A Brief Examination of Fiore dei Liberi's Treatises

Flos Duellatorum & Fior di Battaglia

Journal of Western Martial Art

September 2008

by David M. Cvet

SynopsisFiore dei Liberi's legacy created 600 years ago is honoured in the 21st century with the careful reconstruction and resurrection of the fighting art he described in his treatises entitled “Flos Duellatorum” and “Fior Battaglia”. This paper will explore the man who bore the name Fiore and conduct a brief comparative analysis of the three versions of the treatise. It is evident in the Western fighting arts community, that the treatises are considered as important cornerstones in todays research and reconstruction of historical Western fighting arts. The reasons are numerous, but perhaps their greatest value is their collection of illustrations possessing remarkable clarity in conveying the concepts in the art, and the imformative text accompanying each illustration, together creating a recipe for a comprehensive resource supporting today's research, practice and reconstruction of historical Western fighting arts.

The Man

Despite the significant impact Fiore's treatise has had on the modern reconstruction of historical fighting arts, in particular, armizare1, very little is known of the man who bore the name Fiore dei Liberi. To date, given the extensive and ongoing research being conducted world-wide by a variety of historical fencing schools and academies2 the only definitive source for Fiore's biography has been the prologue written by Fiore himself contained in each of the three versions of the treatise3.

The treatise, authored by Fiore himself, styles himself as “Fior Furlan de Ciuida dostria “ in the Getty's prologue, “Fiore Furlan de Ciuida dostria ” in the Morgan's version and “Fior furlano dei liberi de Ciuidal dostria ” in the “alter prologus ” in the Pisani-Dossi (PD) version. The PD phrase translates into “Fiore Friuli of the family of the Liberi from Cividale d'Austria4” which is commonly abbreviated to “Fiore dei Liberi”. The prologue tells us that Cividale d'Austria was part of the Diocese of Aquileia5 and that he was born the son of “meser benedetto de la casada dei liberi da premergiago6 ” translated as “Sir Benedetto of the House of the Liberi from Premariacco”. The village of Premariacco and Cividale d'Austria (now Cividale del Friuli) both exists today and reside in an area known as “Friuli7”, an area with its own unique cultural and historical identity. Cividale del Friuli is the last known residence of Fiore based on the extracts from the prologues.

Fiore does not reveal his birth date nor year in any version of the treatise, however, it is estimated that Fiore was born sometime around 1350. This estimated year becomes more apparent upon further examination of the text extracted from the prologue. He wrote that he had possessed a natural combative ability at a young age, having left his village of Premariacco to learn more advanced fencing techniques and to increase his skills by traveling to many provinces, training under many Italian and German masters. He stated that he had been training and fighting for more than 40 years8, and given the timing when he started writing the treatise on 10 February, 1409 and the assumption that he started training and fencing at the age of 10 years, would make Fiore somewhere around sixty years of age at the time of writing the treatise.

Fiore wrote that he trained under different masters in different provinces at great personal expense, implying that he was able to draw upon family resources indicating some level of financial stamina in the least, indicative of a modest noble family. He indicated that he trained under many Masters and Scholars, as well as trained in the courts of great gentlemen, Princes, Dukes, Marquises, Counts, Knights and Squires. He mentioned by name only one of the masters he studied under and only in the Pisani-Dossi version, “Et maxime a magistro Johane dicto suueno qui fuit scholaris magistri Nicholai de toblem mexinensis diocesis ” translated as “and above all , namely Master Johane Suueno9, who was a scholar of Master Nicholai of Toblem of the Diocese Mexinensis10”. Unfortunately, there are no further details on these two gentlemen in Fiore's treatise and therefore, no further illumination on their biographies can be extracted from the prologue.

Interestingly, Fiore doesn't elaborate on the decades of his own military service, duels and swordsmanship instruction given and/or received in the prologue. However, Zanutto11 revealed that Fiore may have been in service of Udine during the civil war which broke out in 1383 following or more accurately, provoked by the ascension of Filippo d'Alençon to the Patriarchate of Aquileia two years earlier in 1381, where Fiore is recorded12 as being in charge of the crossbow-men and artillery or ballista, as well as procuring arms & gunpowder for the defense of the towns in the alliance with Udine. Details of the civil war are few, however, Udine did prevail, and the village of Premariacco, in fact, a few villages and towns who were in the alliance who honoured Fiore's part in the war by naming a street after him – Via Fiore dei Liberi. Other archived documents suggest that Fiore was also in Padua in 1395 and Pavia in 1399, but further detailed examination of these instances is beyond the scope of this paper.

