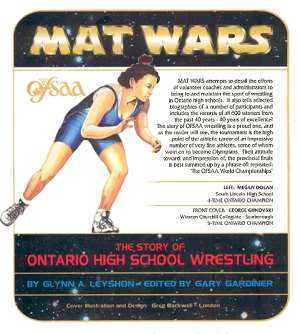

From Mat Wars: The Story of Ontario High School Wrestling,

by Glynn A. Leyshon and edited by Gary Gardiner (Gloucester, Ontario: CSFAC,

2000). Reprinted by permission of Glynn A. Leyshon. Copyright © 2000

Glynn A. Leyshon, all rights reserved.

-- Mike Payette, Canadian Wrestler, Winter 1991/Spring 1992

With those words Mike Payette, then technical director of the Canadian Amateur Wrestling Association (CAWA), launched the women's wrestling program in Canada. For once it was the national body leading the charge. Women's wrestling was already taking hold in some of the most unlikely countries. Japan, for example, had been sending women to the FILA (Fédération Internationale de Lutte Amateur, or international) world championships for females since the inaugural year of 1987.

The solution for the acceptance of female wrestling was simple -- have girls wrestle girls. [EN1] It was so simple, in fact, that no one had thought of it. There were legal battles looming in Saskatchewan, for example, because the Saskatchewan Amateur Wrestling Association was blocking the entry of females into the male competition. Once the female categories were added, the problems went away overnight.

"If you host it, they will come." That was the strategy that CAWA implemented to launch the program. After several successful exhibition events held at British Columbia's Simon Fraser University proved the viability of women's wrestling, CAWA then added a female division to the Canadian national championships starting in 1992. It would be up to the provinces to take up the challenge.

In Ontario, people such as Bill Smith in St. Catharines, Ralph Sneyd in Collingwood, and Frank Corning in Fergus welcomed the initiative. They had had girls involved in wrestling on an informal basis since the early 1970s and they also had witnessed some of the problems that mixed competition created. In the years that Harry Mancini was coaching at Bishop Ryan back in the 1980s he took his daughter, Melissa, to practice at the high school from about age five. And he entered her in meets competing against boys in age-group tournaments where because of her advanced technical skills and the fact that the male-female strength differential was not yet apparent, she, more often than not, won the weight class. [EN2] The problem was not when a girl lost, that was to be expected -- it was when she won! The young boys on the receiving end had no way to cope with a loss to the opposite sex, and teammates were less than sympathetic. In some cases the boys simply quit the sport in humiliation.

The Ontario Amateur Wrestling Association (OAWA) was also in favor of the CAWA initiative. Cognizant of the important role that Ontario Federation of Secondary School Associations (OFSAA) played as the spawning ground for their provincial teams, OAWA offered financial and administrative support for a separate female OFSAA division, when and if approval could be had. It was time to call the negotiator, Bill Smith. The male-led Sports Advisory Committee for Wrestling was very supportive of a girls' section and agreed that Bill should push ahead. He then approached the female-led Women's Competition Committee of OFSAA. There he was met with skepticism on two fronts. First, the idea of females grappling was culturally unacceptable -- girls don't fight. Secondly, there was the knowledge that all the coaches were male and some had less than impeccable reputations. It wasn't anything morally incorrect; it was just that their coaching antics were well known. Smith was low key, persuasive, and very patient. After about an hour and a half of negotiations he had a reluctant go-ahead to stage a small demonstration event at the 1993 championships. Girls' OFSAA wrestling had begun!

The first meet featured twelve girls in total. To ensure the host organizing committee would not be out of pocket for the inclusion of the girls' participation, the OAWA office provided the administration support, supplied the medals, and paid for the additional officiating cost. Invitations were sent to all district associations asking them to send up to two girls for the event. If some spots went unused then they would be offered to other districts that wanted to send a third girl. To ensure participation and to get the momentum going, Smith took it upon himself to contact those coaches whom he knew were currently coaching girls to advise them of the opportunity. The wrestling uniform was modified slightly because female singlets were not yet widely available. Most girls wore a boy's singlet over a T-shirt. There were no weight divisions. Once the girls arrived they were paired according to their actual weights and each girl wrestled two exhibition matches. The techniques demonstrated were basic and the conditioning was not always the best. However, there was enthusiasm and the girls were eager to compete.

"If you host it, they will come." About this time coaches with girl athletes on their school teams began looking for those few invitational tournaments that included a separate division for females. And tournament directors were learning that offering a female division added extra excitement, as well as revenues to the coffers. The number of girl participants was slowly increasing.

