SEVERAL REMARKS ON THE

BLOßECHTEN SECTION OF CODEX WALLERSTEIN

Journal of Western Martial Art

April 2001

by Grzegorz Zabiñski

1.0 Abstract

The paper deals with selected aspects of Bloßfechten (unarmoured combat)

with the longsword as depicted in one of the most renowned, yet still unpublished

source of medieval swordsmanship known as Codex

Wallerstein (Universitaetsbibliothek

Augsburg, I. 6.4°.2). Firstly, the author deals with the very structure

of the manuscripts, proving that it actually consists of two different

manuals (the one from late fourteenth-early fifteenth century, the other

from about mid-fifteenth century, which were later put together). Furthermore,

the question of the way in which the section under analysis was accomplished

is discussed: it is suggested that the images were put in first, and then

provided with relevant comments. Next, the author attempts classifying

the weapon presented in the section by means of comparing it to a well-known

and commonly accepted typology of Robert E. Oakeshott. Moreover, several

remarks concerning the functionality of such particular types of weapon

are introduced. Furthermore, the author deals with several general fighting

principles as presented in the manuscript, trying to affiliate them to

the school of German swordsmaster Johannes Liechtenauer; however, he notices

several similarities to other fencing manuals, with special regard to that

of Fiore dei Liberi. Then, the comments concerning particular plates and

fighting actions presented on them are provided. Next, the author attempts

to show several similarities between the actions presented and those depicted

in other medieval fencing manuals. Finally, conclusions and suggestions

for further research (comprising in the first instance the necessity of

a critical edition of the manuscript) are provided.

2.0 Introduction

The

aim of this paper is to comment on the unarmoured long sword fighting as

presented in one of the best known late medieval Fechtbuch, the

Codex Wallerstein. The manuscript containing this manual is preserved in

the collection of the Universitätsbibliothek Augsburg (I.6.4?.2). The codex

is a paper quarto manuscript, written in Middle High German, containing

221 pages (108 numbered charts, and several unnumbered ones at the beginning),

numbered every odd one in the upper right corner, starting from page 4

which is given No. 1. Page 1 contains a date 1549, a name of one of the

manual's owners,Vonn

Baumans, and the word Fechtbuch, while pages 2 and 3 are blank.

This manual seems to consist of two different Fechtbücher (for the

sake of convenience called further A and B), which were put together and

later given a common pagination.

Part A (No. 1 recto-No. 75 recto, and No. 108 verso; thus consisting of

151 pages) is probably from the second half of the fifteenth century, on

account of both the representations of arms and armour on No. 1 verso (full

plate armours and armets) and No. 2 recto, andthe

details of costumes on No. 108 verso.

On the other hand, part B (No. 76 recto-No. 108 recto; 66 pages) is probably

of much earlier origin, which, on account of the details of armour (bascinets

without visors or bascinets with early types of visors; mail hauberks;

garments worn on the cuirasses) can be dated to late fourteenth-early fifteenth

century.

numbered every odd one in the upper right corner, starting from page 4

which is given No. 1. Page 1 contains a date 1549, a name of one of the

manual's owners,Vonn

Baumans, and the word Fechtbuch, while pages 2 and 3 are blank.

This manual seems to consist of two different Fechtbücher (for the

sake of convenience called further A and B), which were put together and

later given a common pagination.

Part A (No. 1 recto-No. 75 recto, and No. 108 verso; thus consisting of

151 pages) is probably from the second half of the fifteenth century, on

account of both the representations of arms and armour on No. 1 verso (full

plate armours and armets) and No. 2 recto, andthe

details of costumes on No. 108 verso.

On the other hand, part B (No. 76 recto-No. 108 recto; 66 pages) is probably

of much earlier origin, which, on account of the details of armour (bascinets

without visors or bascinets with early types of visors; mail hauberks;

garments worn on the cuirasses) can be dated to late fourteenth-early fifteenth

century.

As mentioned, it is difficult to deal extensively with the history of

the codex without having the real manuscript at one's disposal-anyway,

it is not the purpose of this contribution. However, it is worth noticing

that this Fechtbuch belonged once to one of the most famous sixteenth-century

authors of combat manuals, Paulus Hector Mair;

and it was he who was the author of the contents of the manuscript (No.

109 recto), and several minor remarks on the number of pages for particular

sections of the manual, which were inserted on some places in the codex.