What Fiore did write and only in the Getty and Morgan prologues, were brief accounts describing feats of arms of some of his students13 who fought in the barriers, such as Sir Piero del Verde14 who faced Sir Piero de la Corona15, both German16 who fought in Perosa. Another of his students, Sir Galeazzo from Mantoa17 described as a “valiant and strong knight” fought with the French knight Boucicault18 in the field at Padua in 1395 which was more akin to a duel of honour, provoked by Boucicault's allegation that Italians were cowards.19 He wrote of a Sir Nicolo Voriçilino20, a German who fought with Nicolo Inghileso21 ("one who is English") at the field at Imola. Another account of the valiant squire Lancilotto Beccaria22 of Pavia who faced Sir Baldassaro23 a German. Baldassaro, both on horseback, received six thrusts from Lanzilotto's lance. They continued to fight in the barriers, all occuring in Imola.

24 who faced a valiant German squire by the name of Sram set in the field at a castle in Pavia. They duelled with a count of three thrusts of a lance of "soft iron25" on horseback. Fiore continued to elaborate the duel which then continued on foot to the count of three blows of axe, three blows of sword and three blows of dagger, all in the presence of "countless" high ranking nobles including the prince and the Lord and the Lady Duchess of Milan. Details of the outcome of this duel were not revealed in the prologue, however, it would be doubtful that Fiore would write on a student who wasn't victorious.Other duels involving his students mentioned in the prologue include Sir Açço da Castell Barcho26 who fought with Çuanne di Ordelaffi27, and the valiant and good knight Sir Jacomo di Boson28, although no details on whom Jacomo faced in the duel. No other details describing the duels were included in the prologue of either version nor any external references describing these duels have been found to date.

In the Pisani-Dossi prologue, in the "alter prologus " section of the prologue, the phrase "...che io predito fior o uecudo mille chiamati magistri che non sono de tuti loro quatro boni scholari e de quilli quatro boni scholari non seria uno bon magistro. " is written in which Fiore almost "boasts" having seen thousands of self-styled masters of which only four were considered good Scholars by Fiore, and of the four good Scholars, only one would be considered a master in Fiore terms. This claim is not included in the Getty nor the Morgan prologue. However, in the Getty and Morgan prologues, it is mentioned that Fiore was challenged to five duels, using cut and thrust weapons, wearing only an arming doublet29 and leather gauntlets ("chamois") because he did not wish to fight nor practice the Masters who challenged him. These duels occuured in locations without any supportive relations and friends, but apparently, his honour was and remained secured.

Without a doubt, the most vexing part of Fiore's life were his later years, at the end of the 14th century and the beginning of the 15th century during the period of time of the composition of his treatise or treatises. The “alter prologus ” in the Pisani-Dossi version highlights Nicolo III d'Este and Marquis of Ferrare30 and mentions that the composition of the treatise including both the writing and the illustrations were at the request of Nicolo. This implies that Nicolo was Fiore's Patron and therefore commissioned Fiore to compose a book on combat to satisfy Nicolo's desire to add to his extensive bibliographic collection. There is nothing in the prologue which may indicate that Fiore was a member of the Marquis's court and given Fiore was a reputable and notable swordsman, Nicolo's library was enhanced with the addition of Fiore's treatise which he started writing on February 10, 1409 and completed the treatise some six months later.

Interestingly, there is no mention of the Marquis de Ferrera in the Morgan's prologue, in fact, there is no mention of anyone who may be interepreted as being Fiore's Patron. Fiore writes of his students and their feats of arms, with an obvious omission of Nicolo III from the list of his students. By the time Fiore began his composition of “Flos Duellatorum” (Pisani-Dossi version), Nicolo would'be been 21 years of age and therefore, would've had plenty of time to receive instruction and test his skills in the barriers.

However, we find Nicolo d'Este Marquis de Ferrera, etc. mentioned in the Getty's prologue. In fact, it appears that the Marquis has provided instructions to Fiore on how to structure the treatise in order to serve Nicolo's needs or desire. This raises the question about whether Nicolo was Fiore's Patron, or perhaps he was one of Fiore's students, and wielded enough power and resources to request a copy of the art for his own reference to armizare? Perhaps Nicolo had the desire to become or at least be perceived as a master, given that Fiore states in the prologue that no man has a great enough memory to remember the complete art without the aid of such a book. Yet, Fiore's prologue has no mention of Nicolo as one of his students demonstrating feats of arms of the knowledge and skills learned from Fiore.

Unfortunately, the prologues obviously do not include the year of Fiore's death, and to date, there are no records, archived or otherwise which reveal Fiore's activities after 1410. Presumably, he died sometime between 1410 and 1420.

