Purring

Journal of Manly Arts

August 2004

by Jason Couch

Original essay, 2004

McWilliams kicked Tavish five times in the twenty-third round; then the latter dropped like a log and refused to go on. His legs, from knee to ankle, were covered with cuts, and were raw as beefsteak.

Purring, or shin-kicking, was a popular English folk sport practiced from at least the 16th century and likely before. It existed both as a distinct contest of its own and as a facet of certain "loose hold" wrestling styles, such as Norfolk and Devonshire. By the mid-to-late 19th century, the sport was exported and practiced in America thanks to Cornish miners residing in Pennsylvania. By the end of that century the sport had all but disappeared, and now it exists only at fair exhibitions and in the mutated variants seen in children's games.

The Cotswold Olympicks

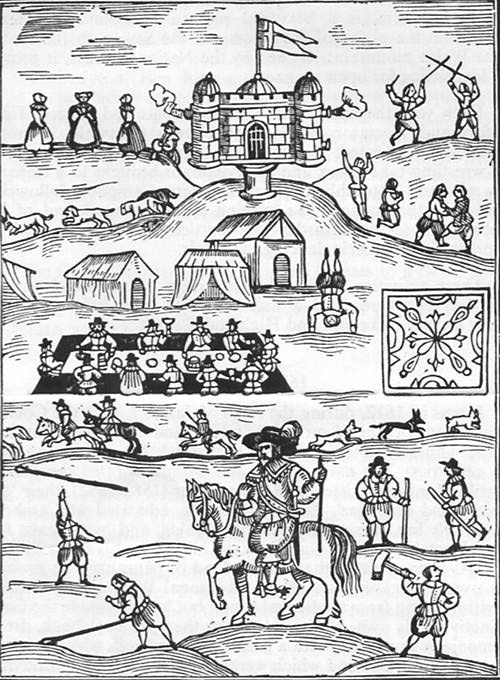

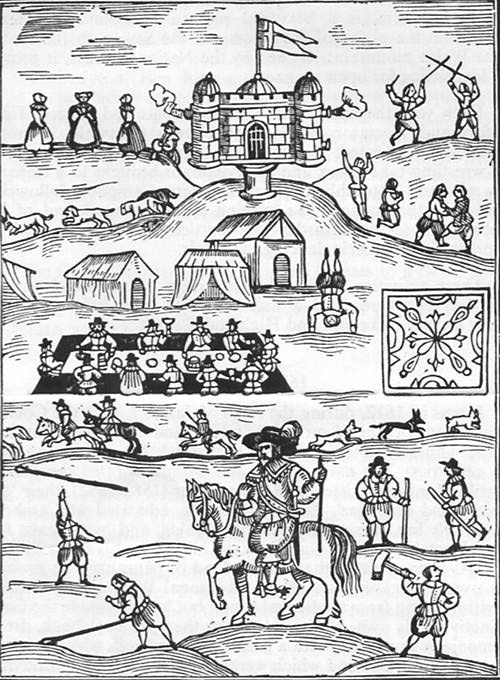

In 1612, attorney Robert Dover started the "Cotswold Olimpicks," an annual fair full of pageantry and spectacle. Medieval fairs were mainly about commerce: held seasonally or annually, merchants traveled to exchange wares while laborers attended to display themselves to prospective employers. Entertainment was subsidiary to the commercial purpose. Dover's Cotswold fair was just the opposite, primarily a celebration of sport and competition, with the headline events being contests such as singlestick, wrestling, jumping in sacks, dancing, and shin kicking. The link below shows a 1636 woodcut of the Cotswold Games. The Cotswold cut shows the emphasis upon sport and recreation, while surviving Thames Frost fair souvenir cuts from 1683 show the center thoroughfare given over to mercantile pursuits. The rider on the horse in the Cotswold cut is assumedly Robert Dover, who liked to appear on horseback wearing clothing formerly owned by James I, obtained for Dover by a servant to the king. http://www.stratford-upon-avon.co.uk/ccolymp.htm