Codex Wallerstein, like many other medieval and Renaissance Fechtbücher,

contains a wide range of sections devoted to particular weapons and kinds

of fighting: part A comprises sections on long sword (Bloßechten),

wrestling (Ringen), dagger (Degen), and falchion (Meßer),

and consists of images provided with relevant comments. On the other hand,

part B-comprising the long sword Bloßechten, Harneschfechten

'armoured combat' with long swords, long swords together with shields,

lances and daggers, judicial shields and swords, judicial shields and maces,

unarmoured wrestling-consists of images only, without any comments or explanations.

This manual, as many other fighting manuals,

puts considerable streß on judicial duels, which is certified by several

elements typical for such kind of fighting. For example, No. 1 verso and

No. 2 recto,present

a remarkable scene of a duel on a fenced yard, with coffins already prepared

for both combatants; moreover (apart from such obvious elements like judicial

shields and maces), one's attention is drawn by the crosses on the garments

of combatants in part B.

The distribution of sections devoted to particular kinds of combat in

part A is very uneven: the most prominent place is held by unarmoured wresting

(No.15 recto-No.20 verso, and No.33 recto-No. 74 recto: 94 pages), followed

by unarmoured long sword combat (No.3 recto-No 14 verso, and No.21 recto-No.21

verso: 26 pages), unarmoured dagger combat (No. 22 recto-No.28 verso: 14

pages), and finally, unarmoured falchion combat (No. 29 recto-No. 32 verso:

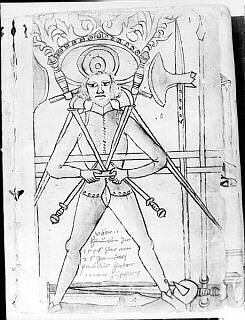

8 pages). Apart from that, section A contains an image of a man-at-arms

(No. 1 recto), the scene of a judicial duel (No. 1 verso-No.2 recto), a

rather ridiculous piece of advice on how to kill a peasant with a knife

(No.74 verso), and the depiction of four persons in courtly costumes (No.

108 verso).

Although such presentation of the material is not a peculiarity of this

manuscript (another example could be Talhoffer's Fechtbuch aus dem Jahre

1467, where, for example, comments on long sword unarmoured combat

are divided into two sections),

the fact that sections on particular weapons are mixed with one another

to such extent makes the researcher wonder about the way in which the manuscript

was actually written. It could be tentatively suggested that the scribe

proceeded gradually, writing or copying particular sections as he had acceß

to relevant data, without caring about putting the material in a coherent

order. Moreover, the scribe of part A was in all probability not very familiar

with the Kunst des Fechtens. To support this point of view, one

can refer to No. 9 verso and No. 10 recto, when the scribe simply confused

the comments to two images with each other-at least, he realized his mistake

and provided the images with relevant explanations. On the other hand,

it could be supposed that the manuscript was first illustrated, and then

provided with comments; however, the fact that the scribe confused the

comments for two entirely different techniques speaks a lot about his knowledge

of the subject.

Of interest is the fact that in the first seven plates of the long sword

section (No. 3 recto-No. 6 recto) there are headings with general fighting

principles:

written just above the first line of the comments, and with a different

script, they are in all probability later additions.

The aim of this contribution is to present brief remarks on the long

sword section of part A of the manuscript: for the audience's convenience,

the relevant pages will be referred to from now on by single numerals,

without the use of recto-verso division. Thus, the numeration will be as

follows:

-No.

1 recto: plate 1,

-No.

1 verso: plate 2,

-No.

2 recto: plate 3,

-No.

2 verso: plate 4,

-No.

3 recto: plate 5,

-No.

3 verso: plate 6,

-No.

4 recto: plate 7,

-No.

4 verso: plate 8,

-No.

5 recto: plate 9,

-No.

5 verso: plate 10,

-No.

6 recto: plate 11,

-No.

6 verso: plate 12,

-No.

7 recto: plate 13,

-No.

7 verso: plate 14,

-No.

8 recto: plate 15,

-No.

8 verso: plate 16,

-No.

9 recto: plate 17,

-No.

9 verso: plate 18,

-No.

10 recto: plate 19,

-No.

10 verso: plate 20,

-No.

11 recto: plate 21,

-No.

11 verso: plate 22,

-No.

12 recto: plate 23,

-No.