The Treatises – A Brief Comparative Analysis

There are presently four known versions of of Fiore's treatises on armizare. The following are some specifics which will aid in the ensuing discussion. The exact citations are:

- Fior di Battaglia: MS M.383 - The Pierpoint Morgan Library (codice "MORGAN")

- Fior di Battaglia: MS Ludwig XV 13 - J. Paul Getty Museum (codice "GETTY")

- Flos Duellatorum (Pisani-Dossi MS): F. Novati, Flos duellatorum: Il Fior di battaglia di maestro Fiore dei Liberi da Premariacco (Bergamo, 1902)

- Florius de arte luctandi: MSS LATIN 11269, Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF)

The provenance for the Morgan version is:31

- MS M.383 is the lost codex MCCLXI of the Biblioteca Soranzo in Venice (Library of Jacopo Soranzo, Venetian senator, 18th century) sold in 1780;

- Matteo Luigi Canonici (1727-1805); his sale London Sotheby's, June 15, 1836, no.40) to -

- Rev. Walter Sneyd of Bagington Rectory, Coventry; his sale (London, Sotheby's Dec. 19, 1903, no. 720) to -

- Ellis; Tammaro de Marinis, catalogue 8, 1908, plate 9);

- purchased by John Pierpont Morgan (1837-1913) from T. de Marinis in 1909;

- J.P.Morgan (1867 - 1937)

The currently understood and generally accepted provenance for the Getty version is:32

- Niccolò Marcello di Santa Marina Venezia

- Apostolo Zeno (1668-1750)

- Luigi Celotti (1789 ca.-1846 ca.) - vendita da Sotheby nel 1825

- Thomas Phillipps - numero indicativo Ms.4204 - vendita da Sotheby nel 1966

- Peter e Irene Ludwig di Aachen (Aquisgrana) - Germania - dai quali prende il nome.

The Pisani-Dossi version, the most popular and widely accessible version on the Internet for more than ten years, has a prologue composed of two portions, the first in Latin, and the second more comprehensive portion “alter prologus ” in Venetian dialect of Italian. Its prologue is quite unlike the other two versions, in that it completely devoid of any description of the feats of arms of Fiore's students, and mentions Fiore's career as 50 years as opposed to 40 years in the other two versions. However, only in the Pisani-Dossi version, is a date explicitly stated. Fiore wrote that he started his composition on February 10, 1409 (1410 using the modern calendar) and alludes to taking approximately six months to complete. Was the difference in the years of Fiore's career an error in the other two versions? It can be argued that such a personal detail would hardly succumb to such an obvious error, and therefore, one can postulate that the Pisani-Dossi version was composed approximately 5 to 10 years after the completion of the Getty's and Morgan's versions, meaning the Getty's and the Morgan's versions were written sometime after the turn of the 14th century. This debate continues with vigour in the historical community and further discussion or research on this particular subject is outside the scope of this paper.

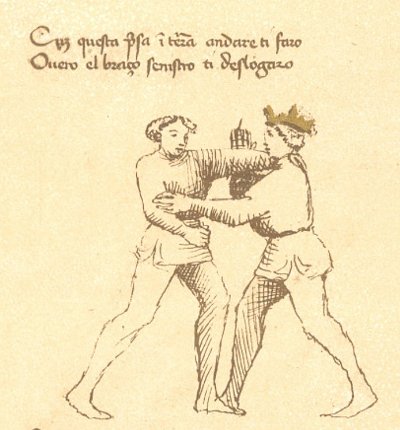

The most extraordinary difference between the Pisani-Dossi and the other versions is in the structure of the text accompanying the illustrations. The text in the Pisani-Dossi is comprised of rhyming couplets (see illustration 2), which gives the impression that the purpose was to inject combative concepts into the fewest and more memorable prose to aid in recalling and remembering the great expanse of armizare. It is the opinion of this author, which is shared by other researchers and practitioners of historical fencing, that the design of this manuscript may have served a similar purpose as mnemonics used to remember details of certain information or facts or concepts, e.g. "Mary's violet eyes make Johnny stay up nights. Period" which was used to remember the names and order of the nine planets (now eight!) in our solar system. The Pisani-Dossi version may have been designed employing memorial techniques consistent with other period writings as memorial cues and aids which may be compared to a conglomeration of mnemonic phrases and the popular “Coles Notes”33 used by students for many years as a study guide and learning aid. Interestingly, approximately 68% of the prologue in the Pisani-Dossi is focused on describing the structure and order of the treatise, as compared to approximately 47% in the Getty's version and only 26% of the prologue describing the structure in the Morgan's version. Such detail in its structure adds credence to the notion that perhaps the Pisani-Dossi version was indeed oriented towards a student's learning and training guide.

