Reflections on audatia as a Martial Virtue

Journal of Western Martial Art

September 2006

by Dr. Charles H. Hackney

Fiore Friulano dei Liberi, in the prologue of his treatise, Flos Duellatorum ("Flower of Battle"), describes his early life in the small town of Cividale. Wishing to learn swordsmanship from the best instructors available, he left the northern Italian village of his birth. In his travels, he trained under numerous German and Italian masters of defense, Master Giovanni Suveno (Johannes Suvenus) being the most prominent. After two decades of experience as a soldier and duelist, he eventually entered the court of Niccolo of Este, the Marquis of Ferrara, where he acquired a commission in the early 1400s as a master swordsman. He then began to write his manuscript, in which he describes the techniques central to his approach to the martial arts. The treatise was completed in 1410, and dedicated to the Marquis. Current students of medieval European martial arts often look to Flos Duellatorum as a guide and training manual, and many consider it to be without equal among pre-Renaissance manuscripts on the arts of defense (Kautz, 2001).

In a manner typical of premodern approaches (Hamilton, 1955), Liberi lists and describes ideal virtues of an excellent practitioner of his art. While four virtues are emphasized elsewhere in Liberi’s treatise (Cvet, 2005), he focuses on one singular virtue in the prologue of the Pisani-Dossi version of the manuscript, calling it "the virtue that makes this art" (Lovett, Davidson, & Lancaster, 2005). The virtue which Liberi elevates to this core status is audatia, typically translated as "audacity." The use of this term may strike readers as odd. In common use, "audacity" carries with it the connotation of thoughtlessly trampling standards of polite behavior, which seems to have questionable applicability to the martial arts, and is certainly not characteristic of a gentleman.

In a manner typical of premodern approaches (Hamilton, 1955), Liberi lists and describes ideal virtues of an excellent practitioner of his art. While four virtues are emphasized elsewhere in Liberi’s treatise (Cvet, 2005), he focuses on one singular virtue in the prologue of the Pisani-Dossi version of the manuscript, calling it "the virtue that makes this art" (Lovett, Davidson, & Lancaster, 2005). The virtue which Liberi elevates to this core status is audatia, typically translated as "audacity." The use of this term may strike readers as odd. In common use, "audacity" carries with it the connotation of thoughtlessly trampling standards of polite behavior, which seems to have questionable applicability to the martial arts, and is certainly not characteristic of a gentleman.

It is the purpose of this essay to examine, from a variety of perspectives, Liberi’s use of the term audatia. Examination of this virtue will draw primarily from the philosophical and psychological literature, as virtue theories are currently gaining ground in these fields (Fowers & Tjeltveit, 2003). It is hoped that these theories may shed some light on the nature of audatia, how it may be cultivated, and how it may be applied in the life of a martial artist.

Virtue Theories

Virtue-centered theories of character development and moral philosophy within Western thought consider the ethical writings of Aristotle as their foundation stone. In the latter part of the twentieth century, Aristotelian virtue ethics experienced a revival in scholarly circles (Spohn, 1992), with primary credit most often given to the work of philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre, and his revolutionary book After Virtue (MacIntyre, 1984). In After Virtue, MacIntyre traces the decline of Aristotelian thinking in Western ethics, culminating in the seventeenth through nineteenth centuries’ "Enlightenment Project." The goal of this Project was to provide a universal rational justification of morality without reference to historical or social context. MacIntyre sees in Nietzsche the final failure of that Project. The failure of the Enlightenment Project prompts MacIntyre to advocate a return to the Aristotelian tradition in Western ethical thought.

The Aristotelian approach is teleological in nature. In his Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle begins his analysis with the idea that every activity aims at some goal (telos), and that ethical evaluations can be understood in terms of that purpose. To call something "good" is to say that it accomplishes its purpose. A good watch keeps time well. A good horse runs well. A good person can be evaluated from a similar perspective, so moral philosophy should center around identifying the human telos and the means by which people can advance toward that developmental goal. Virtues are character traits that facilitate a person’s growth toward the telos, enabling them to live well.

This emphasis on virtues as positive traits has been applied to areas beyond philosophy, especially in the human sciences. Peterson and Seligman (2004), for example, draw heavily on virtue ethics in their research into strengths of personality that facilitate emotional growth and buffer against mental illness. Cameron, Bright, and Caza (2004) employ a virtue perspective in the field of business and organizational studies. Dueck and Riemer (2003) explore the virtues in psychotherapy. Higgins (2003) examines how MacIntyre’s approach might be applied to education.

