become less certain as we are forced to put aside some of our previous assumptions about the man.2

For the purposes of this paper, the reader is assumed to have a basic knowledge of Fiore della Liberi and the three extant versions of his Fior Di Battaglia or Flos Duellatorum. No effort will be made to explain the similarities and differences between and among the Getty, Morgan and Pisani-Dossi versions of Fiore's work. The interested reader can find these discussions pursued with vigor and discipline in a number of books, articles and websites. Nor is there space here to properly explore Fiore's apparent appearances in Udine, Padua, etc. These tantalizing mysteries will have to be left to further research. It is also assumed that the reader has at least a cursory understanding of the medieval geography of the region.3

With these cautionary notes sounded, we may turn to our exploration of the life and world of the man known as Fiore della Liberi.

The Basics

Fiore's origins lay in what is now the extreme northeast of Italy, in the town of Premariacco, in the duchy of Friuli in the diocese of the Patriarch of Aquileia. The area was a crossroads of cultures and jurisdictions from early imperial Rome and remained so in the Middle Ages.4 That this region eventually became part of modern Italy seems to be the improbable outcome of the Austrian-Hungarian imperial hunger for an outlet to the sea at Trieste, combined with the rather cynical redrawing of the map of Europe at the end of World War I. Geographically and historically Aquileia-Friuli could just as logically form part of Austria, Hungary, Slovenia, Serbia or Dalmatia as Italy. This confluence of cultures leads to some difficulty in teasing out information about Fiore.

Fiore came from a minor noble family of the region, a status most easily equated to a free knight with small holdings. We can derive this information from his name, Della Liberi. Like most medieval second names, it had a functional purpose, to identify the occupation or social class of the holder amongst his fellows.5 It seems clear that Liberi is a reference to one of the two types of knights in German who held land, the liberi and the ministeriale.6 The term liberi refers to a free class of knights, while ministeriale is the term for the class of German knights who were "unfree" in their origins and thus could not marry without their lord's permission and could be bought, sold or donated in a will or as a gift.7 Although over time the status of the ministeriale evolved (and the liberi ceased to exist) the importance of this distinction, and how the Habsburgs dealt with both types of knights, can provide evidence for Fiore's motivation to leave Friuli and eventually to settle in Ferrara.

Maestro Fiore claims in his text to have both written and illustrated the work. If we accept this at face value (and there may be reason to) that means that Fiore was literate in both Latin and Italian. This would be consistent with a quality education for a minor noble of the period. Fiore trained under German masters, traveled in Germany, and trained a number of German students of some prominence, so we can either conclude that the German masters and students communicated with Fiore in Latin, or Fiore spoke German. It seems more likely that Fiore spoke German in addition to his fluency in Latin and Italian. There might be some argument that the Latin portion of the writings were written or translated by another individual, but since there is no evidence for this, and Latin literacy was not uncommon among men of his social standing in Italy in this period, we can reasonably conclude that Fiore was fluent in Italian, Latin and German.

It also appears that Fiore was a man of substantial means. He describes his significant travel over the years of his training, the significant expense associated with the development of his skills. For a man to travel to the extent that Fiore did in Germany and Italy and to pay the best masters in Europe for training would require a reasonable level of affluence. With this established, the more complex and substantive issues of Fiore's origins, ethnicity and motivations can be explored.

The Competing Theories

Discussions about the ethnic or national origins of Fiore have taken place in a number of forums. Theories have been proposed in print, on the internet, at Salles and Academies, and the topic discussed anywhere those with an interest in Western martial arts gather. These theories include:

1. Fiore was Italian

2. Fiore was Austrian.

3. Fiore was Dalmatian or Slovenian

4. Fiore was German.

5. Fiore was a graduate of the University of Vienna.

While the manuscripts themselves do not allow us to definitively either accept or reject any of the above theories (and some are not mutually exclusive), a careful review of the history of the region of Fiore's origin, combined with what can be learned from the manuscripts can allow us to reach some probable conclusions about his ethnic and social origins.

A Brief Analysis of the Cultural History of Aquileia, Friuli and Cividale

The patriarchy of Aquileia has clear and unequivocal roots in the classical era. The colony of Aquileia was founded in 181 BC at the extreme edge of what would later be considered Italia proper.8 Aquileia sat astride the joining of Italia and the provinces of Noricum, Pannonia and Dalmatia. The original inhabitants were a mix of Romans and southern Celtic tribesman who were friendly with the Romans.9 The location was carefully chosen to provide access to the southern Alps and facilitate eventual expansion in the east.10 However, the key strategic position, while making it an ideal launch point for military campaigns, placed it in a vulnerable position for aggressive invasion.

In AD 171 a barbarian invasion swept through Transdanubia, Styria and Carnolia and culminated with an attack on Aquileia. It took the emperor Marcus Aurelius a campaign of eight years to drive them out, and the devastation to the Roman lands was severe. The defenses along the Danube were strengthened to prevent a further incursion but there were inadequate resources to repopulate and rebuild. The emperor's solution was to invite in friendly German tribes to repopulate the area and reconstruct the ruins.11 This was the earliest use of German tribes to provide population inside the empire proper, and it significantly altered the ethnic makeup of the region. Thus, there had been German influence in the area of Aquileia for more than a thousand years before the birth of Fiore della Liberi.

The town of Cividale also had a classic origin. The town was originally founded by Julius Caesar, who in his typical modesty named the town after himself, Forum Iulii, which later became the town Cividale.12 The origin of Friuli is less apparent, but it is certain that by 590 (or before) Friuli was a Lombard duchy.13 Aquileia, Friuli and Cividale were to fall under "German" rule from the time of Charlemagne forward, and Friuli remained loyal to its German allies. When the Germans and Lombards struggled against an Avar invasion, Erich, Margrave (a title referring to a lord or military governor of a medieval German border province) of Friuli, crossed the Danube and stormed the capital of the Avars in support of his German compatriots.14

In 951 Otto, King of the Franks, successfully defended this territory in a campaign against the Italian king Berenger.15 At the Diet at Augsbeg, which followed in 952, Otto revived the duchy of Friuli in favour of his brother Henry and included in this new duchy the margravates of Istria, Aquileia, Verona and Trent.16 Nonetheless, Bavaria remained Henry's power base, and the Patriarchs of Aquileia and other feudal lords of the region were appointed from Bavaria for about the next 300 years.17 Henry immediately stamped his authourity on the region by having the rebellious Patriarch of Aquileia castrated in 955 for supporting the Pope against the emperor.18

|

| The Holy Roman Empire during the tenth century. The march of Carinthia is the central portion of the collection of Bavarian marches hatched in purple in the lower right. (source: wikipedia.org) |

In 976 Carinthia was separated from Bavaria and established itself as a mark or march (an area defined with its own localized dynasty and sub-divided into counties, having some level of autonomy), and in the eleventh century it annexed Istria, Friuli (which included Aquileia and Cividale) and the Verona district.19 From this time forward the Aquileian patriarchate had significant political and military significance in German affairs since the incumbent claimed overlordship of the march of Carnolia and also owned large estates in the German kingdom proper, a legacy from Henry of Bavaria. Until the see was transferred to Venice in 1451 the patriarch was usually a German nobleman.20

The right to strike coinage was given to the Patriarchs of Aquileia in the ninth century, and from the eleventh century to the fifteenth they struck a long series of denars.21 The German denars were introduced to Austria shortly after the battles between the Germanic and Hungarian rulers, ultimately being phased out in favour of the pfennig. The Italian equivalent was the denaro but this was not produced at the mint at Aquileia. The only other numismatic evidence relevant to the present inquiry is that while the mint at Aquileia was striking German coins, a number of German mints struck coins that carried a representation of the Patriarch, that being an eagle with wings displayed. This interaction reinforces the conclusion that the region was intimately tied to the German principalities, their commerce, and economics.

