Edward William Barton-Wright

By Graham Noble

Copyright © 2001 Graham Noble. All rights reserved. Originally published in Journal of Asian Martial Arts, 8:2 (1999), 50-61. Reprinted courtesy Graham Noble. The author wishes to thank Richard Bowen, Harry Cook, John Sparkes, and Joseph Svinth for their assistance and use of materials from their personal collections.

Richard Gordon Smith, an Englishman living in Japan at the beginning of the twentieth century, made a note in his diary about a demonstration of martial arts he had witnessed:

Saw an interesting assault of arms today given by Mr. Uchida, Chief of the Prefectural Police. The jujitsu is so fast, in fact, that it is impossible to see what is done. A remarkable show of throws was given by Mr. Sato of Kyoto and Mr. Tanabe of Himeji, in which the latter was attacked allowing himself to be used as an example of what Mr. Sato could do - and in consequence was thrown about anyhow. The same two gave examples of choking tricks which were rather ghastly and were kept more or less secret - they would not have been shown here had it been a police exhibition. It appeared to me to be simpler to kill a man by stopping the flow of blood than by the passage of air. Another interesting competition was girls versus men; the latter with double-handed swords made of bamboo and the former with the long spear-like weapon known as naginata, which ladies and others used to carry. They simply cut the men's legs from under them with their side swipes.Smith found the demonstration an interesting diversion, but he had no real interest in the arts of personal combat, and he left it at that. But to Edward William Barton-Wright, an English engineer living in Japan in the 1890s, things were different.Perhaps one of the most notable things about the whole entertainment was the extraordinary silence. Not a sound of applause came at any time except from an agent of the P and O [steamship line], who, with the exception of myself, was the only foreigner present. Also most creditable was the absence of jealousy, personal feeling, one might also say, of rivalry, had the fights not been so real. Etiquette runs from the back of the heel to the tip of the sword, as it were. All personal feeling must be completely suppressed - not even a smile.... Jujitsu is hardly the thing for Englishmen - we are much too interested in finding the winner. (Manthorpe, 1986, 213)

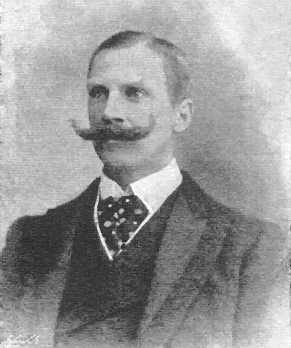

Edward William Barton-Wright

Barton-Wright was born in India to a Scottish mother and Northumbrian father in November 1860. After completing his education in Germany and France, he set out around the world, operating mining concessions in Spain and Portugal before moving on to Egypt, Japan, and the Straits Settlements. Many years later he told Gunji Koizumi: "I have always been interested in the arts of self-defence and I learned various methods including boxing, wrestling, fencing, savate and the use of the stiletto under recognised masters, and by engaging toughs I trained myself until I was satisfied in practical application." (Koizumi, 1950).

So when Barton-Wright came into contact with jujutsu it must have fascinated him. In his three years stay in Japan he studied the art under an unnamed sensei "who specialised in the kata form of instruction," and then took lessons at the school of Jigoro Kano, although he admitted that he had not been taught "the higher forms of the art." (Koizumi, 1950). When he returned to England and set up a martial arts school, he wrote to contacts in Japan asking for Japanese experts to be sent to England. Yukio Tani and Sadakazu Uyenishi were sent, and became the two pioneers of jujutsu and judo in England.