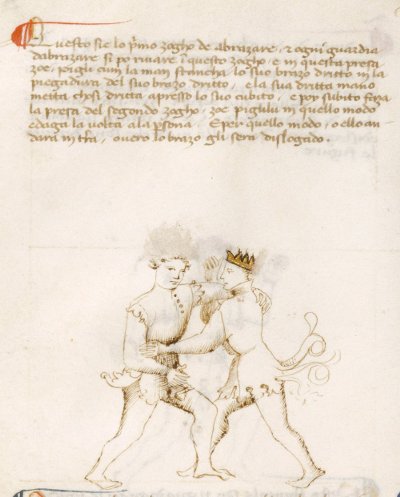

Of the three versions, the Getty's offers the most detailed paragraphs accompanying the illustrations (see illustration 3), followed by the Morgan's with a slightly abbreviated text. To add, the illustrations found in the Getty's and Morgan's are less “animated” like than the illustrations found in the Pisani-Dossi. To add, the contents of the Morgan, despite being more similar to the Getty's version, does not cover the entire art as is within the Getty's, with significant portions not included such as the “abrazare ” (grappling) and “daga ” (dagger) sections found in both the Pisani-Dossi and Getty's.

A more detailed examination of the presentation of the First Remedy Master of the first play of abrazare follows. The text accompanying the figure illustrated in Figure #2 above, from the Pisani-Dossi version reads as:

Cum questa presa in terra andare ti farò

Ouero el braço senistro ti deslogaro34

which translated becomes:

I will make you go to the ground with this hold

Or else I will dislocate your left arm

Although, the couplet is not as much a mnenomic as it is a simplified verse to convey a particular principle with respect to the classic shoulder grab and the counter to such an attack. The couplet can easily be translated into physical reality by a student of the art. Continuing on with the Getty's text accompanying the same figures in its version, it reads as:

Questo sie lo primo zogho de abrazare et ogni guardia

d'abrazare si po 'riuare in questo zogho e in questa presa

zoe pigli cum la man stancha lo suo brazo dritto in la

piegadura del suo brazo dritto e la sua dritta mano

metta chosi dritta apresso lo suo cubito e poy subito faza

la presa del segondo zogho zoe piglilu in quello modo

e daga la uolta ala persona E per quello modo o ello an-

dara in terra ouero lo brazo gli serà dislogado.

which translated becomes:

This is the first play of abrazare and every guard

of abrazare can arrive in this play and in this hold35

namely take hold with the left hand his right arm in the

fold/bend of his right arm and your right hand

is put like this right behind his elbow and then suddenly I will make

the hold “presa” of the second play namely I catch him in this way

and give a turn to his body and in this way I have him

go to the ground or I shall dislocate the arm of his.

Interestingly, the text in the Pisani-Dossi version essentially describes the same action as the Getty's version, with much less text in the form of a rhyming couplet providing a memory aid and relying on the illustrations to ensure the point gets across. Whereas the Getty's text offers more detailed description and examination of the subtleties of the actions involved accompanying the illustration which were rendered with greater sophistication as compared to the former treatise. Yet both versions conveys a very similar concept and achieves the same instructional objective for this particular play. This is consistent across the entire Pisani-Dossi and Getty's treatises.

The examination of the Morgan's version, as compared to the Getty's will reveal that the Morgan's text is near word-for-word similar to the Gettys', however, the organization of the Morgan's is completely different from the Getty's in that it begins with a section on combats on horseback with lances, whereas, the Getty's begins with abrazare or grappling. The Morgan's is also the shortest of the three treatises, whereby, the abrazare and daga sections are completely absent, however, there are plates which depict wrestling on horseback and some plates depicting dagger against sword.

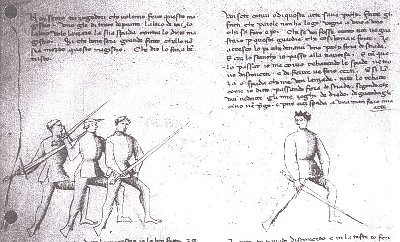

The general thinking as to why the Morgan's is so much shorter than the other two, was that it was probable that the manuscript was not completed due to lack of funds or events which precluded its completion. Perhaps other projects took precedence and the Morgan's version was left as an incomplete manuscript. To add, there is neither dedication in the prologue to a Patron nor any mention of Nicolo III. From the Morgan's version referring to the "3 players" illustrated in Figure 4:

Noy semo tri zugadori che volemo ferir questo

magistro. Uno glie de' trare de punta l'altro de taglio

l'altro vole lanzare la sua spada contra lo ditto

magistro. Sì che bene serà grande fatto ch'ello non sia

morto questo magistro che dio lo faza ben tristo.Voi sete cativi e di questa arte save pocho, fate gli

fatti che parole non ha logo, vegna a uno a uno chi sa

fare e pò che se vui foste cento tuti ve guastarò per

questa guardia ch'è così bona e forte. Io acresco lo pe'

ch'è denanci uno pocho fora de strada, e cum lo

stancho io passo alla traversa. E cum quelo passar io

me covro rebatendo le spade ve trovo discoverti e de

ferire ve farò certi. E si lanza o spada che me ven

lanzada, tute le rebatto come i' ò ditto passando fora

de strada. segondo che vui vederite gli mie zoghi de

dredo. De guardagli ch'io ven prego, e pure cum

spada a una man farò mia arte.

which translated becomes:

We are three Players that want to hurt this Master.