Most work done relating to the virtues has centered around the overall question of human nature, what the universal human telos might be, and what catalog of virtues enables a person to be a good person. Examples of this universalist approach include Dahlsgaard, Peterson, and Seligman’s (2005) cross-cultural research, resulting in a list of six cross-culturally ubiquitous virtues (courage, justice, humanity, temperance, wisdom, and transcendence). Others have focused on attempting to identify a single "master" virtue that guides subordinate virtues, such as Fowers’ (2005) emphasis on phronesis (practical wisdom) and Peterson’s (2006) placement of love above the other virtues.

Some scholars have also focused more narrowly on virtues that operate within particular traditions and communities. MacIntyre (1984) puts forward the idea that all approaches to virtues must take into account the telos toward which the person is striving, and that our understanding of the telos is shaped by the social group in which we find ourselves. Examples of this include Sundararajan’s (2005) examination of "emptiness" as a uniquely-Buddhist virtue, Hauerwas and Pinches’ (1997) discussion of megalopsuchia ("great-souled" magnanimity) as unique to classical Athens, Murphy’s (2005) work on the Christian virtue of kenosis (self-emptying), and Mohatt, Hazel, and Allen’s (2004) research involving ellangneq (a Yup’ik virtue involving awareness of social interconnectivity and responsibility).

It is this particularist focus which I intend to employ in this examination of audatia. The community within which this virtue will be applied is the transcultural tradition of martial arts in general, western martial arts more specifically, and most specifically within the study of Fiore dei Liberi’s system. I argue that the martial arts may be considered a community (or several discrete communities sharing a strong "family resemblance") within a MacIntyrean approach, as they can be examined in terms of MacIntyre’s description of the constituent elements of a community: practices, traditions, narratives, and virtues (Kallenberg, 1997).

Examples of practices that constitute the martial arts include group training, solitary practice, and the study of formative texts (fechbuchen, densho, manuals, biographies, etc).

Traditions within the martial arts are given considerable importance, and are often subject of argument between practitioners. The specific style (or "school," "ryu," etc) to which the martial artist adheres may be considered (and is often explicitly self-identified as) a tradition which shapes not only the martial artist’s style of fighting, but also the character of the martial artist. Consider George Silver’s (1599) argument that the aggressive style taught by the Italian fencing masters produces belligerent students.

Narratives provide structure for traditions, and context for practices. MacIntyre (1984) makes the claim that the question "what ought I do?" can only be answered once the prior question "of what story do I find myself a part?" has been answered. Narratives can include the history of the community as told by members of the community, which may or may not be historically accurate. See the discussion of chivalric literature in Price (2000), and Keen’s (1984) examination of the historical mythology of chivalry, for medieval European examples. Narratives can also be the "life stories" by which individuals within a community define themselves. Individuals’ self-narratives within the martial arts center around the reasons why they train, and what they are attempting to accomplish. Martial artists may, for a few examples, see themselves as embarked on a quest for spiritual enlightenment (Maliszewski, 1996), as a "living antique" displaying the past for the benefit of the present (Lowry, 1985), or involved in the overall improvement of the self (Karamyar, 2005).

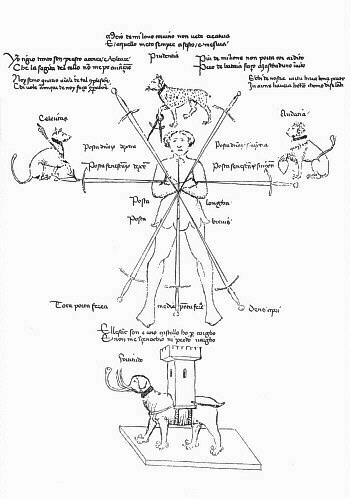

Discussion of "warrior virtues," character traits that facilitate the martial artist’s advancement, demonstrate ubiquity across history and culture. MacIntyre (1984) examines the epics of Homer, discussing some of the "heroic virtues" (courage, morbid fatalism, loyalty, intelligence, strength) upheld by 6th-century BC Greek society. Keens (1984), drawing from a 15th-century French manuscript, lists prouesse (prowess), loyaute (loyalty), largesse (generosity), courtoisie (courtesy), and franchise (an open and frank bearing) as the "classic virtues of good knighthood." Nitobe’s (1969) classic text on bushido makes extensive use of virtue terms in describing Japan’s warrior code, focusing on virtues such as justice, courage, benevolence, politeness, loyalty, and self-control. The "four creatures" illustration in Flos Duellatorum, representing the four "meta-physical attributes" (Cvet, 2005) of prudence, speed, courage, and strength, could also be considered as Liberi’s catalog of warrior virtues.