In 1076 the march of Friuli was bestowed upon Sieghard, patriarch of Aquileia to reward him for his desertion of the papal cause (a wise decision considering his predecessor's fate for making the opposite choice).22 The patriarchy of Aquileia and march of Friuli remained the feudal property of the crown of Bavaria until the fateful clash between Ottokar II and Rudolf I, Habsburg Duke of Austria and later Holy Roman Emperor where he (Ottokar II) was defeated by Rudolph and killed at the Battle of Dürnkrut and Jedenspeigen on the March on August 26, 1278.

A brief aside is required to highlight the importance of the political development of the patriarchy of Aquileia on relations between the German church and nobility. The ratio of church holdings to lay holdings was significantly higher in Germany in the Middle Ages than in another other regions of Europe (with the exception of the Papal States). The power of the higher clergy was significant, and they were often as active and cunning in their acquisition of land and income for the church as the most avaricious of nobleman were for their families. Before the declarations and enfeoffment of Friuli to Sieghard of Aquileia in 1077, they caused significant administrative and jurisdictional problems.

Before 1070 or so the law had effectively held that churchmen should not be exercising authourity over functions that were not related to the spiritual well-being of the community. The secular power of ducatus brought with it certain military authourity, taxation, minting and court authourity that up until the late eleventh century churchman could not exercise. In cases where dioceses in German lands had significant holdings that were secular in nature, the practice had grown up of the emperor or king appointing a noble "advocate" to administer the jurisdiction considered unsuitable for a clergyman. This institution was more notable for its abuses than its effectiveness, with money, land and titles being directed to the benefit of the advocate's personal holdings, his family or his lord. A number of dioceses were effectively impoverished by their advocates.

In the eleventh century Archbishop Adalber of Bremen and Patriarch Sigehard of Aquileia began to write of the temporal aspect of the higher clergy's authourity in ducal terms. The first clear instance of the bestowing of ductas upon a clergyman occurred when Henry IV enfeoffed Aquileia with the county of Friuli, the "temporalities" including appropriate jurisdictions, taxes, and law courts. This practice then spread to Bremen and Wurzberg, and later to Mainz, Cologne, Magdeburg, and Salzburg, forever altering the balance of power between the church and the princes (most particularly counts).23 Most importantly for our investigations, the transfer of ductas was confirmed for Aquileia and Friuli by German Imperial Charter before the practice spread into the other German jurisdictions, illustrating the close political and social ties between Friuli and the other German duchies.24 After Friuli received ducal rights in 1177, Aquileia itself was elevated to a dukedom in 1180, further expanding the temporal/secular powers of the Patriarch.25

A series of letters from Frederick Barbarossa in 1150 also verify the control of the German emperor over Aquilia as Frederick discusses with the Patriarch the nature of military obligations owed from a diocese to the emperor and bemoaning the lack of cooperation from other bishops in a campaign against Milan.26 There is significant further evidence of the German nature of the area found during the reign of Emperor Frederick II. In the spring of 1232 Frederick II traveled north from his winter quarters at Ravenna to meet with all the significant princes of Germany at Aquileia and Cividale. This historic meeting was not only a general assembly but was also convened to address the problem of northern cities trying to assert their independence from the feudal aristocracy. The key document to emerge from this gathering was the declaration of "the rights of our princes and magnates" issued at Cividale in 1232.27 Considering the politics and violence of the age, it is unlikely that the flower of German nobility would have gathered in a location where they did not feel both comfortable and safe. Aquileia and Cividale, having been part of the Holy Roman Empire for some 400 years, and being governed by nobility from Bavaria for three centuries would have been the perfect "Germanized" location.

A Brief Appearance by the Habsburgs

After the end of the Hohenstaufen dynasty in 1254, the future of the title of Holy Roman Emperor and the viability of the crown of King of Germany both seemed in doubt. The electors were jealous and fearful of their own privilege, and thus maneuvered to deliver both titles to nobles who were not powerful enough in their own right to use the platform to expand their holdings. At this point in time a remarkable Czech entered the center stage of medieval German politics, and his rise and fall would change the nature of central European politics and allow the region we are concerned with to fall under the domain of the Habsburgs.

In 1260 Otakar II of Bohemia defeated the King of Hungary and forced him to cede to Bohemia all of Styria and Austria.28 Shortly thereafter another German noble line failed to have an heir and Otakar thus gained Carinthia, controlling all of modern day Austria with the exception of the Tyrol.29 Finally in 1271 his appointed governor of Styria, Ulrich von Durnenholtz, conquered Carnolia and installed himself as captain-general of Friuli as well.30 On the eve of the election for the German crown Otakar's position in central Europe was unprecedented since the Carolingian era. His crown governed a well-administered territory stretching from the Sudeten Mountains to the shore of the Adriatic. He had also managed to unite under his authourity the northern Slavs (Czechs), the southern Slavs (Slovenes of Carniola) and many German speaking peoples (Austria, Styria and portions of Bohemia).31 It seemed unthinkable that the German electors would defy his claim to the overarching titles he sought.

Confident in the outcome, Otakar did not attend the gathering of the electors. Rudolf of Habsburg, a lord with significant but not overwhelming holdings in Alsace and Switzerland, did appear and executed a diplomatic masterstroke. Through a number of marriage alliances (later to become a Habsburg trademark), and by making territorial and religious concessions to the Pope (including a commitment to lead a sixth crusade and not to pursue imperial territorial ambitions in Italy) and alliances with relatives, he persuaded the electors to choose him as the next Holy Roman Emperor.32 Shortly thereafter, at the Pope's behest, the King of Germany, Alphonso X recognized Rudolf I's claims to lordship as well. Not surprisingly, Otakar II refused to recognize the election and conflict ensued alluded to earlier.

Rudolf was able to enlist significant allies and defeated Otakar in the first campaign, which ended in 1276 with his siege of and triumphant entry into Vienna.33 One of the keys to Rudolf's victory was the Austrian and Styrian ministeriale disavowing their allegiance to Otakar and opening key castles and strongholds to Rudolf as he marched across the region.34 This assistance from the ministeriale would not be forgotten by either Rudolf or later generations of Habsburgs, who credited the initial success of the Habsburg dynasty to the loyalty of Styrian and Austrian ministeriale, and a series of very astute marriage alliances. Both of these central characteristics of Habsburg dynastic ambition will be important in our analysis of the social position of Fiore and his family in Friuli when the Habsburgs returned to the region almost a century later. Immediately upon taking control of the regions noted above, Rudolf began to promote the interests of the ministeriale and to work feverishly to eliminate the liberi.

Otakar, who had managed to retain Bohemia, built a new coalition, including a number of Rudolf's former allies and Saxons, Poles, Bavarians, and others. This campaign can be seen as an early example of Slavic solidarity.35 The second campaign came to an end when Rudolf defeated Otakar at the battle of Durnkurt on August 26, 1278.36 Otakar himself was killed during the battle, apparently murdered during the retreat. The battle of Durnkurt shaped the history of central Europe for more than five centuries. Austria and Styria became heredity Habsburg lands in 1282 (rather than merely being ruled by imperial prerogative) and were ruled continuously by the Habsburgs until 1918.