12 verso: plate 24,

-No.

13 recto: plate 25,

-No.

13 verso: plate 26,

-No.

14 recto: plate 27,

-No.

14 verso: plate 28,

-No.

21 recto: plate 41

-No.

21 verso: plate 42.

3. The longswords in part A of Codex Wallerstein

With regard to the length of the long swords in section A, they seem to

vary considerably: from about 110-120 cm (plates 5, 6, 7, 8, 20, 24, 25,

26, and 41), through about 130-140 cm (plates 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17,

18, 19, 22, 23, 24, 27, 28, and 42) to about 150 cm (plates 9, 10, and

21), or even 160-180 cm (plates 1, 2, and 3); similarly, the lengths of

the hilts vary. However, this variety seems to have been caused rather

by the illuminator's style (it is a well-known fact that medieval artists

often did not pay much attention to issues of dimensions and proportion)

than by a conscious differentiation for the purpose of particular techniques.

What is important is the fact that all the long swords can be seen as belonging

to one type: ridged blades without fullers, with a diamond-shaped cross-sections,

and rigid, sharp points; fig-shaped pommels; simple straight cross-pieces

with chappes. According to the commonly accepted typology of Robert E.

Oakeshott, the blades could be classified as type XV or XVIII (the difference

consist in the fact that a blade type XV has a ridge flanked with deeply

hollowed faces, in the case of type XVIII the ridge rises from almost flat

faces): it does not seem possible to solve this issue by looking at the

images in the manuscript. Actually, one would rather opt for type XVIII,

as type XV (which dates back to the thirteenth century) is in the fifteenth

century accompanied by a short, one-handed grip. However, it may not be

that important, as both types of blades were so similar to each other in

the fifteenth century that it is sometimes hard to distinguish them from

each other.

As regards the cross-pieces, they belong clearly to type 1;

the pommels represent the T family and bear the strongest resemblance to

the T3 type (plates 1, 2, 3, 15, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 25, 26, 27,

28, 41, and 42).

Of course, one could ask the question whether the codex illuminator

had a particular type of sword in front of his eyes when illustrating the

manuscript, or he was rather presenting in general the forms of sword commonly

used in his environment: the latter option is more probable. Moreover,

one should not assume that he was that much interested in depicting the

details of weapons which were surely well known to contemporary men. Therefore,

the above attempt at classifying the swords should be rather seen as a

search for analogies among the known examples of existing artifacts than

as a decisive definition of the weapon's typology.

A functional analysis of the swords presented in the manuscript is more

important: this shape of the blade was universal both for cutting and thrusting,

and the form of pommels allowed a comfortable operation with both hands-that

was especially relevant for the purpose of winding (e.g., plates 6 or 8),

and generally the techniques performedwith

crossed forearms (e.g., plates 7, 9, 10 or 13), as well as hitting with

the pommel (e.g., plates 22 or 25).

4. General fighting principles

Like many other manuals, the Codex Wallerstein long sword section does

not cover all the aspects of swordsmanship,

for example, it has been rightly noticed that there is no mention about

Meisterhau

'master

cuts'.

On the contrary, it seems to focus on some selected problems, to mention

the most important ones, like:

-

Binden an das Schwert (binding on the sword)

and possible actions from that (plates 5, 6, 7, to a degree plate 8, where

binding is not the point of departure, but one of consequent elements of

action; 9, 10 (a situation similar to 8), 11, 12, 13, to a degree also

plates 14, 15, 16, which are put as a sort of outcoming options from the

action presented in plate 13;moreover,

plates 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 41, 42). As one can see,

almost the entire section covers the problem of binding, which could suggest

that it was copied from a relevant part of another manual. Obviously, one

of most natural and recommended actions from Binden are Winden

(winding) techniques (of particular interest is that here they are mostly

performed with the short edge) which are presented on following plates

concerning Binden: 6, 7 (here winding is used not to hit the opponent

but to push his blade aside), 8, 10, 11, 12, 13, 15 (referred to as Außerwinn

'Outerwinding'), 19, 20, 21, 22, 24, 28.

-

Schwertsnehmen (taking the adversary's sword): in general, these

techniques result here either from binding (plates 22, 23, 25, 26, 27,

42) or from other actions, like supposedly a missed thrust (plate 17).