Audacity as a Warrior Virtue

In the prologue to the Pisani-Dossi version of Flos Duellatorum, Liberi writes: "Audatia et virtus talis consistit in arte," which is translated by Lovett, Davidson, and Lancaster (2005) as "Audacity is the virtue that makes this art." This is the final line in a nine-line poem in which audatia (and the variant audax) features prominently in the author’s admonition to avoid fear by cultivating audacity in the heart.

Audatia also appears in Liberi’s aforementioned "four creatures" illustration. It appears beside the image of a lion, with a reference to the lion’s daring heart. At this point in the manuscript, audatia is typically translated as "courage," though "audacity" remains a less often-used option (Cvet, 2005). Cvet (ibid.) suggests that the placement of the lion to the left of the illustration may have been to emphasize its status as secondary to other virtues. While I certainly agree with Cvet’s claim that audacity must be balanced by virtues such as prudence, Liberi’s elevation of audacity in the prologue seems to speak against audacity’s secondary status.

Audatia is derived from the Latin audacia, which is also typically translated as "audacity" (Lewis & Short, 1955). As mentioned above, this term is conceptually problematic, as it carries the connotation of rudeness in common usage. A survey of Latin dictionaries indicates a similar ambiguity, in which the most common meaning of audacia is negative in nature, indicating temerity and impudence. Only in a secondary sense is audacia taken to mean intrepidity and daring (Simpson, 1977). Smith and Hall (1871), in fact, make a point of contrasting audacia ("simple daring") against courage, for which they prefer the words fortitudo or animus. Other sources (Lewis & Short, 1955; Simpson, 1977) reserve fortitudo for physical acts of strength and bravery, and animus for strength as a component of masculinity. Taken together, these treatments of the word audacia support the notion that audatia may not necessarily refer to courage in general, but more specifically to daring boldness.

This argument, however, does not divorce audacity entirely from courage. Courage takes many forms. The courage of a crusading social reformer is not identical to the courage of a soldier in the field, which is not identical to the courage of a battered woman leaving an abusive husband, which is not identical to the courage of a teenager resisting peer pressure. As demonstrated in Peterson and Seligman’s (2004) chapters on courage, this virtue can manifest itself in numerous variations and subtypes in a wide range of possible applications.

The common thread in the varieties of courage is the ability to overcome varieties of fear. The centrality of this commonality is consistent with Peterson and Seligman’s (ibid.) assertion that virtues are inherently corrective in nature. We cultivate virtues as a means of overcoming natural human weaknesses. We strive for wisdom because we are born ignorant. We cultivate temperance because our untutored inclination is toward self-indulgence. We are naturally fearful, so we need courage. In Liberi’s poem, the target of this investigation, fear is mentioned three times as the characteristic one should avoid. Audacity is the prescribed corrective.

Based on the etymological, philosophical, and psychological work on the topic of courage, it is my assertion that audatia refers to one of the specific forms of courage. Audacity is the form of courage that enables the martial artist to overcome fear in the midst of fighting, so as to act decisively and without hesitation.

Before proceeding to practical considerations, I will take a moment to consider audacity outside of the European tradition. This is intended to support the idea that, although the bulk of this essay has focused on audacity within Liberi’s art, this virtue is applicable to the broader community of martial arts. A truly cross-cultural examination would be a study in itself, so in the interest of brevity I will restrict my comments to only a few instances of audatia within Japanese contexts.

Audacity in Japanese Martial Arts

The Book of Five Rings was written by legendary samurai Miyamoto Musashi in the mid 17th century. After a lifetime of combat, Musashi entered into a period of reflection and study, and this text is the culmination of his introspective analysis (Musashi, 1994). The book is divided into five sections, corresponding to the five classical elements (earth, water, fire, air, and void) of the metaphysics of that period. Although the bulk of the book contains practical advice rather than theories of virtue, several of Musassashi’s teachings can be interpreted along virtuous lines (see Slingerland, 2001, and Dahlsgaard, Peterson, & Seligman, 2005, for other examples of inferring virtues from historical texts). Many of these teachings can be seen as advocating qualities reminiscent of audacity, including his admonition to aspiring warriors to move from technique to technique without hesitation (Musashi, 1994, p. 51), and his advice that "as soon as you sense the possibility of an attack, you must react immediately with your own attack to kill the enemy or you will give him the chance to regather himself and come at you again" (p. 64).