But the Habsburgs were not to hold Friuli and its environs for long. The counts of Gorz had risen to prominence by their inheritance of Tyrol in 1253.37 Their original lands of Gorz, added to Tirol (a key crossroads of southern Europe), and strict utilization of the advocacy over the bishoprics of Trent and Brixen had made them a powerful family. There is evidence that they may have held the advocacy for Aquileia for some time before 1286.38 The Gorz were staunch allies of Rudolf in his war with Otakar and were rewarded with the duchy of Carinthia and dominion of Carnolia for their loyalty in 1286.39 This grant included Friuli and its environs, once again coming under the control of a German family. But to better understand the region's influence on Fiore, we must turn away from a chronology of the control of the region and examine two broader social topics that will help us understand Fiore's place in the medieval world.

Liberi and Ministriale

The social structure of medieval Germany had a great many similarities to, but some crucial differences from, the better-known English and French structures. At the top of the hierarchy (at least in the early and high medieval periods) were the King of the Germans and the Holy Roman Emperor. Below them were situated the higher nobility commonly referred to in the historical literature as the princes or magnates. This would include dukes, counts, barons, margraves, and others who would hold substantial lands and have further vassals beneath them. For practical purposes this magnate class would (at least in Germany anyways) include higher members of the clergy, bishops, patriarchs, etc. The final strata of the nobility were the knights or milites, the equivalent of signori in Italian. It is from this class that Fiore della Liberi originates, and through its evolution and tensions we can seek to better understand the man.

Unlike their French and English counterparts, the milites did not form an undifferentiated social class. At least in theory, the milites liberi, or free knights, were the social superiors of the milites ministeriales, or unfree knights.40 The liberi were nobilis, that is part of the ordo nobilis, or order of nobility, while the ministriales were not and formed their own, non-noble, indentured order.41 While the liberi owed duties and obligations to their feudal superiors, they held their own land (which they could pass down to their children), could marry freely, and had the status of free men under the law. They functioned very much like the common concept of knights in the Western media.

The ministriales were knightly in function but unfree in status. Whereas liberi were free men constrained by the contractual nature of vassalage, ministriales were not free men, and their service was an ineluctable duty to the lord upon whose patrimony and into whose ownership they were born. .42

Throughout the Middle Ages they are found documented in the same retinues with liberi,43 but steadily between the eleventh and fourteenth century the ministeriale were to supplant and eventually replace the liberi.44 This does not appear to have occurred due to any hostility between the two groups and in fact there are many references to the retinues of a single lord or large armies being composed of both types of knights. The effective extinction of the liberi class instead came about due to the actions of the magnates or princes who preferred the ministerale over the liberi for their own purposes. While liberi had certain rights in the feudal structure that granted them certain advantages and powers, along with the multigenerational control of lands, there were no such restrictions with the unfree ministeriale. It appears that the magnates engaged in an intentional campaign to reduce the liberi class and eventually fill all of the milites positions, and even many higher offices, with ministeriale.45

The extinction of the liberi class was achieved through a number of methods. When liberi families produced no heirs, their lands were then assigned to ministeriale rather than free men. Laws were passed that declared the children of a mixed union of liberi and ministeriale to be ministeriales. The most loyal of a magnate's serfs, and others who were worthy of recognition and reward, were elevated to the ministeriale class, rather than the liberi. Oppressive head taxes were applied to the liberi and not the ministeriale, which in many areas impoverished the liberi, forcing them to ‘voluntarily' accept ministeriale status when they renewed their feudal vows or debt imperiled their family holdings.46 The ministeriale class provided a politically viable solution for the indiscretions of the princes. Children who were born from the union of magnates and their often non-noble affairs could be raised to the ministeriale class. This allowed the princes to provide for their bastard children while not offending the sensibilities of other free nobles by giving them positions above their illegitimate status or permanently transferring valuable lands.47 These methods were so effective that by the thirteenth century the liberi were a small minority and rapidly dying out, and it appears that they effectively ceased to exist as a social class through intermarriage sometime in the fourteenth century.48

The motivations for the successful attempts to eliminate the liberi are fairly straightforward. Where liberi held wealth independently, the lands held by the ministeriale remained part of the wealth of the magnate. Profit could me made and alliances built through the directed marriages, sale or bequeathing of ministeriale at the right time with the right people. ministeriale were considered less likely to rebel, particularly when milites had to be send into a distant holding, such as the imperial properties in Italy.49 Finally, one could create and land ministeriale quite rapidly when the situation required, allowing the magnates to build up large armies, which were essential in Germany in these centuries, without alienating lands over the long term.50 While in some situations, groups and particularly influential single ministeriale would rise in open rebellion or defiance of their lord, overall the spread of the ministeriale and extinction of the liberi was to the princes' political and economic advantage.

For the purposes of our analysis it is important to note that the Habsburgs were among the most aggressive families promoting ministeriale over liberi, resulting in the earlier extinction of the liberi in Austria and Styria than in most other places.51 There were three reasons for this. First, as noted earlier, the ministeriale of these regions opened their castles to Rudolf, abandoning Ottakar II, which was crucial to Habsburg success. Thus there was a certain natural tendency to reward this group. Second, since the Habsburg alodial lands were in Switzerland and Alsace, the liberi of their new German holdings did not have significant bonds to the family, and thus under feudal law it would have been difficult for the Habsburgs to exert effective control over the local liberi. Their position as Holy Roman Emperors would allow Rudolf and his successors to maintain complete legal control of the ministeriale in their new possessions. Last and most important, control of the marriages of the ministeriale under feudal law allowed the Habsburgs to build alliances and acquire control over land by strategic marriages. While most medieval rulers made political use of marriages, this was arguably the most effective weapon in the Habsburg arsenal, and they used it to expand their power base more effectively than any other family in European history. While the Habsburgs were clearly capable of winning key battles and campaigns, their chief method of dynastic expansion over a period of some six centuries was the judicious use of marriages.52

The Origins of Austrian Nationhood

Fiore della Liberi's reference to "Ciuda d'ostria" or "Civida of Austria" in the prologues to his treatise has led many to assert that Fiore della Liberi was an Austrian by origin. However, the opinions of many on this subject have been coloured by the modern concept of the nation of Austria, which of course did not exist in its current form at the time of Fiore's birth in the mid-fourteenth century. In order to assess the assertion that Fiore may have been Austrian in origin, we must understand the nature of Austria, and the Habsburg holdings at the time of Fiore's birth and just before.

