Text and images copyright Graham Noble © 1986, 2000. Annotations copyright Joseph Svinth © 2000. All rights reserved.

Ed. Note: This article first appeared

in Fighting Arts International, and is reprinted by permission of

Graham Noble. Noble says that while he has since collected more material

on Motobu, to include a copy of a recently reprinted Watashi-no-karate-jutsu,

"it is almost all in Japanese, so before I do any rewriting I need that

translated. Hopefully computer programmes will sort that out in a few years."

Some editorial annotation has therefore been added, and a couple of now

outdated paragraphs relating to boxer Piston Horiguchi have been deleted.

Readers with additional information are requested to contact the editor

at jsvinth@ejmas.com.

Choki Motobu in Japan

Motobu was born in Shuri, the old capital of Okinawa, in 1871. He had considerable local fame in Okinawa as a fighter-strongman but it was only after he moved to Osaka in 1921 that he became known in Japanese martial art circles.

What brought Motobu to the attention of the Japanese was his victory over a western boxer in a kind of all-comers challenge match. In the earlier part of this century such bouts were occasionally held in Japan pitting western boxers against judo or jujutsu men. (Karate was unknown in Japan around this time.) [EN1] These were not "official" bouts for any sort of legitimate title, but something more like sideshow attractions. Boxing historians for example are fond of pointing out that, back in 1928 in Yokohama, top bantamweight Packy O'Gatty KO'd a Japanese jujutsu man named Shimakado in 14 seconds. That 14 seconds included the full count, by the way. E.J. Harrison also mentioned in passing a couple of boxing vs. judo shows in his book The Fighting Spirit of Japan, first published in 1913. Few of the fighters in these events were champions in their sports, but the shows did arouse interest in a certain section of the populace.

Anyway, this was the background to Motobu's victory that so delighted the people back in Okinawa when they heard about it. Soon after Motobu settled in Japan he went to watch a boxing versus judo show in Kyoto. A boxer taking part beat several judo men rather easily and then issued an open challenge. Moreover, the challenge was issued in a boastful and derogatory way. Choki Motobu, who was sitting in the audience, stepped up onto the stage (or ring) and in the ensuing battle he knocked the boxer out -- probably with a punch, or series of punches, to the head. That is about as much as we can say about it since no contemporary reports of the fight exist. [EN2]

I knew that the Japanese magazine Kingu ("King") had published a story on Motobu and the boxer back in 1925, but when I finally tracked this down and read the translation, I found that it was a piece of imaginative, popular journalism rather than an accurate blow-by-blow report. However, the importance of this feature lay not in its accuracy as a fight report but in the publicity it gave to what had previously been an obscure event. Kingu was the major general interest magazine at the time with a circulation of over a million and this is how Motobu's exploits came to be widely reported. For the record, the Kingu story states that Motobu knocked the boxer unconscious with a rising palm heel strike. On the other hand, Seiyu Oyata, a modern day Okinawan karate expert, states that Motobu won the fight by kicking the boxer in the solar plexus and finishing him off with a strike to the neck. Shoshin Nagamine (Shorin-ryu) says that the knockout came in the third round from a strike to the temple. Motobu hit the boxer so hard that he was knocked out and blood came from his ears. Nagamine was told by Motobu that he had won a hundred yen by betting on himself. [EN3]

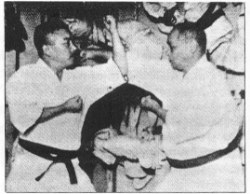

There is no doubt that Choki Motobu was a formidable fighter. Hironori Ohtsuka, the founder of Wado-ryu, knew Motobu in the 1930s and recalled that he was "definitely a very strong fighter." Ohtsuka remembered seeing a fight, or maybe it was more of a sparring match, between Motobu and a boxer named Piston Horiguchi. Motobu blocked the boxer's attacks and Horiguchi was unable to land a single clean punch. [EN4]

Choki Motobu was over 50 years old when he defeated the western boxer! People on Okinawa used to say that he liked to fight more than anything else, and certainly he did not seem to mind a good brawl. In 1932, when he was 60 years old, a group of expatriate Okinawans brought him to Hawaii to face the fighters there, presumably boxers and judomen. However, no bouts took place because the Hawaiian immigration authorities considered him an undesirable and he had to leave almost immediately.

Motobu was born into a high-ranking family at a time when education and privilege were reserved for the first-born son. Consequently, as a third son, he was rather neglected. His elder brothers, however (and particularly Choyu Motobu, the eldest) were good karateka and he may have learned something of the art from them.