In 1612, attorney Robert Dover started the "Cotswold Olimpicks," an annual fair full of pageantry and spectacle. Medieval fairs were mainly about commerce: held seasonally or annually, merchants traveled to exchange wares while laborers attended to display themselves to prospective employers. Entertainment was subsidiary to the commercial purpose. Dover's Cotswold fair was just the opposite, primarily a celebration of sport and competition, with the headline events being contests such as singlestick, wrestling, jumping in sacks, dancing, and shin kicking. The link below shows a 1636 woodcut of the Cotswold Games. The Cotswold cut shows the emphasis upon sport and recreation, while surviving Thames Frost fair souvenir cuts from 1683 show the center thoroughfare given over to mercantile pursuits. The rider on the horse in the Cotswold cut is assumedly Robert Dover, who liked to appear on horseback wearing clothing formerly owned by James I, obtained for Dover by a servant to the king. http://www.stratford-upon-avon.co.uk/ccolymp.htm

The pair shown in the top right quadrant immediately below the fencers are either wrestling or shin-kicking. Either way, elements of traditional shin-kicking are present: they are grappling above the waist, they are wearing shoes, and one man is kicking. It is unclear whether the kick is intended as a strike to injure the shin or intended as a sweep such as used in Cornish wrestling. Both the sweep and the direct kick were present in the different forms of loose hold wrestling of the day.

Kicking in Wrestling

Cornish wrestlers used the feet for sweeping rather than kicking, whereas kicking the shins during wrestling eventually became synonymous with Devonshire wrestling. However, when Richard Carew wrote his The Survey of Cornwall in 1602, he made no distinctions between the wrestling styles of Cornwall and Devon, implying that the styles of the two areas were synonymous. It appears that the Norfolk style's reputation for kicking preceded the Devonshire, which likely was identical to the Cornish at that time.

Thomas Parkyns, in his Progymnasmata: The Inn-Play, or Cornish Hugg-Wrestler (3rd ed.1727), labels the differences in styles the Inn-Play versus the Out-Play, whereas his contemporary, Zachary Wylde, calls it the Loose Holds versus the In Holds in his English Master of Defence (1711). Parkyns prefers the inside body-to-body throws of the Inn-Play, because the Out-Play, in his estimation, "depends much upon [the] plucking and tearing of clothes, wasting time to break his adversary's shins" and requires perhaps an "hour's fooling" around to finally get a lucky throw. Moreover, Parkyns "never could hear that the women approved of the Norfolk Out-Play, the rending and tearing of waistcoats, kicking and breaking of shins, and rendering them so tender, they could not endure to be rubbed." It is interesting that Parkyns mentions the Out-Play style as a Norfolk style, since it is eventually Devonshire that became so well known for its kicking. Even so, the Norfolk style was still known for its kicking well into the 19th century.

Charles Layton, the "Celebrated Game Chicken," described in his Whole Art of Norfolk Wrestling (undated) similar observations on the feelings of the fairer sex as Parkyns had described. Layton couldn't say that he had "ever heard of many women who approved of our Norfolk collar-hold play," and he believed "the rending and tearing of jackets for [the women] to mend" led many wrestlers to doctor their own shins since they couldn't count on assistance or even pity from the women stuck stitching up the clothing.

Layton describes tactical kicking in the various techniques he outlines, but it is in his poem that the real possibility of injury is shown. Layton describes the valor of two wrestlers willing to face the severely bruised shins that can result: "Another reply'd, why I know two/ Will stand the kicking till all is blue." Layton himself claimed his nickname because of his own pluck in the face of sore shins:

A wrestle took place scarce anywhere,

But what I went if poss'bly could,

And for the prize I firmly stood,

And as I so well did bear the kicking,

The nam'd and call'd me the game chicken

It wasn't just sore shins that could result, though, as Layton also mentions that "One man got kick'd so in four rounds, That in very few days died of his wounds." Even accounting for poetic license, those lines are reminders that a contest fought in shoes (with only stockings as shin protection) can do serious damage to the shins. Layton's version of good sportsmanship had the wrestlers retire to the public house after the bouts and dress each other's wounded legs.