-

Gewappnete Hand (half-sword) techniques: resulting from binding,

these techniques occur either in form of Legen (placing the blade

at the adversary's neck), followed either by a slicing cut or a throw (plates

19, 20, 26) or Stoßen (thrusting) (plates 6, 21, 28).

-

Werffen(throwing or armlocks) techniques,

performed usually, although not always, with the help of the blade (plates

8, 11, 18, 19, 20, 27 and 41).

-

Leng and Masse (length and reach, referring to proper distance

and stance), as in plates 5 and 6.

Moreover, one is able to discern some fighting principles which were typical

for the "school" of swordsmanship based on Johannes Liechtenauer's teaching,

for example:

-

Schwach/Sterck (weak/strong), like in plates 7 and 8.

-

issue of timing (Vor/Nach/Inndes-'before', 'after', 'simultaneously'),as

in plates9, 10, 11, 19 and 22.

-

Mention of Bloßn (openings)-plate 7.

-

überlauffen (overrunning, here presented as dringe in ihn

'run in him')-plate 9 and probably 10.

With regard to the issue of guards, one can see several of these which

were used in the "school" of Liechtenauer, like Pflug (middle guard-it

is definitely the most common one in this section of the manuscript), depicted

on plates 5, 6, 22, 25, 26; moreover (not directly, but it was surely a

position of departure here) on plates 7, 11, 13, 14, 15, 16, 18, 19, 20,

21, 23, 24, 28, 41; Hengort or Langort (hanging point or

long point) on plates 8, 14, 42; Ochs (hanging guard) on plates

9, 10, 11, 13, 27 (with a splendid example of hanging guard binding). The

issue of interest is definitely the stance of the scale (Waage),

known rather from wresting than swordfighting

on plates 5 and 12-on the other hand, one could assume that this principle

refers rather to a principle of balanced legs and body position.

The question of interest, which has provoked a debate among the fencing

audience, is definitely the problem of edge-parrying.

Although the phrase versecz mit der kurczen sneid (deflect with

the short edge) appears in the section (plates 9, and 10), instead it should

beunderstood as deflecting done

on the opponent's flat performed with one's own edge, although one cannot

exclude an accidental edge-to-edge contact there.

5. Particular actions

Having dealt with selected general principles of swordsmanship, one has

to consider particular fighting actions individually. Both due to the scarcity

of space and on account of the fact that the author works at present on

the edition of Codex Wallerstein (Volume 1 should appear at the end of

this year), there would be no point in presenting the whole text of the

transcription. Instead of that, short comments based on the original text

are provided. As, due to copyright restrictions imposed by the source university, it was not possible to insert

the images into the present page, relevant images from the website of the Academy of European Medieval Martial Arts are accessible through registering for an online library security pass.

-

Plate

1 A presentation of the angles of cutting.

-

Plate

2 A scene of a judicial duel.

-

Plate

3 A scene of a judicial duel.

-

Plate

5 The length principle: swordsmen are advised to stretch their

arms and their swords far from them, and put themselves into a low body

position with knees bent, which should secure them with a long reach, and

the chance at efficiently responding to the necessities of combat.

-

Plate

6 The reach principle: having his sword bound by his adversary,

the swordsman on the left is advised to wind in his opponent's face with

his short edge, so that he could either hit him with the pommel or thrust

at him at the half-sword.

-

Plate

7 The 'weak' principle: binding his opponent on the sword, the

swordsman on the right is advised to check whether the adversary is "soft"

or "tough": if he is "tough", he should wind in his face as before; if

he is "soft", he should find the weak part of his sword, and wind it to

his left, so that he could hit his head or find the openings.

-

Plate

8 The 'strong' principle: the swordsman on the left strikes an

Oberhau

at his adversary: if the latter parries the stroke, the attacker is advised

to find the weak part of the defender's sword and bind it with his cross-piece,

so that he could place his short edge on his neck and throw him on the

ground.

-

Plate

9 The 'before' principle: binding his opponent, the swordsman on

the left must defend his head from his adversary: he is advised to deflect

the stroke with his short edge and rush in at the opponent to make him

strike again-if the adversary strikes from the other side, it should be

countered by putting the sword on his shoulder to his ear.

-

Plate

10 The 'after' principle: the swordsman on the left is being threatened

with his adversary's Oberhau: he is advised to deflect the stroke

with his short edge. If the opponent delivers another stroke, the swordsman

on the left should hit his sword with his short edge in order to bind his

adversary's sword and hit the back of his head.