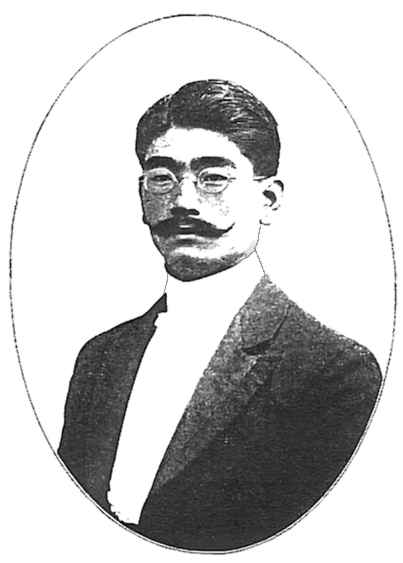

Sadakazu Uyenishi

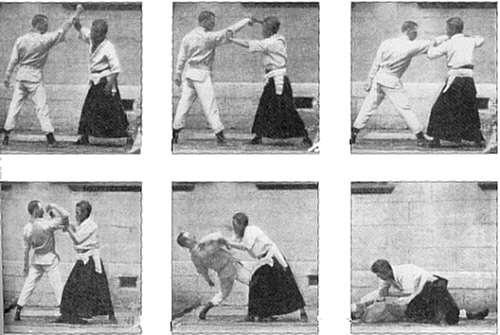

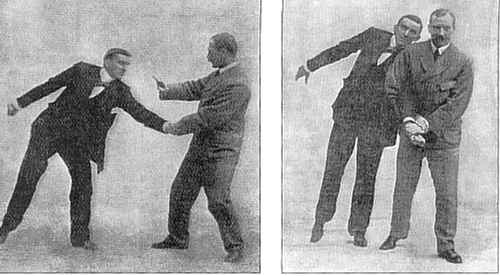

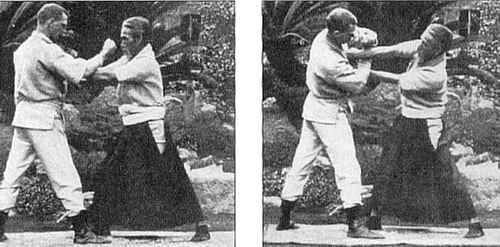

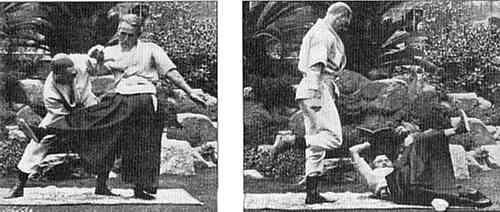

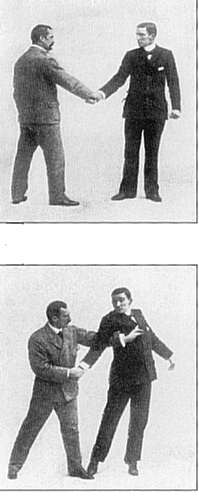

In March 1899, over a year before Tani's arrival, Barton-Wright had an article published in Pearson's Magazine under the title "The New Art of Self Defence" (1899:269). The principles of this new art he summed up as:

In essence, he was describing jujutsu. Although he did not name the art, there were numerous photos of him demonstrating its techniques with a Japanese "wrestler" dressed in hakama. (It is not known what style of jujutsu is represented in these photographs.) To the modern eye the techniques look ordinary, but a hundred years ago this really did seem like something new and Barton-Wright's demonstrations often made quite an impact. An editorial note to the article is worth quoting in full with slight paraphrasing:

Mr. E.W. Barton-Wright, the author of this article... has just introduced into this country a system of self-defence which would seem to render anyone acquainted with it practically impregnable against all forms of attack, however dangerous and unexpected they may be.Sometimes, of course, enthusiasm bred overconfidence and this was helped along by Barton-Wright himself. He wrote, for example, that "a man who attacks you with a knife or other weapon can be easily disarmed," adding that "the 300 different throws, attacks, counters and tricks based on leverage and balance" constituted "a class of self-defence designed to meet every possible kind of attack, whether armed or otherwise" (Barton-Wright, 1899:269)It is possible however, that after a consideration of the explanations which follow, many persons will exclaim, 'This is all very well on paper but in practice it will possibly be otherwise.' We must confess that when Mr. Barton-Wright first came into this office with his credentials and claims (a short, good looking man with no indications of unusual strength) we ourselves were somewhat sceptical, but a few practical tests soon showed that we were in grievous error! Others too have scoffed at first - professional strong men, gymnasts and athletes generally - but not one of these has met Mr. Barton-Wright and put him to the test who has not in the end been bound to admit that his system is irresistible.

