Mar

itself, as well as a troop of burgesses from Aberdeen who justifiably feared

that the Gaelic clansmen would sack the city even though they did not dispute

Donald's claim to the earldom.

Mar

itself, as well as a troop of burgesses from Aberdeen who justifiably feared

that the Gaelic clansmen would sack the city even though they did not dispute

Donald's claim to the earldom.Journal of Western Martial Art

January 2000

Neil H. T. Melville

On the 24th of July 1411 Donald, Lord of the Isles, at the

head of a Highland army numbering, so it was said, 10,000 men, arrived

at the village of Harlaw near inverurie, less than 20 miles from Aberdeen.

Donald claimed the Earldom of Ross by right of his wife and was determined

to assert his title by force of arms against the counterclaim of the regent,

the Duke of Albany, on behalf of his son, John, Earl of Buchan. At the

head of the largest army to come out of the West Highlands, Donald had

already taken Dingwall and Inverness, where he gathered more men from the

northern clans, defeated opposition from Clan Mackay and harried the lands

of Alexander Stewart, Earl of Mar, his cousin. In the south Albany had

been slow to meet the challenge, but Mar had raised an army of knights

and spearmen from the neighbouring districts of Angus, Buchan and  Mar

itself, as well as a troop of burgesses from Aberdeen who justifiably feared

that the Gaelic clansmen would sack the city even though they did not dispute

Donald's claim to the earldom.

Mar

itself, as well as a troop of burgesses from Aberdeen who justifiably feared

that the Gaelic clansmen would sack the city even though they did not dispute

Donald's claim to the earldom.

Accounts of the battle in later chronicles vary considerably - each

side apparently won a famous victory! The Highlanders probably carried

shields, broadswords, axes, bows and knives, while their chieftains wore

the tall bascinets and quilted aketons represented on so many of the West

Highland tombstones. They were drawn up in the traditional crescent shape

with a centre, two wings and a reserve. Mar's force was much smaller, about

2,000 men, but many of them were mounted, wore mixed plate and mail armour

and carried lances, battleaxes and swords. It was deployed in one main

body with two smaller wings. The two armies fought fiercely but indecisively

all afternoon and evening in a battle so bloody  that

the field has since been called Red Harlaw. A thousand or so of the Islesmen

were killed and almost as many of the Lowlanders before night brought a

halt to the slaughter: "a cruel and bloody day wherein fell so many eminent

and noble personages as scarce ever perished in one battle against a foreign

enemy for many years before". Mar himself escaped to Aberdeen but many

of the most distinquished knights of this army remained dead on the field.

The bards of Clan Donald claimed a heroic victory, as did Abbot Bower,

in his contemporary chronicle, for Mar; but Donald withdrew to the Isles

and the earldom of Ross went to Albany's son, the Earl of Buchan.

that

the field has since been called Red Harlaw. A thousand or so of the Islesmen

were killed and almost as many of the Lowlanders before night brought a

halt to the slaughter: "a cruel and bloody day wherein fell so many eminent

and noble personages as scarce ever perished in one battle against a foreign

enemy for many years before". Mar himself escaped to Aberdeen but many

of the most distinquished knights of this army remained dead on the field.

The bards of Clan Donald claimed a heroic victory, as did Abbot Bower,

in his contemporary chronicle, for Mar; but Donald withdrew to the Isles

and the earldom of Ross went to Albany's son, the Earl of Buchan.