-

Plate

11 The 'simultaneously' principle: if the opponent binds the swordsman

on the left on his sword and tries to wind in his face or perform another

action, the swordsman is advised to counter-wind simultaneously, hit his

arms strongly and push him back to throw him on the ground.

-

Plate

12 The swordsman on the left binds his adversary, who winds him

in his face: the swordsman on the left is advised to counter-wind and hold

his opponent's sword on his cross-piece to prevent him from passing in

front of his sword and doing any further action.

-

Plate

13 The swordsman on the right binds his adversary on the sword,

and the opponent tries to wind in his face: the swordsman on the right

is advised to counter-wind in order to push his opponent's sword up, and

then to deliver a twisted stroke (Verzuckter Schlag) in his elbow.

-

Plate

14 A continuation of plate 13: if the opponent parries the stroke,

the swordsman on the right is advised to hit his opponent's sword downwards

with his pommel and then to put his own short edge on the opponent's neck

in order to deliver a slicing cut.

-

Plate

15 A continuation of plate 13: it the opponent parries the stroke,

the swordsman on the right is advised to hold his sword on the adversary's

blade, and together with a step forwards with his right foot, to strike

at the opponent's left arm.

-

Plate

16 A continuation of plate 13: if the opponent parries the stroke,

the swordsman (now depicted on the left) is advised to hit with his left

hand in his adversary's arms, and, having stabbed with his sword between

himself and his opponent's sword, to place his blade on his adversary's

neck in order to break his arm and deliver a slicing cut against his neck.

nbsp;

-

Plate

17 If the sword of the swordsman on the left was grasped under

his adversary's left arm, who wants to deliver a stroke or a thrust, the

swordsman on theleft is advised to thrust forward with his sword and, having

grasped his own blade with his left hand, to apply an armlock in order

to break his opponent's arm.

-

Plate

18 A continuation of plate 16: if the adversary attempted hitting

the swordsman on the left in his elbow and the latter parried the stroke,

and then the opponent tries to stab between himself and the blade of the

swordsman on the left in order to hit his neck, the swordsman on the left

is advised to grasp the opponent's blade in his left hand and to put it

on his neck in order to throw him on the ground.

-

Plate

19 If the swordsman on the left is bound on the sword by his adversary,

he is advised to wind with his short edge in his face, and to go simultaneously

forward with his left foot, to hit the opponent's arms with his pommel,

and, having grasped his own blade with his left hand, to place it at the

adversary's neck in order to throw him on the ground.

-

Plate

20 The adversary binds the swordsman on the left on the sword and

winds him in his face: the swordsman on the left is advised to counter-wind

and hit the opponent's arms with his pommel as above, and then to place

his sword on his adversary's neck or head in order to throw him on the

ground.

-

Plate

21 If the opponent tries to wind the swordsman on the left in his

face, the latter is advised to grasp his blade with his left hand and to

thrust above his adversary's blade into his testicles.

-

Plate

22 If the swordsman on the left is bound on the sword by his opponent,

he is advised to wind with his short edge and rush simultaneously in him,

and then to grasp his hilt between his hands with his own left hand, and

to hit his face with the pommel in order to take his sword away.

-

Plate

23 If the swordsman on the left is bound on the sword by his adversary,

who wants to wind him in his face, the former is advised to grasp both

blades with his left hand, and to pull them towards his left; then, he

should go against his opponent's hand and hit from under through it, in

order to take his adversary's sword away.

-

Plate

24 The opponent binds the swordsman on the left on the sword, and

wants to wind or thrust at him; the swordsman on the left is advised to

counter-wind and, having placed his short edge on the opponent's sword,

to wind his adversary's blade powerfully so that he turns, in order to

hit his head.

-

Plate

25 If the swordsman on the left is bound on the sword by his adversary,

he is advised to hit his opponent's hilt with his right hand between his

adversary's hands, pull it towards himself,then

to push it aside with the cross-piece and to hit his opponent's face with

his pommel.

-

Plate

26 If the opponent binds the swordsman on the left on the sword

and wants to wind in his face, the latter is advised to raise his sword,

and to hit between his adversary's hands with his pommel, and, having grasped

his own blade with his left hand, to wind in his opponent's head.