Early in the 18th century, a young samurai, Tashiro Tsuramoto, recorded the teachings of an elder samurai, Yamamoto Tsunetomo. These teachings were collected into the volume Hagakure (Tsunetomo, 1979). Hagakure is also not a systematic ethical philosophy, but rather a somewhat-scattered collection of sayings, so a virtue-centered analysis will also involve interpreting specific teachings as indicative of virtues. The virtue of audacity can be seen in the author’s statements that "when meeting difficult situations, one should dash forward bravely and with joy" (p. 45), and that "the way of the samurai is one of immediacy, and it is best to dash in headlong" (p. 60).

For a contemporary example, Masaaki Hatsumi, the current Grandmaster of the Bujinkan, encourages students not to "focus on trying to ‘get’ techniques on your opponent. Try to flow into the techniques as they present themselves" (Hatsumi & Cole, 2001, p. 90), and "don’t hesitate and don’t hold back. In a real confrontation, if you do, you die" (p. 252). Dave Lowry (2000) employs virtue-like language, dedicating a chapter of his book Moving Toward Stillness to the Japanese term jikishin, which he translates as "direct mind." Lowry describes jikishin as a characteristic of an effective fighter, one that involves responding to attacks instantly and with "absolute intensity" (p. 59).

Applicatory Venues for audatia

The most obvious area of practical application of this virtue is self-defense. Cultivating audacity increases the likelihood that, when faced with the necessity of acting in response to a genuine assault, the martial artist will respond with swift and decisive action rather than panic and confusion. A primary piece of evidence for the utility of this virtue for "real-world fighting" is its ubiquity in manuscripts prepared by masters of defense across the centuries. If we accept, for example, that Miyamoto Musashi survived over sixty life-and-death fights, or that Fiore dei Liberi spent the last two decades of the 14th century as a soldier and duelist, then we may be inclined to believe that they speak from experience when describing the characteristics of an excellent fighter. When the writings of a 14th-century swordmaster and a 17th-century samurai line up with the comments of a 20th-century US Navy SEAL (Marcinko, 1996) about the necessity of training to act decisively despite the fear and confusion of a chaotic combat situation (p. 62), and of a former FBI agent’s (Liddy, 1980) similar reminiscences about handgun training (p. 95-99), that speaks volumes.

Much has been written about how depth of study in the martial arts overlaps with practices in daily life (e.g., Lee, 1975; Lowry, 2000). I will focus on the practice that I believe to be most applicable to the demonstration of audacity in everyday life, that of taking advantage of opportunities. This may include a willingness to speak up when the situation calls for it. Many of us have had the experience of cautiously holding our tongue, resulting in a missed opportunity (e.g., asking someone out for a date) or an unmet challenge (e.g., not standing up for one’s beliefs in a conversation). Those of us who have had such experiences typically spend that night wishing that we had said something. Translating audacity in combat to audacity in speech, Tsunetomo (1979) urges readers that "when there is something to be said, it is better if it is said right away. If it is said later, it will sound like an excuse" (p. 151). However, I am not advocating that we become obnoxious loudmouths. As Cvet (2005) discussed, audacity untempered by prudence leads to recklessness. In combat, recklessness can result in death; in conversation, it is relationships that can be killed by unthinking words. Instead, what I am advocating is that we have the audacity to speak when it is appropriate, in addition to having the wisdom to remain silent when silence is called for.

Nonverbal opportunities for audacity can involve political or social action. Seeing a persistent injustice and thinking that "someone should do something" accomplishes nothing. In the second chapter of the Analects, Confucius offers the aphorism that "to see what is right and not to do it is want of courage," and history is replete with examples of heroic individuals who had the audacity to contradict convention in the name of justice. Altruistic actions are also facilitated by the development of audacity. For example, the decision of whether or not to stop and assist a stranded motorist on the side of the highway is made in a matter of seconds. A classic psychological study (Darley & Batson, 1973) found that, when put under time pressure, participants stepped right over strangers in need of help in order to reach their destination (what makes this study classic is that the participants were seminary students, and the destination was a talk on the parable of the Good Samaritan!). Perhaps the cultivation of audacious altruism could have counteracted this pattern. On a lighter note, audacity may also assist in the initiation of fun activities on the spur of the moment, leading to a greater enjoyment of life.