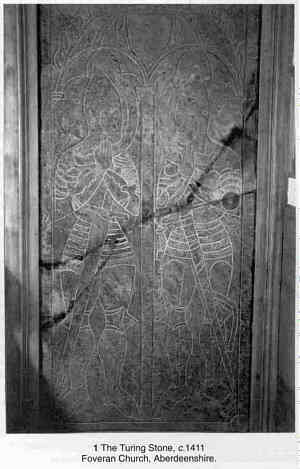

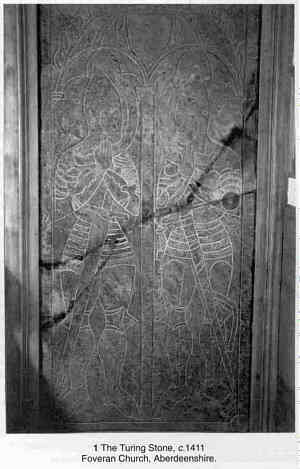

One of the knights who were killed in the battle of Harlaw was, almost certainly, Gilbert of Grenlau (Greenlaw). His uncle, the bishop of Aberdeen, also named Gilbert de Greenlaw, was present the following Christmas at celebrations held by the Earl of Mar at Kildrummy Castle. The younger Greenlaw would have been one of the Buchan gentry who lost their lives in the battle together with the provost and great part of the burgesses of Aberdeen. Many families lost not only their head but every adult male. Greenlaw is buried at Kinkell church, just the other side of Inverurie, and his tombstone, depicting the knight in his full harness of plate and mail and wearing a sword typical of the type associated with the Highlands (angled quillons with spoon-shaped terminals, prominent langet) is justly well known and widely published. Far less well-known, in fact not published at all, to my knowledge, in Arms and Armour literature, is a tombstone in the church at Foveran, about 13 miles due east of Harlaw (Fig. 1).

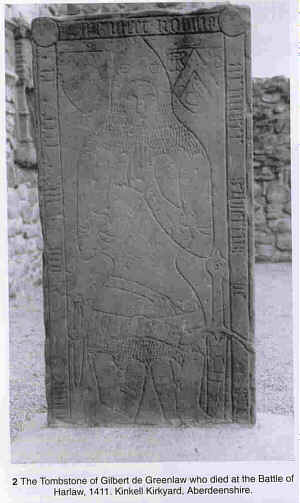

This

stone is of grey sandstone, approximately 222cm x 103cm x 14cm and cracked

across the middle. It bears an incised representation of two armoured figures

in an elaborate architectural framework which includes a heraldic shield

but mysteriously no names or date - no inscription at all in fact except

for an initial "Hic Iace[t/nt]". It appears that the slab has been recut

at some time, which weakens any attempt to identify and date the figures,

and some of the carving is crude. Nevertheless I shall endeavour to suggest

that the slab commemorates two members of the Turing family of Foveran

who were in all likelihood killed at Harlaw wielding their two-handed swords,

of which this slab offers the earliest representation in Scotland, or even

Britain. The rest of the grave inscription, the charges on the shield and

any inscription on the scrolls, which hang delicately in front of the faces

of each figure, were doubtless originally painted on.

This

stone is of grey sandstone, approximately 222cm x 103cm x 14cm and cracked

across the middle. It bears an incised representation of two armoured figures

in an elaborate architectural framework which includes a heraldic shield

but mysteriously no names or date - no inscription at all in fact except

for an initial "Hic Iace[t/nt]". It appears that the slab has been recut

at some time, which weakens any attempt to identify and date the figures,

and some of the carving is crude. Nevertheless I shall endeavour to suggest

that the slab commemorates two members of the Turing family of Foveran

who were in all likelihood killed at Harlaw wielding their two-handed swords,

of which this slab offers the earliest representation in Scotland, or even

Britain. The rest of the grave inscription, the charges on the shield and

any inscription on the scrolls, which hang delicately in front of the faces

of each figure, were doubtless originally painted on.

First the family: a William de Turin was granted the charter of Foveran by David II (1329-71); he was succeeded by his son, Andrew Turin (1388-1424), and by successive Turins of Foveran (becoming Turing by 1613). The only other notable family in Foveran was that of Forbes, who intermarried with the Turings. The arms of Turing were a bend sinister carrying three boars' heads; those of Forbes were three bears' heads in an inverted V pattern. Luckily the shield on the slab bears an incised bend sinister, which clearly suggests that Turings rather than the Forbes, with the boars' heads presumably painted. If the two figures were killed at Harlaw then they would be brothers/sons of Andrew Turin. The fact that the slab commemorates two adult male members of the same family certainly suggests death in battle, and Harlaw was the only likely occasion in the first quarter of the 15th century - which brings us to the date of the slab.

The figures are represented within an architectural frame, as was common in the late 14th and the 15th centuries. If we follow the conventional style of contemporary brasses in England, then the figures are recombent; but there are no small animals to support their feet and no helmet or cushion to support their heads, and since they are turned slightly, looking towards each other, they could just as easily be imagined as standing under their canopy. The frame consists of a major arch containing two bays each covered by a cusped trefoil arch and separated by a pillar with a round cushion capital and a stepped base. The space between the subsidiary arches and the top of the main arch is occupied by an armorial shield and decorative tri-petals.

