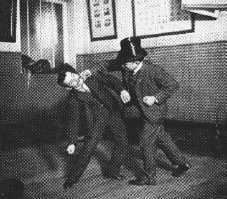

Savate, circa 1896

By Robert W. Smith

From Judo, II:9 (July 1958), 36-38; Judo, II:10 (August 1958), 16-17; Judo, II:11 (September 1958), 5-7. Copyright © 2001 Robert W. Smith. All rights reserved. Reprinted by permission.

La Boxe Française is a profound science which requires much composure, calculation and strength, It is the very best development of human vigor; a contest without other than natural arms in those circumstances in which one should never be taken unawares.- Theophile Gautier

The poet Gautier, who lived during the zenith of French boxing's popularity, has stated the case fairly. French boxing, although no longer popular, is a total sport. It requires some qualities from its learners but gives many more. The only school existing in recent times that I know of was being conducted in 1947 by Guillemin, former world champion in the sport and even then on the wrong side of 80. Guillemin calls French boxing "Fencing with Four Limbs" and states that it stresses speed, balance, dexterity, an appreciation of distances, and intelligence. Nearly all these qualities - plus mirth, which is priceless - are evident in a film I possess in which the old master cavorts like a 21-year-old. The success of judo, karate, and aikido in France since the end of World War II, however, suggests that French boxing will never regain the popularity it possessed in the middle of the 19th century.

If the eclipse deepens, as seems likely, it will be a pity. For French boxing has much to recommend it - as I hope to show. It is dramatic, highly competitive and like fencing, has romantic associations. Years ago I heard the story of a young beer-drinking Frenchman seated on a stool in San Francisco tavern. Many of you readers have doubtless heard the same tale. Because he looked "different," the Frenchman was approached and loudly insulted by a gargantuan chap with shoulders so wide that he had to come into the tavern sideways. The huge one was burning from the effects of firewater and obviously wanted to spread the conflagration. The Frenchman, young in years with facial features all pink and white, minded not the boisterous insults, until repetition reduced their niceties to mere cacophony. This apparently hurt the artistic soul of the Frenchman for he swung around on the stool to face his antagonist. Still holding a mug half-full of beer, he put his other hand in his pocket. The rough went into action instanter.

He threw a right fist as big as a small rosebush, which would have demolished a shed, had it landed. Luckily for our story, it did not. Coincident with the miss, the legs of the Frenchman lashed out, the feet snapped up and quicker than the eye could follow, ten or more kicks hit the house that walked like a man. That worthy immediately died for awhile. Then it was noticed that the youngster still sat atop the stool, one hand in his pocket, and the other holding the beer mug, from which not a drop had spilled - for it was still half-full. The Frenchman spun back around to the bar and resumed his drinking with some gusto.

This legend has gone around the globe and everyone retelling it swears he witnessed it at that San Francisco tavern. In a small Midwestern town in 1943 I heard the story from two different persons. The number of these witnesses makes it seem that the encounter took place in a stadium rather than a tavern. However, the significant thing about the legend is that - like all legends - it is true. Somewhere, sometime, something like the legend happened, though its details have been embellished since.

Another story comes to mind. Hollywood's The Great John L. (1945) had a scene in which John L. Sullivan (bowdlerized to "I can lick any man living") met a la boxe artist in a mixed match. John L. didn't realize that the French fought any different than Americans or British. So the Frenchman danced around the bigger American early in the fight and thoroughly confounded him with his lightning-like kicks. Just as sure as Tom Mix made it back to save the ranch, however, the American ultimately got in his punch, which upended the man from Gaul. I have checked every available reference work on John L. and have been unable to find this incident as fact. I must conclude that it is an invention of a scriptwriter, a thing not unheard of in Hollywood.

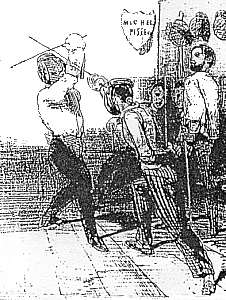

The history of French boxing is replete with interest. About the year 1830 it developed from savate, or foot boxing, a vicious type of fighting used chiefly by ruffians in which the feet were used almost exclusively as attacking members. In savate the guard was held low, the hands open and frontal, and blows were never delivered with the fist. Instead, the open palm was used to slap the face of the antagonist. Savate men used chiefly the low kick and did not exploit the chest and side kicks. Lessons were given primarily by disreputable teachers in the Paris slums. One of the foremost teachers, Michel Pisseux (1797-1863), [EN1] was described in this way by a writer of the period:

He was 36 years old; his face was full and marked by pox, his grey eyes full of trickery; his limbs were long and bony; his big hands, his knotted fingers seemed to have the solidity of wood; his rapid and disjointed gestures recalled the movements of old semaphore. He wore a short jacket, of the type worn by waiters, long trousers of brown cloth, and a cap from which hung on one side an enormous tassel.