One he will thrust the point, the other cuts, the

other will throw his sword against the said Master.

As well it is a very great fact that this Master is not

dead that God made him very wily.You have wicked desires and of this art know little,

you especially do things that have no place in

words, come one by one who knows how to do it

and even if you were one hundred I will ruin you all

because of this guard that is therefore good and

strong. I accrease the foot that is forward a little

out of the way, and with the left I pass to the side.

And with this pass I cover beating the sword and I

find you uncovered and of striking you I will be cer-

tain. And of a spear or sword that is thrown at me,

I will beat them all as I have said passing out of the

way. As you will see in my plays that follow here

after. Look at them I pray to you, and therefore

with the sword of one hand I will make my art.

|

| Figure 4: Morgan - extracted from plate 17R, depicting what is commonly called "three players", often misinterpreted as the master on the right facing three opponents at the same time on the left. |

|

| Figure 5: Getty - extracted from folio 20 depicts the same scenario and technique as found in the Morgan's version. Copyright © 2008 The J. Paul Getty Trust. All rights reserved. |

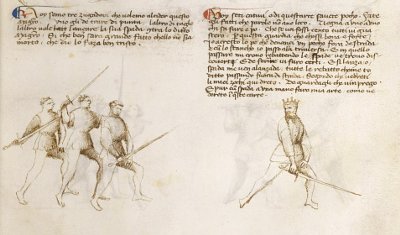

From the Getty's version referring to the "3 players" in Figure 5:

Noy semo tre zugadori che volemo alcider questo

magistro. Uno gli dè trare di punta, l’altro di taglio

l’altro vole fatt lanzare la sua spada contra lo ditto

magistro. Sì che ben sarà grande fatto ch’ello non sia

morto che dio lo faza ben tristoVoy seti cativi e di quest’arte savete pocho. Fate gli

che parole non ano loco. Vegna a uno a uno chi sa fare

e po’ che se voi fossi cento tutti vi guasterò per questa

guardia ch’è chossì bona e forte. Io acresco lo pe' ch’è

denanci un pocho fora de strada e cum lo stancho io

passo ala traversa. E in quello passare incroso

rebattendo le spade ve trovo discoverti e de ferire vi

farò certi. E si lanza o spada me ven alanzada,

tutte le rebatto chome t’ò ditto passando fuora di

strada, segondo che vedreti li miei zochi qui dreto,

de guardagli che v'in prego. E pur cum spada a una

mano farò mia arte como n’è dereto in queste carte.

which translated becomes:

We are three Players that intend to kill this Master.

One will throw the point (thrust), the other with a cut,

the other wants to throw his sword against the said

Master. So that it will be a very great fact he is not

dead that God makes him very sorrowful.You have bad desires and of this art you know little.

You do things that have no place in words. Come

one by one who knows how to do it and even if you

were one hundred I will put you all out of order

because of this guard that is so good and strong.

I accrease the foot that is forward a little out of the

way and with the left I pass to the side (traverse).

And in that pass I cross beating the sword to you I

find you revealed and of wounding you I will make

certain. And if a spear or sword is thrown at me,

I will beat them all like I have said passing out of the

way. As you will see in my plays that follow here

after, I pray that you look at them. And even with a

one handed sword I will do my art as it is after in

these papers.

The differences between the two versions as depicted above is minimal. The language has some differences, and may be attributed to differences in the "dialect", hence the slight differences in the language. This particular play has often been misinterpreted as the master, possessing the skills of the art is able to face three fighters at the same time. The illustration and text actually reveal that the particular "posta " or guard which the master has assumed is able to defend and offend an attack from any one of the originating offensive stances.

In Conclusion

Although Fiore dei Liberi was merely a footnote in the annals of history, definitely not in the same league as some of the great men of the period, however, his influence in the 21st century can be vividly seen and experienced across many historical fighting and fencing schools and academies throughout the world. The challenge of rebuilding the man who bore the name Fiore will require exhaustive research into archives, personal collections and libraries which remain untouched or inaccessible today with respect to research on the man Fiore. By cultivating a more complete and detailed biography of Fiore, will most definitely aid in our understanding, development and evolution of armizare, perhaps ensuring that the resurrected form of armizare is closer to the “truth” as expected by Fiore himself.

