William Carleton

by John W. Hurley (Philadelphia: Xlibris Corporation, 2001) Paperback, 314 pages, annotations. 17 b&w illustrations. ISBN 1-4010-1981-1. $19.54

Order from www.Xlibris.com

Review by Tom Green

Irish Gangs and Stick-Fighting... is an anthology of two short stories and two novellas by Irish author William Carleton (1794-1869) with an introduction and numerous annotations by editor John Hurley. Though often overlooked by modern literary scholarship, Carleton (christened Liam O'Cathalain and the youngest of fourteen children of a small farmer in County Tyrone) is uniquely equipped to provide insights into Irish stick-fighting and the culture that created it.

This collection provides a wealth of information on fighting technique, stick (bata, shillelagh, or shilelah) construction, the range of weapons used by the fighters, codes of ethics among combatants, and occasions for combat. Hurley does not distill a simple set of instructions from Carleton's works, however. This material is embedded in 19th century fiction, and this fiction is long on "local color." The approach makes for a "thick" description of the Irish fighting tradition. In anthropological jargon, the idea of a thick description entails collecting as much about the context of an event as possible in an effort to understand not only "whats" and "hows", but "whys" and "whens" as well. In the case of the Irish stick-fighting tradition, an understanding of village feuding, the roots of religious conflict and the secret societies they breed, and the nature of local festivals and market days (prime occasions for gang fights) are necessary to round out the understanding of the martial art's infrastructure. Given the rarity of living sources of information, Carleton's sketches of 19th century Irish rural life may be as close as modern bata fighters ever get to studying in the old tradition (EN1). Just as learning the physical techniques of a martial tradition can hurt, absorbing the context of stick-fighting is not without its painful experiences. William Carleton's prose often is not easy to wade through-especially if your primary interest is practical martial arts technique. The understanding that results from the effort, however, and the rounding out of the tradition is worth the effort. I am convinced also that the editor has given us the most easily digested form of Carleton on stick-fighting, short of simply excerpting the "good parts." These are, after all, the stories that Carleton (himself a country shillelagh fighter) tells about these combats. Also, Hurley follows each of the narratives with extensive notes, translations, explanations of Gaelic Irish words, and discussions of Irish rural culture. These, along with his introduction, make the collection as user friendly as possible.

The anthology includes first-hand instructions on how to make a fighting stick (54) as well as describing traditional seasoning processes such as burying the weapons in dunghills or hanging them in chimneys (127-8). There is powerful evidence in the stories that Irish stick-fighting was not merely untutored banging away as well. There are extensive descriptions of combinations including methods of striking, targets and the use of feints (169ff.), the use of Celtic wrestling techniques (174), pugilism (293-295), and even women's combat tactics (63). Hurley emphasizes the systematic nature of Irish martial arts in a note describing striking tactics drawn from sword fencing (213). There is even support for the argument that distinct family systems existed in statements such as the following about Lam Laudher ('Strong Hand') O'Rorke, whose family was noted for bodily strength and fighting ability, "that was the Lam Laudher blow, my boy, an' what that is, is well known"(275).

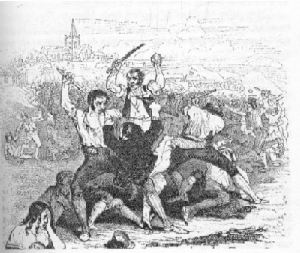

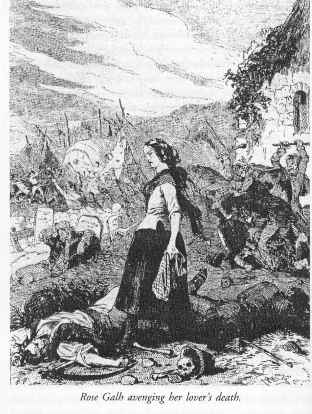

The volume is illustrated with the M.L. Flanery etchings and engravings taken from Carleton's original publications. The illustrations are instructive, if at times puzzling. On the instructive end of the spectrum are the illustration of "The Battle of the Factions" (cover and 27) which clearly shows the grip and forehand and backhand slashes with the bata and from the same story "Rose Galh avenging her lover's death" by means of a stone knotted in an apron consistent with existing descriptions of women joining faction fights using aprons or stockings weighted with stones.

More puzzling, however, are the recurrent illustrations of the bata as essentially straight clubs resembling billy clubs more than the knobbed sticks associated with the Irish tradition (see for example "The Battle of the Factions," 27 or "Kelly standing arms akimbo" 172). Readers are likely to be puzzled by the apparent discrepancies between Flanery's illustrations and violations of what has been assumed to be the norm and is in fact described in the narratives. For example, Carleton writes, "[R]eal Irish cudgels...should not be too long-three feet and a few inches is an accommodating length. They must be naturally top-heavy, and have...three or four natural lumps" (54).

Hurley obviously draws on a wide range of sources for his biographical, cultural and linguistic notes. I would like to explore some of them on my own, and I'm sure this is the case for other readers, as well. Unfortunately, these sources are not given. In a private communication, the author recommended Conrad Arensberg's classic The Irish Countryman: An Anthropological Study. I would go on to suggest other works that supplement and reinforce Hurley's points: Arensberg and Solon T. Kimball, Family and Community in Ireland, Henry Glassie, All Silver and No Brass, Peig Sayers (trans., Seamus Ennis) An Old Woman's Reflections, and Seán Ó Súilleabhain, various works, but especially Irish Folk Custom and Belief. But this is a minor quibble. John Hurley has performed an important service to the Western martial arts community and students of stick-fighting in particular by assembling this collection of William Carleton's sketches of 19th century Irish life that focus on the feud, Faction and Party fighting, and the tactics and weapons used therein (EN2). The book is a contribution in its own right, and it points toward some useful directions for future research. Many people involved in the western arts are required to flesh out the practice of physical technique with healthy doses on research in order to revitalize combative arts that were rendered obsolete by gunpowder and the legal system. While the historical swordsmen have been able to turn to the combat primers compiled by the masters of defense over a 700 year period and an extensive elite art tradition focused on Medieval and Renaissance fighting arts, students of Celtic stick-fighting have not enjoyed similar resources. That community's resources have been confined primarily to oral transmission obtained from elusive sources and bandied about on the E-lists, limited historical accounts, and occasional references to fighting arts in the mythology. These sources are shaky at best and require considerable interpretation and extrapolation. On the other hand, works of fiction have received comparatively little attention by the martial arts revivalists. Whatever our reasons for giving fiction short shrift, Hurley's anthology of Carleton's fiction should cause us to rethink our position.

EN1 - for further information on reconstructed Irish stick fighting, see http://www.geocities.com/Athens/Acropolis/4933/shillelagh.html

EN2 - on the Irish faction fighting tradition, see Carolyn Conley, The Agreeable Recreation of Fighting

Further Reading: Irish Gangs and Stick-Fighting In the Works of William Carleton by John W. Hurley