-

Plate

27 If the swordsman on the left is bound on the sword by his adversary

in the hanging guards, he is advised to grasp the opponent's hilt with

his left hand above the right arm of his opponent, and then to pull

backwards.

-

Plate

28 If the adversary binds the swordsman on the left on the sword,

the latter is advised to wind and hit the opponent from above with his

pommel; then, he should grasp his blade with his left hand, and treating

with his left foot behind his adversary, he is advised to deliver a slicing

cut to the opponent's neck and to stab him.

-

Plate

41 If the swordsman on the left is bound on the sword by his opponent,

he is advised to pretend as if he wanted to wind in his opponent's face;

then, he should hit his adversary's sword with his cross-piece, and letting

his own sword fall above his head, he should hit him from under in his

legs in order to throw him on the ground.

-

Plate

42 If the adversary binds the swordsman on the left on the sword,

the latter is advised to grasp both blades with his left hand and to go

with his pommel under his opponent's sword and to pull backwards in order

to take awayhis sword.

6. Analogies and similarities

On one hand, it is extremely tempting to search for analogies from other

fencing manuals in order to establish potential sources and a tentative

provenence of the manuscript; on the other hand, it is a truism to say

that writing was by no means a chief way of spreadingswordsmanship-on

the contrary, it was done by means of personal contacts with available

masters and their skills. Moreover, it is to be borne in mind that the

fact that similar or even identical actions are presented in two different

manuals does not necessarily mean that they are interrelated: it is a well-known

feature of the martial arts that different schools and systems may independently

find similar solutions to similar problems. However, in order to see these

similarities, an attempt at finding relevant fencing actions from some

other well-known manuals was undertaken. For the purpose of comparison,

the following manuals available to the author were applied: Das Solothurner

Fechtbuch, the famous manual by Fiore dei Liberi Flos Duellatorum,

as well as the Fechtbuch by Hans Talhoffer from 1467. With regard

to these manuals, the parallels are the following:

-

plate 1: similar figure appears in dei Liberi (chart 17a, page 151),

demonstrating the angles of attack.[22]

-

plate 8: one may search for analogies to Das Solothurner Fechtbuch,

plate 77, where the swordsman on the left seems to cut into his opponent's

neck with his short edge; however, in the case of this manual the matter

is aggravated by the fact that it was not provided with relevant comments

and one has to rely on the editor's interpretation.[23]

-

plate 9: a similar action is presented in Das Solothurner Fechtbuch,

plate 84.[24]

-

plate 16: a certain degree of similarity may be seen in dei Liberi

(chart 20b, page 158, bottom right), although in that case the point of

departure of this action is unknown; the same may be said about chart 22a,

page 161, top right.

-

plate 17: an obvious analogy is depicted in dei Liberi (chart 23b,

page 164, bottom right).

-

plate 19: similar action is presented in dei Liberi (chart 21a,

page 159, bottom right). Although with a different point of departure (binding

the swords in a low guard) and a different intention (to cut into the opponent's

face); moreover, the way of holding the opponent's sword is slightly different

(hooking the adversary's right arm). Moreover, there is an analogy to Talhoffer

(plate 24), although the comment there is not very informative.[25]

-

plate 21: a similar thrust is depicted in Talhoffer (plate 36),

although with a different point of departure (hanging guard in its version

of squinting guard), and a different intention (thrusting into the adversary's

throat).

-

plate 22: the principle of grasping the opponent's sword and hitting

his face with the pommel appears in dei Liberi, although with different

way of grasping (catching the opponent's right arm, chart 22a, page 161,

bottom left; grasping the opponent's left arm from above, hitting between

the adversary's hands or grasping his pommel from under, chart 24a, page

165, top right, bottom left and right).

-

plate 26: similar action is depicted in dei Liberi (chart 21a, page

159, bottom right), although with differences mentioned for plate 19.

-

plate 27: a similar way of grasping the adversary's hilt above his

right arm is depicted in Das Solothurner Fechtbuch, plate 90). However,

this action is performed from middle guard.[26]

-

plate 41: a throw of the adversary while holding his legs is depicted

in Talhoffer (plate 34), although with a different point of departure (as

a defense against a stroke).

As it can be seen from the above comments, the Bloßechten section

in Codex Wallerstein bears several similarities to other swordsmanship

manuals, with special regard to that by Fiore dei Liberi;[27]

however, it cannot be determined here whether it was caused by a direct

influence of this work, mutual contacts and analogies between German and

Italian swordsmanship, or by merely solving similar problems in a similar

manner.