Practices to Assist in Developing audatia

Studies of other virtues (e.g., Muraven, Baumeister, & Tice, 1999, which focused on self-control) indicate that incorporating certain practices into everyday life can result in measurable increases in the relevant virtue. If audacity involves responding to opponents’ attacks without hesitation, are there any everyday practices that can facilitate the development of audacity?

When in the dojo, salle d’armes, gym, etc, training for audacity should prepare us for audacity in combat. Perhaps nothing can truly prepare us for the realty of a self-defense situation, but increasing the likelihood of a swift and daring response to an attack could mean the difference between life and death. This is one of the values of participating in martial arts that incorporate some element of free sparring. We may engage in arguments about exactly how realistic it may be to train in the necessarily-artificial structure of a sparring session, but perhaps one of the most important components of this form of training is simply getting used to responding to a fast-moving weapon or bodily structure aimed at oneself. Virtues are acquired and strengthened through repeated practice (MacIntyre, 1984), and programs that aim at developing specific virtues (e.g., Sternberg, 2001) most often take place in artificial environments (such as classrooms), so we do have reason to believe that being able to respond audaciously when attacked with a blunt training sword assists in the development of this virtue for application in the real world.

Training for audacity requires more than just frequent sparring. Drills, exercises, and forms/kata are also integral to this process. Authors in numerous martial arts, ranging from the jeet kune do of Bruce Lee (1975) to the ninjutsu of Masaaki Hatsumi (2001) to the pistol training of G. Gordon Liddy (1980), all speak as one in their insistence that drills and exercises are to be practiced slowly, with precision and focus. In doing so, the body learns to perform the technique correctly and consistently. Practice ingrains the movement in the practitioner’s neural system, and it can later be performed at full speed. This assists in cultivating audacity in sparring by allowing the practitioner to stop taking the time to think about techniques in the middle of a match. Well-learned reactions appear nearly instantaneous, facilitating the style of fighting described by those who advocate the virtue of audacity.

Translating these concepts into everyday behavior, I would advise students to avoid allowing themselves to become bored and sloppy when drilling. Keep focus, and cultivate precision in movements. But when sparring, stop analyzing and act. The sparring ring is no place to study. The precise and careful attention that is given to technique before the match is what will result in superior performance. In the words of Tsunetomo (1979, p. 153): "Win first, fight later." The sparring ring is also no place for ego or short tempers. Cultivating audacity means taking risks. Taking risks means that one will sometimes lose. Remember that the enemy of audacity is fear. Not only must the fear of taking painful hits be overcome, but also the fear of looking foolish.

Overcoming the fear of looking foolish may also be applied to the cultivation and application of audatia in everyday life. I briefly mentioned the example of a courageous teenager resisting peer pressure, and also the principle of audaciously speaking up when the situation calls for it. Speaking up in defense of one’s beliefs, one’s friends, or a socially-marginalized individual may result in mockery and rejection at the hands of one’s peer group. Audacity facilitates the taking of a principled stance in the face of derision and ostracism.

Leming (2000) examines the role that literature plays in the development of character, finding that a program based on stories, emphasizing discussion and reflection on ethical matters and positive character attributes, resulted in positive developmental progress in students. By reading narratives, and identifying with the protagonist, readers enter into an emotionally-malleable state, increasing the likelihood that they will incorporate the loves, hates, values, and characteristics of the identified character (Cain, 2005), which makes the reading of books a powerful tool in the cultivation of the virtues (Carr, 2005). This approach to virtuous development can be applied to the cultivation of audatia in much the same way as it has been applied to the other virtues. By reading stories in which audacious characters either gloriously succeed or nobly fail, readers can internalize this virtue, making it part of themselves.

As a final practical note, I will discuss the teaching of audacity by martial arts instructors. Martin Seligman (2002), a former president of the American Psychological Association, offers advice to parents for the development of character strengths in children. One central piece of his advice for parents to praise children for any displays of positive character traits, a straightforward application of the principles of behavioral psychology to character development. Robert Sternberg (also a former APA president) incorporates group discussions and encouragement of individual reflection in his Teaching for Wisdom Program (Sternberg, 2001). Drawing from these experts on fostering virtuous development, I would pass on this advice to instructors who wish to encourage audacity in students. Talk about the virtue. Incorporate explanations of audacity into training, and occasionally mention its importance during after-hours conversations. Encourage students to read about and reflect upon audacity on their own time. And when you see a student display audacity, praise that student. The verbal reward will encourage the student to continue acting audaciously, and other students will see the praise and be encouraged to develop that virtue themselves.