As a young man, Choki Motobu's ambition was to become the strongest man in Okinawa. To fulfil this ambition he trained himself every day, lifting stone weights and hitting the makiwara (striking post). There are stories that he would hit the makiwara a thousand times a day, and even if this is an exaggeration it illustrates the importance he attached to this training drill. Nagamine recalls that Motobu would sometimes sleep outside, (when he slept inside the dojo he would lie on the hard wooden floor, without a mattress), and if he woke up during the night, rather than turning over and going back to sleep he would get up and hit the makiwara. Motobu was also very agile and quick and he got the nickname "Motobu-saru" (Monkey Motobu) not only because of his rough behaviour but also because of his remarkable agility in climbing trees and moving from branch to branch as nimbly as a monkey. In his youth at least he seems to have been a good natural athlete.

He was a good runner, too, and Japanese karate expert Hiroyasu Tamae writes of one occasion when Motobu was fighting attackers then ran off, jumped nimbly onto a roof and began tearing off the roofing tiles and throwing them at his assailants, beating them off in this way. Tamae makes the point that Okinawan roof tiles are secured very strongly to withstand typhoons, and it requires powerful hands and arms to tear them loose, but for a man reputed to be the best fighter on Okinawa it still seems a strange way to act. I guess Motobu's behaviour was just eccentric at times. Gichin Funakoshi used to say that he never knew what Motobu would get up to next.

One time when Choki Motobu was watching the bullfighters in Shuri he constantly blocked the view of the spectator behind him. The man became increasingly agitated and finally shouted at Motobu and struck him with a walking stick. Motobu turned, grabbed the stick from the man and struck him back across the head -- knocking him unconscious. He may not have intended this but he was rough and heavy-handed and probably didn't realise his own strength. After he knocked several of them down however the rest ran off. It was incidents such as this that gave rise to Motobu's other nickname of "teijikun" -- "real fighter". (This story is from Richard Kim's book Weaponless Warriors.)

Choki Motobu's idea of a good training session was to go down to Naha's entertainment district and pick fights. This area was well known for street fighting and Motobu picked up valuable experience in this way. Being bigger and stronger than the average Okinawan he usually won these fights but there was one occasion when he tackled a man called Itarashiki and was well beaten. This Itarashiki was a karate expert and the defeat only made Motobu more determined to train hard and learn more about karate.

At this time around the turn of the century karate was just beginning to emerge from generations of secrecy and the senior masters were sensitive about the image of their art. They looked upon karate as a physical art, building health, strength and character and they did not approve of Motobu's exploits in the rough areas of town. Nevertheless he was able to get instruction from several leading experts. (Seikichi Toguchi has said that because of Motobu's upper class birth, many karate masters found it difficult to refuse him instruction.) Motobu originally studied karate with the famous Ankoh Itosu (1830-1915), the leading master of Shuri-te. However he came to feel that he was not learning enough, and growing dissatisfied with Itosu's teaching he later studied with Tomari-te's Kosaku Matsumora (1829-1898) and with Master Sakuma. However, Motobu's karate always seemed to bear his own distinctive stamp, arising no doubt from his independent nature and his fighting experiences. He always emphasised practicality and in time many people came to regard him as the best fighter on Okinawa. True, he was beaten in a shiai (contest) by Kentsu Yabu (1866-1937), Itosu's senior student and a tough character, but we don't know the full circumstances surrounding this. Yabu was Choki Motobu's senior in karate by several years, and at the time of the contest Motobu may have been a comparative novice. [EN5] This is something that needs clarification; but anyway it is a fact that Motobu was famous in Okinawa for his fighting ability.

I first read about this colourful figure years ago in Peter Urban's book Karate Dojo. Although this has remained one of my favourite karate books, it has little value as a historical source and Urban describes Choki Motobu as a giant of 7 foot 4 inches "with hands and feet like monstrous hams" an early Okinawan version of the Incredible Hulk in fact, who was almost impossible to hurt and who "preferred to grab his enemies and chop them to death." A couple of years later the American karateman, Robert Trias, trying to inject a note of reality (?) into the subject, told an interviewer that the accounts of Motobu's size had been exaggerated and that actually he was "only 6 feet 8 inches" tall.

