"How's your elephant?"

An Asian style Martial Artist looks at the WMAW

Journal of Western Martial Art

by Deborah Klens-Bigman, Ph.D.

Rapiers, daggers, broadswords, knights in shining suits of armor - stuff

of childhood fantasies. As a kid, I would have killed (or at least fought

a duel) for a chance to attend the Association for Historical Fencing's

Third Annual Western Martial Arts Workshop, held October 12, 13 and 14,

2001, at Riverside Church, in New York City.

Rapiers, daggers, broadswords, knights in shining suits of armor - stuff

of childhood fantasies. As a kid, I would have killed (or at least fought

a duel) for a chance to attend the Association for Historical Fencing's

Third Annual Western Martial Arts Workshop, held October 12, 13 and 14,

2001, at Riverside Church, in New York City.

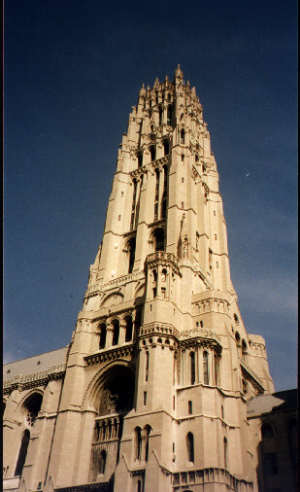

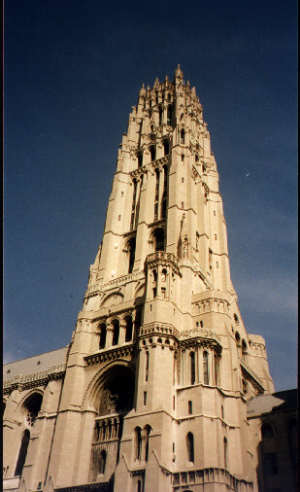

The location was particularly apt. Riverside Church, located

just north of the Columbia University campus on the City's West Side, is

wonderful Gothic-style structure, with plenty of medieval nooks and crannies.

As AHF president Ramon Martinez and organizer Fawzi al Nawal pointed out

in their opening remarks, a spiritual setting was very appropriate for

what the weekend held in store: an exploration of European martial history,

practice and culture steeped in a spiritual tradition that our modern secular

lifestyle has all but forgotten.

The weekend consisted of presentations and workshops given

in the Assembly Hall ($100 in advance, $125 at the door) and master classes

(additional $50 each, or $120 for three), given on the 9th and 10th floors

of the Tower. These were wonderful rooms with mullion windows overlooking

the City and New Jersey across the Hudson.

As an EJMAS reporter, I was given a press pass to wander

any classes and workshops I could get to, with the proviso that I not actively

participate without paying the requisite fees. The latter proved difficult

as I found myself sitting at the periphery of classes, practically twitching

to get involved. Though I hung up my fencing foil 14 years ago, there was

enough that was familiar in the historical styles to make me miss the camaraderie

and fun that Western martial arts study can be.

There were more classes and workshops offered than one

person could possibly attend, starting bright and early Friday morning

and going until late at night for the three days, with Sunday morning off.

Instead of spending a short time at each class, I opted to observe full

classes and workshops. This plan necessarily limited my experience. The

classes I observed were mostly for bladed weapons, but stickfighting and

wrestling were also included in the schedule. If the activities I attended

were representative, the WMAW offered a tantalizing array of martial arts

through almost 1000 years of European history. (The full array of offerings

are available at AHF's website - www.ahfi.org

- as are teacher biographies).

Unfortunately, due to recent events in NYC and subsequent

chaos in air travel, some events had to be canceled or rearranged at the

last minute. The number of participants was also lower than the previous

year, at 60 paying participants, with 20 teachers and assistants. (Toronto

last year had a total of 130 people including spectators and teachers.)

It is to the credit of the AHF that they decided to go ahead with this

year's event in spite of the difficulties.

After a protracted registration time to allow for the horrendous

traffic that has become NYC's lot of late, the first session began only

slightly behind schedule. "The Foundations of Swordsmanship," organized

by the International Masters at Arms Federation, explored the basics that

apply across systems of Western martial arts, from broadsword to rapier

and small sword; which is to say from approximately the 13th to early 20th

centuries. Maestro Ramon Martinez and other teachers took turns presenting

elements to be found in common. Several things stood out. First was the

teachers' broad sense of understanding across genres. For example, David

Cvet, known for his interest in 14th century weapon styles, easily cross-referenced

his material to the use of later weapons, such as rapiers. The second point

was how many of the principles and concepts being explained were similar

to what one encounters in Asian martial arts. M. Martinez emphasized the

idea of movement from what he referred to as "the base." He was actually

referring to what a Japanese-style practitioner would refer to as koshi

- the use of the hip/lower back/abdomen that is one of the essential principles

of practice. The body moves, from the "base," with the weapon, and the

weapon moves in advance of the body.