Conclusion: Balance audatia with the Other Virtues

Cvet (2005) discusses the importance of developing and balancing all four of Liberi’s metaphysical attributes (prudence, speed, courage, and strength). Audacity without prudence leads to recklessness and the possibility of an unnecessary death for a swordsman. Unbalanced strength can result in the fighter being outmaneuvered. I will bring this exploration of audacity to a close by examining some ways in which audacity must be balanced and guided by other virtues if it is to function properly. Due to its enduring popularity among virtue theorists across millennia (Pieper, 1965), I will focus my comments on Plato’s four "cardinal virtues": courage, temperance, justice, and wisdom. As audatia is a subset of courage, I will consider it in balance with the remaining three cardinal virtues in this section.

Temperance is the virtue that protects us from excess, and is often associated with such concepts as self-control and humility (Peterson & Seligman, 2004). Temperance corrects vices such as arrogance, emotional instability, and inability to delay gratification. The guidance of audacity by self-control prevents a daring technique from being sloppy and poorly-directed. Some who focus on the value of reacting "without thought" (perhaps from a simplistic misunderstanding of Zen writings on thoughtless action, or of Hagakure’s passages advocating a "reckless" and "insane" style of fighting) end up flailing uselessly when fighting or sparring. In addition to its function as a hindrance in combat, uncontrolled flailing is also likely to result in overly-bruised sparring partners, as the uncontrolled partner is more likely to strike with an inappropriate degree of force. Unnecessarily hurting one’s fellow students leads to damaged relationships within the training group, the establishment of a poor reputation, the squandering of opportunities for learning, and perhaps an invitation to leave.

In interaction with audacity, humility prevents us from transforming audacious behavior into self-aggrandizing showmanship. A humble display of audacity is one in which the person acting focuses their energy toward the swift accomplishment of their goal without showing off. One possible example in a martial context would be a style of fighting that avoids flamboyant posturing and extravagant flourishes in techniques. Such extraneous actions waste time, waste energy, telegraph moves, and provide unnecessary openings in one’s defense. A humble yet audacious fighter refuses to turn a fight into a show; preferring to act swiftly and decisively to end the confrontation.

Justice within the Aristotelian tradition is derived from the Greek word dikaiosunê. It involves the practice of not violating the order of the universe, and the concept of desert. "To be just is to give each person what each deserves" (MacIntyre, 1984, p. 152). Justice guides audatia by ensuring that our bold actions protect those who need to be protected, harm only those who need to be harmed, and avoid giving protection or harm where they are not deserved. In his Brief Instructions, George Silver (1605) admonishes the gentlemen and brave gallants of England: "Go not into the field with your friend at his entreaty to take his part but first know the manner of the quarrel how justly or unjustly it grew, and do not therein maintain wrong against right, but examine the cause of the controversy, and if there be reason for his rage to lead him to that mortal resolution." A virtuous action is only virtuous if directed toward the proper goal (Pieper, 1965), so an audacious action in the service of injustice is not to be admired.

Fowers (2005) sees practical wisdom as more than simply one virtue among many, but as the key to all virtuous action. Wisdom (phronesis in Greek) allows one to "size up" a specific situation (what Fowers refers to as "moral perception"), see which goal must be pursued, what actions are necessary to achieve that goal, and how best to carry them out. Wisdom and audacity are conceptually linked, as Fowers makes the claim that "moral perception will often result in a clear and immediate response and the appropriate course of action will be immediately apparent" (p. 123). By accelerating one’s ability to correctly judge what to do in a given situation, the cultivation of wisdom thus facilitates audacious behavior.

Wisdom not only permits one to know how best to achieve one’s goals, but also which goals are to be pursued. Wisdom, for example, may also be applied to Silver’s aforementioned admonition not to get involved in unjust quarrels. A reader of this passage in Silver’s treatise might wonder whether or not Silver is recommending abandonment of the virtue of loyalty to one’s friends. Loyalty is clearly a virtue, and other passages from Silver (e.g., "let not one friend upon a word or trifle violate another but let each man zealously embrace friendship") uphold the value of being true to one’s friends. So if a friend is involved in an unjust quarrel, is it better to be loyal, or better to be just? The answer may differ depending on the essential features of the situation. For example, if the friend is severely outnumbered and his life is in danger, the wisest course of action may be to intervene at least so far as is necessary to preserve your friend’s life and extricate him from the situation. You may then feel free to lecture your friend afterward on the virtues of wisdom and justice. If, on the other hand, your friend is only in danger of a well-deserved thumping for his imprudent provocation, it may be wiser to let him learn a moderately painful lesson, and then to lecture him afterward on the virtues of wisdom and justice. This decision may have to be made very rapidly, so wisdom and audacity act together to direct one’s bold actions toward correct goals.