What we now call Austria first came into existence as a march in the eastern regions of the Empire, created as a military buffer against potential invaders from what is now Hungary and areas even farther east.53 The first documentary reference to the region as a whole is found in a document where it is referred to as "regione vulgari vocabulo ostarrichi" or "the area commonly known as Austria" in a grant in 996.54 The area was brought together as a single mark in 976 when the emperor bestowed the lands upon the capable Babenburg family, who would rule over Ostarrichi for the next 270 years.55 It is sometimes challenging to follow the development of this march as it was often referred to in Latin as ‘provincia orientalis', ‘terra orientalis', or sometimes simply ‘oriens'. To add to the confusion it was also referred to as ‘Marchio Liutpold' after its first ruler, the Margrave Leopold.56

Over the years, the mark expanded in size and became a bulwark against the Magyars (Hungarians). In 1156 the margravate was elevated to the dignity of a duchy with significant independence from the empire. The new Dukes of Austria were exempted from all dues except attendance at the Imperial Diets, and their military obligations were effectively only to defend their borders at the direction of the emperor.57 In 1192 the sister Duchy of Styria was added to the Babenberg holdings, and it effectively became a unofficial monarchy.58 In fact, some fifty years later there was talk of turning the Duke of Austria and Styria (note the ongoing clear separation of the duchies in question) into a king, and Duke Frederick II was said to have received a royal ring from the German emperor of the day, yet was never crowned a king.59 In 1246 Duke Frederick was killed at the battle of Ebenfurth fighting against the Hungarians, and he was the last male of his line.60 King Ottokar II of Bohemia was to be the next ruler of Austria and Styria.

What must be understood from the evolution of this region is that by the time of the birth of Fiore della Liberi, Austria was a central/southern German duchy and did not show any of the earmarks of the nation-state it was to become. In fact if one considers the mixed ethnic nature of the holdings of Ottokar II and later the Habsburgs, the development of a national consciousness came much later to Austria than regions such as France, England, Spain, or perhaps even Prussia. The Habsburgs were certainly not solely associated with their holdings in Austria and would not be identified that way, either in their own writings or those of contemporaries. The key point here is that Austria remained a local administrative division with no particular extra-territorial jurisdiction or imperial aspirations. There is simply no reason to believe that Fiore della Liberi or his contemporaries would have considered him an "Austrian" if he were indeed born in Friuli as the prologue of his works claim. We must further examine the history of the period and the different theories surrounding the "Civida of Austria" claim to unravel the mystery of the origins of Fiore della Liberi.

The Gorz/Tyrol Dynasty and Early Habsburg Policy South of the Alps

As was noted above Rudolf of Habsburg had consolidated power in the area we are concerned with in the German family of Gorz early in his reign. The counts of Gorz had already risen to some prominence as advocates of the Patriarch of Aquileia in the twelfth century and like other Bavarian dynasties (such as the Andechs and Ortenburg) they possessed large estates throughout Friuli.61 Their fortunes continued to improve with the notable inheritance of Tyrol in 1253.62 Their allegiance to the Habsburgs allowed them to gain control of Carinthia, Carniola and Istria, consolidating their control over the region. While there is significant evidence that the able Meinhard II aggressively struck at the lower nobility to consolidate his control of Tirol, there is no similar evidence that the Gorz took similar steps in Friuli.63 In fact this would have been unnecessary as the Gorz already had strong roots in Friuli and likely had lengthy complimentary relationships with the other Bavarian ruling families in the region. In fact while the Gorz were busy with problems from bishops, towns and monasteries they would have relied on their traditional powerbase in the region to "flex their muscles." 64 Unlike more distant overlords who had to be concerned with liberi becoming rebellious in their absence, the Gorz were close by. They had no need to work towards the extermination of the liberi, and there is no evidence that they did so.

After reaching this apogee under Meinhard II, the Gorz family suffered a series of setbacks. A number of political problems forced them to give up their original lands, and they eventually lost the possibility of claiming the kingdom of Bohemia between 1307 and 1310.65 Meinhard bequeathed extensive holdings in Carinthia to his brother Albert (who also received the original Gorz lands). The Albertine line of the family survived until the original family lands and their positions in Carinthia passed to the Habsburgs.66

The Meinhard line came to an end when Duke Henry (Meinhard II's son) died without male heir in 1335. At this time it appears that all of the lands in the Meinhard line's possession passed to the Habsburgs, including the titles of duke of Carinthia and Carnolia, and likely control over Friuli and Aquileia as well.67 Henry's heiress, Countess Margarat Maultash, was left with Tirol. Her marriages to the houses of Luxemberg and Wittelsbach were failures, and her only son predeceased her in 1363. She bequeathed Tirol to the Habsburgs, and they took possession in 1369. Thus the area where Fiore della Liberi was born passed into the control of the Habsburgs likely in 1335, and at the latest 1369.68

It is also important at this juncture to understand the nature of early Habsburg ambitions, or lack thereof, south of the Alps. While Rudolf I had the imperial title and power, his ambitions were very different from previous Holy Roman Emperors. He did not travel immediately to Italy to receive the crown from the Pope, nor did he embark on campaigns in northern Italy to secure traditional imperial holdings in this region. To those familiar with the usual conduct of the German emperors in this region, this is a clear and unequivocal break with the past.69 Rudolf and his son Albert I, focused their attention on the development, consolidation and expansion of their holdings north of the Alps. This was apparent to their contemporaries, including the noted champion of the Guelphs, Dante, who reproached both Rudolf I and Albert I for their greed keeping them north of the Alps and neglecting the "garden of the empire", Italy.70 The Habsburgs did not show significant ambition in Italy until the reign of Rudolf IV (1339-1365) and the Albertine line of the Habsburg family which followed.71

The significance of this information to our analysis lies in the fact that circumstances worked to ensure that Friuli and Aquilea remained somewhat of a backwater of the German empire and did not draw significant attention from the Habsburgs or other German princes until approximately the time Fiore was born. There is significant evidence of the Germanification of the region under the rule of the Gorzes and other Bavarian families who dominated the region for centuries, thus leading us to the conclusion that the "liberi" part of Fiore's title referred to that upper, though failing, milites class. Like so many other isolated locales, the march of social progress likely came late to the duchies of Friuli and Aquilia. When we combine the lengthy German history of the area and its isolated nature, it seems safe to conclude that fourteenth-century Friuli and Aquilea were among the regions where one could find the last living examples of liberi families.

The Habsburgs Turn South

The reign of Rudolf IV was to mark a significant departure in Habsburg policy south of the Alps. Rudolf is commonly known as "the founder" for his effectiveness in expanding and consolidating the vast Habsburg holdings over the period of his rule (1355-65). Most importantly for our analysis he was the first Habsburg to pursue an active policy of expansion and governance south of the Alps.72 He devised and carried out an effective "Italian policy" and greatly extended Habsburg authourity over Friuli and the bishopric of Trent.73 Rudolf IV's maneuverings allowed the family to inherit the majority of Istria, and the fruition of his Italian policy would result the acquisition of the city of Trieste in 1382.74 Austrian folklore aside, it was the actions of Rudolf IV that created a strong Habsburg presence in Italy that was to remain an important feature of European geopolitics until the end of World War I.

This Habsburg expansion and activity in Italy and its environs must have had an impact on the young Fiore and his family. It has often been said that for the farmer, artisan, and other toiling classes it makes no difference who held jurisdiction over a locality; the same cannot be said for the nobility of the area. The Habsburgs would have begun a campaign to ensure the loyalty and long term control of their newly acquired possessions, and this means appropriate taxation and structure of the local nobility. Despite the likely German origins of the liberi in Friuli, this was a bad development for their status and future. The common wisdom was that German holdings in Italy should be held by the more easily controlled ministeriale. The Habsburgs had over the generations shown a strong preference for relying on ministeriale, and a particular aggression and effectiveness in extinguishing the liberi. There is no reason to believe that the Habsburgs did not pursue a course to eliminate the liberi and import and develop their own ministeriale in the territories that had previously been held by the Gorz. Sometime shortly after the staged collapse of the Gorz-Tyrol family between 1335-1365, the family position of Fiore or his father Benedetto would have been under an unavoidable assault, designed to eliminate the remaining liberi or force them to give up their free status and become ministeriale.