By 1840, it was the Devonshire wrestlers that had taken over the reputation as shin kickers. That year Donald Walker, writing the first modern civilian self-defense manual in English, described the difference between the Cornish and Devonshire wrestlers in his Defensive Exercises:

The principal difference between these methods is that kicking the shins is a part of the Devonshire and not of the Cornish. The Devonshire men, therefore, wrestle with their shoes on, in order not to break their toes in kicking; and each takes advantage of this to bake the soles of his shoes, and thereby render his kicking as severe as possible. Thus, he who happens to have the hardest shoes has a decided advantage. Each has also the privilege of bandaging his legs, which is liable to a similar objection. It often happens, however, that after a severe match, the wrestlers leave the ring with the skin off their shins, almost from top to bottom.

Tom Conroy believes that the shoed and bloody shinned kicking of Devonshire wrestling flourished from around 1800 until the last third of that century before disappearing completely. (Conroy 1981). In 1855, it was still going strong when a visitor described a visit to Cornwall and observed two Devonshire men agree to wrestle, and "true to the old Devonshire practice," they kicked each other in the shins so vigorously that the blows could be heard above the noisy crowd watching. (White 1855). Later, once the Cornish matches started, shoes and stockings were stripped and the wrestling jackets were donned.

By the 1890s, the differences between the Devonshire and Cornish styles were still well remembered:

The Devonians had?a habit of wearing shoes; and?the shoes had been allowed to develop into a hideous weapon armed with a thick sharp edged sole. The Cornish men, who had never permitted such eccentricities, although they allowed the use of the foot in striking, stood out for a long time for exclusion of thick soles and the use of soft slippers. The Cornish and Devonshire wrestlers both freely used their legs in the attack. The Cornish man strikes with his heel or instep, using it somewhat as the French athletes in the savate, endeavouring to cut away the other man's legs from under him and thus render him an easier victim; the Devonian not only does this, but aims at the shinbones of the enemy, in the hope of inducing him through pain or faintness to yield the day.

(Pollock & Armstrong 1890). But it appears that Conroy was correct in that those differences had fallen by the wayside, as Muldoon wrote in 1891 that Devonshire kicking (including shoes with baked leather soles and a sheet iron insert) was a practice of "former times," and the only dissimilarity of his day was in the technical tastes of Cornish men for hugging and heaving (in-play), compared to the Devons tripping and jacket work (out-play). (Muldoon 1891). Likely the "civilizing process" and the loss of recreational time accompanying the Industrial Revolution hastened the downfall of the distinctive Devonshire style as well as the sport of purring. The longstanding preference of Cornish wrestlers to avoid kicking is particularly interesting, though, since the resurgence of purring in 19th century America is laid at their feet.

Purring in America

It is known that some Cornish men in the areas closest to Devon had favored the Devonshire kicking style over the tamer Cornish variant. During the 19th century, the main Cornish export was labor, with miners making up a large percentage of the males that left every year. Likely some of those miners practiced the Devonshire style. One area Cornish miners settled in America was the coal country of Northeastern Pennsylvania, where their expertise was put to good use in unearthing the prized anthracite discovered there. The coal in this area was not only abundant, but of such high quality that this area came to supply coal for 95% of the Western Hemisphere. Traditions carried over, and the same sporting men that wagered on boxing and wrestling laid bets on the occasional purring contest. During the 1870s and 1880s a handful of purring matches in this area were well publicized in the American press.

