Copyright © Jonathan Wayne Riddle 2007. All rights reserved.

Ancient Egyptian Stick Fighting

Analysis and Reconstruction of the Sport

Written by Jonathan Wayne Riddle © 2003

Little Analysis has been done on Ancient Egyptian Stick Fighting. It has been addressed by authors in the study of sports history. The analysis has never been done by someone who has experience or expertise in fencing or stick fighting. Most of these books on Ancient Egyptian sports history cover a great deal on wrestling. There are more materials left by the ancient Egyptians on this subject, but even with limited information analysis can be done. Several assumptions have to be made those assumptions can be proven wrong with new evidence.

Origins of Ancient Egyptian Stick Fighting

The Egyptians, modern and ancient, were accomplished in stick fighting. In both modern and ancient times stick fighting has been a martial art. Stick fighting has at least some aspects of martial arts in them as well as ceremonial. Ancient Egyptians performed stick fighting as a tribute to the pharaoh. Stick fighting was also performed between Ancient Egyptian and Ancient Nubians as well. Stick fighting is common in the African culture and in the Middle Eastern culture. Stick fighting is found through out the region in different forms, with different systems of rules. One common element is that the game used to teach skills important to a warrior, such as speed, strength and courage. The ancient Egyptian trained for war. Just as with the Greeks they also had athletic games. They had several combat sports, such as boxing, wrestling, horsemanship, knife throwing, archery and stick fighting. The weapons and equipment that would have been seen on the battle field was the sword, a knife, or dagger, a hand axe and shield with some armor, such as helmet and greaves. The kopesh or Egyptian sickle-sword was commonly used. After studying different drawings, looking at the design and materials of the Kopesh, the Kopesh was not a thrust, but a cutting weapon. Bronze is not a very strong material and will bend when a lot of force is applied. The ideal or best target on the body would be the head and neck. Several drawings show the Pharaoh hold the head in place by the hair of the enemy. The kopesh held up high aiming for the neck or the head. The cutting action was more of a chopping motion and not a pushing or a drawing motion. Bronze does not hold an edge very well. The weight of the weapon could have been a factor.

1.

Factors involving the Limitations of the Study

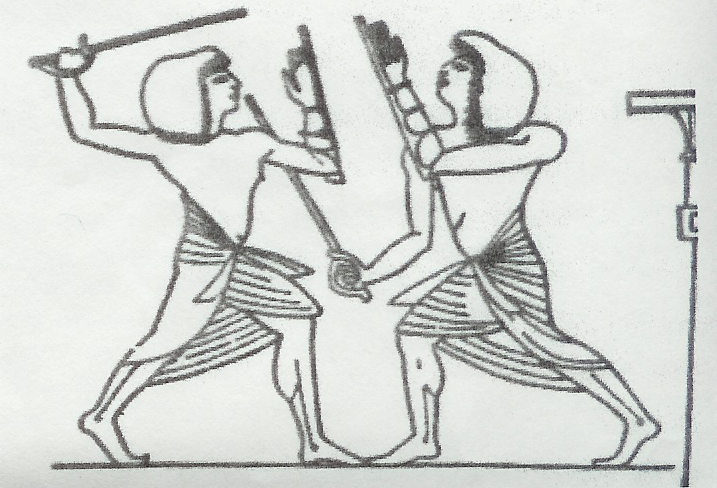

There are limitations on studying ancient Egyptian stick fighting, or stick fencing as some authors have called it. The limitations are do to the fact that there is no living tradition of the art and the study is limited to hieroglyphs. The amount of hieroglyphs which have stick fighting represented as a sport is very limited and gives only a small representation of the sport, however even with limited materials some details can be ascertained from observations of the drawings. The first question one has to produce is, are the drawings a true representation or an artist vision of what the combatants are actually doing? One conclusion that can be drawn about the combat sports of the ancient Egyptian is that the drawings, even with the limited dimensions, can give a good idea of structure as well as positions used in the martial art. From this information one can reconstruct the rules and the techniques in the use of the stick during performance.

2. Tomb of Merire II at El Amarna, c. 1350

Possible

Rules, Methods and Techniques used

3. Thebes, Egypt, c. 1350 B.C.E.

Modern Egyptian and African Stick Fighting

In modern Egypt stick fighting and stick dancing is called tahtib. Tahtib is stick fighting and stick dancing is performed during marriage ceremonies and is popular during Ramadan. The stick is symbolic of masculinity and a phallus. This is a male dance only. Although there are women who are performing the dance, they are dressed as men and they are dancing with other women. The dance with the women, is to be flirtatious and the stick is a general symbol of masculinity and is manipulated by the woman. The stick is about four feet in length and is called an Asa, Asaya, or Assaya or Nabboot (www.alliancemartialarts.com/tahtib.html). In parts of Africa many tribes perform stick fighting, among the Surma, the Donga is performed. The Donga is only practiced among the men. The sticks are six feet long and individually carved by the owner. The objective is to knock down the other competitor. No protection is worn, with the exception of body paint.

The ancient Nubians performed stick fighting as well. In one picture a figure waits, while two competitors wrestle. The stick fighter is holding the stick in two hands, and the height of the stick almost equal to the height of the figure of the fighter. The stick fighter is also wearing the same type of belt as the wrestlers.

The similarities between the Zulu and the ancient Egyptians is uncanny. With the Zulu a blocking stick is used. Some of the stances used by the Zulu are similar to the drawings of the hieroglyphics.

Conclusion

Ancient Egyptian Stick fighting was probably based on actual fighting systems used in combat with a shield and a sword. It then probably evolved into a system with its own rules and methods. Several assumptions had to be made in order to understand stick fighting of the ancient Egyptians. The rules used by the ancient Egyptians were probably simple and few. There are two conclusions; either the contest was of endurance or of skill. There is stronger evidence that the game, is a game of skill and that hitting the head was goal. There were advantages of teaching stick fighting, along with other combat sports such as wrestling. The main advantage is the fact that the Egyptian army could be kept trained and ready for war. Reconstruction of this system of stick fighting can be possible with some imagination and ingenuity. Reconstructing a system based on the head being the target would be easier and safer of the two possible systems are used. Development of equipment is not out of the range of most modern practitioners.

Illustrations:

Scott T. Caroll, Journal of Sport History, Vol 15, No. 2

Michael Poliakoff, 1987 Competitioin, Violence and Culture Combat Sports in the Ancient World, 26

Michael Poliakoff, 1987 Competition, Violence and Culture Combat Sports in the Ancient World, 64

Bibliography:

Carroll, Scott T., Journal of Sports History , Vol 15, No. 2 (1998)

Coetzee, Mariť-Heleen, “Zulu Stick Fighting: Socio-Historical Overview” (2002)

Gumede, Thabisile, “Zulu man’s mission to put stick fighting on the SA sports map” Sunday Times-South Africa (2002)

Poliakoff, Michael Competition, Violence, and Culture Combat Sports in the Ancient World Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 1987

Reardon, Christopher “Days and Nights in the Artist’s” ‘ Workshop ‘ Ford Foundation Report 2000

“Tahtib-Middle Eastern Stick Fighting” <http://www.alliancemartialarts.com/tahtib.html>