Wisdom also tempers audacity by specifying which situations require boldness and which require patience. Earlier in this essay, I mentioned the balance that must be struck in verbal expressions of audacity. Verbal timidity is not desirable, but neither is obnoxiousness. There is a time to be silent and a time to speak (Ecclesiastes 3:7), and wisdom enables one to know what time it is. One example of this principle in combat might be the common historical assessment that a major factor in the Roman victory over the Celts involves the victory of discipline over ferocity. Herm (1975) describes the "nightmare" experienced by the Roman forces in their battles against the Celts, as the Celtic warriors presented the appearance of chaos itself, attacking with insane fury and reckless daring. What the Celts possessed in passion, though, they lacked in self-control. In the third century BC, at the battle on Cape Telamon, Roman forces learned that screaming hordes of warriors could be defeated by disciplined soldiers forming a tightly-knit wall of shields and sword-points. Wisdom combines with audacity to prevent the improper display of daring, which leads to a self-defeating recklessness (Cvet, 2005).

Audatia, as used by Fiore dei Liberi, refers to a virtue that the author considered central to his art. Audacity is a form of courage that allows for bold and decisive action, overcoming fear and hesitation. Without audacity, the fighter waits, unable to put knowledge into action, and he becomes passive in the fight. By cultivating an audacious combative style, the martial artist is more likely to see victory.

Bibliography

- Cain, A. (2005). Books and becoming good: Demonstrating Aristotle’s theory of moral development in the act of reading. Journal of Moral Education, 34, 171-183.

- Cameron, K. S.; Bright, D.; & Caza, A. (2004). Exploring the relationships between organizational virtuousness and performance. American Behavioral Scientist, 47, 766-790.

- Carr, D. (2005). On the contribution of literature and the arts to the educational cultivation of moral value, feeling and emotion. Journal of Moral Education, 34, 137-151

- Cvet, D. M. (2005). The measure of a master swordsman. Journal of Western Martial Art. Retrieved June 26, 2006 from http://ejmas.com/jwma.

- Dahlsgaard, K.; Peterson, C.; & Seligman, M. (2005). Shared virtue: The convergence of valued human strengths across culture and history. Review of General Psychology, 3, 203-213.

- Darley, J. M.; & Batson, C. D. (1973). From Jerusalem to Jericho: A study of situational and dispositional variables in helping behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 27, 100-108.

- Dueck, A.; & Riemer, K. (2003). Retrieving the virtues in psychotherapy: Thick and thin discourse. American Behavioral Scientist, 47, 427-441.

- Fowers, B. J. (2005). Virtue and psychology: Pursuing excellence in ordinary practices. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Fowers, B. J.; & Tjeltveit, A. C. (2003). Virtue obscured and retrieved: Character, community, and practices in behavioral science. American Behavioral Scientist, 47, 387-394.

- Hamilton, J. B. (1955). Restoration of "the happy warrior." Modern Language Quarterly, 16, 311-324.

- Hatsumi, M.; & Cole, B. (2001). Understand? Good. Play! USA: Bushin Books.

- Hauerwas, S.; & Pinches, C. (1997). Christians among the virtues: Theological conversations with ancient and modern ethics. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press.

- Herm, G. (1975). The Celts. New York: St Martin’s Press.

- Higgins, C. (2003). MacIntyre’s moral theory and the possibility of an aretaic ethics of teaching. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 37, 279-292.

- Kallenberg, B. J. (1997). The master argument of MacIntyre’s After Virtue. In N. Murphy, B. J. Kallenberg, & M. T. Nation (Eds.). Virtues and practices in the Christian tradition: Christian ethics after MacIntyre (p.7-29). Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press.

- Karamyar, H. (2005). The true kendoka disciplines soul and body together. The Iaido Journal. Retrieved June 26, 2006 from http://ejmas.com/tin.

- Kautz, P. (2001). Fiore dei Liberi’s seven rules of wrestling. Journal of Western Martial Art. Retrieved June 26, 2006 from http://ejmas.com/jwma.