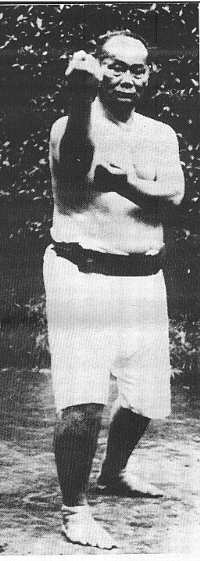

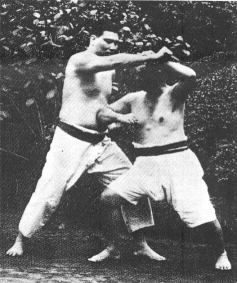

All this was rather hard to believe and at one time I wrote to Richard Kim, the famous authority on karate history, about it. He kindly replied, stating that Motobu was a little under 6 feet tall and solidly built, weighting around 200 lbs. This sounded reasonable, yet as I learned more about Choki Motobu I had to constantly revise the estimates of his height downwards. In fact the existing photographs, taken in the 1920s and 1930s, show him to be no bigger, and in some cases smaller, than his training partners. The article in the old Kingu magazine gives his height as 5 feet 3 or 4 inches and I would think this is correct. He was thus only a little bigger than other early pioneers of Japanese karate such as Funakoshi, Mabuni and Konishi, although of a much heavier build.

The photos we have of Motobu show him in middle age when he had put on weight and thickened appreciably round the waist. He had a sturdy, robust appearance but for a reputed strongman, the muscular development of his arms, chest and back does not look particularly impressive, at least by today's standards.

Another myth about Motobu is that he only knew one kata, the Naihanchin (Tekki in the Shotokan version). This is incorrect. He also knew Passai -- evidently there is a rarely seen Motobu version of this kata -- and Gojushiho, and although he may not have practiced them he was aware of the major kata of each style -- Shuri-te, Naha-te, and Tomari-te. (He provided a list of the major kata in his book.) It would be true to say, however, that he did become attached to Naihanchin, and for all the talk about him not being good at kata, the photographic record shows that technically his performance of Naihanchin was quite as good -- if not better -- than Gichin Funakoshi's.

Choki Motobu was not against kata but he did require that they relate to combat. In Naihanchin for instance his students were taught to pay attention to various technical points. It seems that the nami-ashi ("wave returning" foot movement) in Naihanchin was originally interpreted as a stamping movement to attack the opponent's leg (now it is usually taught as a foot block against a kick) and consequently many karateka would crash their foot down noisily on the floor while doing this technique. Motobu however, although he did the movement strongly with a kiai, always kept good balance and put his foot down lightly. It wasn't that his technique was weak, because he once broke an opponent's leg with this stamping waza (technique). He explained to his students however that if the technique was brought down with a big crash then you might find it difficult to maintain your defence throughout the movement. According to Yasuhiro Konishi, Motobu thought about every detail in the kata in this kind of way.

However, where Choki Motobu really differed from other leading karate masters such as Funakoshi, Mabuni and Miyagi was in basing his style on the study of kumite.

Kata seemed to occupy a secondary position with him. His karate stressed alertness, sharpness, and practicality, and his experience in brawls and street fights showed through in his techniques, which were straightforward and effective. Some of his kumite-waza were shown in his book Ryukyu Kempo Karate-jutsu. Kumite ("The Okinawan boxing art of karate-jutsu. Sparring techniques"), published in 1926. Incidentally, Motobu could not speak or write mainland Japanese at all well and it is thought that someone else must have written it under his direction, or possibly he dictated it. But at any rate the book's philosophy is his and he posed for all the illustrations.

Judging from this book, Motobu used a natural stance and it is noticeable that when blocking or striking he did not pull his other hand back to the hip (the action of hikite) but held it across his body as a guard, where it could be brought into action more readily. He also stressed training the weaker side of the body to bring it up to the natural side. For instance, in hitting the makiwara he recommended doing more repetitions with the weaker, left hand, if you were right handed. And he also frequently told his students to "Defend the centre of the body and attack the centre of the body," an early form of centre-line theory in fact.

Motobu also made full use of the lead hand for striking. This was rather advanced for that time, when the orthodox method was to block using the forward hand and to counterattack using the rear hand. Motobu taught that the forward hand, being closer to the opponent was quicker in action and should be used for striking effectively.

Choki Motobu relied mainly on hand techniques, with the feet and knees being used in a supporting -- but effective -- role, aiming his kicks at the stomach, groin and knee joints. He often liked to grab and he also used basic techniques of covering or checking the opponent's hands and arms. His attacks were directed not only to the face and midsection, but also to the groin (striking with the knee or foot, or grabbing the testicles) and knees (with stamping kicks). The forefist, backfist, elbow, and one-knuckle fist seem to have been his favourite weapons. According to Shosin Nagamine, Motobu attached some importance to the one-knuckle fist (keikoken), and he would train this technique on the makiwara, striking with full force. Over the years he had found that at close quarters the orthodox forefist punch might be smothered or unable to generate sufficient power and that in such situations keikoken could be very effective. "No other karateman in the history of Okinawan karate," wrote Nagamine, "has ever matched Motobu in the destructive power of keikoken."