For instance, in 1879, a Cornish miner named David Davis boasted in a Shenandoah, Pennsylvania saloon that he could out "purr" any man in America. Davis had some reason to believe so, since he had won a previous match against noted purrer Tom Bosley around 1865, which was said to be the most recent match in the immediate area. New York's National Police Gazette captioned the contest as

A KICKING MATCH

Revolting Exhibition Among Pennsylvania Miners

of an Imported British Article of Brutal "Sport."

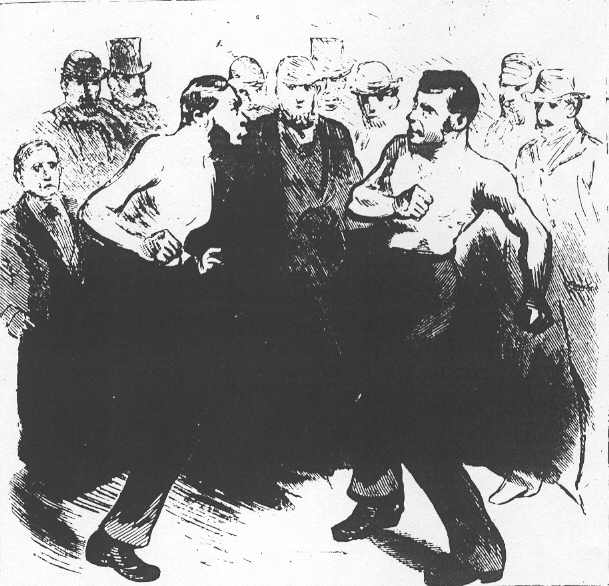

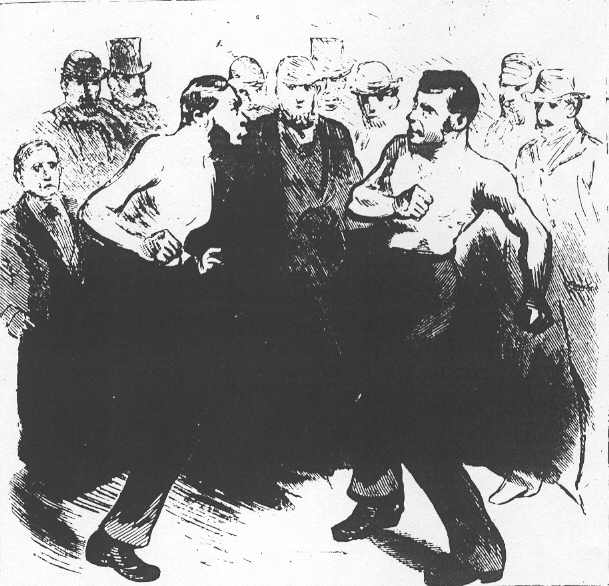

The use of the word "revolting" was ironic since the Police Gazette, then a newspaper recently taken over by Richard K. Fox, made a fortune by reporting on spectacle, sport, misfortune, and of course by displaying illustrations of hourglass-shaped entertainers. Later, when photography came into vogue around 1900, the public and the paper both suffered as the sympathetic illustrations of those shapely entertainers slowly became photographs revealing the harsh truth of their pear shaped forms. At any rate, the Police Gazette could not have been too morally outraged at the purring contest, since it saw fit to print a woodcut of their artist's conception of what the purring match would have looked like.

Obviously Davis's challenge was taken up or the contest would not have made the newspaper. Thomas Proudfit, another English miner, put up a $10 forfeit and each man eventually fought for $50 a side, a respectable enough sum for the day. The fancy rented out a bar-room where they wedged themselves into corners and on top of the bar so all could see. The two men stripped to their breeches, Proudfit slipping the new brogans over his woolen stockings, Davis the same over his cotton stockings. The men shook hands (an old Cornish wrestling tradition) and indicated they were ready to begin under the straightforward rules:

- nothing to cover the legs but breeches;

- no kicking a downed man;

- no kicks above the knee (an automatic forfeiture):

- no grappling; and

- the first to surrender loses.