- Keen, M. (1984). Chivalry. New Haven, CN: Yale University Press.

- Lee, B. (1975). Tao of jeet kune do. Santa Clarita, CA: Ohara Publications.

- Leming, J. S. (2000). Tell me a story: An evaluation of a literature-based character education programme. Journal of Moral Education, 29, 413-427.

- Lewis, C. T.; & Short, C. (Eds). (1955). A Latin dictionary. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Liddy. G. G. (1980). Will. New York: St Martin’s Press.

- Lovett, R.; Davidson, M.; & Lancaster, M. (Trans.). (2005). Fiore dei Liberi project: Pisani-Dossi representation. Retrieved July 6, 2006 from http://www.the-exiles.org/FioreProject/Project.htm.

- Lowry, D. (1985). Autumn lightning: The education of an American samurai. Boston: Shambhala Publications.

- Lowry, D. (2000). Moving toward stillness. Boston: Tuttle Publishing.

- MacIntyre, A. (1984). After virtue (2nd ed). Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press.

- Maliszewski, M. (1996). Spiritual dimensions of the martial arts. Rutland, VT: Charles E. Tuttle Co.

- Marcinko, R. (1996). Leadership secrets of the rogue warrior. New York: Pocket Books.

- Mohatt, G.; Hazel, K.; & Allen, J. (2004). The people awakening project: Discovering Alaska Native pathways to sobriety. Fairbanks, AK: University of Alaska Fairbanks Psychology Department

- Muraven, M.; Baumeister, R. F.; & Tice, D. M. (1999). Longitudinal improvement of self-regulation through practice: Building self-control strength through repeated exercise. The Journal of Social Psychology, 139. 446-457.

- Murphy, N. (2005). Theological resources for integration. In A. Dueck & C. Lee (Eds), Why psychology needs theology: A radical-reformation perspective (pp 28-52).Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company.

- Musashi, M. (1994). The martial artist’s book of five rings (S. F. Kaufman, Trans.). Boston: Charles E. Tuttle Co. (Original work published 1645)

- Nitobe, I. (1969). Bushido: The soul of Japan. Rutland, VT: Charles E. Tuttle Co. (Original work published 1905)

- Peterson, C. (2006). Follow-up Q & A with Chris Peterson (audio recording). Retrieved June 27, 2006 from http://www.coachingtowardhappiness.com/archive/peterson.htm.

- Peterson, C.; & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Pieper, J. (1965). The four cardinal virtues. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc.

- Price, B. R. (2000). Chivalry and the modern practice of the medieval martial arts. Journal of Western Martial Art. Retrieved June 26, 2006 from http://ejmas.com/jwma.

- Seligman, M. E. P. (2002). Authentic happiness: Using the new positive psychology to realize your potential for lasting fulfillment. New York: Free Press.

- Silver, G. (1599). Paradoxes of defense. Retrieved November 10, 2004 from http://www.aemma.org/silver.htm.

- Silver, G. (1605). Brief instructions to my paradoxes of defense. Retrieved November 10, 2004 from http://www.aemma.org/silver.htm.

- Simpson, D. P. (Ed.). (1977). Cassell’s Latin dictionary. New York: MacMillian Publishing Co.

- Slingerland, E. (2001). Virtue ethics, the Analects, and the problem of commensurability. Journal of Religious Ethics, 29, 97-125.

- Smith, W.; & Hall, T. D. (Eds.). (1871). A copious and critical English-Latin dictionary. New York: American Book Co.

- Spohn, W. C. (1992). The return of virtue ethics. Theological Studies, 53, 60-75.

- Sternberg, R. J. (2001). Why schools should teach for wisdom: The balance theory of wisdom in educational settings. Educational Psychologist, 36, 227-245.

- Sundararajan, L. (2005a, August). Beyond hope: The Chinese Buddhist notion of emptiness. Paper presented at the annual convention of the American Psychological Association, Washington, DC.

- Tsunetomo, Y. (1979). Hagakure: The book of the samurai. (W. S. Wilson, Trans.). New York: Kodansha International. (Original work published 1700)

About the author: is a psychology professor at Redeemer University College in Ancaster, Ontario. He has been a student of the martial arts for over ten years, and is currently affiliated with the Guelph Chapter of the Academy of European Medieval Martial Arts.

Journal of Western Martial Art

September 2006

EJMAS Copyright © 2006 All Rights Reserved