His extraordinary resource in meeting every imaginable kind of attack was exemplified in a most remarkable manner at a performance we witnessed a few weeks ago. On this occasion, Mr. Chipchase, the amateur champion of the Cumberland and Westmorland style of wrestling, made many attempts to overcome Mr. Barton-Wright's defence, all of which were unsuccessful. By way of experiment Mr. Chipchase was allowed to seize him by one leg to prove whether, with this advantage, he could tip him over backwards. But incredible as it may seem, Mr. Barton-Wright, apparently without the slightest exertion, threw his opponent and disengaged himself.

Then he stood with both feet together and allowed Mr. Chipchase to seize him by both his ankles. In spite, however, of this handicap, Mr. Barton-Wright succeeded in extricating himself and throwing his opponent instantaneously. He then allowed himself to be seized from behind, with his arms pinioned to his side, but again he threw his opponent once upon his back.

Perhaps his most remarkable feat was to allow the amateur champion, standing with his back to him, to reach over his shoulders and seize him by the neck and head, and with this hold throw him right over his head. But whilst in the air Mr. Barton-Wright grasped Mr. Chipchase in some way, which owing to the speed with which it was performed, it was impossible for the eye to follow, and although apparently thrown himself, he had, by the time he reached the ground, thrown his opponent and was kneeling over him. Many other feats, just as extraordinary and just as conclusive, were also performed on this occasion, apparently without effort.

Extraordinary interest has been advanced in this new art of self-defence by the privileged few who have already had the opportunity of forming an opinion as to its efficacy. Colonel C.W. Fox, for instance, the Assistant Adjutant-General of the York District and ex-inspector of General of Army Gymnasia writes: 'I have no hesitation in pronouncing Mr. Barton-Wright's system as absolutely sound in theory, exceedingly practical and very scientific. I was much impressed with the extremely easy and graceful way in which he seemed to disturb the balance of his opponent and render him helpless. And although Mr. Barton-Wright repeatedly allowed his opponent to choose his own hold and take him at the greatest possible disadvantage, he never seemed to be at a loss what to do, and how to throw his opponent instantaneously. I am quite certain that if our police were to learn some of his throws and grips, they would cope much more successfully with every kind of resistance.'

Mr. Chipchase's opinion as an expert may not be uninteresting. He says: 'In spite of my being a much heavier man than Mr. Barton-Wright, his system of defence and retaliation is so much more scientific than my style, that when practising with him, however great may be my determination to remain firm on my legs and to keep my balance, my efforts are invariably frustrated, and I am ignominiously thrown. Mere strength has no chance of withstanding the science of this new art.' (Barton-Wright, 1899:268)

W.T.A. Beare, writing on various methods of "Antagonistics" (an old word for self-defence methods) gave credit to Barton-Wright's system but struck a note of realism:

I cannot accept Mr. Barton-Wright's system, valuable as it may be, as a royal road to invulnerability, nor can I imagine that he is himself invincible... I should very much like to see a bout in real earnest between Mr. Barton-Wright and some lightweight expert in boxing and wrestling, English style. I am not too strongly inclined to prophesy that the English style would prevail right away; indeed I doubt if it would. There is so large an element of trickiness about the Japanese method that the English expert might well be caught unawares.Beare also wondered about whether some of Barton-Wright's methods were "fair." Indeed, he thought, many of them could be classed as "absolute fouls." That was the fine old English sense of fair play, although he did recognise the value of the art in the street. "All who witnessed Mr. Barton-Wright's exhibition," he wrote, "must have been, as I was, greatly impressed by his agility and the effectiveness of his methods when employed upon a subject unfamiliar with them. Some of his catches and throws, for instance, are particularly valuable for use when attacked in the streets, and are calculated to upset the burliest of ruffians. The way too, in which he apparently gives the fall to his opponent, but finishes up 'top dog,' with the other at his mercy, is really quite wonderful, and one would be glad to become expert in such a method. It could not fail to be useful in cases of emergency" (Beare, 1901, n.p.).But what I do contend is that a really clever man would not be at a loss for long. There is one main underlying principle throughout Mr. Barton-Wright's system, and that is, broadly stated, application of unnatural strains to the limbs. My presumed clever performer would quickly become alive to this - not necessarily, as I have suggested, in the first meeting - and would refrain from affording his opponent facilities for his peculiar holds, which are easily possible so long as they are unexpected.