The Origins of an "Austrian" National Identity

An analysis of when, how, and why the area known as Austria developed a national identity could fill many volumes on its own, and in fact it does. For the purposes of our analysis, a summary exploration will allow us to place the use of the word "Austria" in the Flos Duellatorum introductions into appropriate context. The most important feature of the birth of the idea of Austrian nationhood is that it was slow and tortured and took place at least one hundred years after Fiore's birth, and perhaps more than three centuries later.

From the time the Habsburgs obtained the imperial title the lands they ruled over were multi-ethnic in nature. Over the centuries the mixed ethnology and linguistic individuality of Habsburg subjects was to be both a strength and weakness for the empire, but it forced the Habsburgs to avoid a policy that associated their rule with a single ethnic, geographic or linguistic group. Thus with the Habsburg domains, more than any other major European power, the identity of the body politic was to be associated with the Habsburg family personally, rather than with the idea of a common nationalism or single ethnic mythology.75 So while France, Germany and England saw the use of nationalism and shared ethnology in support of various endeavors (civic, political and military) the Habsburgs, out of the necessity of ruling Germans, Slavs, Hungarians, Italians and other ethnic groups, consciously avoided associating their mechanism of state and governance with any one group or "nation."

The iconography and legal structure of the Habsburg Empire (which we often call by the convenient but inaccurate shorthand of the Austro-Hungarian Empire) remained fixed personally on the Habsburgs until at least the late 18th century, to good effect.76 The quintessential empress, Maria Theresa, considered now the Landesmutter of the Austrian nation and people, had to rely primarily on her claim to the Hungarian throne and the loyalty of her Hungarian subjects to allow the empire to survive her rule in the 1730s.77 The origins and legal foundation for this crisis can be located in the early Middle Ages, and reflects directly on the likely meaning of the word "Austria" found in the Fiore introductions. Ostrarrichi had been elevated to a duchy in 1156, but it never became a kingdom. So while at various times the head of the Habsburg family held the imperial title (or some version of it) they gained their royal privilege in the later Middle Ages, through the Renaissance and into the modern era, due to the fact that they held the crown of the kingdom of Hungary (and at times that of Bohemia). For all of the period that we are concerned with "Austria" was only a duchy in the Habsburg holdings, amongst other valuable duchies such as Styria, Carnolia, Carinthia, Tyrol, etc.

It is interesting to note that Aquilea became a duchy in 1180 and the Patriarch had exercised the powers of ducatus for some years before this.78 Thus, from a legal or dynastic perspective in the period we are concerned with Austria and Aquilea would have been held in virtually equal regard. The key point for our analysis is that there would be no reason for someone from the Aquilia/Friuli/Cividale region to refer to themselves as Austrian, unless they were actually from the geographic area known as Austria. Imperial influence in the region would have been called just that, or perhaps Habsburg influence. The very earliest argument that might be made for something equating to an Austrian national identity (and this would only be supported by the most fervent Austrian nationalists) would be around 1478, long after Fiore had passed away.79

What's in a Name?

Despite the metropolitan nature of the world today, we operate under the assumption that we can learn something of an individual's familial history via a surname such as Jones, Pantani, Ulrich, Jalabert or Takahashi. Similar assumptions could be taken from first names such as Johann, Francois, Vito, or Hassan. However, this kind of rudimentary analysis cannot offer us any assistance in our search for answers about Fiore.

In the Italy of the time Fior Di Battaglia was penned, the tradition was to Italianize the names of individuals being discussed to a degree that made it impossible to discern anything of the origins of the person so named. Similarly, in North America we tend to anglicize names so that when we see someone referred to as Peter, we don't learn much, since he may well have borne the name Pietro, Pietr, Petrovich, and so on. The examples we find within the introductions to Fiore's work are instructive. To the modern (and probably the medieval) mind merely hearing or reading the name on the left would not lead one naturally to the nationality listed on the right:

Piero del Verde – A German

Piero de la Corona - A German

Nicolo Voricilino - A German

Nicolo Inghileso - probably English

Sir Bucichardo - A Frenchman

Sir Baldassaro - A German

Perhaps this is why Fiore in many cases would very directly name the ethnic origin of the subject, because it would not be readily apparent to the reader but was important. The most famous foreigner in Italy in the era was "Givovanni Acuto", a name which would offer little clue to the gentleman's English origins and his better-known name, Sir John Hawkwood.80

We are also faced with the possibility that Fiore was not the real name of the author of these texts. Fiore may well have been his nom de plume, or perhaps more suitably, nom de guerre. Many medieval manuscripts are written by authors whose names are either fabricated for the purpose of the work, or were descriptive nicknames for the individual. Even some of the most important Arthurian tales were penned by individuals who likely did not use their own names. Some suggest that Fiore della Liberi could easily translate into "the cream of [the best of] the free knights". However a careful look at the construction of the prologue in the original languages seems to eliminate this possibility, for we can say with some certainty that we are dealing with Fiore from Friuli who was from a noble family of Liberi. In addition, this name was not uncommon in the Italy of the period we are concerned with and had significant religious meaning at the time. Joachim dei Fiore was an important Italian monk who had been beatified in the centuries before, and in some places St. Mary the Blessed Virgin was referred to as St. Mary dei Fiore.81 There are also references to a Saint Fiore; however, my sources have not revealed useful information about this saint.

Analyzing the Competing Theories

- Fiore was Italian

Two of the strongest arguments advanced to support the theory of Fiore's Italian ethnicity are Fiore's name and the fact that his texts were written (for the most part) in Italian. While the name may provide some guidance, considering the modification of names both within the manuscript and in the period in general, it is not a certain guidepost to Fiore's ethnicity. We can see from the analysis of names above that names in the manuscript were clearly Italianized and that this was a common practice in the period. It is possible that Fiore is a modified version of a non-Italian name.

On initial review the fact that the manuscripts are composed in Italian would seem to be very strong evidence that Fiore's origins were Italian. However, upon closer examination, there are problems here as well. The quality of the Italian seems to be poor at best. One of the most respected authors in the field, Dr. Sydney Anglo, refers to the quality of the writing in the Getty manuscript (likely the oldest of the extant copies) in the following fashion: "the Getty manuscript has much longer descriptions set in verse so bad as to be barely recognizable as such." 82 There are other native Italian speakers who have examined the Getty and other Fiore manuscripts that have commented on the poor quality of the Italian to be found there.83 Thus, based on the weakness of the Italian found in the manuscripts (particularly the Getty) it seems feasible to suggest that Italian was not Fiore's native language; rather it may have been his second or later language. Some caution must be expressed in this regard though, since due to the geographical location of Fiore's home and the region's longstanding German influence the dialect of the area may have been quite different from what we might expect. Unfortunately, we do have any samples of Fiore writing in another language to compare it to. We can nonetheless conclude that the quality of the Italian found in the manuscripts casts doubt on the "Fiore was Italian" theory.

There are other problems with the Italian conjecture. No section of any of his manuscripts deals with fighting with the shield, while the Italian style of the period involved heavy armour and the shield.84 If this were such a common fighting style among Italians of the period, why is there not instruction on it in the texts? One also has to question why nobles in an area that had been dominated for centuries by German princes and their appointees would be Italian. It would seem more likely that the German rulers would have ensured that the local nobility were made up of their relatives and allies, other Germans. We must also consider that the condotteri who came from this region had a unique fighting style that was described as "German" in nature.85 Thus there are significant reasons to doubt the contention that Fiore was Italian in background.