As for training equipment, Motobu stressed the use of makiwara, and also recommended the use of the chishi and sashi, the traditional tools for building the strength of hands and arms. He also used to practice a crude form of weight lifting, lifting a heavy stone weighing say 130 lbs., to his shoulders daily.

Motobu sensei was actually the first of the Okinawan karate masters to settle in Japan, preceding Gichin Funakoshi by a year or so. He came to Osaka in 1921, but his purpose in coming to Japan may not have been to teach karate. He may simply have moved because, like many Okinawans, he believed Japan offered greater opportunities to make a living. In 1879 the Ryukyu Islands were made a prefecture (Ken) of Japan, and from then till 1945 this Okinawa-ken was Japan's poorest and most neglected prefecture. [EN6] Consequently, many islanders emigrated to Japan and it was estimated that by 1940 over 80,000 Okinawans were living there. This was out of an Okinawan population of something over half a million.

Motobu had been living in Japan a couple of years when he made the acquaintance of a judo teacher named Doi, who encouraged him to try and teach karate in Japan. Motobu subsequently began giving demonstrations and teaching in the Kobe-Osaka area, but development of the art was slow. After a couple of years he thought of giving it all up, but then in the mid-1920s interest in the art slowly began to grow. In 1927 he moved to Tokyo where he probably saw greater potential. [EN7]

When Motobu came up to Tokyo, Gichin Funakoshi had already been teaching there for several years, and a certain amount of ill-feeling arose between the two men, who had known each other back in Okinawa. It was something like a question of who was to assume the leadership of karate in Japan, but really, the two men were incompatible personalities. Gichin Funakoshi for instance seemed to feel that Motobu did not really understand the true nature of karate. Funakoshi, a man who valued propriety and culture, criticised Motobu's lack of education -- he called him an illiterate -- and his rough behaviour. For his part, Choki Motobu said that Funakoshi's art was just imitation karate, not much more than a dance. A Japanese karate teacher named Fujiwara has also pointed out that in the rigid social ranking system of Okinawa, Choki Motobu was two classes higher than Gichin Funakoshi was and so it was impossible for him to regard Funakoshi as his superior in any way.

I don't know if much ever came of all this, but there were rumours. Yasuhiro Konishi, who studied with both masters, heard that one time when the two men met, they began comparing techniques of attack and defence, as Okinawans often do. In demonstrating a movement Funakoshi was unable to block Motobu's thrust completely and moreover was knocked back several feet by its force. Konishi heard that Funakoshi was resentful about this. There was also a rumour that Motobu had challenged Funakoshi to a match and when the two met, he swept Funakoshi to the floor and followed up with a punch to the face, which stopped a couple of inches short -- just to show who was boss, I guess. Konishi could not vouch for the truth of this, and it may never have happened. Reading all the available material on Gichin Funakoshi, he does not come over as the type of person who went in for challenge matches -- just the opposite in fact. However, if the two men ever had met in a serious contest then (this is just my opinion) Motobu would probably have won rather easily. For one thing, Funakoshi, who was only 5 foot tall, was slightly built and would have been heavily outweighed. For another, Funakoshi never became involved in fights, whereas Motobu had the experience of numerous street fights behind him and was a fighter by nature.

But anyway, the years rolled by and "the leadership of karate", if it could be called such a thing, did pass to the Funakoshi school. The Motobu method does not seem to exist today as a distinctive style. Funakoshi organised his teaching well, he had energetic helpers (including his brilliant son, Yoshitaka), and influential friends such as Jigoro Kano, the famous founder of judo. Funakoshi's first book Ryukyu Kempo Karate (1922) contained forewords by such people as Marquis Hisamasa (the former governor of Okinawa), Vice Admiral Chosei Ogasawara, Count Shimpei Goto, and so on. Choki Motobu, however, never sought out such patrons, and in fact, according to Hironori Ohtsuka he was quite a solitary man. This agrees with the view of Konishi, who was quite close to Motobu for several years and never once saw him in an actual fight. Konishi felt that, although Motobu was obviously an exceptional fighter, he would never provoke trouble and was actually a very quiet person. So it sounds as if Choki Motobu grew calmer as he grew older. He seems to have been a straightforward, intelligent, but uncomplicated type of person who lacked Gichin Funakoshi's education and knowledge of Japanese culture and etiquette. Motobu did not speak mainland Japanese very well -- the Okinawans had their own dialect which was often incomprehensible to the Japanese -- and even when he moved to Tokyo he had to use Yasuhiro Konishi as an interpreter.