Barton-Wright referred to his system as "Bartitsu," although everyone was quite clear that what he was teaching was primarily Japanese methods of self-defence - jujutsu, or "Japanese style wrestling." Barton-Wright showed real enterprise in bringing Japanese experts to England and they were an essential part of his efforts to establish jujutsu in Britain. Barton-Wright liked to give demonstrations of technique, but whenever real grappling was called for - against a tough wrestler, maybe, who doubted the whole thing - it was the Japanese who went onto the mat.

Yukio Tani. Photo courtesy the Budokwai.

Yukio Tani and Sadakazu Uyenishi were the two young Japanese jujutsu

experts managed by Barton-Wright during their early professional exhibitions

in England. They taught at his martial arts school and gave numerous demonstrations.

William Bankier, who later became Tani's manager, wrote that these early

displays were often badly managed and gave little opportunity for the Japanese

to show their real worth, or test their skill against well known men. Presumably

Bankier may have had personal reasons for criticising Barton-Wright's management,

but as a matter of interest the report of the Bartitsu Tournament (December

1901 at the St. James's Hall) stated that the demonstration by Uyenishi

and Tani "was ingenious, certainly, but in the absence of any real contest

failed to carry conviction" (Sandow's, 1902: 29).

Jujutsu was the essential element of Barton-Wright's system, but actually,

his ideas went some way beyond that. In a talk given to the Japan Society

of London ("Ju-Jitsu and Judo," printed in the Transactions of the Society,

1902), he explained that his art of Bartitsu meant "real self-defence in

every form" and is interesting because he included boxing, wresting and

savate within the sphere of his art. As for jujutsu, Barton-Wright seemed

to have reached the conclusion that, like all other extant forms of personal

combat, it had certain shortcomings but should form an essential part of

any self-defence system. The minutes of his lecture state that:

Jujutsu was the essential element of Barton-Wright's system, but actually,

his ideas went some way beyond that. In a talk given to the Japan Society

of London ("Ju-Jitsu and Judo," printed in the Transactions of the Society,

1902), he explained that his art of Bartitsu meant "real self-defence in

every form" and is interesting because he included boxing, wresting and

savate within the sphere of his art. As for jujutsu, Barton-Wright seemed

to have reached the conclusion that, like all other extant forms of personal

combat, it had certain shortcomings but should form an essential part of

any self-defence system. The minutes of his lecture state that:

Under Bartitsu is included boxing, or the use of the fist as a hitting medium, the use of the feet both in an offensive and defensive sense, the use of the walking stick as a means of self-defence. Judo and jujitsu, which were secret styles of Japanese wrestling, he would call close play as applied to self-defence. In order to ensure as far as it was possible immunity against injury in cowardly attacks or quarrels, they must understand boxing in order to thoroughly appreciate the danger and rapidity of a well-directed blow, and the particular parts of the body which were scientifically attacked. The same, of course, applied to the use of the foot or the stick. Judo and jujitsu were not designed as primary means of attack and defence against a boxer or a man who kicks you, but were only to be used after coming to close quarters, and in order to get to close quarters it was absolutely necessary to understand boxing and the use of the foot. (Barton-Wright, 1902: 261)Barton-Wright was always ready to learn new methods to widen his teaching. He wrote a couple of well-illustrated articles on "self-defence with a walking stick" (January and February 1901), giving full credit for the system to "a Swiss Professor of Arms, M. Vigny." Vigny was actually Pierre Vigny, a teacher of la boxe française (French boxing, or savate as the English then usually called it) who had developed a comprehensive system of self-defence using a walking stick. He was featured in magazines of the time such as Health and Strength and later had his own martial arts school in London. Alfred Hutton also mentioned the Bartitsu Club as the headquarters of the ancient (i.e., Elizabethan) swordplay in England (Hutton, 1901: 128). Located in London's Shaftesbury Avenue, the club was visited by a Mary Nugent in 1901, for an article she was to write for Health and Strength magazine (Nugent, 1901: 337). She found "a huge subterranean hall, all glittering, white-tiled walls, and electric light, with 'champions' prowling around it like tigers."