This fairly simple gothic canopy can be paralleled in window tracery at Melrose Abbey dating to the rebuilding of c.1400-20. Similar canopies with cusped arches, though admittedly with more elaborate pinnacles and other details, are shown on many English brasses of the period, e.g. the Swynborne father and son, 1412, at Little Horkesley, Essex (the figures separated by a pillar, as at Foveran), or Sir W. Fienlez, 1402, at Hurstmonceaux, Sussex. A very close parallel for the scrolls or labels floating by the faces of the figures, again on a double stone, is the incised slab of John de Galychtly and wife, c.1420, at Longforgan, Perthshire, (Fig. 3) The small roundels at each corner of the outer frame are matched exactly by those on the Greenlaw slab at Kinkell (Fig.2). Architecturally speaking, then, the Foveran slab can comfortably be placed in the period 1350-1450.

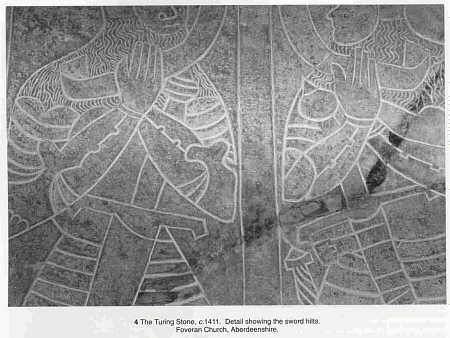

Despite some crudeness in the cutting, the armour worn by the two figures

is recognisably straightforward. Each wears a very tall, pointed, bascinet

sloping backwards to the peak, one of which is shown with a circle at the

side of the brow which is probably intended to represent the pivoted hinge

plate for a detachable visor (more appropriately positioned than those

on the Greenlaw effigy). Attached to each bascinet is a large aventail

with scalloped edge, covering the shoulders, identical to Greenlaw's. A

globular breastplate, without jupon, is accompanied by a fauld of five

and seven lames respectively, below which projects the edge of a mail shirt,

again like Greenlaw, though he is wearing a jupon. The arm-defences of

both figures are very similar, consisting of laminated spaulders attached

to the articulating lames of the couters which in turn  articulate with the tubular, hinged lower cannons. The only difference

between the two is that the couters of the dexter figure have a heart-shaped

besagew attached to the side, a feature which is very old-fashioned even

after 1350 let alone after 1400. Greenlaw has couters with heart-shaped

wings articulating with tubular, hinged, lower cannons (as at Foveran)

but with a single, gutter-shaped, upper-arm defence. The carving of the

leg-defences of the dexter Foveran figure is incomplete, apart from the

sharply projecting poleyns, but the sinister shows plate cuisses over mail

chausses, poleyns with sharply pointed concical caps, greaves of two plates,

shaped to the leg, hinged on the inside and terminating at the ankle, and

sabatons of contemporary shoe shape with two horizontal lames across the

middle of the foot and a pointed toe piece. One of the four ankles is shown

with a prick spur.

articulate with the tubular, hinged lower cannons. The only difference

between the two is that the couters of the dexter figure have a heart-shaped

besagew attached to the side, a feature which is very old-fashioned even

after 1350 let alone after 1400. Greenlaw has couters with heart-shaped

wings articulating with tubular, hinged, lower cannons (as at Foveran)

but with a single, gutter-shaped, upper-arm defence. The carving of the

leg-defences of the dexter Foveran figure is incomplete, apart from the

sharply projecting poleyns, but the sinister shows plate cuisses over mail

chausses, poleyns with sharply pointed concical caps, greaves of two plates,

shaped to the leg, hinged on the inside and terminating at the ankle, and

sabatons of contemporary shoe shape with two horizontal lames across the

middle of the foot and a pointed toe piece. One of the four ankles is shown

with a prick spur.

In dating this armour it has to be borne in mind that Scotland was on the fringe of Europe and that the latest fashions in armour from Germany or Italy or even England took a while to arrive, were expensive and not necessarily suited to local conditions. A natural conservatism and reluctance to abandon equipment which was still perfectly serviceable meant that styles which had gone out of fashion in the rest of Europe could still be in use in Scotland years later.