Choki Motobu spent nineteen years in Japan,

teaching karate for most of that time. In 1940 he returned to Okinawa and

died there in 1944.

"When Human Bullets Clash: Great Contest Between Karate and Boxing"

The story of Choki Motobu's contest with the boxer was featured in the Japanese magazine Kingu (King), in the September 1925 issue (No. 9), pages 195-204. It needed quite a bit of detective work to track this down and I must thank Mr. R.A. Scoales of the Japan Society of London and Mr. Kenneth Gardiner of the British Library for their help. It was Mr. Gardiner who finally located a copy of the article for me. I am also deeply grateful to Kenji Tokitsu, an authority on Japanese karate history now living in Europe, who made the following translation of the article.

***

During the action someone with the appearance of an old countryman went over to the organisers and asked if a late entry to the fighting would be allowed. The following conversation occurred.

"Mmm. Who is it you wish to enter?"

"Myself."

"What? You? Are you a judoka, then, or a boxer?"

"No."

"Well, what have you trained in then?"

"Nothing special. But I think I could manage this type of contest. So, will you let me enter?"

"Yes, let him enter!" cried the onlookers who had been following all this with interest. "Everybody would want to see a surprise entrant."

"But he says that he doesn't do judo or boxing. I wonder if he does some form of provincial wrestling."

"It doesn't matter. Since he wants to enter he must have learned something. If not, he's an idiot. Let him enter!"

"Well, okay," said the promoter. "Do you know the rules?"

"Rules?" replied Motobu. "What rules?"

"It's forbidden [for anyone but the boxer] to strike with the fists and feet." [The boxer meanwhile could not grab or throw.]

"Mmm. What about an attack with the open hand?"

"That's alright."

"Fine, let's get on with it."

"Wait a minute. What uniform are you going to wear?"

"I'll just wear my ordinary clothes."

"Those you're wearing now? You can't do that. I'll lend you a judogi."

The promoter brought a judogi, and looked at the man, still trying to make him out. As he stripped a murmur of surprise arose from the onlookers. Although his face was that of a man well over fifty, the muscular development of his arms and shoulders was impressive and his hips and thighs looked extremely powerful.

Motobu was asked who he wanted to fight, a boxer or judoka. He replied, "Whomever you like," and the organisers decided to send him in against a boxer named George. [No surname or nationality is given in the article. The name may be invented.]

As the contestants entered the arena a cry rose from the crowd. "Look! A surprise entry!" "Who is this Motobu? I've never heard of him." "He looks like an old man. What's someone like him entering a contest like this for?"

The contrast between the two men was striking. Here was a boxer seemingly brimming with vitality against a man of fifty who stood only 5 feet 3 or 4 inches. As they began, George took up a boxing guard and moved about looking for an opening. Motobu lowered his hips, raising his left hand high with his right hand close to his right cheek. The spectators thought this looked like some kind of sword dance (karate was more or less unknown in Japan at this time) but actually it was the opening position of the Pinan Yodan kata.

George, the expert boxer, seemed surprised by the ability of the opponent whose guard presented no weak spot. He contented himself with searching for an opening, continually moving his fists around and feinting. Motobu kept his position.

George's breathing grew less steady and, realising that he might tire himself out if things continued like this, he edged forward and sent out a fusillade of blows to the face. Everyone expected to see the end of Motobu but without moving his position he parried the blows with his open hands and forced his opponent back.

Growing more and more frustrated as the fight went on, George steeled himself for an all out attack. He drew back his right hand and threw a punch with all his strength at Choki Motobu's head.

Just at the moment when it seemed as if Motobu's face would be crushed he warded off the punch with his left hand. The force of the parry unbalanced the boxer, forcing his hips to rise, and at that instant Motobu struck him in the face with the palm of his hand. George, struck on the vital point just below the nose with the rising palm strike fell to the ground like a block of wood.

Everyone was shouting! What had happened?

The organisers went to look for someone to help George, who was still unconscious. "What a formidable character!"

Various people who went to talk to Motobu were astonished by his hands, callused and almost as hard as stone. Even a blow with the open hand would be terrible, they thought.

"Ryukyu karate," said one. "Hmm. I didn't know such an art even existed. In fact, you have such trained hands that you don't need to be armed. The hands themselves are terrible weapons."

Spectators and contestants continued to talk for hours about the events which had taken place.