Davis was the larger and more experienced of the two, but also less agile. Initially, the match was all feinting and dodging until the first kicks began to score in a furious flurry lasting about one minute. When time for the first round was called, both men had whiskey while their bruised and bleeding shins were examined by their seconds. As the fight wore on for eleven more rounds, the men limped on cut and bleeding legs trying to dodge the kicks, their corduroy breeches torn to ribbons below the knees. Finally, Davis refused to toe the mark for the thirteenth round. He was ready to give it up in the tenth, but the spectators jeered him and he kept on for the last two rounds, where Proudfit scored at will with Davis unable to return the favor.

After the match, Davis slumped in a chair while Proudfit danced a jig with a glass of water on his head, then both fighters had their shins attended. Their seconds first washed the fighters' legs, then applied poultices of rotten apples to reduce the inflammation and pain. Davis had to be carried home and Proudfit was said to be not much better off.

The Davis-Proudfit match is interesting on a number of levels. In some respects, the miners had taken a traditional English sport and adapted it to the current American boxing scene, as the same elements were present. The same spectators, the saloon location, the challenge, the forfeit money, the betting, rules including certain fouls, stripping to the waist, timed rounds, and the whiskey between the rounds are all elements adapted from the local boxing culture. The rules were not necessarily standardized, though, as other matches changed some rules, such as allowing grappling.

In 1883, a match occurred in Port Richmond, Pennsylvania, between a certain Grabby and a McTevish. This time they wore Lancashire shoes, toed with copper, and shoulder straps for their opponent to grasp. This fight was reported in a technical manner, with gory blow-by-blow accounts of the strikes given:

McTevish?made a straight toe kick for his opponent's right knee. Grabby deftly avoided the blow by spraddling his legs far apart and?brought his left foot around and caught McTevish on the outside of the right calf. The flesh was laid open to the bone, and the blood spurted out in streams?At the same instant?he gave Grabby what is known as the sole scrape. Beginning at the instep and ending just below the knee pan, Grabby's left shin was scraped almost clear of skin.

Grabby then lost hold of McTevish's shoulder strap and while looking up, received a double-footed kick for his inattention. He quickly returned with a kick on McTevish's knee, which caused him to drop, but he pulled Grabby with him to the ground. They were separated, and the round ended, being about sixteen minutes long.

Both men were a sad sight when they toed the mark for the second round, their legs had been bound in plaster, but blood still oozed out and the exposed spots looked like raw steak. Mercifully, Grabby immediately scored a straight kick to McTevish's injured knee that put him down and ended the fight for both men.

Some new elements were added in this fight. While there were rounds, they ended in the traditional bare-knuckle boxing manner, i.e., the round ended when one man fell to the ground. Without the added aspect of the grappling, such rounds could have lasted a long time before someone dropped of a kick. In fact, this match sounds somewhat similar to the classic Devonshire wrestling match, with their special kicking shoes and upright grappling.

Probably the best reported purring match ever held took place that same year and was picked up by newspapers across the nation. The contestants were again two Pennsylvanians: David McWilliams (142 lbs.), a Luzerne County miner who had kicked his way to victory in eleven previous matches, and Robert Tavish (130 lbs.), an ex-miner who ran a saloon in Manayunk, but was known as a boxer and wrestler. His main claim to fame was his offer the previous fall to wrestle the Englishman, Sam Acton, for $1000 a side.

They searched for a sporting house in Philadelphia to host the event, but due to prospective police interference, they ended up crossing the Delaware River and holding it in a rented room in Camden, NJ. The stakes were for $250 a side, which shows that there must have been considerable interest in the match. The rules used were similar to the Davis-Proudfit match four years earlier.

First, the men stripped to their knee breeches, which left their legs bare from the knee down. Then they donned new pairs of heavy brogans: McWilliams wanted the regulation horn-tipped shoes, but Tavish objected on the (sensible) grounds that he did not want to be crippled. A referee was appointed and the five minute rounds were timed. The fight went off a little after midnight with odds two to one in favor of the more experienced McWilliams.