Lastly, the reconstruction and practice of armizare cannot be complete without referencing and studying all three treatises. Each has certain unique qualities and attributes which contribute to fleshing out the art. It is hoped that as we learn more about Fiore, through closer examination of the treatises and through research of secondary sources such as archived records and documents, armizare will once again re-acquire its original status as a complete and viable offensive and defensive fighting art system – a viable alternative to today's popular Eastern systems.

Notes

- Fiore never revealed a formal name of the art in the treatises, simply referring to it as l`arte dell`armizare which is briefly referred to as armizare.

- At this time, there has been no formal academic study of the treatises or on Fiore deil Liberi. All materials available on this subject are the result of significant collective research efforts by individuals within a number of schools and academies world wide including but not limited to: The Exiles CMMA (UK), Schola Gladiatoria (UK), Compagnia de'Malipiero (Italy), Chicago Swordplay Guild (USA) and the Academy of European Medieval Martial Arts (Canada).

- As of early September 2008, a 4th version of the treatise had been revealed to the Western Martial Arts Community: Florius de arte luctandi: MSS LATIN 11269, Bibliotéque nationale de France (BNS), however, this paper will only focus on three versions of Fiore's work, so named by the collection the treatise resides. Further examination of the treatises occurs later in this paper, however, for the purpose of convenience at this point, the three versions are: Getty-Ludwig version, MS Ludwig XV13 located in the John Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, USA; Morgan version, MS M. 383, Pierpoint-Morgan Library, New York City, USA; Pisani-Dossi version, of the F. Novati collection.

- “dei Liberi” which means “of the family of the Liberi” implies that the Liberi family had some measure of a noble status at that time, however, it is not clear from what is written of the extent of the noble status without conducting further detailed research on relevant municipal records and documents found in Premariacco, Udine and Cividale del Friuli. It is assumed that the Liberi family was of modest noble standing.

- The Patriarchate of Aquileia located in the extreme north-east of Italy was a former city of the RomanEmpire, situated at the head of the Adriatic, on what is now the Austrian sea-coast, in the country of Goerz (Goricia in Slovenia) was initially formed during the Roman Empire sometime around 70AD, and which had been a force in the Christian church for centuries. Without going into details, the Church was an important and prominant part of medieval life, and therefore, would appear in Fiore's treatise as an important and customary detail. The Church throughout history maintained detailed records, in particular, births and deaths of its patrons, and therefore, it may be possible to locate records, if they still exist and available to determine more accurately the birth and death of Fiore and/or his family members.

- This phrase is extracted from the “alter prologus” in the Pisani-Dossi version. By virtue of the title “meser” is not unlike the title of “Sir” used today, which indicates a man of noble origin.

- Friuli is a region located in the north-eastern portion of Italy neighbouring Slovenia, known as Furlanija (Slovenian) or Friaul (German) has as its most important city, Udine. Friuli also includes the village of Premariacco, which is located approximately 13km east of Udine. Cividale d'Austria (now named as Cividale del Friuli) is adjact to the river Natisone and is located approximately 15km east of Udine close to the border of Slovenia.

- Despite the common subject across the three versions of the treatise, some differences do surface. For example, in the Pisani-Dossi version, the text describes Fiore's fighting career as more than 50 years, yet in the Getty's and Morgan's version, it is described as being for more than 40 years. This may imply that the manuscripts may have been written in different years and therefore, the versions represents not copies/versions of a single original treatise, but are intances of of a number of treatises by Fiore, perhaps each created for a different purpose or patron.

- This has been a source of great discussion in the historical fencing community of the word “suueno ” which may indicate Master Johane was of German origin, more specifically, from Swabia. One line of thought is that Johane of Swabia may in fact be Johannes Liechteneaur, a swordsmaster from the mid-14th century, however, the timing isn't quite right, as Fiore would've been born around that time. To add to the confusion, Fiore wrote that Master Johane was a student of Master Nicholai of Toblem, which would mean that Master Nicholai was Liechtenauer's instructor, and there is no mention of Master Nicholai in German treatises, although, Liechtenauer's lineage has been mapped out with respect to German longsword tradition (Hans-Peter Hils, 1985). To date, there are no other records nor documents which offer clues to flesh out Master Nicholai's or Master Johane's biographical data.