There is no problem with the tall bascinet, drawn up to a point rear

of centre and fitted with a detacheable snouted visor, which was an international

type and very common from c.1370 to c.1420, though its accompanying aventail

began to be replaced by a plate bevor c.1400-10. The Foveran bascinets

may seem to be exceptionally tall but the effigy of Sir John Drummond,

c.1360-70, at Inchmahome Priory in Perthshire, shows one of similar size.

The globular breast-plate accompanied by a fauld of several lames or hoops

seems to have become popular by 1380 and can be seen on a good number of

English effigies until the middle of the 15th century. It is

not surprising that the Foveran figures are shown without jupons, even

though Greenlaw is wearing one; the years around 1410 are just when the

jupon was beginning to be discarded. It is worn on English brasses of 1400,

1402, 1405, 1408, 1412, and is absent on ones of 1400, 1408, 1410, 1412,

etc; the 1412 brass, mentioned in both lists above, commemorates a father

and son (Swynborne, of Essex), and depicts the father, presumably, wearing

not only an old-fashioned jupon but also a mail aventail, in contrast to

his son's uncovered breastplate and plate bevor. Interestingly the magnificent

silver altarpiece in Pistoia cathedral, created in 1367-71, shows several

soldiers, who are attending the execution of St. James, in "white" armour

- bascinet and aventail, rounded breastplate with a medial ridge and a

multi-hooped fauld over a mail haubergeon. The figure of St. George (1372)

on the façade of

Basle cathedral is armoured in very similar fashion to the Pistoia

soldiers.

The vambrace with laminated spaulder was in general use during the second half of the 14th century and the early 15th, though here the lames of the spaulder appear to meet the articulating lames of the couter without any intervening upper cannon. Cuisses consisting of a single large plate fastened round the thigh with straps, which is what seems to be shown here allowing for the crude uncertaincy of the carving, had been developed by the last quarter of the 14th century, although the mail chausses worn by both the sinister Foveran figure and by Greenlaw were much less common by 1400 - enclosing cuisses of plate buckled together are depicted on most English brasses after c.1380 (surviving harnesses of the period show that the inner back of the thigh was left unprotected as being least vulnerable on horseback and affording more sensitive control of the horse).

Before looking at the swords, which, because of their great size, are of considerable interest, I would like to introduce in comparison four dated effigial slabs. In the parish church of Creich in Fife, on the south bank of the Firth of Tay, is an incised tomb slab commemorating David de Barclay and his wife, Helena de Douglas. David's date of death was left blank (MCCCC..) and never completed; the stone, however, was clearly carved, for both of them, on the occasion of the wife's death, in 1421 (29 Jan). While the effigy is not particularly clear, due to weather damage, it can be made out that Barclay is shown bare-headed, wearing (probably) a mail collar, laminated spaulders with hinged upper and lower cannons of the vambraces, winged couters, a globular breastplate with hooped fauld (no jupon) over a mail haubergeon, an elaborate sword belt with a sword of standard European form (with turned-down quillon tips), buckled cuisses and greaves, articulated poleyns and laminated sabatons. Other details, unfortunately, are unclear.

Opposite Creich, on the north bank of the Tay, near Dundee, in the village of Longforgan there was discovered in 1899 under the church floor a splended incised tomb slab commemorating John de Galychtly and his wife. This, too, was cut in advance; in fact before the death of either of them, since both dates have blanks left for the month and the exact year (MCCCC..). The carving and the lettering, however, together with the decorative canopy work and the style of incision are so similar to the Creich slab, only 5 miles away as the crow flies, that it is likely that both slabs were carved by the same mason at around the same time. Galychtly's effigy is in very much better condition, and the details of his armour are quite distinct. Unlike the Foveran figures he is not wearing a bascinet, nor, therefore, an aventail. Instead he has a mail collar and solid plate pauldrons with two articulated lames and a gutter-shaped upper arm defence. He has also abandoned chausses in favour of complete buckled cuisses, and the articulation of the poleyns with both cuisses and greaves is more elaborate. Very similar to Foveran are his globular breastplate and hooped fauld, his winged couters and tube-shaped lower cannons, his poleyns, pointed at top and bottom and projecting sharply at the centre, his hinged greaves, buckled on the inside, and his laminated sabatons. Unusually, buckled to the lowest lame of the fauld is a small, semi-ovoid, codpiece, composed of two apparently hinged lames. Overall his armour is similar to that of the Foveran figures while suggesting the developments which could be expected ten years later.