The first round was dancing and dodging, with no effective strikes landed. In the second, kick's were exchanged which drew blood, and both fighters went down in a tangle. McWilliam's seconds claimed foul because of the grappling, but the referee refused to call a foul. Over the next four rounds Tavish abused McWilliams legs so much that they had to be washed in vinegar to stop the bleeding,. Despite the bleeding, McWilliams was still fresh and Tavish was beginning to tire. After seven more rounds, the floor was sprinkled in Tavishs' blood.

Tavish had a short rally in the fifteenth, but by the end of the twenty-second round, Tavish's second couldn't stop the flow of blood and requested the legs be bandaged. The referee refused, and after Tavish was kicked for the fifth time in the twenty-third, he dropped like a log and refused to go on. Similar to the Davis match, Tavish would have given up at the end of the fourteenth if it hadn't been for the jeers of his backers. The fight ended around two a.m. and both had their legs washed in applejack. Tavish had to be carried away to the ferry, and before he and McWilliams reached Philadelphia, their legs, "covered in cuts and raw as beefsteak" as the quote at the beginning of this essay put it, had swollen out of all proportions.

From the cries of "foul" by McWilliams supporters when he was grabbed by Tavish, it appears that grappling was not allowed in this match. That would make sense, considering that the rounds were timed. Untimed rounds and no grappling would make for a long, brutal match. Notice also that some form of rotten apple or apple liquor was applied in more than one of these matches as a remedy for the pain and inflammation. Interestingly, this same advice appeared in Parkyns' Cornish wrestling treatise over 150 years earlier as a remedy for black eyes.

Today

By around 1900, purring appears to have died out as a living tradition. Louie Pastore, on the Western Martial Arts list, has written that close cousins of purring may have passed on in certain British children's games, known variously as "shinning," "cutlegs," "cutlegging," and more recently, "stampers," where the object is to stomp on the opponent's feet.

The Cotswold Olimpicks, which died out in the mid 19th century, was reintroduced in 1951. As a result, shin-kicking was also recently resurrected as an exhibition, and there appears to be an annual contest held at Cotswold, although the pool of participants seems to be quite small. J.R. Daeschner, a recent competitor, reported that the year he competed (likely 2003), there were a total of eight contestants, double the number of the year before. Rules seem traditional, in that they allow the competitors to stuff straw into their pants, allow grappling, and the best two of three falls wins the match, which is single elimination. See www.truebrits.tv/shin_kicking.html for an excerpt of Daeschner's account.

Purring, assumedly one of the "manly diversions" mentioned in the handbills for the early Cotswold Olimpicks, was a folk sport likely engaged in for the reasons such activities are normally pursued. It was recreation, to be sure, but it was also a pursuit of peer status, for it was unquestionably a test of a man's mettle and could give a man a reputation among his fellows. Another aspect was undoubtedly the desire to catch the attentions of the female spectators, for, as Parkyns put it, at most events there was that "small party of young women, who come not thither to choose a coward, but the daring, healthy, and robust persons, fit to raise an offspring from."

The Cotswold Olimpicks lasted, on and off, until the middle of the 19th century, but how long and how well purring remained an activity there is unclear. What is clear is that there were analogous wrestling practices that carried the same type of activity on from the 1600s. First Norfolk and then Devonshire wrestling had purring aspects, then as it disappeared from Devonshire wrestling, it had a last hurrah of its own in America when brought over by Cornish miners in the 19th century. Nowadays, the sport will likely be lost as a participant sport due to its brutal nature, but it may live on in exhibitions and demonstrations as expressions of cultural heritage.

Jason Couch

Original essay, 2004

References

Cotswold Olimpicks

www.rootsweb.com/~engcots/CotsOlym.html

www.stratford-upon-avon.co.uk/ccolymp.htm

Davis-Proudfit Match

National Police Gazette, November 1, 1879.