This session set the tone of the weekend. As David Cvet

pointed out, "Bodies are bodies," and they all move in certain ways; but

interpretation of those movements can range widely. What is especially

interesting is that when it comes to wielding weapons, things are not so

different after all between East and West.

Next, Jessica Rechtschaffer gave a very informative presentation,

"Choosing Quality Armor for Western Martial Arts."

Among many other things she spoke about the importance

of historical research on the part of the client before ordering a piece

from an armorer (i.e.; don't expect her to know the period or style needed),

and the importance of safety in looking for quality construction (and paying

for it). I had a brief opportunity to speak with her afterwards. Jessica

lives in the Bronx, and trained in medieval history. Though she doesn't

make a full-time living as an armorer, her passion for the craft is obvious

and her workmanship is excellent.I had an opportunity to try on a gauntlet

- it was perfect.

By this time, the participants had broken out into several

master class sessions, but I stayed on for David Cvet's "Armoured Combat."

It was a pretty easy decision, as the eager anticipation on the faces of

the participants, armed with "wasters" (wooden long swords) suggested this

session would be fun.

And it was, though, for whatever reason, the session evolved

into a sort of barely-controlled chaos, in which participants not only

did the techniques demonstrated by Cvet and his students, they spontaneously

worked variations on them as well, all amid a certain amount of good-humored

discussion. Cvet pointed out that in unarmored versus armored combat, "armored"

doesn't just mean the techniques are different, the rules are different

as well. Unarmored combatants strike at each other from a distance, whereas

armor makes weapons less effective. Ultimately, you must close with your

opponent and throw him down in order to defeat him. As a result, weapons

for armored combat are heavier and blunter. Though a two-handed long sword

may in some ways remind one of a Japanese katana, the method for use is

totally different.

In the late afternoon, I went to Bob Charron's "Recurring

Concepts and Techniques in Fiore Dei Liberi's Flos Duellatorum." Fiore

Dei Liberi was a fencing master to the Italian court of Niccolo D'Este,

the Marquis of Ferrara.

By all accounts, Fiore was very good at his craft; so good

in fact he was challenged on at least five occasions by other masters,

and he beat every one of them. Sometime around 1400, his students persuaded

him to write a treatise explaining his system of combat. The result is

the Fiore di Battaglia (or, in Latin, the Flos Duellatorum).

Many scholars who write about Asian martial arts consider

the elements that define a martial art system. One characteristic is that

it must be a coherent set of techniques that can be taught and passed on

beyond the lifetime of the teacher.

The Flos Duellatorum organizes a system around

a set of postures and movements that work for empty hand, dagger, broadsword

and other weapons. Once the student has mastered the empty hand techniques,

she can make the transition to weapons with relatively little adjustment,

provided she remembers and applies the techniques and postures already

learned.

Charron also took time to explain some of the conceptual

background to Fiore's system. As was common in that time period, Fiore

equated parts of the body with accepted characteristics of certain animals,

illustrated in his manuscript. A lynx, holding a caliper, sits above the

head of a 15th century man. Charron explained that in medieval culture,

people believed the lynx had the power to read a person's thoughts; hence

the lynx above the head suggests the power of perception.

The elephant, located at the feet, implied

stability and surefootedness. (Throughout the class, Charron would exhort

the students to look after their posture and footwork by shouting "How's

your elephant?") The tiger, located at the right, stood for speed, but

also for ferocity. He was therefore balanced on the left with the lion,

for bravery and justice.

Over and over again, Charron returned to the basic postures

and applications as he went from empty hand to daggers to broadsword during

the session. Charron is working on a definitive translation and commentary

of the Flos Duellatorum, which will hopefully be published next year.

By this time on the first day (7:00 p.m.), I returned home,

but presentations continued with lectures by Maestro Jeannette Acosta-Martinez,

Maestro Ramon Martinez and a scheduled master class. Friday's activities

were expected to wind up by 10:00 p.m.