- Fiore was Austrian

This particularly pernicious theory that Fiore was Austrian finds its roots in the prologue to the manuscripts wherein the master is being referred to as coming from "civida d'Austria". Two distinct hypotheses have evolved around this reference, both of which are inaccurate due to their anachronistic importation of modern concepts. The first hypothesis claims that Fiore was indeed an Austrian. The second hypothesis asserts that due to long or intense Austrian control or influence in this region this term was used to reflect the Austrian character of the region. Upon careful analysis, both of these ideas are found to be inaccurate.

Other than the use of the word "Austria" in the prologue there is absolutely no evidence to support the contention that Fiore was Austrian. As we have seen, the concept of Austria was very limited in this time period and was not used to describe the extra-territorial ambitions of the Habsburgs. There is simply no evidence that Fiore had come from or had been to Austria. Even Habsburg influence in the region was not significant until the reign of Rudolph the Founder and the fall of the Tyrol-Gorz between 1335-1369. Thus Habsburg control of the area was just beginning at the time when Fiore was born.

The second hypothesis is also not supported by the evidence. The influence in the region was not "Austrian" at all (Austria being a very specific region at the time); rather it would be referred to as Habsburg or imperial influence. Even if by 1409 a man born in this region now governed by the Habsburgs (when his father surely would have been born under the Gorz rule) might begin to refer to his home region as part of the Habsburg holdings (which is doubtful in and of itself), he simply would not have referred to the area as "Austrian". Fiore's clear listing of Niccolo III's holdings tells us that Fiore was more than capable of understanding how to express territorial control accurately, and he clearly personalizes the rule (as was the custom of the time) to Niccolo, not the "Ferraranese" or some other equivalent of "Austrian." This leaves us with the question of what the reference to Austria means in the Fiore prologue.

While history is not a science, it sometimes helps to apply Occam's razor to a problem to reach an elegant solution. The city currently known as Cividale was known since the eighth century as ‘Civitas Austriae,' and was the seat of the Patriarch of Aquileia, a position it retained until 1031.86 Thus the area where Fiore was born already had the moniker "Austriae" attached at least 180 years before the area now known as Austria was referred to as "Ostarrichi" (around 970). Civitas Austriae simply means city or community of the South. Therefore, it appears that there is no evidence that connects Fiore de Liberi with Austria proper, and the reference in the manuscripts to "civida d'Austria" refers to a rather ancient name for modern Cividale del Friuli.

- Fiore was Dalmatian or Slovenian

While one might be compelled to reject out of hand the contention that Fiore was Dalmatian or Slovenian, there is substantial geographical and historical evidence that compels us to consider the possibility. Examination of a map of the region shows the proximity of these peoples to the area we are concerned with. There was significant trade and migration between the Dalmatian and Slovenian peoples with this isolated corner of Italy (or perhaps more properly "of the empire") stretching back centuries. Many of the communities along the coast of the Adriatic had significant populations of Dalmatians and Slovenians who developed some peculiar dialects of Italian over the years, in fact, a localized mixture of Italian and Slovenian is spoken in Premariacco today. This may be one way of accounting for the challenging Italian and poor verse found in the Getty manuscript. It is also a possible explanation for the fact that no specific Italian noble family name from the places named in the manuscript has been connected with Fiore. Based on our knowledge of the region in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries it remains a possibility that Fiore was a Dalmatian or Slovenian.

However we must approach this theory with caution as there is very little, if any, evidence to make a positive connection between either of these groups and the master. There is no specific historical evidence that associates large communities of these peoples with Friuli or even specific examples of historically important people of these ethnicities playing a role in the region. There is also no information about any sword masters from these regions traveling to Italy to ply their trade or participate in the maelstrom of conflict that was Italy in this period. While it remains possible that Fiore was a Dalmatian or Slovenian, it certainly does not approach the level of probable. While it is not yet possible to completely rule out these theories, for the time being it seems we are safe in assigning them to the category of remote possibilities. Of the possibilities that we have examined thus far it would seen that the Austrian fallacy can be discarded entirely, Dalmatia/Slovenia can be relegated to the "unlikely" pile, while the obvious answer of Italian heritage is the strongest possibility, but cannot be elevated to the level of probability.

- Fiore was German

There is a great deal of evidence that Fiore della Liberi was of German extraction. As we have reviewed above, there was a centuries-old connection between various German states (particularly Bavaria and Tyrol) and the governance of Friuli. Over such a lengthy period of time it is likely that many of the local nobility would have been German allies and relatives of the Kings of Bavaria and Dukes of Tyrol. No other part of Italy remained under such continuous and complete German rule as did Friuli. The Patriarch of Aquileia was almost always appointed by a German prince. Perhaps most importantly, the class of liberi was a particularly German animal. It seems difficult to imagine, considering the descriptive nature of medieval names, the construction and placement of the term in the manuscripts, and the fact that Liberi does not seem to have been an Italian surname, that master Fiore was not a member of the class of liberi milites.87 Thus evidence supports the conclusion that, even if Fiore was not German by descent, his family's title was German in origin and nature. Effectively, while this would have offered his family a great deal of status in the region, it means that he would not have formed part of the Italian nobility proper.

The German theory would account for a number of the facts we know about Fiore's background from the manuscripts. If German were the language of the household, it would explain the weak Italian verse found in the Getty manuscript. A fluency in German and having German relatives and relationships would account for the large proportion of Germans we find amongst his students. We must also integrate the fact that while Fiore mentions that he trained with both Italian and German sword masters, the masters he actually specified are German, while none of the Italian masters are named. This can be explained in at least two ways: first, that Fiore only trained with German masters but added in the vague reference to Italian instructors in consideration of the fact that his audience would be mostly Italian, or second, that he trained with both Italian and German masters but only felt that the German masters were worthy of mention by name. Either explanation would support the contention that Fiore was of German extraction.

Clues contained in the fighting style described within Fiore's work and that used in Friuli in general support this contention. The fighting style of Italian troops in this period involved the use of heavy armour and very often the shield. Fiore's manuscripts, while certainly being broad in purview (armoured, unarmoured, mounted, on foot, unarmed, armed with various weapons), offer nothing about fighting with a shield. While this was a dominant feature of the Italian infantryman during this period, we see no instructions on its use. It is therefore possible that Fiore was not an Italian raised to fight in the Italian style, but rather a man of German descent, trained to fight in the German style.

Since we are confident that Fiore's roots are found in the Friuli region, perhaps something can be gleaned from what is known about the military style of that region in the relevant period. Noted medieval military historian Dr. David Nicolle described the troops that came from the Friuli region in the condottieri period as follows:

"During this same period horseman came from Friuli in the far northeast of Italy; an area where Germanic military fashions appear to have been particularly strong." 88 This is a strong statement that forms a key piece of the puzzle of understanding the origins of Fiore della Liberi. It is not surprising, considering the centuries-long German domination of this region, that the "fashion" of fighting was German in character. But where Dr. Nicholle states the simple fact, to focus more clearly on this piece of evidence we must go a step further and ask why.

