Bobbing the head from right to left, "slipping," was known and practiced as early as 1733, for Bob Whitacker, we read, "slipped his head on one side of the big Venetian's long arm and gave him a severe blow in the stomach," which won him the fight. Hunt excelled in the habit of stepping backward or aside to avoid a blow. "Gentleman" Jackson brought "straight hitting" into prominence in 1795; and in 1804 Berks is reported to have "countered" a blow aimed at him by Pearce, the "Game Chicken," so heavily as to bring Pearce down on his knee. Counter hitting was probably practiced earlier than this, but is described as "jobbing," "meeting" and "fibbing." The modern boxer, like his ancestor, makes use of the parry, but instead of adding to the already numerous old guards (invariably led by the elbows and necessitating a change of position) he contents himself with two-made high or low, with the right or left hand, led by the hands and without changing position. He moves his head quickly in any direction and himself backward or forward with at least equal facility with his predecessors in the art, but with far more freedom and grace. Instead of swingers, back handers and choppers, a correct boxer drives his right or left in a straight line directly at the head or body, aggressively when he leads off, resistively when he counters. |

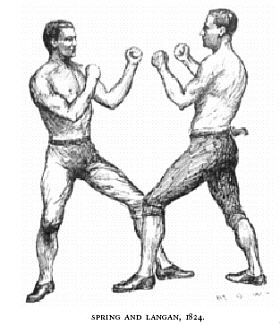

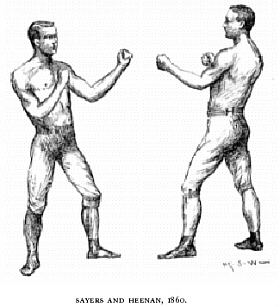

The improvement in the art has not been in the direction of the multitude of things to be done, but in the manner of doing them. The modern boxer poses in accordance with perfect physical deportment and moves with great ease, grace and freedom, which enables him to hit from a greater distance and with increased force, rapidity and precision. The three illustrations which we give depict the attitudes of the most accomplished pugilists at the commencement, near the middle and at the close of the period of seventy years ending 1860. It will be noticed that these attitudes range from bad to indifferent and from that to good form. All the accounts of the earliest recorded fights deal exclusively with the tricks by which the victor won, but later there is a change, and when Jackson fought in 1795 there is allusion to the excellence of his attitude, the ease and freedom of his movements and the straightness of his hitting. From this time forward more attention is paid to this important feature, until it becomes a criterion of good form. The loss of a fight is then attributed to the adversary's superiority in weight or the man's own lack of condition, or a chance blow, and trickery unaccompanied with ability is discredited. The kind of trickery practiced by clever curs-pugilists whose skill in seizing and making the most of every mean advantage is superior to their ability in actual fighting-is much to be condemned.  |