Suggestions for further research

The first postulate from the remarks presented in this contribution is

surely the publication of Codex Wallerstein-the author works at present

on a critical edition of this manuscript, whose first volume should appear

at the end of 2001.

Furthermore, it is of high interest to search for analogies to other

fencing manuals of that period, which would not only bring answers to the

questions related directly to this manuscript, but would deepen in general

the knowledge of medieval swordsmanship. With regard to the very manuscript,

one should attempt to determine the existence of any governing principles

common for various parts of it (the presence of Waage position both

in section on long sword and wrestling was already mentioned), which would

potentially connect them into a coherent fighting system.

Finally, a practical analysis of particular fighting actions should

be carried out in order to check their real applicability for the purposes

of combat-to a degree, such analysis was carried out by the author (here

he would like to expreß his gratefulneß to his friends Bartłomiej Walczak

and Rußell Mitchell for their cooperation and valuable comments), but

it surely did not fully explore all of their possible implications.

Bibliography

- Anglo, Sydney. The Martial Arts of Renaissance Europe. New Haven and London: Yale University Preß, 2000.

- Clements, John. Medieval Swordsmanship: Illustrated Methods and Techniques. Boulder: Paladin Preß, 1998.

- Codex Wallerstein. Universitätsbibliothek Augsburg, Cod. I. 6. 4°.2 Available on the webpage of The Historical Armed Combat association (http://www.thehaca.com/pdf/CodexW.htm); and The Academy of European Medieval Martial Arts (http://www.aemma.org/library.htm)

- Das Solothurner Fechtbuch (1423). Edited by Charles Studer. Solothurn: Vogt-Schild AG. Available on the webpage of the Historical Armed Combatassociation (http://www.thehaca.com/pdf/Solothurner.htm)

- dei Liberi da Premariacco, Fiore. Flos duellatorum in armis, sine armis, equester, pedester. Edited by Franceso Novati. Bergamo: Instituto Italiano d'Arti Grafiche, 1902. Also available on the webpage of The Academy of European Medieval Martial Arts (http://www.aemma.org/liberi.htm); and The Historical Armed Combat association (http://www.thehaca.com/pdf/Liberi.htm)

- Dörnhöffer, Friedrich. "Quellen zur Geschichte der Kaiserlichen Haußammlungen und der Kunstbestrebungen des Allerdurchlauchtigsten Erzhauses: Albrecht Dürers Fechtbuch." Jahrbuch der Kunsthistorischen Sammlungen des Allerhöchstes Kaiserhauses 27.6 (1909): I-LXXXI. Available on the webpage of The Academy of European Medieval Martial Arts (http://www.aemma.org/library.htm).

- Edge, David, and John Miles Paddock, Arms and Armor of the Medieval Knight: An Illustrated History of Weaponry in the Middle Ages.New York: Crescent Books, 1991.

- Hils, Hans-Peter. "Hans Talhoffer: Fechtbuch." In Wertvolle Handschriften und Einbände aus der ehemaligen Oettingen-Wallersteinschen Bibliothek. Edited by Rudolf Frankenberger, and Paul Berthold Rupp, 96-98. Wiesbaden: Reichert Verlag, 1987.

- Hils, Hans-Peter. Meister Johann Liechtenauers Kunst des langen Schwertes. Europäische Hochschulschriften 3. Geschichte und ihre Hilfswissenschaften 257. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 1985.

- Houston, Mary G. Medieval Costume in England and France: the 13th, 14th, and 15th Centuries. New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1996.

- Oakeshott, Robert E. The Archaeology of Weapons. Boydell Preß, 1964.

- Talhoffer, Hans.Fechtbuch aus dem Jahre 1467. Edited by Gustav Hergsell. Prague: J.G. Calve'sche K.K. Hof-und Universitäts-Buchhandlung, Ottomar Beyer, 1887. Available on the webpage of The Academy of European Medieval Martial Arts (http://www.aemma.org/library.htm); and The Historical Armed Combat association (http://www.thehaca.com/pdf/Talhoffer1443-1459Editions.htm).

