Behind the woodshed:

Little-known aspects of Dussack play through the ages

Journal of Western Martial Art

May 2003

by Christoph Amberger

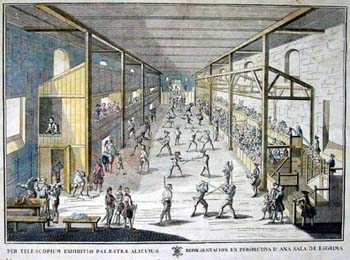

They called it a Dussack, Dusack, Dysack, Tesak, Tuseckn, Thuseckn, Disackn, or Dusägge. And judging from the rather pedestrian taunting rhymes that the staunch craftsmen and artisans of the German fighting guilds made up, it appears that its use was at least as popular as its orthographic variety is mystifying: Some of the 16th-century Fechtschulrheime show that during some 16th-century Fechtschulen, over two thirds of all bouts were fought with the Dussack, by far outstripping those conducted with long swords, staves, and dagger.

Hailed as one of the first true sports fencing weapons by European fencing historians such as Hans Kufahl, Josef Schmied-Kowarzik, and the redoubtable Karl Lochner, this weapon belonged to the standard arsenal of European masters-at-arms from the late 1400s to the early 17th century... when Ulrich Megerle, writing as Abraham a Santa Clara, attributes it as a tool of the Fecht-Narr or Fencing Fool.

The Dussack appears to have replaced the Messer, a long, single-edged cutting weapon similar to the Italian cordelaggio and the falchion, which is depicted in the earliest German sources. Messer with elongated knuckle guards still appear on Vaclav Hajek's 1530s Bible Czech illustrations, as well as in early 16th-century German woodcuts of fighting guild competitions where it is represented at the same place the Dussack would take in later periods.

By the mid 1500s, the Dussack proper had become so popular that you can find depictions of Dussack-wielding pairs of fencers represented in Swiss student Stammbuch albums, on friezes decorating the old city council building (or Rathaus) in Breslau (now Bratislva, Poland)...  and in prints and books published all over the German empire. Even Hans Jakob Christoffel von Grimmelshausen, the author of Germany's national Thirty-Years War epos Der Abenteuerliche Simplicissimus Teutsch, alludes to its international popularity. When his hero is traded to the king of Korea by tartars, he comments:

and in prints and books published all over the German empire. Even Hans Jakob Christoffel von Grimmelshausen, the author of Germany's national Thirty-Years War epos Der Abenteuerliche Simplicissimus Teutsch, alludes to its international popularity. When his hero is traded to the king of Korea by tartars, he comments:

There they valued me because no-one was my equal with the Dusecke.

While martial arts diffusionists might salivate at the prospects of thus having a literary foot in the door that would allow for sweeping assertions about Western broadsword arts imprinting Korean combatives, those among us martial arts historians concerned with establishing historical fact prefer to deal with evidence. Which unfortunately limits us to the written and iconographic sources, most of which originated between the first quarter of the 16th century, and lead us well into the first half of the 18th century.

The Spice of Life

The weapons we find depicted in these sources indicate that there were great morphological differences.

Some illustrations show rather crude instruments, shaped in generous curves, with well-rounded points and a bulbous, featureless thickening toward the hilt... which in many cases consists of a kidney-shaped overture at the center.

Others, like those depicted in Meyer's 1570s magnum opus, indicate elegant, thoughtfully constructed weapons with clipped points, and hilts that are deliberately set off from the "blade" section of the weapon.

Others, like those depicted in Meyer's 1570s magnum opus, indicate elegant, thoughtfully constructed weapons with clipped points, and hilts that are deliberately set off from the "blade" section of the weapon.

Yet others, like one depicted by F. Brun in a print dating back to 1559, have thus far not explicitly analyzed by researchers. Brun's Dussack, for example, placed on the ground in front of an attacking halberd fencer, features a distinct complex hilt. Here, a curved piece of material adds protection to the back of the hand in addition to the integrated knuckle guard of the classic Dussack handle.

Are those differences due to the carelessness of the artists who created the images? Or were there indeed distinct -- maybe regional -- differences in the shape of these weapons?

A hard question to answer with certainty, made even more difficult by the unfortunate circumstance that, despite its popularity, not a single Dussack has survived the ravages of time.

It is the latter fact that actually provides some clues as to what material Dussacken were made of.

Wooden Wonders

The general assumption over the past century and a half was that they were made of wood.

This would make sense: Metal weapons at least those of the cruder hole in a board type would have been extremely unwieldy and murderous in their use. (After all, the purpose of each bout was to draw blood from your opponent's head... and as we shall see later on, some Dussack players certainly made do without any attempt at "finesse"!)