Nugent interviewed Barton-Wright and seemed quite taken by his rather gruff manliness. He would have been 40 or 41 at the time, a man of the world. She was surprised by Barton-Wright's quickness when he explained some point or other ("it was electric"), and he told her that a couple years before he had been involved in a fight with two men in a Kentish country lane. He had been cycling to Margate when two roughs blocked his way. Jumping from his cycle, he drove his shoulder into the first man, laying him out. He knocked the second man down with a punch but broke his hand doing it.

Obviously, Barton-Wright must have had some degree of skill in his art, although there seems no real evidence that he was a strong contest fighter; according to an article by Ken Palmer (1988: 29), he was defeated in a 1906 contest with wrestler Andrew Newton. His true interests probably lay more in self-defence methods than in competition or sport. In the Pearson's article, Barton-Wright wrote: "I have repeatedly been attacked during a long residence in Portugal by men with knife or six-foot quarter-staff and have in all cases succeeded in disabling my adversary without being hurt myself, although I had not even a stick in my hand with which to defend myself" (Barton-Wright, 1899: 270).

Gunji Koizumi, who took an interest in the early history of British jujutsu and judo, once visited Barton-Wright, at the time a remarkably fit ninety-year-old. Koizumi's memoir of the meeting was published in the Budokwai quarterly Judo in July 1950. As he walked into Barton-Wright's house, Koizumi reported feeling as if he was stepping back to the Victorian age. Barton-Wright showed him an electrical device which he had invented and which he used to treat arthritis and rheumatism; a life-long interest apparently, since almost fifty years before he had told Mary Nugent about his new Chemical Light and Heat Ray Treatment. The old master of Bartitsu, who still retained his old self-regard, talked about his early days and recalled one occasion when he gave a demonstration at the St. James's Hall, a regular meeting place for sportsmen: "I challenged anyone to attack me in any form he cared to choose. I overcame seven in succession in three minutes. All were fourteen stone. Through this feat I received a Royal Command from King Edward the Seventh" (Koizumi, 1950:18). The Royal Command also features in the 1901 article by Mary Nugent. Barton-Wright told her that, at the time of his encounter with the two toughs, "He had a command performance hovering over him, the King (then Prince of Wales) having heard of his work, and being keenly desirous to see it" (Nugent, 1901:340). However, the broken hand resulting from the fight prevented him from giving the performance.

Barton-Wright also talked about Yukio Tani - how he had tried to teach him boxing ("the little Jap had no aptitude for the sport") (Koizumi, 1950:18) and how Tani had once defeated a sixteen stone (224 lb.) challenger in one minute, for a £100 bet. But also, he said, Tani had been difficult and had failed to keep appointments. An argument arose between the two men, and Tani threatened him. They fought and, according to Barton-Wright, "Bartitsu proved superior to Tani's jiujitsu" (Koizumi, 1950:19).

Well, I don't suppose anyone has ever believed that story, since William Barton-Wright was never in Tani's class as a martial artist. But he was the bigger and heavier man and if he had been able to land a surprise punch.... I don't put much credence in Barton-Wright's account, but I suppose it might have happened. Whatever the reason, Tani left Barton-Wright to work under the management of William Bankier, and during the jujutsu boom that followed Barton-Wright was left on the sidelines. He continued to teach, apparently into the 1920s, but the art of Bartitsu, for which he once held such high hopes, faded away and was soon forgotten.