- Talhoffer, Hans. Fechtbuch aus dem Jahre 1443. Edited by Gustav Hergsell. Prague: Selbstverlag, 1889. Available on the webpage of The Historical Armed Combat association (http://www.thehaca.com/pdf/Talhoffer1443-1459Editions.htm).

- Talhoffer, Hans. Fechtbuch aus dem Jahre 1459. Edited by Gustav Hergsell. Prague: Selbstverlag, 1889. Available on the webpage of The Academy of European Medieval Martial Arts (http://www.aemma.org/library.htm); and The Historical Armed Combat association (http://www.thehaca.com/pdf/Talhoffer1443-1459Editions.htm).

- Talhoffer, Hans. Medieval Combat: A Fifteenth Century Illustrated Manual of Swordfighting and Close-Quarter Combat. Translated and Edited by Mark Rector. London: Greenhill Books, 2000. Available onthe webpage of The Historical Armed Combat association (http://www.thehaca.com/talhoffer.htm)

- Wierschin, Martin. Meister Johann Liechtenauers Kunst des Fechtens. Münchener Texte und Untersuchungen zur Deutschen Literatur des Mittelalters. Kommission für Deutsche Literatur des Mittelalters der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften 13. C.H. Beck'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, München 1965.

For example, see Hans Talhoffer, Fechtbuch aus dem Jahre 1467. Edited

by Gustav Hergsell (Prague: J.G. Calve'sche K.K. Hof-und Universitäts-Buchhandlung,

Ottomar Beyer, 1887). A modern English edition which is used here: Medieval

Combat: A Fifteenth Century Illustrated Manual of Swordfighting and Close-Quarter

Combat. Translated and Edited by Mark Rector (London: Greenhill Books,

2000); Judicial duels are also dealt with in other manuals of Talhoffer:

Fechtbuch

aus dem Jahre 1443.Edited

by Gustav Hergsell (Prague: Selbstverlag, 1889), and Fechtbuch aus dem

Jahre 1459. Edited

by Gustav Hergsell (Prague: Selbstverlag, 1889). A splendid example of

such manual is Das Solothurner Fechtbuch (1423). Edited by Charles

Studer (Solothurn: Vogt-Schild AG).

Journal of Western Martial Art

About the author: , who currently resides in Hungary, is a historian of the Middle

Ages, with special reference to social and economic issues and military

history, enthusiast and practicioner of medieval martial arts. He is currently

working on a Ph.D. project concerning a functional analysis of sixteenth

century comments to the teachings of Johannes Liechtenauer.

numbered every odd one in the upper right corner, starting from page 4

which is given No. 1. Page 1 contains a date 1549, a name of one of the

manual's owners,[1]Vonn

Baumans, and the word Fechtbuch, while pages 2 and 3 are blank.

This manual seems to consist of two different Fechtbücher (for the

sake of convenience called further A and B), which were put together and

later given a common pagination.[2]

Part A (No. 1 recto-No. 75 recto, and No. 108 verso; thus consisting of

151 pages) is probably from the second half of the fifteenth century, on

account of both the representations of arms and armour on No. 1 verso (full

plate armours and armets) and No. 2 recto, andthe

details of costumes on No. 108 verso.[3]

On the other hand, part B (No. 76 recto-No. 108 recto; 66 pages) is probably

of much earlier origin, which, on account of the details of armour (bascinets

without visors or bascinets with early types of visors; mail hauberks;

garments worn on the cuirasses) can be dated to late fourteenth-early fifteenth

century.[4]

numbered every odd one in the upper right corner, starting from page 4

which is given No. 1. Page 1 contains a date 1549, a name of one of the

manual's owners,[1]Vonn

Baumans, and the word Fechtbuch, while pages 2 and 3 are blank.

This manual seems to consist of two different Fechtbücher (for the

sake of convenience called further A and B), which were put together and

later given a common pagination.[2]

Part A (No. 1 recto-No. 75 recto, and No. 108 verso; thus consisting of

151 pages) is probably from the second half of the fifteenth century, on

account of both the representations of arms and armour on No. 1 verso (full

plate armours and armets) and No. 2 recto, andthe

details of costumes on No. 108 verso.[3]

On the other hand, part B (No. 76 recto-No. 108 recto; 66 pages) is probably

of much earlier origin, which, on account of the details of armour (bascinets

without visors or bascinets with early types of visors; mail hauberks;

garments worn on the cuirasses) can be dated to late fourteenth-early fifteenth

century.[4]