Saturday morning, I made my way to the brilliantly sunlit

10th floor Tower room for Maestro Ramon Martinez's "La Verdadera Destreza:

the Art, Science and Philosophy of Spanish Swordsmanship." This was a 17th-18th

century rapier class, and it had a distinctly different style and tone

from the previous sessions. This was partly due to the nature of the rapier,

as it was historically practiced by a certain genteel social class. There

is a greater distance between opponents, and, while people frequently died

by dueling, rules of "first blood" could be invoked to preserve honor,

but avoid serious injury.

The other reason for the change was the Maestro

himself - very distinguished with graying hair and beard, and movements

as lithe as a cat's (or a lynx's). Maestro Martinez is extremely well-versed

in the history, philosophy and tactics of Spanish rapier. He was also able

to dispel some myths I held from watching too many movies. For example,

the "circle of combat" seen in the recent film Zorro was rarely if ever

used for training; but the concept of the circle, in which combatants faced

each other at an optimal distance, was extremely important. As M. Martinez

put it: "The circle is in your head." Attacks with a Spanish rapier always

begin from off the opponent's center line, though at all times the weapon

must be kept in line with the target. While this contradicts sport fencing

rules, it makes perfect sense from a combat perspective. I left this session

realizing that film depictions of Western rapier fighting are just as inaccurate

as the more obviously-silly Asian stage combat interpretations.

After lunch, it was back to the Assembly Hall for Ian Johnson's

demonstration of his reconstruction of poleax techniques from the Jue de

la Hache. A poleax is just what it sounds like: an ax on a pole about five

feet long overall, but with a hook or spike opposite the ax-blade side

that could be used, literally, for "hooking" your opponent or his weapon.

Aside from the hook, applications for the poleax somewhat resembled those

for Japanese naginata, in that you could fight your opponent at some distance

or "choke up" on the pole for closer-in fighting. You could also reverse

the weapon and use the butt-end for striking. On the other hand, poleax

technique for opponents in armor followed David Cvet's "rules": close-in

grappling, and with the winner determined by takedown.

Following guys in armor swinging at each other with poleaxes,

I rushed to catch the rest of Maestro Jeannette Acosta-Martinez's "From

Liancour to Angelo, the School of the French Small Sword." As a former

foil fencer, I had a particular interest in seeing this class. Also, M.

Acosta-Martinez was the only woman conducting a master class at this Western

Martial Arts Workshop.

If one took only a casual glance, the postures and movements

looked a great deal like foil fencing. Actually, the French Small Sword

is a heavier weapon, often equipped with what sport fencers call a "figure

eight" guard. While some of the postures looked similar (the unarmed hand

is held above the shoulder, as in foil), the techniques are both more subtle

and more comprehensive. M. Ramon Martinez, who was assisting at this session,

pointed out that, contrary to what I had always been led to believe, French

Small Sword was a tradition that actually had not entirely disappeared

by the 20th century.

There were still a handful of European masters

keeping the tradition alive from whom he, and subsequently, M. Acosta-Martinez,

were able to learn.

M. Acosta-Martinez was a very knowledgeable, but gentle

teacher. Students, in pairs, were given techniques to practice while she

and M. Martinez walked around the room making corrections. One participant

kept assuming an Italian rapier-style stance, wherein the unarmed hand

is held above and in front of the chest, while everyone else was endeavoring

to do the correct posture. No one suggested he change it, however.

Stephen Hand's session, "Saviolo System of Rapier and Dagger,"

immediately followed, so I had a chance to see and compare the previous

session to Italian rapier. Hand, from Australia, has spent a great deal

of time studying Saviolo's philosophy and technique. He started the session

with the solo rapier. The unarmed hand is held near the face, high and

in front of the chest, so one could grasp the opponent's hand or weapon

if the opportunity arose. In the course of the session, however, Hand pointed

out that he believed Saviolo's reason for positioning the unarmed hand

where it was, was simply to make the transition to using a dagger with

a rapier easier, which he considered a superior technique. The class consisted

of attacks, counters and disarms, with some grappling.

Participants in the rapier and small sword sessions mostly

wore gloves and white fencing jackets, though occasionally someone would

wear a period-style padded jacket (Hand wore a 17th century-style, heavy

leather vest). Everyone used fencing masks in these sessions. This would

make it difficult for beginners to take part; in fact everyone in the rapier

and small sword sessions seemed to have at least some previous experience

in either period or sport fencing.