- Preliminary examination by practitioner and researcher, Matt Galas (Belgium, August 2005) indicated that the Diocese Mexinensis was not found in period and modern texts as spelled in the treatise, however, he did discover names “close” to Fiore's written text which may be one of Mechlinensis (Mechelen in Belgium); Megenensis / Meginensis campus (the former district of Mayenfeld on the lower Mosel river); Mexentiae pons (Pont-Sainte-Maxence in France), Misnensis (Meissen in Saxony); and Metensis (Metz in Lorraine). The going forward assumption was that Toblem was of German heritage. However, recent discussions (Ariella Eleman, Toronto & Fabrice Cognot, Belgium, 2006) appear to have vapourized that assumption with suggestions that the Diocese of Mexinensis may infact be referring to Messina and which may be supported by Graesse's Orbis Latinus (1909 – a dictionary of Latin placenames and their vernacular equivalents). This paper is not intended to crystalize the biography of Fiore, however, it is evident that the fragments of information found in Fiore's prologue will require further significant direct and related research effort, as well as a detailed linguistic study of Friulian, in order to tease out more details originating from supporting historical sources necessary to flesh out Fiore's biography.

- G. Zanutto, an historian who conducted research into Fiore's past and who authored a book on his research entitled “Fiore dei Liberi da Premariacco e i ludi e le fest marziali in Friuli. ”, published in 1907.

- A fascinating piece of documentation research and retrieval by Zanutto in which records found in the Municipal Archive of Udine, VII, f.208 v dated September 30, 1383 indicated that after deliberation by the town council, Fiore was tasked to take charge of the crossbow-men and artilery including the ballista.

- The brief accounts describing feats of arms were written in the prologue of the Getty's and Morgan's versions, but visibly absent in the Pisani-Dossi version.

- miß piero dal uerde (Morgan) / Missier piero del verde (Getty)

- miser piero dala corona (Morgan) / Missier piero dela corona (Getty)

- Fiore refers to Germans as “todeschi ”. Given the political and historical landscape at the time, there was little distinction between German and Swabian, all collectively refered to as “todeschi ”.

- miß Galeaz delli capitani de grimello chiamado da Mantoa (Morgan) / Missie Galeaco di Captani di Grimello chiamado da Mantoa (Getty)

- miser Bricichardo de Franza (Morgan) / Missier Bucichardo de fraca (Getty)

- Fiore's prologue does not reveal dates of the duels, however, a detailed account of this duel describing the traditional protocol and ceremony surrounding this form of duel held before Lords of Padua, Mantua Ravena and Lord Carlo Malatesta, a notable condottiere, and which ended non-fatally despite Boucicault receiving a thrust by a spear wielded by Galeazzo in the camail around the shoulder. The extent of the injury incurred, if at all, was not revealed in the account but the duel was immediately halted by the Lords and peace was made between Galeazzo and Boucicault. Galeazzo and Bartolomeo Gatari, Cronaca carrarese, ed. Medin and Tolomei, pp. 83, 448-9.

- miser Nicholo Vnricilino (Morgan) / Missier Nicol Voricilino (Getty)

- nicholo Inghileso (Morgan) / nicolo Inghileso (Getty)

- Lancilotto (Lanzilotto de Boecharia da Pavia (Morgan) / Lancilotto da Becharia de Pauia (Getty)) may have made an appearance in a 15c German Armorial (Latin MS 28, University of Manchester, Ryland Collection Library). However, only some of the plates are visible in the online collection and no text describing the arms are available at least online, and therefore, qualifying this potential lead will require more effort which is outside the scope of this paper. The arms are included for reference and interest only.

- miß Baldesar (Morgan) / Missier Baldassaro (Getty)

- Zohanni de Baio da Milano (Morgan) / çoanino da Bayo da Milano (Getty)

- Probably referring to “rebated” weapons which were incapable of taking an edge, often employed in tournaments.

- miser Azo da Castelbarcho (Morgan) / Missier Açço da Castell Barcho (Getty)

- miß Zohanni di li ordelaffig (Morgan) / çuanne di Ordelaffi (Getty)

- miß Jacomo da Besen (Morgan) / Missier Jacomo di Boson (Getty)

- An arming doublet is a long-sleeved padded jacket worn under armour, often fitted with arming points to which plate armour would've been tied to. Fiore mentioned in his prologue that his preference was to fight in armour because it was far more forgiving should the combatant make a mistake by virtue of the protection offered by the plate armour and stated that he would rather fight three times in armour in the barriers than a single unarmoured duel with a sharp sword.

- Nicolo III, born on 9 November 1383. at the age of 10 years inherited from Alberto V, his father when he died in1394, the head of the Estense state whose dominions at that time included Ferrara, Modena, Adria, Comacchio, Rovigo and various possessions in Romagna.

- The provenance listed for the Morgan version is extracted from the cover information page describing the manuscript from the Pierpoint Morgan Library Dept. Of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts, and which describes the source of the provenance listed in that document from the publication by Francesco Novati, 1902.

- The provenance listed for the Getty version is extracted from Matt Easton's website http://www.fioredeiliberi.org/fiore/ which was originally compiled by Matt Galas.

- Coles Notes were first published in 1948 in the UK, and is now owned by Indigo Books in Canada. Coles Notes served a similar function to the American's version called “Cliff Notes” first published in 1958.