Pisseux, the "terror of la Courtille," catered to a higher-class clientele than did most of his compatriots. The Duke d'Orleans and Lord Seymour were among his students. Soon savate came to vogue with men of a higher class. Taught in the back rooms of wine merchants in the slums, men of fashion armed themselves in this wise and flocked forth to do foot battle with the ruffians. The ensuing skirmishes must have made the Paris of that period a lively city. [EN2]

The necessity for gentlemen to arm themselves in this manner required that fit premises for them be provided and that men of discrimination take up the teaching of the art. Enter Charles Lecour (1808-1894), father of French boxing, whom Alexander Dumas (the father) called a genius. Lecour studied savate from an early age and became a proficient master of it by the time he was 20. Lecour went to England and studied boxing under Adams and Smith, two of the best pugilists of the period. On his return to Paris in 1832 he successfully blended French savate with English boxing to make French boxing. What had once been an incomplete art since only the legs were used was made complete, Lecour felt, by incorporating the use of the arms.

Shortly after the opening of Lecour's gym, two provincial teachers, Loze (from Toulouse) and Leboucher (from Rouen), arrived in Paris. Both had developed methods similar to Lecour's; the guard was raised, the hands clenched, and kicks delivered to chest level. Around this nucleus of fine instructors developed a great number of boxers who gave superiority to the Paris school. About the same time in the south, savate had given birth to a sport called chausson or jeu Marseillais, practiced chiefly in the military. The Marseillais method featured blows with the fist and higher kicks than savate, but was deficient in that the adversaries seldom faced each other and most of the kicks missed due to a lack of spatial orientation on the part of exponents. "Before a serious systematic sport," Charlemont says in his splendid text, "the Marseillais school could not hold up; it is, if one wishes, for gymnastics, for the dance, for clowning, but it is not for combat and for defense." [EN3]

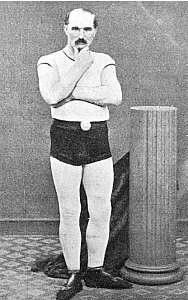

The greatest period in French boxing was the decade 1845 to 1855. Charles Lecour and his brother, Hubert, organized public matches at the Cirque [a music hall] as did Leboucher at the Montesquieu Hall. Hubert Lecour was small and used his fists and his feet with lightning rapidity. In this golden decade other players of great skill stood out: Curel, a southerner, lithe and nimble as a monkey; Tessier, cool and unemotional, forever dangerous; as well as Ducros, Rambaud, and the powerful Vigneron, who was known as L'Homme-Canon, after his trick of hoisting a 600-pound cannon to his shoulder.

Charles Ducros was a painting contractor by day and taught boxing at night. Of all the French boxers, he was the only one who could fight publicly in the English style, so skilled was he. In a match with Vigneron, he got his fists into the powerful one's face. Leboucher, who was refereeing, called out: "You were touched, you swerved to give notice of the blow, Mr. Vigneron." "You," replied Vigneron, "I return 18 to 20 to you!" "I know well," countered Leboucher with a voice like an enchanting bell, "because you have great legs." Ducros and Vigneron finished by embracing to the plaudits of the crowd.

Until Louis Vigneron appeared, the favorite of the crowds was the baker Rambaud, who appeared under the bizarre name of La Resistance. Big, muscular, handsome, blending size with grace, Rambaud was challenged by the newcomer Vigneron. The first bout ended with a draw and, in the second, Vigneron beat Rambaud completely.

Vigneron was a truly powerful man. He was not as fast as Lecour, Ducros and Charlemont, but his followers argued that because of his extraordinary strength he had to "pull" his punches, and this impeded his speed which was greater than it appeared.

In 1856 the French police banned wrestling and interfered with boxing. [EN4] Montesquieu Hall was made into a restaurant and the vogue of boxing diminished. Leboucher stopped promoting bouts and most of the boxing activity was relegated to instruction in small gyms. In 1862 Vigneron once again announced a public match. Prior to the match a young soldier approached him and asked to enter the lists. This was Joseph Charlemont, destined to be perhaps the finest master of them all. Vigneron said, "Here are the gloves, let me see what you know." After a few passes, Vigneron said, "That will do, but you must come to work out with me every day." After Charlemont asked, "And I will box at your match?" the conversation went as follows. "You will box." "With whom?" "With me." Vigneron had his hands full with this raw novice and before a year was out Charlemont was among the best boxers in France.

In 1866 Charlemont was matched with the speedy Hubert Lecour. At the outset Lecour scored three times in a row with the low foot kick. Charlemont did not lose his head but instead modified his method and had the advantage in the second half of the bout. Charlemont's reputation soared. He organized boxing and la canne (art of fighting with a cane) in the military and on retirement opened a gym. [EN5] Charlemont's text, La Boxe Française, Traité Théorique et Pratique (1877), is the classic work in the field. The work is a synthesis of the teaching of Vigneron, Lecour and others. It is a complete system of personal defense and is worthy of study even now, over three-quarters of a century after it was first published. Correcting and completing the work of his colleagues, his system embodies English boxing exercises, body kicks and blows, as well as wrestling movements.