Barton-Wright died in 1951, at 90 years of age and he was buried in an unmarked grave, "a pauper's grave," as Richard Bowen wrote, "as there was no money for a proper grave" (Richard Bowen, personal communication). A year or so before, he had attended the Budokawi's annual celebration at the Royal Albert Hall and had been presented to the audience. That was some kind of recognition, and it was only right, because in a way he had started the whole thing. He was the first to introduce jujutsu to England (I know about T. Shidachi's lecture to the Japan Society of London in 1892, but this was an isolated demonstration that never led to anything) and the first to bring in Japanese instructors. And he was also the first (that I know of, anyway) to try and bring together elements of different combat arts into a comprehensive self-defence system.

Unlike the Japanese, Barton-Wright was not tied exclusively to the traditions

of jujutsu. He was not a Japanese budoka but an Edwardian Englishman with

a practical frame of mind. In the February 1899 edition of Pearson's

Magazine he wrote an article on how to duplicate the feats of certain

stage "strongmen" (and women). As Barton-Wright explained, these were not

true feats of strength but more tricks of leverage and body mechanics,

something that might today be demonstrated before a gullible public as

feats of ki. As befitted an engineer, he had a good understanding

of body mechanics, and he saw an embodiment of such principles in jujutsu.

But in the overall search for combat effectiveness, jujutsu needed to be

augmented by other methods, notably boxing, wrestling, and savate (la

boxe française). In his attempt to make this synthesis, Barton-Wright

was the early ancestor of all the modern "eclectic" stylists who bring

together different forms to produce a new martial art. He was an interesting

and important character and he deserves his niche in martial arts history.

"The Bartitsu tournament." (1902, January). Sandow's Magazine, 28-31.

Barton-Wright, E.W. (1899, January). "How to pose as a strong man." Pearson's Magazine, 7, 59-66.

Barton-Wright, E.W. (1899, March). "The new art of self-defence: How a man may defend himself against every form of attack." Pearson's Magazine, 7, 268-275.

Barton-Wright, E.W. (1899, April). "The new art of self-defence." Pearson's Magazine, 7, 402-410.

Barton-Wright, E.W. (1901, January). "Self-defence with a walking stick." Pearson's Magazine, 11, 11-20. Reprinted at http://ejmas.com/jnc/jncart_barton-wright_0200.htm.

Barton-Wright, E.W. (1901, February). "Self-defence with a walking stick." Pearson's Magazine, 11, 130-139. reprinted at http://ejmas.com/jnc/jncart_barton-wright_0400.htm.

Barton-Wright, E.W. (1902). "Ju-jitsu and judo." Transactions of the Japan Society, 5, 261-264.

Beare, W. (1901, January). "Antagonistics." Sandow's Magazine.

Bowen, R. (1997). "Further lessons in Baritsu." The Ritual: Review of the Northern Musgraves Sherlock Holmes Society, 20, 22-26.

Hirayama, Y., and Hall, J. (1996). "Some knowledge of Baritsu: An investigation of the Japanese system of wrestling used by Sherlock Holmes." The Ritual: Review of the Northern Musgraves Sherlock Holmes Society.

Hutton, A (1901). The Sword and the Centuries. London: Grant Richards. Reprinted 1995, Barnes and Noble.

Kano, J. (1986). Kodokan Judo. Tokyo: Kodansha International.

Koizumi, G. (1950, July). "Facts and History." Judo: The Budokwai Quarterly Bulletin, 17-19.

Manthorpe, V. (Ed.). (1986). The Japan Diaries of Richard Gordon Smith. London: Viking/Rainbird.

Nugent, M. (1901, December). "Barton-Wright and his Japanese wrestlers." Health and Strength, 3(6), 336-341.

Noble, Graham. "The Odyssey of Yukio Tani," http://ejmas.com/jalt/jaltart_Noble_1000.htm.

Palmer, K. (1988). "Japanese ju-jutsu comes to Britain: A glimpse back to a bygone era." Fighting Arts International, 47, 28-35.