In the medieval period, particularly in Italy in the timeframe we are concerned with, the style of warfare was dictated by money. Making war was an expensive proposition, either for the individual arming himself or for the political organization fielding armies for a campaign. Military fashion was dictated by the ruling classes, of whom we can confidently say Fiore was part.89 Thus we are drawn inexorably to the conclusion that the military ruling class in Friuli in the condottieri period was German. They likely remained in close contact with their friends, allies, associates and most importantly their liege lords in Bavaria, Tyrol and Austria. Thus the military style adopted in Germany was adopted in Friuli, not just in imitation but because the nobility of Friuli felt that they were German. This was the social class that produced master Fiore.

Thus it seems that the preponderance of evidence points to the conclusion that Fiore was of German extraction. While this theory seems the strongest available to us, we cannot say conclusively that it is correct, or even "probable," though it is by far the most likely of the options available.

- Fiore was a Graduate of the University of Vienna

It is sometimes claimed that Fiore graduated (or attended) the University of Vienna. Duke Rudolf (the Founder) founded the University of Vienna in the last year of his life, 1365.90 Thus, if we are working with a birth date of around 1350 for Fiore, the University would have been functioning in his early adulthood, when he may have chosen to attend. Some have suggested that that since Fiore likely spoke three languages and had some artistic talent it implies a higher level of education that would have been available to a liberi in Friuli. It is also hard to deny that that fighting system espoused by Fiore could be constructed and integrated with anything short of significant intellectual rigour. The system is highly logical and sophisticated and is brilliantly woven together into a nearly sublime whole. No matter what formal education can (or will) be attributed to Fiore, his works on combat are genius.

This claim, of all the theories, is perhaps the hardest to come to draw conclusions about. There is no doubt that Fiore was widely-traveled and would have been able to travel to Vienna to study. He makes no mention of any such studies in his manuscripts, but what value would they have added to his audience? Perhaps the largest stumbling blocks to this theory arise in the realms of motivation and timing. It is hard to imagine what Fiore's motivation for attending such an institution would be since he was clearly set on studying the martial arts since a young age. In addition, when we look at the potential length of his studies, consider travel times, the number of duels he fought and trained others for, and assume that the Fiore that fought at Udine is the Fiore we are concerned with, it is hard to discern just when he would have attended Vienna to study. There certainly is flexibility in the Fiore chronology, but probably not enough to allow for a lengthy stay in Vienna.91 While there is little we can say with certainty about Fiore's activities between 1390 and 1408 or so, it seems unreasonable to speculate that he would have taken time to study considering that he had already established his martial vocation.

However the University of Vienna reference does give us some further insight into the contemporary concept of Austria, which further refutes the thesis that Fiore was Austrian. The University of Vienna's student body was divided into "nations" based on the student's land of origin. One of the nations was the "Austrian Nation." 92 Ironically enough, this first recorded use of the term did not refer to any unified ethnicity or connection to the geographical location of the same name. Rather the "Austrian Nation" referred to all of the students who came from the Austrian lands proper but also from Aquileia, Italy and all other territories South of the Alps (which would include parts of Slovenia, Dalmatia, Sicily etc).93 So in some contemporary lexicons anyone from Aquileia or even Italy could be referred to as "Austrian". This is another strong indicator that the term Austria as it appears in Fiore's manuscripts offers no guidance as to his ethnic or cultural origins.

More of the Name Game

One of the objections to the German thesis is that the name Fiore della Liberi does not sound in any way German, and if the author were German he would have used his name accurately in writing the manuscript. Upon close examination this objection loses a great deal of its force. We have already noted above that the term Liberi has a direct connection with a certain class of German knights, so we will limit our inquiry here to the name Fiore.

Directly translated from Italian, Fiore means "flower". It is a name not unheard of in Italy today, or in the medieval period, though usually as the second or descriptive name, not the first or personal name. Names were much more flexible in this period than they are today. We must keep in mind that in the period we are concerned with second names were descriptive and were not yet inherited as part of one's legal name.

There are at least two explanations for appearance of the name Fiore being used by a German in Friuli in this time period. The first concerns changes in German naming patterns that were occurring around the time we believe Fiore was born. Around 1350, there was a great shrinking in the world of German names, replacing traditional names with the names of international saints and religious figures.94 From thousands of older German personal names, the range shrank (over a period of a century or so) to about 400.95 It is entirely possible a German noble in this period would name his son Fiore, after perhaps the monastic mystic prophet Joachim Fiore, or perhaps Fiore's family was fond of Mary, who was also known in some regions as Saint Mary de Fiore.

The other possibilities relating to the name Fiore being used to identify someone of a German origin consists of the Italianization of a German name (as discussed above) or the name having a symbolic meaning, rather than a literal one. The Italianization of a German name could have happened in two ways. The first method would be the bastardization of a name phonetically, transforming a German name into a similar-sounding Italian name. There are a number of examples of this in period literature. It is also possible (and perhaps more likely) that Fiore's German name could have had a meaning relating to a flower (or a type of flower) and was translated to the Italian Fiore on this basis. Names based on variations for the German word for flower, Blume or Blumen, are well known from the period, and some of them were associated with families of the social class that we believe that Fiore originated from.96

Lastly, the name Fiore could have been based on a visual image associated with the maestro's family. It is possible that his family heraldry featured flowers. Since a knight's identity was intimately associated with his coat of arms, it is not a leap to posit that such a symbol provided the basis for an individual's nickname or nom de guerre. There are certainly many examples of the use of flowers in German heraldry of the period.

Why Fiore Left Friuli

Based on the analysis above it seems most likely that Fiore was from a German family that was based in the Friuli region for a number of generations, perhaps more than a century. Much of the historical, political, social and linguistic evidence we have points to this conclusion. A number of the biographical details of Fiore's life found in the prologues of his manuscripts also support this proposition. Where the biographical, linguistic or historical data does not support this conclusion, it certainly allows for it.

The historical data also offers a plausible explanation as to why he left the estates of his liberi family for the life of a traveling sword master or soldier for hire. The Habsburg family gained control of the region either shortly before Fiore's birth or while he was a young man. The Habsburgs were often ruthless in the elimination of liberi lineages, replacing them with ministeriale or forcing the liberi into that unfree status. As time passed and the Habsburg hold tightened, the future (or even the present) for Fiore's family status and privileges would have been grim indeed. If Fiore was to maintain his liberi status for himself, his family and his potential heirs, he would have to seek his success in places other than Habsburg-controlled Friuli. While this may explain young Fiore's choice to leave his home region, it leaves a compelling question unanswered. Why Ferrara?

Ferrara in the Time of Fiore

While it is unclear just how strong the connection between Fiore and the city of Ferrara was, his seminal work was dedicated to the Marquis Niccolo III d'Este, who was the young ruler of Ferrara at the time the Fior di Battaglia was written in 1409. Ferrara itself was a second-tier power in this era, and Nicolo would pursue a policy of peace after the early part of his reign, recognizing his inability to succeed in direct conflict against the greater Italian powers of the day. 97 The Este had first shown an interest in Ferrara in 1180 and were not from the city; rather their ancestral lands were located south of Padua and around the castle of Este.98 The story of the rise of the Este to power against the interventions of the papacy, other cities, and internal tensions is a fascinating one but largely beyond the scope of this work. By way of summary, the Este began exerting influence in Ferrara when a branch of the family moved there to take control of lands they inherited from deceased followers. Technical transfer of arbitrary power to the Este took place in 1264.99 Early in the fourteenth century the Este went to war with the papacy and lost control of Ferrara. Only fine diplomacy allowed the family to regain control of the city from the church, through the granting of a papal vicarate for a period of ten years with significant "rent" to be paid. This was later extended to rule for life, and over time the Este began ignoring their financial obligations to the papacy, with few negative consequences.100

Socially and economically, Ferrara was an eccentric city. While much medieval history testifies to the modernization of social and economic institutions in Italy in advance of other European nations, the late medieval period saw a reversal of this trend in Italy. This ‘re-feudalization' meant the shift of capital from trade to land, the advance of aristocratic feudal values, and the undoing of many achievements in social and economic growth. While almost all of Italy went through this process Ferrara was well ahead of the curve in this regard.101 This may be partially explained by another eccentricity of Ferrara, the failure of the city to develop strong guilds or powerful commercial interests.102 Thus when Fiore reached the city, in 1400 or later, the system of political and social control was firmly feudal in nature.