Charlemont believed that a boxer must have four qualities, viz., ability to anticipate, composure, agility, and adroitness. The first two are innate but the latter two can be acquired by practice.

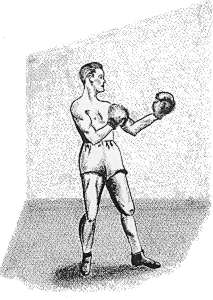

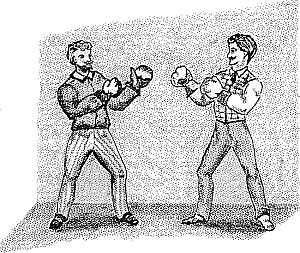

In a match the boxers wear regulation boxing gloves, which were much lighter earlier, and cloth shoes.

Basically there are two guard postures, right and left, not at all dissimilar from aikido and karate postures. I will describe in some detail the left guard posture. The reader will realize that the right guard posture is the same position led by the right, rather than the left side of the body.

To assume the left guard, take your right foot about 18 inches to the rear. Execute a half turn to the right. The toes of your left foot should now be directed towards your opponent, and those of your right foot to your right. Your heels should be on the same line. Your left leg should be straight without stiffness and your right leg slightly bent. Your weight rests on both legs with slightly more resting on the rear than on the front foot (say a 60-40 ratio in favor of the rear foot). Your body is held erect and your eyes should look directly at the opponent. Your left arm in front is half bent, the left fist at chin level, nails turned toward your face. Your right arm has its elbow at the body, closed fist level with your left breast and slightly apart from the body. Your fingernails should be turned toward your chest and your right shoulder thrown back slightly.

From these positions eight principal blows with the hands or feet are delivered in the form of leads, combinations, feints or counters. Spatial orientation is important. A proficient boxer is able to ascertain to the nearest inch the distance that separates him from his adversary.

As in judo, the spectacular trick is seldom the most rational. The most serious foot blows are those not going higher than the chest. The sensational high foot blows are dangerous for, if they miss, then the user's center of gravity is displaced, surrendering him to the counter of his opponent.

A major weakness of French boxing is a functional one concerned with the basic guards. No provision is made for a person off guard. Both players must have the same guard. If one is standing in right guard and the other in left guard, they are considered "wrongly on guard." To extend this to a street situation, if a man in right guard attacks you while you are in left guard you may be in difficulty since you haven't been trained in fighting in mixed positions. On this score aikido and karate are a good deal more functional.

One of the leaders in French judo circles wrote me nearly a decade ago that French boxing was superior, in his mind, to karate. Since then, he has become one of the leaders in the importation of karate into France and, learning more about karate, he has, I believe - though tact forbids my asking - revised his opinion. In my study of both, I must categorically give the palm to karate. Karate is superior to French boxing in that attacking members hardened; more members are used (head, elbow, knee, etc.); and movements are less circular and utilize the entire body, not merely a leg or arm divorced from the body. In short, I think that the mechanism of the body is more efficiently powerful, and speedily sewed in karate than in French boxing. [EN6]

This is not to minimize the latter, however. "Fencing with Four Limbs" is the best method of self-defense to come out of Europe. Men like Lecour, Vigneron and Charlemont were out of the same substance as the leaders of Kodokan at the turn of the century.

Gilbey, John F. (pseud. Robert W. Smith) Secret Fighting Arts of the World (Rutland, VT: Charles E. Tuttle, 1963)

-----. The Way of a Warrior (Richmond, CA: North Atlantic Books, 1992)

The editors wish to acknowledge the assistance of Guy Grunbaum in preparing these notes.

EN1. Pisseux was a nickname; the man's real name was Michel Casseux. According to a pamphlet he published in 1824, offensive techniques included front, round, and side kicks to the knee, shin, and instep, and palm-heel strikes (le coup de la musette) to the face and eyes. Defensively, hands were kept low to protect groins. Weapons included cane, stick, and flail.

EN2. In 1831, Casseux won a fight seen by the Count Alton-Shée, and this led to his system becoming patronized by French aristocrats. His academy was in the Parisian district of Courtille, and according to legend, his high kicks influenced the development of the cancan.

EN3. The reason was a spate of crudely fixed matches.

EN4. Prohibited techniques in chausson included headbutts; strikes with knee, elbow, and palm; and throws.

EN5. For pictures of Charlemont's cane methods, see http://ejmas.com/jnc/jncart_Charlemont_1200.htm.

EN6. Smith subsequently changed his mind on this analysis. To wit: "Functionally, aiki just is not a proven article. Even in practice, it has too many moves before a result is achieved. Karate in theory is as he [Robert W. Smith] describes it - a total body response but, again, it has yet to be translated to street use. As Funakoshi himself warned, it must have utility or it remains a dance. The question is moot, finally. But if I had to choose between Vigneron and Oyama to slum with in gay old Paree, I'd opt for the Frenchman." Way of a Warrior, 1992, page 88.