A rare iron Dussack, dated to have been made at the beginning of the 16th century, was found at Nymburg. This weapon, including the elegantly curved knuckle guard, was forged from one piece of metal, with a prolonged and curved blade c. 60cm long and weighing 600g. However, it is the only specimen of its kind not only in (what is now) the Czech Republic, but anywhere in the world. (Interestingly, its dimensions and weight correspond closely to later 18th- and 19th-century heavy cavalry saber models used all over Europe.)Had a larger number of iron Dussacken been in usage, chances are that, given its popularity, a substantial number of them would have survived. Wooden weapons, however, would have fallen victim to the never-ending need for firewood after they were damaged or discarded.

Another material also is mentioned in a Fechtschulrheim dating from August 26, 1573: Benedict Edlbeck, a sieve maker by trade, includes in his list of weapons brought onto the stage that was being prepared for a Fechtschule "ein par Dysackn von Leder gmacht."

However, the stalwart bard does not tell us that these weapons were used in bouting proper, but as a crowd control implement: When the pushing and shoving among the spectators increased to the degree that the actual fencing became impossible, the captain of the Trabanten, a man by the name of Ernst Christoff Zanmacher, took one of the leather Dussacken and jumped among the people, dealing out vicious cuts left and right. He even hit our Meistersinger-narrator Benedict Edlbeck across the back that he "had to stoop".

But apparently, Benedict had no choice but to take the incident in stride: "I rubbed my hips, he did laugh at me."

Red Flowers

Such stoicism in the face of pain could be expected from a fencer whose purpose on the stage was to compete for the "höchst Röhr, und das es blut" ("highest 'Ruhr'" -- from German: (an)rühren, to touch -- "and that it bleeds").

During the Fechtschulen, the public displays of skill where members of the local fighting guilds vied for prize money and "Kräntzlein", injuries like noses split by swords, teeth knocked out by hits into the mouth, eyes gouged out by staff thrusts, even deaths were not uncommon... and how couldn't they, considering the "scoring" mechanism was the "red sweat" pouring out of a head injury.

During the Fechtschulen, the public displays of skill where members of the local fighting guilds vied for prize money and "Kräntzlein", injuries like noses split by swords, teeth knocked out by hits into the mouth, eyes gouged out by staff thrusts, even deaths were not uncommon... and how couldn't they, considering the "scoring" mechanism was the "red sweat" pouring out of a head injury.

Encounters could be drawn-out battles of wits, courage, and skills. Or they could be very short. Like the following:

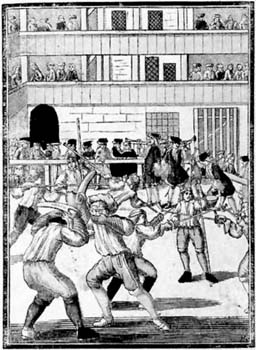

- Fencer Peter Katzengraw, a furrier, is characterized as an "angry" man who nonetheless cuts a dashing figure as he performs the air cuts and moulinets of his Spiegelfechten routine before the match. His opponent is a certain Hans Eisenbeisser, a bold and honest man, "happy, fast, nimble and audacious" who "freely threw the Thuseck all around".

- On the signal of the umpire... probably the lifting of his staff... both opponents straighten and put themselves on guard.

- Katzengraw instantly attacks "with rage" and full force, holding the Dussack with both hands. Of course, he misses, "as one who fences in the wind".

- Eisenbeisser parries, puts aside the attack -- and counters instantly "with hot greed", hitting Katzengraw on the head that the blood runs freely. Eisenbeisser recognizes his victory, and jumps about on the battleground, since he "not only won the fame but the prize money as well."

It appears as valid hits could be scored both by cuts and by thrusts: One of the few Federfechters injured during a Nürnberg Fechtschule that took place on May 10 of the same year received an Ortt or point thrust. The fact that the recording poet found this worth mentioning might indicate that the Ortt was considered a disreputable move (as the typical pre-amble to the beginning of Fechtschul bouting expressly stipulated)... but that the injured man was still regarded as defeated by virtue of the bleeding head injury.

Protecting the Goods

While most of the Dussack images from the 16th and 17th century depict fencers wearing what would amount to their street clothes, other sources indicate that, there was indeed a certain degree of protective gear involved at the Fechtschul Dussack displays.