A few observations on this old article might be worthwhile. As I said, when I first heard about it I thought it might give an accurate account of the contest, but although it obviously relates to the events which occurred, both the descriptions of the action and the dialogue are imaginative. The author, someone writing under the pseudonym Meigenro Shujin, does not give his sources but he had done some basic research and probably had talked to some of the spectators or even Motobu himself. He may have even been at the event, but somehow I get the impression that he was not an eyewitness. In any case the article appeared four years after the events described (if the date of 1921 is correct) and by then people's memories may not have been too clear about what actually happened.

One point of interest is that the artist who did the accompanying illustrations (K. Nabashima) confused the two karate masters teaching in Japan at that time -- Choki Motobu and Gichin Funakoshi -- and drew the illustrations as if it had been Funakoshi and not Motobu who had defeated the boxer. I wonder what Choki Motobu thought about that when he saw the article?

For other source material the artist and author must have used Gichin Funakoshi's Rentan Goshin Karate Jutsu, published the same year (1925), as the illustration for "the guard of Pinan Yodan" is copied directly from that book. Of course the posture shown is not an "on guard" stance but an intermediate position of defence before a counterattack is launched. The writer probably chose this stance because it looked very "karateish", but it is hardly conceivable that Choki Motobu would use it. Kenji Tokitsu has pointed out it is unlikely that Motobu knew the Pinan kata, and even if he did know the order of the movements he did not practice them sufficiently to apply the techniques in combat. Anyway, we know that Motobu's fighting stance was much more natural and orthodox than this. One point that does emerge from the story however is that Motobu fought without the use of gloves and struck the knockout blow with his bare hands -- whether with the palm or closed fist we can't really be sure. It does not seem that Motobu used palm strikes much at other times.

The nationality of the boxer is not given but there is a tradition that he was German or Russian. His identity will probably never be known, and even if it was, it probably wouldn't mean very much to us. He was probably a White Russian who found himself in Japan and was making some money knocking over judomen. That he was the German heavyweight champion on his way to the USA to fight for the world championship, as has been suggested, is extremely unlikely. There simply was no German contender for the title at that time. The top European heavyweight was the Frenchman Georges Carpentier who did fight for the world title in July 1921 and was stopped by Jack Dempsey in four rounds. The first German boxer to acquire international reputation was Max Schmeling but he didn't win the German title until 1928, when he beat Franz Diener. [EN8]

As for him being the "Russian Heavyweight Boxing Champion" (per Bruce Haines in his Karate's History and Traditions), the Russians did not even have an organized boxing movement until after the Second World War, when they began competing internationally in all sports. [EN9]

All this is not to put down Choki Motobu's achievement, but just to try and introduce some kind of perspective into the stories which have grown up about this contest. I think that, sitting there watching the action, Motobu must have realised he had the measure of the boxers, but it still took courage and confidence to step up in front of a skeptical crowd and accept the challenge. When the fight actually began, he did what had to be done -- and he did it at an age -- fifty -- when most people today are happy to spend their time in front of the television or down at the pub. What a fascinating character he must have been.

Just a few words too about Kingu magazine and its publisher, Seiji Noma, the founder of Kodansha. The magazine was launched in 1925 and its circulation soon passed a million. It was the largest circulation general interest magazine of the time and martial arts featured frequently in its pages, mainly judo, kendo and samurai tales. Apart from the Motobu story, karate was rarely, if ever, featured in its pages.

In his younger days, Seiji Noma had been a teacher and in the years 1904 to 1908 he was an instructor in Japanese and Chinese classics at the Prefectural Middle School in Okinawa, the Ryukyu Islands. He wrote in his biography The Nine Magazines of Kodansha (1934) that "there could scarcely be a more remote outpost than Okinawa," and like most home-island Japanese he regarded the Okinawans as little more than peasants. However, he liked them a great deal and believed that this period was, "in a sense, the time of my life."

What is interesting, though, is that Noma mentions karate (called tekobushi) in his book, in what is one of the very first references to the art published in English. He writes:

Some related matters

The Motobu family had its own martial art, which had been handed down through several generations. In the last century Chomura Motobu headed the family and he taught the system to his eldest son Choyu (1865-1927). The two other sons, Chosin and Choki, however, were not taught the art. As mentioned earlier it was customary for education to be centred on the eldest son, but Choyu Motobu himself also refused to teach his younger brother Choki because of the latter's rough behaviour. That is the story anyway.