Surviving now only as a rubbing taken by Creeny in c.1890, a Belgian slab of 1413 in the church of Flemalle Grande, Liege, showed two brothers, both senior Hospitallers, side by side under separate canopies joined by a common pillar. Several aspects of the armour of Sir Jehan and Sir Arnout de Parfondrieu parallel those of the Foveran pair or John de Galychtly: They are shown as almost identical, each is bareheaded and wearing a mail collar, has small spaulders with an outer upper cannon strapped round a mail sleeve, articulated couters with heart-shaped wings and hinged tubular lower cannons. The body armour is concealed under a surcoat which just reveals plate cuisses articulating with simple bulbous poleyns and in turn with hinged and buckled greaves (oddly one knight has the hinges on the inside of the legs, the other has buckles on the inside). Each has laminated sabatons and rowel spurs, and is girt with a normal-size tapering-blade sword with straight quillons with tips angled towards the blade and a scent-stopper pommel.

Finally, another Hospitaller, Pierre de la Pymoraye, from Rennes in Brittany, who died in 1403 in Rhodes where a fine incised slab commemorates him. He, like the Foveran pair, wears a tall bascinet with full mail aventail and hinge pivots for a detached visor. His arm defences are indistinct but laminated spaudlers can be made out. He is wearing a jupon over a globular breastplate and plate cuisses over mail chausses. His bulbous poleyns, hinged greaves, laminated sabatons and rowel spurs are very similar to those of the Parfondrieu brothers, as are the quillons of his sword which are turned down at the tips. The pommel, can be dated to c.1404 by the coin of Guidantonio, Duke of Urbino, set into the pommel (Fig. 5).15 Similar crossguards, though with the tips slightly curled down rather than angled, can be seen on a large sword, formerly in Sir James Mann's collection, now on loan to the Royal Armouries, of c.140016 and on an English twohander of the mid-15th century in a private collection in Shropshire (Fig. 11).47 As early as 1180 a sword used by David to decaptitate Goliath on an illuminated page of the Winchester Bible18 shows both a ball pommel and straight quillons with angled tips.

In 1410 Maestro Fiore dei Liberi, at the court of Niccolo III d'Este,

Duke of Ferrara, wrote a fencing manual (Flos Duellatoryum or II Fior di

Battaglia) and illustrated it with numerous figures of well armed and armoured

combatants; several are shown wielding simple but unmistakable two-handed

swords (the grip is long enough to accomodate both hands separated by a

distinct space and the overall length of the sword approximates to chin

height) and wearing armour very similar to that on the Foveran stone (Fig.

12).19 In 1402, among his other legacies, including a silver-decorated

sword, Sir John Dependene of York bequeathed 'I thwahandswerd'.20

Two-handed swords were being made in Germany as early as the mid-14th century - several, both complete swords and blades only, are preserved in the Hofjagd - und Rustkammer, Vienna. Both English and Scottish examples survive from the second half of the 15th century, and the Scottish Lowland 'twahandswerd' shows a distinct relationship to these Foveran swords. The dexter sword, at least, I would suggest is a genuine twohander and dates from before 1411. It will be noticed that the sinister sword is not only slightly shorter but also has a slimmer blade and is wrapped round with a belt, which might suggest that it is intended to be girt round the waist. It could, however, represent an early example of the system of bearing the two-hander fastened by a belt over the shoulder. The usual objection to this theory, that it would be impossible to draw so large a sword from its scabbard, over the shoulder, may be answered by the existence of the scabbard of a two-handed sword with is fitted with a belt hook,21 suggesting that the sword and scabbard together were pulled out of the shoulder belt and only then was the sword withdrawn from its scabbard which was discarded to be retrieved later.

In conclusion, John Major, the Tudor historian, mentions that Donald, Lord of the Isles, en route to Harlaw in 1411 burnt the bridge at Inverness, and adds:

"John Cuming, a gentleman burgher, putting on his armour and head-piece, and two-handed sword, made such stout resistance at this nearest end of the bridge against the macDonalds that... if there were ten more like him in Inverness neither bridge nor burgh had been burnt."22

The author would like to thank for their help A.V.B.Norman, former Master of the Armouries, the Parish Ministers of Foveran, Creich and Longforgan, R.Woosnam-Savage, formerly of Glasgow Art Gallery and Museum; and David Oliver for his encouragement.

Journal of Western Martial Art