Acceptance that female wrestling was a good thing was also growing. However, there were those who still objected. Nowhere in OFSAA was there a female coach and at certain schools the male coaches refused to allow girls on their teams. Some referees even boycotted the girls' matches. But the seed was germinated and the traditional concept of wrestling as a male-only bastion was eroding.

Jim Dempsey, one of the die-hard oldsters, became one of the converted:

For the second OFSAA championship for girls held in 1994, the invitations were sent out along with the boys. There was some question at that time as to whether the girls required different or adapted rules. After some serious consideration by the OFSAA Advisory Committee it was decided unnecessary. Girls had been working out on the same practice mats as the boys for some time now and were often sparring with them, so why complicate things by implementing a different set of rules?

As was the case the year before, there were no predetermined weight classes. To encourage the widest participation possible there were also no restrictions on the number of girls who could enter. Smith was delighted when 56 girls, representing nineteen different schools, registered. As the makeshift divisions were created, Bill recorded the actual weights. The data would be used to establish norms for the eventual creation of weight classes. The girls were tenacious, technical proficiency was improving, and most importantly, more and more coaches were realizing that girls' wrestling was a viable sport. And it was here to stay.

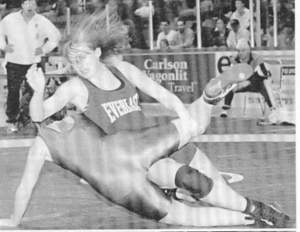

Action from the 2000 Ontario championships

In 1995, at the third OFSAA exhibition, the numbers had grown to 134 entrants representing some seventy schools. Based on Smith's scientific data, nine formal weight classes were introduced. That number would be adjusted to ten and then twelve in the subsequent two years.

Nineteen ninety-seven was a significant year for the advancement of girls' wrestling. The Women's Competition Committee, satisfied with the four invitational events staged thus far, agreed to designate girls' wrestling as a "festival," a term that indicates that a new sport is under consideration for full championship status under the aegis of OFSAA. Girl's wrestling was no longer just an exhibition, it was now a legitimate OFSAA event. This official status not only added prestige, but it was a positive factor when it came time for school administrators to approve the participation of their students.

By 1998, the girls' division was so successful that the number of entries broke 200. From a humble beginning of just twelve girls in total just five years earlier, there were now, on average, sixteen girls per weight division. And with the increased numbers of girls participating there was beginning to be a need for qualification meets to determine who would fill the two spots per weight class allocated to each district. As was the case with the boys, soon it would be a privilege just to wrestle at OFSAA.

Qualification standards had raised the bar. Girls trained harder than

before, fitness levels were approaching or on par with the boys, and the

technical level of the girls had made a quantum leap. Not surprising when

one realizes that the girls were sparring as equals with the boys, and

of course they were getting the benefits of thirty-plus years of coaching

expertise. They were starting at a higher level than were the Ontario boys

back in 1961, and it was all to the good.

Girls' wrestling seems solidly entrenched and once the event becomes a full championship event in 2001, it will have all the rights and privileges of any other OFSAA sport. In the meantime, Bill Smith, as one of the guardians of girls' wrestling, has gone to great lengths to ensure equality in all aspects -- girls and boys wrestle on the same mats, with the same rules, using the same referees, and their medals are presented in an identical fashion. It is unlikely that the numbers of girls will ever reach those enjoyed by the boys, but the tournament is certainly respectable, if not spectacular, in its present scope.

There is one more step in the evolution that is needed to bring the

sport of female wrestling full circle, and that is female coaches. Eventually,

as the girls that wrestle go on to university and graduate, hopefully some

will find a way to put back into the sport through coaching. As volunteers,

as Canadian wrestling coaches are, there is only so much time to go around

and with more and more girls turning out for wrestling, the current set

of coaches is being pushed to the limits. Without reinforcements in the

coaching ranks, the current growth of female wrestling cannot be sustained.

But it is a good problem to have.

About the Author

Glynn A. Leyshon is a former captain of the University of Western Ontario wrestling team, the former coach of Ontario's Winston Churchill collegiate wrestling team, a former Canadian Olympic wrestling coach, and the author of several books about Canadian wrestling and judo. This article is an excerpt from his latest book, Mat Wars: The Story of Ontario High School Wrestling. To order, contact Dr. Leyshon at Gley706030@aol.com. Cost, including postage, is CDN $20 anywhere in North America; outside North America, send US $20.

EN1. Since this is an article about high school student athletics, the terms "girls" and "boys" were preferred by both the author and the editor to the more politically correct but enormously precious "juvenile [gender] persons."

EN2. Although individuals vary enormously, the statistical

average adult female possesses 72% of the leg strength and 60% of the lower

back strength per inch of height as her male counterpart.