An Okinawan named Seikichi Uehara was taught the art, though. He later began teaching and in 1961 formed his own school, calling it Motobu-ryu. Motobu-ryu is not to be confused with Choki Motobu's karate, and in fact it is not even a karate system. It is closer to jujutsu or aikijutsu, concentrating on locking and throwing techniques.

During Choki Motobu's period in Japan he taught such Japanese as Yasuhiro Konishi, Tatsuo Yamada, H. Ninomiya, S. Uejima (Kushin-ryu) and Hironori Ohtsuka (Wado Ryu). He also taught such Okinawans as Chozo Nakama and Shoshin Nagamine, and his influence can occasionally be seen in the teachings of these masters.

Yasuhiro Konishi, who died a couple of years ago, was one of our last links with the heroic period of Japanese karate. (A feature on Konishi, plus an exclusive interview, appeared in Fighting Arts, Vol. 4, No. 6.) It seems that Konishi knew anybody who was anybody in the martial arts. He originally practiced jujutsu and kendo but then in 1923, met Funakoshi and his assistant, Hironori Ohtsuka, and began studying karate. He was also a friend of Kenwa Mabuni, the founder of Shito-ryu, and one of the first students of Choki Motobu when Motobu settled in Tokyo. Konishi also trained with aikido's founder, Morihei Ueshiba, and he believed that, of all the experts he had trained with, Ueshiba was the greatest, a true master.

When Konishi left Funakoshi's school and began to study karate with Motobu, Funakoshi regarded him as a heretic. Motobu was so poor at this time that he was thinking of returning to Okinawa but Konishi helped him out by organising a kind of support association.

The bad feeling must have died down within a few years because Funakoshi was grateful when Konishi helped him enter the illustrious martial arts association, the Butokukai. Funakoshi was given the grade of Renshi, and later Tashi, and it is ironic that Konishi was on the Butokukai's karate examining board, since of course he was actually Funakoshi's student.

Konishi remembered the original group of Motobu's karate students in Tokyo. It included such people as Seiko Fujita, a jujutsu and martial arts expert who is remembered in some quarters as the "last officially recognised ninja" (i.e., the last to see active service), Lion Kamemitsu, and Tsuneo "Piston" Horiguchi, a western boxer -- and a colourful group it must have been.

In a little Japanese-language book called Talks on Karate, Konishi also reminisced with Hoshu Ikeda about Tatsuo Yamada, one of the earliest of Motobu's Japanese students. Yamada later founded "Nippon Kempo Karate" and I think he experimented quite a lot with bogu kumite (sparring with protective equipment). He was a tough, uncompromising character -- Konishi seemed to think he was something like "a boss of gangsters" -- and he called other karateka "dancers." Yamada was a friend of Hironori Ohtsuka and stayed with Ohtsuka during one period. Every time Ohtsuka went out to do a demonstration of kata, Yamada would say something like, "Oh, you're going out to dance again." Ikeda and Konishi agreed that Yamada was interested in a kind of precursor of kickboxing. Konishi told Ikeda that at that time (the 1930s) Tatsuo Yamada was one of the karate radicals. ("You can say that again!" Ikeda responded.)

Incidentally, Yamada was also an early student of Gichin Funakoshi, and Mas Oyama once said that he was the best karateman Funakoshi produced. This is not a view that many people would take, but Oyama may have seen in Yamada an early version of himself -- someone who stressed realism, conditioning and hard kumite; a radical who did not blindly follow tradition.

Piston Horiguchi was referred to earlier in this article, when his sparring match with Choki Motobu was mentioned. In fact, during his classes, Motobu would often tell Horiguchi to get up and spar with him.

A western-style boxer was something of a rarity in Japan in those days. [EN10] A fighter would frequently have to give away weight, and as an attraction boxers were occasionally known to fight sumo wrestlers. (They were not the grand champions, but still…) Not surprisingly their careers were short.

But what fighting spirit they had! Japanese boxers today are known for their courage, but the few veterans who can remember the pre-war days say that the modern fighters are soft by comparison -- although admitting that the modern fighters are better athletes and much better boxers.

Credits

Information on Choki Motobu and the other early masters of karate is scattered and difficult to trace. I am grateful to the following for their invaluable help: K. Gardiner, R.A. Scoales, and Kenji Tokitsu for help with the old "King" article; Mr. and Mrs. Brian Waites and Ron Ship for translations or help with translations; and Henri Plée and Terry O'Neill for material from their collections. Photos are courtesy Graham Nobel.