There are at least two other features of the Este rule that may well have contributed to Fiore's choice to seek to advance himself there. The first is that in contrast to other cities in Italy both fiefs and grants of land were used to reward retainers.103 This was uncommon in the 1330s but by the 1390s and into the early fifteenth century this had become very common in Ferrara. Many of these gifts of land were quite small, such as a single house in the city of Ferrara itself, partially due to a shortage of cash due to a series of setbacks the Este suffered through Niccolo's regency (which ended in 1402) and the early years of his reign.104 There was a clear predominance of "ignoble" fiefs granted during his early reign, and more than two-thirds of the fiefs granted were between one-half and twenty hectares.105 The recipients were also notable, almost all of them were granted to foreign nobles who did not originate in Ferrara.106

The fiefs were granted to individuals from many social classes and occupations.107 Many small fiefs were granted to minor officials and household staff, including families of modest origins. Up to 1410 or so a large part of the fiefs granted went to military servants, being used to reward but not remunerate military service.108 The largest grants went to military captains, but what is new about the Este vassals in the regency period of the 1390s was the large number of foreigners not present a century earlier. One theory behind the numbers of grants of land to condottieri was that the Este were trying to create permanent loyalty amongst the notoriously fickle mercenaries. This is why the fief was used as the chief instrument of land grant. As one preeminent historian of late medieval Ferrara noted, "the service of outsiders and reward in fief went together." 109

Marquess

Niccolo III d'Este

So who was the ruler that Fiore dedicated his works to? Niccolo III (1383-1441) was the legitimized natural son of Alberto d'Este, who ruled Ferrara from 1388-1393.110 The late fourteenth century and early fifteenth century was a challenging time for both the city and the Este. The period saw floods, famine, at least one outbreak of the plague, and significant political unrest.111 The period of the regency saw a number of small wars which cost the Este control over significant territory.

In 1397 Niccolo, then thirteen, married the daughter of Francesco Novello da Carrara, lord of Padua. Immediately after the wedding Francesco seized the city, executed the direct regent, disbanded the counsel, and stationed Paduan troops throughout Ferrara.112 A protectorate was established over Niccolo's state, and the young prince was a mere puppet. By 1402 Niccolo had fended off the Paduans by threatening the Venetians with a Milanese alliance and established his personal control over Ferrara.113 The early part of Niccolo's reign saw a number of campaigns where he proved himself as a military leader, including one particularly significant invasion by the armies of Venice that commenced in 1405.114

The most threatening military period of Niccolo's reign came to an end in 1409 with the assassination of Ottbuono Terzi at a "peace-meeting" near Rubiera in 1409.115 After this period Niccolo succeeded primarily through diplomacy and not war. He carefully built alliances and played off the greater powers one against the other to preserve and expand Ferranese influence. As the years went on his reputation as a peacemaker grew, and he brokered a number of significant peace agreements and hosted many diplomatic missions and conferences. Despite his success as a statesman, Niccolo never achieved financial success, and he suffered from shortages of money throughout his reign.116 Niccolo died in 1441 while enjoying another diplomatic success. He was summoned to Milan by the ailing duke in the aftermath of a Milanese-Venetian truce he had helped broker. The duke, having great respect for Niccolo, appointed him to serve as governor of the Milense state. Within a month of his appointment Niccolo died suddenly at age 58. He was likely poisoned by the duke's son-in-law who feared his claim to the duchy might be lost, although he may well have had the backing of the Venetians or the Florentines who feared the expansion of Este influence over the entire northern part of Italy.117

Niccolo the Man

While understanding his political and military machinations tells us something about the individual, there is a value in having a closer look at this northern Italian prince to understand the man that Fiore was dedicating his book to. Niccolo was described by Pope Pius II as "fat, jocund and given up to pleasure" and has been likened by some historians to King Henry VIII of England.118 He certainly seems to fit our stereotype of the signore of the age being capricious, strong-willed, and quick to anger while still being generous and open to counsel.

In his public life at least, Niccolo evidenced a strong and demanding religiosity.119 However, on balance, the record of his deeds reveals a contrast of public faith and private transgression that is remarkable even for this era in Italy. In 1413 Niccolo undertook a lengthy pilgrimage to Jerusalem where he visited a number of holy sites. This entire trip took three months, and speaks to the apparent stability in Ferrara, both internally and externally, at the time such that the ruler could leave his home for such an extended period of time.120 In later years Niccolo undertook pilgrimages to many other places and seems to have enjoyed the process. There was clearly something about the idea of a religious mission combined with the pleasures of a grand tour that appealed to the marquis.121

Niccolo did not fail to attend to his religious obligations at home. In February 1414 he entertained Pope John XXIII for a week before the leaving on yet another pilgrimage to Spain that ended in Piedmont. Later Martin V visited Ferrara and slowly the city became a favourite of the papacy both for its peace and stability and its prince's very public affirmations of faith. Most important was the hosting of the Council of Ferrara-Florence in 1438.122

However Niccolo's personal life stood in stark contrast to his public religiosity. His sexual proclivities would make a modern Hollywood libertine blush. While he had three wives, the vast majority of his children were borne by other women. By the time of the passing of his first wife in 1416, he had three sons from his favourite mistress that he treated as legitimate.123 Although we are unsure of how many children Niccolo had, a conservative number would be around 35.124 One chronicler suggests that Niccolo had 800 lovers and had a certain appeal to foreign ladies he met on his pilgrimages.125 Despite the fact that Ferrarese law made adultery a very serious crime, Niccolo was always known as a great respecter of the law in both form and content.

When angered, Niccolo's rage and thirst for vengeance appeared to know no bounds. In 1425, Niccolo discovered that his oldest and favourite son, Ugo, was engaged in a carnal affair with Niccolo's second wife, Parisina. Despite pleas for clemency from his most respected advisors he ordered the beheading of both his son and wife, but nonetheless followed the prescribed legal forms. After the executions, copies of the official sentence were sent to Ferrara's allies in an attempt to justify an act which appeared "practically unintelligible in the light of Niccolo's own sexual proclivities." 126

During Niccolo's later reign (from 1431 onwards) he became an avid collector of books in all disciplines. This would eventually provide the basis for La Biblioteca Estense.127 While we know nothing of Niccolo's own literary tastes (he does not seem to have been an avid reader) this development likely took place due to the influence of the notable humanist scholars he had engaged to tutor his sons. A great deal of effort and money went into the building of this collection with books being sought after from many sources.128 However there is no evidence that Niccolo had shown the slightest interest in collecting or commissioning books in the period in which Fiore wrote his work.

Why did Fiore go to Ferrara?