Grabby-McTevish Match

Truman, Major Ben C. Duelling in America. Joseph Tabler Books, San Diego, 1992; originally reported in the New York Sunday Mercury, 1883.

Tavish-McWilliams Match

Colorado Springs Daily Gazette, January 13, 1883.

Chester Times (PA), January 13, 1883.

National Police Gazette, February 3, 1883.

New York Times, January 13, 1883.

Bibliography

Carew, Richard. The Survey of Cornwall, 1602. See www.gutenberg.net/etext/9878.

Conroy, Tom. "Notes on Early English and American Wrestling History," Hoplos, 3:4, August, 1981.

Layton, Charles. Whole Art of Norfolk Wrestling (undated). See www.the-exiles.org/manual/norfwres/norfwres.htm.

Muldoon, Prof. James. Professor Muldoon's Wrestling, Street & Smith: NY, 1891.

Parkyns, Sir Thomas. Progymnasmata: The Inn-Play, or Cornish Hugg-Wrestler. 3rd ed., 1727. For Parkyns' wrestling and boxing technique sections, see www.geocities.com/Athens/Acropolis/4933/westernartsparkyns.html.

Pollock, Armstrong, et. al., Fencing, Boxing, and Wrestling, London, 1890.

Truman, Major Ben C. Duelling in America. Joseph Tabler Books, San Diego, 1992.

Walker, Donald. Defensive Exercises. 1840. For Walker's wrestling, see www.geocities.com/cinaet/walker.html; other sections are available elsewhere online.

White, W. A Londoner's Walk to the Land's End (1855), in A First Cornish Anthology, Tor Mark Press, Great Britain (1969).

Wylde, Zachary. English Master of Defence (1711). For Wylde's wrestling techniques, see www.geocities.com/cinaet/wylde.html; for the complete manual, see www.the-exiles.org/Manual%20Zach%20Wylde.htm.

In 1612, attorney Robert Dover started the "Cotswold Olimpicks," an annual fair full of pageantry and spectacle. Medieval fairs were mainly about commerce: held seasonally or annually, merchants traveled to exchange wares while laborers attended to display themselves to prospective employers. Entertainment was subsidiary to the commercial purpose. Dover's Cotswold fair was just the opposite, primarily a celebration of sport and competition, with the headline events being contests such as singlestick, wrestling, jumping in sacks, dancing, and shin kicking. The link below shows a 1636 woodcut of the Cotswold Games. The Cotswold cut shows the emphasis upon sport and recreation, while surviving Thames Frost fair souvenir cuts from 1683 show the center thoroughfare given over to mercantile pursuits. The rider on the horse in the Cotswold cut is assumedly Robert Dover, who liked to appear on horseback wearing clothing formerly owned by James I, obtained for Dover by a servant to the king. http://www.stratford-upon-avon.co.uk/ccolymp.htm

In 1612, attorney Robert Dover started the "Cotswold Olimpicks," an annual fair full of pageantry and spectacle. Medieval fairs were mainly about commerce: held seasonally or annually, merchants traveled to exchange wares while laborers attended to display themselves to prospective employers. Entertainment was subsidiary to the commercial purpose. Dover's Cotswold fair was just the opposite, primarily a celebration of sport and competition, with the headline events being contests such as singlestick, wrestling, jumping in sacks, dancing, and shin kicking. The link below shows a 1636 woodcut of the Cotswold Games. The Cotswold cut shows the emphasis upon sport and recreation, while surviving Thames Frost fair souvenir cuts from 1683 show the center thoroughfare given over to mercantile pursuits. The rider on the horse in the Cotswold cut is assumedly Robert Dover, who liked to appear on horseback wearing clothing formerly owned by James I, obtained for Dover by a servant to the king. http://www.stratford-upon-avon.co.uk/ccolymp.htm