Editor's Notes (hit your back button to return to the text)

EN1. The first known Japanese-language karate book was Gichen Funakoshi's Ryukyu Kempo Karate (1922). In Ryukyu: A Bibliographic Guide to Okinawan Studies (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1963), Shunzo Sakamaki wrote that Karate Goshin Jutsu (1917) and Karate Goshin Hijutsu (1921) by Myuoken Kensai were earlier. However, this is not accurate, as the two earlier books described a jujutsu-based system of empty-handed combat rather than an Okinawan variant of southern Shaolin. This was confirmed by the National Diet Library of Japan in a letter to Graham Noble, and visually verified by a visit to the stacks by Mitchell Ninomiya.

EN2. This is not to say that there might not be something in the Japanese sporting press of the period, but like early issues of The Ring and Police Gazette, such documents are collectors' items even in Japan.

EN3. During the 1920s, the yen was worth about US $.45, and in October 1925 a Japanese laborer earned about ¥2.15 per day while a Chinese earned ¥1.24 and a Korean earned ¥1.2. So, assuming Motobu was working as a security guard, this sum represented around two months' wages.

EN4. The 19-year old Tsuneo "Piston" Horiguchi started boxing in Tokyo during the winter of 1932-1933. As he weighed about 125 pounds, Horiguchi usually fought featherweight. (I say "usually" because Japanese promoters tended to match fighters by their ability to please the crowd rather than their actual weights.) During most of the 1930s he was considered the Japanese national champion, but based on his international results the highest he was ever ranked internationally was third best in Hawaii. For further information, see Joseph R. Svinth, "Tsuneo 'Piston' Horiguchi," on this site.

EN5. It is possible that the contest was actually in Ryukyuan sumo (tegumi) rather than karate. For the discussion, see Joseph R. Svinth, "YABU Kentsu, 1866-1937: Karate Pioneer," Journal of Asian Martial Arts, forthcoming.

EN6. Okinawa's financial backwardness relative to the rest of Japan continues to the present.

EN7. The influence of judo founder Jigoro Kano on the spread of karate must not be underestimated. In 1922, he personally encouraged Gichin Funakoshi, and in 1927 the kind words he had for Chojun Miyagi and Kenwa Mabuni helped convince those two teachers to introduce their karate styles into Japan. For details, see Gichin Funakoshi, Karate-do Kyohan, The Master Text, translated from the Japanese by Tsutomu Ohshima (Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1973), 11; Gichin Funakoshi, Karate-do Nyumon: The Master Introductory Text, translated from the Japanese by John Teramoto (Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1988), 26-27; and Graham Noble, "Master Funakoshi's Karate: The History & Development of the Empty Hand Art," Dragon Times, 4 (1995) 7-8.

EN8. Although German Americans such as Otto Flint, Rudi Uzhols, and Adam Ryan boxed professionally in the United States during the early 1900s, when English promoter Jack Slim tried introducing Queensberry rules boxing into Berlin around 1910, he found little interest in an activity most Germans associated with brawling. Then, during World War I the YMCA introduced German prisoners-of-war to the sport. After the war some German veterans continued boxing, and this led to the establishment of a Deutschen Reichsverband für Amateurboxen in 1919. Over the next several years, boxing clubs were established throughout Germany and Austria, and by 1921, members of the German right wing were claiming that boxing and similar combative sports provided the "moral antidote needed to save German youth from further moral ruin now that the [mandatory] military service has been abandoned."

EN9. At an international level, this statement is correct, but during 1922-1923 the Bolsheviks introduced boxing as a mass sporting movement into the Soviet Union, and by 1934 the All-Union contests in Moscow were drawing about a hundred fighters. In Japan, the Russian boxers were mostly White Russians and Czechs who had been evacuated from Vladivostok in October 1922. Yujiro Watanabe, the father of Japanese professional boxing, fought several of these men and said that they were not real boxers, but instead men who had never seen gloves before coming to Japan. This was not hyperbole, either, as in The Ring in November 1924 Dan Walton described Ivan Karloff, a 25-year old White Russian who had started boxing in Yokohama during 1923. "A crack athlete in Russia, Karloff took up jiu jitsu and boxing while in Japan and his first boxing contest resulted in a four-round kayo victory over Jack Anson, a giant negro sailor." Technically, said Walton, Karloff "showed promise, although naturally his ring tactics were by no means polished."

EN10. Although there

had been boxing versus jujutsu matches in Japan as early as the 1890s,

the country's first gloved boxing match between recognised professionals

took place in Tokyo in May 1922. The Japanese participants included Yujiro

Watanabe and "Young Togo" Koriyama, both of whom had learned their trade

in the United States before 1920, while the American participants included

the California fighters Charley "Young Stanley Ketchell" Mitchell and Spider

Roche.