- Much of the transcriptions from the script found in the treatises were extracted from Rubboli, Marco & Luca Cesari. “Flos Duellatorum – Manuale di arte del combattimento del XV secolo”. Il Cerchio. 2002. These transcriptions are more or less consistent with the many other transcriptions available online in the Internet and some minor corrections were edited into the transcriptions to improve their consistency with the original text.

- In this context, “hold” is a noun describing a “thing” referring to a grab or “presa”. There are no other appropriate English words to describe the “thing”, whereas, continuing in the same statement, the next instance of “hold” describes an action.

Bibliography

Carruthers, Mary J. The Book of Memory – A Study of Memory in Medieval Culture. Cambridge University Press. 1990.

Cvet, David M. The Measure of a Master Swordsman. Journal of Western Martial Art. http://www.ejmas.com/jwma/articles/2005/jwmaart_cvet_0105.htm (accessed August 28, 2008)

Dean, Trevor. Crime and Justice in Late Medieval Italy. Canbridge University Press. 2007.

Easton, Mat. Fiore dei Liberi. http://www.fioredeiliberi.org/fiore/ (accessed July 20, 2008).

Fior di Battaglia: MS M.383 - The Pierpoint Morgan Library (codice "MORGAN").

Fior di Battaglia: MS Ludwig XV 13 - J. Paul Getty Museum (codice "GETTY").

Flos Duellatorum (Pisani-Dossi MS): F. Novati, Flos duellatorum: Il Fior di battaglia di maestro Fiore dei Liberi da Premariacco (Bergamo, 1902).

Florio, John. Queen Anna's New World of Words Or Dictionarie of the Italian and English Tongues. London. Printed by Melch. Bradwood for Edw. Blount and William Barres. 1611.

The Getty. The Flower of Battle. http://www.getty.edu/art/gettyguide/artObjectDetails?artobj=1706 (accessed June 26, 2008).

Hils, Hans-Peter. Meister Johann Liechtenauers Kunst des langen Schwertes. 1985.

Howe, Russ. Fiore dei Liberi : Origins and Motivations. Journal of Western Martial Art, http://www.ejmas.com/jwma/articles/2008/jwmaart_howe_0808.htm (accessed September 4, 2008)

Lovett, Robert. The Exiles Fiore Project. http://www.the-exiles.org/FioreProject/Project.htm (accessed May 10, 2008).

Malipiero, Massimo. Il Fiore di battaglia di Fiore dei Liberi da Cividale. Ribis. 2006.

Michelini, Hermes & Shire, Mich. Fiore de' Liberi The Flower of Battles. http://www.aemma.org/onlineResources/liberi/wildRose/fiore.html (accessed January 21, 2008)

Rubboli, Marco & Luca Cesari. Flos Duellatorum – Manuale di arte del combattimento del XV secolo. Il Cerchio. 2002.

Zanutto, G. Fiore dei Liberi da Premariacco e i ludi e le fest marziali in Friuli. Udine 1907.

About the author: is the Founder, President and Provost of the Academy of European Medieval Martial Arts (AEMMA), an organization dedicated to the resurrection and formalization of medieval martial arts training systems. He received training in Milan, Italy employing steel weapons in longsword techniques and has participated in various organizations dedicated to studying the Middle Ages. His background and experience having fired his desire to pursue a formal medieval martial arts training program, he founded AEMMA in mid-1998. He is a member of the advisory board of the Swordplay Symposium International (SSI), an interdisciplinary colloquium of historical fencing specialists dedicated to promoting and advancing the study of Western swordsmanship, and participating board member of the Association for Historical Fencing (AHF). David received his appointment of free scholler in Oct, 2000 and the "Acknowledged Instructor" (AI) designation for armoured combat instruction in Oct, 2000 by the International Masters at Arms Federation (IMAF).

About the author: is the Founder, President and Provost of the Academy of European Medieval Martial Arts (AEMMA), an organization dedicated to the resurrection and formalization of medieval martial arts training systems. He received training in Milan, Italy employing steel weapons in longsword techniques and has participated in various organizations dedicated to studying the Middle Ages. His background and experience having fired his desire to pursue a formal medieval martial arts training program, he founded AEMMA in mid-1998. He is a member of the advisory board of the Swordplay Symposium International (SSI), an interdisciplinary colloquium of historical fencing specialists dedicated to promoting and advancing the study of Western swordsmanship, and participating board member of the Association for Historical Fencing (AHF). David received his appointment of free scholler in Oct, 2000 and the "Acknowledged Instructor" (AI) designation for armoured combat instruction in Oct, 2000 by the International Masters at Arms Federation (IMAF).

Journal of Western Martial Art

September 2008

EJMAS Copyright © 2008 All Rights Reserved