The Eschenbach Federfechter Hanns Schuler mentions "dicke Wammeser" -- thick jerkins -- as being worn by both Marxbrüder and Federfechter. On occasion, one guild would challenge the other to up the ante and cross wood in a more scantily clad fashion. The refusal to put the plastrons aside and fence without, however, could result in "not much fencing going on"

Lower arm protection can be documented as early as the 1530s. A German painted glass fragment -- made accessible to the research community during the exhibition "Die Fechtkunst 1500-1900, Grafik und Waffen" at the Veste Coburg from June 1-September 15, 1968 -- depicts one fencer wearing what appears to be a harness of riveted or interwoven leather straps on his lower arm. By the early 1700s, Dussack fencers appear to be wearing heavily padded cuffs that reach up to the elbow, and even beyond. In fact, they have begun to wear padded cuffs on both arms and are using the raised left arm defensively to shield themselves from hits to the head and face.

(We see a similar phenomenon in rural English singlestick systems, where the unarmed hand grasps a handkerchief that has been tied around the thigh... and allows the fencer to anchor his grip as he uses his lower arm, elbow pointing up, to deflect incoming flicks to the face and head.)

At this late point in the Dussack's development, the head is protected by a turban-like cap or wrap. (Judging by the dejected expression of a defeated Dussack player, the protection it afforded may have been partial. But it bears pointing out that in the early 18th-century copper both figures are taken from, Dussack players appear to be the only ones wearing the specialized head gear.

Systematic Change

Throughout fencing history, radical changes in technique and purpose of any given subsystem are frequently signaled by accelerated change and development in the gear associated with the system.

For the Dussack, the incremental addition of protective gear occurs only decades before the system disappears from the record. After the 1730s, few if any sources mention its systematic use again.

For the Dussack, the incremental addition of protective gear occurs only decades before the system disappears from the record. After the 1730s, few if any sources mention its systematic use again.

Some of its peripheral characteristics survive in related systems, however. A padded arm that could be used to block incoming hits would become a defensive mainstay of Central European Schlägerplay, which also carries on the cohesiveness of a sequentially patterned "aus dem Bogen schlagen" as postulated by Meyer in 1570. The höchste Ruhr and Rote Plume of the Fechtschulen also find their sanguine continuation in the Anschiß; or First Blood rules of the 19th-century duelling students.

Even the defensive use of the second arm (albeit without additional padding) can be followed on its parallel course throughout the 18th and 19th century throughout German fencing traditions... most pronouncedly in the Kreusslerian thrust system as codified by Anton Friedrich Kahn and, later, by F.A.W. Roux and his successors and protégés at the Verein Deutscher Fechtmeister.

But except for a few scattered examples, staff, long sword, and Dussack traditions disappear from the Central European fencing scene before the 18th century is half over. And except for a short-lived revival at the University of Vienna in the 1880s, it has taken until the beginning of the 21st century to rekindle an interest in their practical reconstruction.

Hammerterz Forum Collected is available for purchase. It is a 8x10 inches, and cerlox bound manuscript. It is 364 pages covering the Summer of 1994 to the Fall of 1999, the complete print run. Click "here" for more details.

About the author: Born in 1963, grew up in what used to be West Berlin, Germany. He studied Latin, English, history, dentistry, Gaelic,

English and American Literature, journalism, philosophy, and economics with varying degrees of devotion and perseverance at the Freie Universität Berlin, the University of Aberdeen in Scotland, and the Georg-August-Universität Göttingen before obtaining his Master of Arts at St. John's Graduate Institute in Annapolis, Maryland. He has been living in the United States since 1989, is married and has three children.

English and American Literature, journalism, philosophy, and economics with varying degrees of devotion and perseverance at the Freie Universität Berlin, the University of Aberdeen in Scotland, and the Georg-August-Universität Göttingen before obtaining his Master of Arts at St. John's Graduate Institute in Annapolis, Maryland. He has been living in the United States since 1989, is married and has three children.

A regular contributor to American Fencing, the magazine of the United States Fencing Association, and to the British fencing magazine The Sword, as well as the German Einst und Jetzt, he founded Hammerterz Forum in 1994. He has been featured in the Discovery Channel's 1997 documentary series Deadly Duels, has been a consultant to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York for the exhibition The Academy of the Sword, and is considered one of the foremost experts on historical edged-weapons combat in the United States.

As a member of two of the most respected duelling fraternities in Germany, he fought seven Mensuren with the bell-guard and basket-hilt Schläger between 1985 and 1987 and acted as a second in 25 more. His weapon of choice on the sports fencing strip is the saber.

Journal of Western Martial Art

May 2003

EJMAS Copyright © 2003 All Rights Reserved