After a very short break (owing to the number of sessions,

there was no real dinner break), I returned to the Assembly Hall for the

Armoured Tournament. Unfortunately, there were only three participants

this year (last year's tournament in Toronto had many, many more). Rather

than a full-fledged tourney, the participants opted for a demonstration-style

format.

Bouts in a medieval tournament were of two types: "for

pleasure," in which participants would fight to a certain number of landed

blows with various rules applying, or as a "grudge match" in which the

winner would be determined by takedown, with fewer niceties. The three

participants variously matched up, with most bouts being "for pleasure."Combat

in armor is LOUD. The sound of steel weapons clashing on steel breastplates

was awesome.

I can only imagine the volume level that a

full battle (or multiple, simultaneous tournament bouts) might make. There

was one bout as a grudge match, to show us what one looked like, and the

biggest guy did not win. Like a sumo match, besting your opponent may rely

on strategy and leverage rather than size and strength. There was no "winner"

per se, but the judges awarded a dagger as a trophy to the participant

who, in their opinion, showed the most spirit in the various encounters.

Sunday got off to a slower start. Long-running church activities

in the morning delayed the Workshop by at least an hour, and there were

some schedule changes as well. I was happy not to have missed Craig Johnson's

presentation on "Choosing and Purchasing a Quality Weapon: Criteria to

Look For." Not only did he discuss his methods for making "working reproduction"

weapons, he was able to give advice to collectors on how to spot fakes

when looking to buy an authentic period weapon. For example, distal tapers

are authentic, but they are hard to produce, so many fakers use a simpler

method to produce a taper closer to the end of the blade. A real sword

will not be entirely straight, owing to period tempering methods. Therefore,

if the blade is perfectly straight, it is probably recent.

Next, Christoph Amberger gave a presentation on German

Schlager technique. Schlager evolved from traditional dueling methods that

could be seen late into the 19th century. Practitioners wear a heavily

padded sleeve on their weapon hand, and fight close-in. Real, as opposed

to practice, bouts still consider the face a prime target (using eye, nose

and sometimes jaw protection). Duellists fence for first blood. Being cut

during a bout is not considered an embarrassment, but one can lose a bout

on "moral grounds" for backing away from an opponent.

There was a short break before the Rapier and Small Sword

Tournament. M. Ramon Martinez directed, and there were four judges. The

bouts were circular, and not linear like sport fencing. Masks were in use,

and bouts were for three points. A thrust to the chest or face was worth

three points (considered killing or disabling blows), with one point given

for other targets. There were so many rules of combat, it took M. Martinez

almost 10 minutes to read them all.

The rules stressed courtesy and fair play between opponents,

courtesy to judges and the director, and finally, courtesy from the audience

as well. Needless to say, instead of the raucous cheering that accompanied

Saturday night's Armoured Tournament, we applauded politely at the end

of each bout. Bouts were conducted in almost total silence except for the

click of various weapons. Unlike the Armoured Tournament, there was an

actual winner, determined by direct elimination.

There were more events to follow, but it being Sunday night,

and Monday a working day, I took my leave of the Third Annual Western Martial

Arts Workshop. I can truthfully say a good time was had by all. Though

I am not quite ready to give up my katana for a broadsword, I learned a

lot about my own martial heritage, which is surviving better than I ever

would have thought.

Journal of Western Martial Art

I would like to thank Kim Taylor and David M. Cvet for arranging

my attendance the event; and Fawzi al Nawal and Maestro Ramon Martinez,

for answering questions and extending me the courtesy of attending any

classes I chose.I hope next year's event, to be held in Chicago, will be

even bigger and better. For more information on the Association for Historical

Fencing, go to www.ahfi.org.

Copyright © 2001 Deborah Klens-Bigman, Ph.D.

Rapiers, daggers, broadswords, knights in shining suits of armor - stuff

of childhood fantasies. As a kid, I would have killed (or at least fought

a duel) for a chance to attend the Association for Historical Fencing's

Third Annual Western Martial Arts Workshop, held October 12, 13 and 14,

2001, at Riverside Church, in New York City.

Rapiers, daggers, broadswords, knights in shining suits of armor - stuff

of childhood fantasies. As a kid, I would have killed (or at least fought

a duel) for a chance to attend the Association for Historical Fencing's

Third Annual Western Martial Arts Workshop, held October 12, 13 and 14,

2001, at Riverside Church, in New York City.